Snitches, Stings & Leaks: how Immigration Enforcement works

[responsivevoice_button]

The Byron Hamburgers “sting” was no one-off. This report, analysing leaked Home Office documents, shows how the 6,000 workplace raids a year rely on “low grade” public informing, employers collaborating to target workers, and Immigration Officers acting without legal warrants.

Summary

In July 2016 restaurant chain Byron Hamburgers caused an outcry after setting up a “sting operation” with Home Office Immigration Enforcement to arrest its own workers. But, as this report shows, this was no one-off. Such operations are part of standard practice in the Home Office’s campaign of around 6,000 workplace raids a year, which is routinely based on “low grade” public informing, employers reporting on workers, and Immigration Officers acting without legal warrants.

This report draws on leaked Home Office intelligence documents from 2014’s “Operation Centurion”, analysed here for the first time, alongside other public and confidential sources. Key points include:

- The bulk of initial intelligence comes from around 50,000 “allegations” per year from “members of the public”. Most tip-offs that actually lead to raids are classed as low grade “uncorroborated” information from “untested sources”.

- 12 times more men than women are arrested in workplace raids; people from Pakistan, Bangladesh and India make up 75% of those arrested. Restaurants and takeaways are the main types of businesses hit.

- Immigration Officers seek to follow up tip-offs by contacting employers and asking them to collaborate ahead of raids. This collaboration may include: handing over staff lists; handing over personal details including home addresses, which are then raided; helping arrange “arrests by appointment”, as in Byron’s case and also mentioned in the leaked “Operation Centurion” files.

- Besides Byron, high profile cases of employer-supported raids have included cleaning contractors Amey and ISS (working for SOAS university), and food delivery service Deliveroo in June 2016. In these three cases, raids occurred while companies were involved in disputes with workers and unions.

- In general, employers are not legally obliged to co-operate in these ways: they can give or withhold “consent”. However, in practice, businesses complain that Immigration Officers often do not give the impression that co-operation is voluntary.

- The main pressure for co-operation is not legal but financial. Businesses are liable for a civil penalty of up to £20,000 per illegal worker found – although only if it was “readily apparent” that workers had no “right to work”, e.g., their documents were obviously fake. But this can be reduced by £5,000 for general “co-operation”, plus another £5,000 for “reporting” workers.

- A December 2015 report by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration found that officers had warrants in only 43% of raids. In most cases, they claim that business managers grant “informed consent” to enter – but there is no documentation to support this.

- Officers also claim that they act with “consent” in routinely rounding up andquestioning people who are not named suspects. But the Chief Inspector found: “in the 184 files we sampled there was no record of anyone being ‘invited’ to answer ‘consensual questions’”.

A PDF version of this report is available to download.

Introduction

In July 2016 the posh fast food chain Byron Hamburgers caused an outcry after setting up a “sting operation” with the Home Office to trap its own workers. The workers were called in for workplace meetings, then arrested by “Immigration Enforcement” teams. As Byron was hit with pickets, boycott calls and an actual plague of locusts, mainstream and social media debated the morality and legality of its actions.[i]

But the Byron sting is no one-off. On the contrary, operations of this kind are part of the standard Home Office approach to “illegal working”. This report gives an overview and analysis of the Home Office’s campaign of workplace raids, and shows how it relies on a number of fundamental pillars:

- informing by “members of the public”: around 50,000 public tip-offs a year provide the bulk of initial intelligence;

- employer collaboration: operations standardly involve pressuring employers to help target workers by handing over staff lists, providing personal details which may lead to home raids, or indeed arranging “arrests by appointment” as in the Byron case – none of which are, in general, legal obligations of the employers;

- entry and interrogation without warrants: over 50% of raids are not sanctioned by court warrants; instead immigration officers can avoid scrutiny by claiming that businesses give so-called “consent” on the door.

This report makes use of a valuable source: leaked intelligence documents from the June 2014 “Operation Centurion”. This was a two-week nationwide campaign of immigration raids involving all local Immigration Enforcement teams. Things did not go according to plan: documents summarising Home Office intelligence on 214 workplace targets, from corner shops to major factories or warehouses, were leaked to the Anti Raids Network and others.[ii]i In some cases the intelligence was specific enough to get advance warning to workers in dozens of potential targets. This is the first time the leaked data have been analysed in any depth.[iii]

Reading the Operation Centurion files alongside other sources – including reports by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI), replies to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, and communication from members of the Anti Raids Network[iv] about their experiences and those of businesses and workers they are in touch with – we can get a good picture of the system as whole. We can see how it is based on informing, employer collaboration, and intimidation of both bosses and workers during raids in ways that go well beyond the Home Office’s official guidance – or indeed, in some cases, the law.

We can also see that, as senior Home Office managers are themselves well aware, this system of suspicion and intimidation has no actual hope of “ending illegal working”. But it works very well at creating a climate of fear and division, which serves politicians to mobilise racist panic and employers to exploit workers.

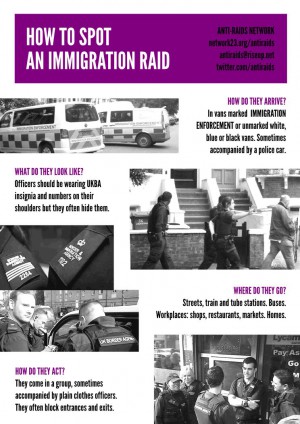

1. “Immigration Enforcement” – the basics

In the UK, border and migration control is overseen by one government ministry, the Home Office. Its internal workings went through restructuring in 2012-13 in which the old “UK Border Agency” (UKBA) was abolished and replaced by three “directorates”. These are: Border Force (BF), which deals with external frontiers; UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI), which deals with legal migration routes including issuing visas; and Immigration Enforcement (IE), which polices migrants within the territory.

Immigration Enforcement itself has different sub-sections. Our main focus will be on the 19 local Immigration Compliance and Enforcement (ICE) teams. These are the troopers on the ground, the Immigration Officers (IOs) and Assistant Immigration Officers (AIOs) who actually carry out the raids.[v]

We will also encounter the local Operational Intelligence Teams (OIUs) that work with them, and their Field Intelligence Officers (FIOs). These intel officers are technically part of the Immigration Intelligence (II) division, which also includes strategic intelligence teams at national and regional levels.[vi] Also relevant are the Crime and Financial Investigation teams (CFIs), which deal with more serious immigration-related crimes such as forging passports or forced human trafficking;[vii] and the Civil Penalty Compliance Team (CPCT), which issues financial penalties to employers found breaking immigration rules.

The ICE teams carry out various kinds of operations, e.g., breaking up “sham marriages”; raiding “Houses of Multiple Occupation”; or tracking down and arresting individual asylum seekers, people who have “overstayed” their visas, and other individuals identified as targets to be detained and deported. They have also run high visibility “street stop” operations questioning passers-by on busy streets or outside stations; street-based “crime reduction operations” (CROPs) targeting neighbourhoods alongside police; or, e.g., operations on public transport in collaboration with ticket inspections.

However, street immigration enforcement operations appear to have decreased in the last few years. One reason may be that they provoke public outcry and resistance being blatant cases of “fishing expeditions” based on racial profiling. Like the police and other law enforcement agencies, Immigration Enforcement aims to present itself as “intelligence led”.[viii]i It claims that its operations target named individual “immigration offenders” previously identified by specific intelligence. This is clearly not the case with street stops, nor in many workplace raids either, as we will see.

Currently, “illegal working” operations are a mainstay of IE activity.[ix] However, we might expect to see some new kinds of operations in the future, as immigration controls extend into ever broader areas of everyday life. For example, the new “Right to Rent” introduced in the 2014 Immigration Act requires landlords to check documents of prospective tenants. It could be that this will lead to an increase on residential raids – e.g., with ICE teams sourcing “illegal renters’” details from letting agents in the same way they approach recruitment agencies for “illegal workers’” home addresses.

Our focus in this report is on workplace raids. These vary from routine corner-shop busts to major operations against big factories or multiple premises, possibly involving a number of ICE teams and also other state agencies. The Home Office classifies operations into “upper, middle or lower tier”, depending on “the number of offenders, suspected criminality and/or politically sensitive issues”.[x]

Some basic figures on workplace raids

Before looking at the leaked Operation Centurion documents, we can get a useful overall snapshot from a December 2015 ICIBI report on “An Inspection of How the Home Office Tackles Illegal Working” (hereafter, Illegal Working 2015).[xi] According to this, the Home Office carried out a total of 36,381 “illegal working” “visits” across the UK between 2009 and 2014, or roughly 6,000 a year. In just the first nine months of 2014, for example, there were 5,414 “visits”.[xii]i From the 36,381 visits, there were 29,113 arrests. More than two thirds of visits (24,621, or 68%) don’t lead to any “illegal workers identified” or arrested, but clearly others end with multiple arrests.

Some obvious facts stand out about who is arrested. First, the large majority are male: in fact twelve times more men than women were arrested between September 2012 and January 2014. Secondly, the biggest targets by far are people from South Asia. 75% of all people arrested in that period were from Bangladesh, Pakistan or India, in that order. The top ten nationalities, in full, were: Bangladesh 27%, Pakistan 27%, India 21%, China 10%, Nigeria 3%, Afghanistan 3%, Sri Lanka 3%, Nepal 2%, Vietnam 2%, Albania 2%.

This breakdown of nationalities appears to be related not just to the history of British colonialism, but to the types of businesses that offer easy targets. The ICIBI report sampled 184 visit files, with 179 arrests. “One hundred and seven of the 184 premises visited were high street restaurants and/or takeaways, mostly Indian Subcontinent or Chinese cuisine, with some fried chicken outlets.”

A Freedom Of Information request to which the Home Office replied in 2013 (after appeal) also confirms that “restaurants and takeaways” are primary targets. In 2011 there were 2,591 visits to these businesses, leading to 1,939 arrests; in 2012 there were 2,514 visits, with 2,320 arrests. Comparing these figures with the ICIBI report, in both years 47% of all raids were to “restaurants and takeways”.[xiii]i

The leaked Operation Centurion documents confirm some of the same basic patterns. Nationalities are mentioned in 45 of the 214 targets listed. Nine of these mention people from Bangladesh, seven mention Indians – there are also two mentions of “Sikhs”, six mention Pakistanis, five Nigerians, three Vietnamese (all nail bars), three Albanians. There are also three references to Brazilians, one to a Chinese-owned business, one to Ukrainians, one to Mauritians, one to “Africans” in general, and one to Eritreans – who are described as “not the best nationality for us” (presumably because it is legally difficult to deport people to the Eritrean dictatorship) “but a new sector nonetheless.”

However, there is also a notable difference in the Op Centurion files: only 11 out of the 214 Centurion targets are restaurants. The top five sectors are construction (29), retail (20), leisure or entertainment (18), care homes (14), and manufacturing, i.e., factories and “sweatshops” (14). Then come restaurants (11), transport (11), garages (10), recruitment agencies (10), hotels (9), offices or “white collar” (9), beauty (8), security (7), food production and packaging (6), cleaning (5), markets (4), agriculture (2), logistics (1), and a charity (1). Several other intel items feature various sectors, or are not really workplace raids at all but, e.g., target rough-sleepers (1), or an individual’s home (1).

Why are the two samples so different on this point? Perhaps, to speculate, as Operation Centurion was intended to be a “showcase” and media spectacle for Immigration Enforcement, teams were instructed to get away from the usual routine of busting the local takeaways and present a more varied range of ops. The ICIBI report suggests that Home Office bosses don’t see the obsession with Asian restaurants as ideal: “some ICE managers told us that more attention should be paid to other sectors.”[xiv] The Home Office response to the inspection report stated that officials had “identified a number of new employment sectors” and were “diversifying the range of our enforcement work”.[xv]

One last summary statistic, this time relating to the immigration status of the arrested people – i.e., what they had “done wrong”. In the ICIBI sample, 45% were “overstayers”, i.e., people who arrived in the UK on a valid visa but then stayed after it had run out; 20% were “illegal entrants”; 13% were “working in breach” of their visa conditions: e.g., people on student visas working full time.

The immigration enforcement process: from tip-off to raid

In the rest of this report we will focus on three key issues, which relate to different stages of the planning and operation of immigration raids. To put these in context, we will first sketch an overview of the raid process as whole. Another ICIBI inspection report, from 2014, outlines how it is supposed to go, in seven stages:

- The process is supposed to begin with an “allegation or other information regarding illegal working received by the Home Office”. This is the stage we will look at in Section 2, asking: where do these “allegations” come from?

- The initial lead should then be “researched and enriched” by intelligence officers, including the “Field Intelligence Officers” (FIOs) who may hit the streets to check out businesses. In Section 3, we will see how this intelligence stage often involves approaching employers, and perhaps putting pressure on them to collaborate in targeting workers in different ways.

- The intelligence officers then present an “intelligence package” detailing the case to the local team’s “Tasking and Coordination Group” (TCG). It is this meeting that decides whether or not to go ahead with a raid.

- The Tasking Group schedules the operation and assigns it to a lead “Officer in Charge” (OIC).

- The OIC draws up a plan for the operation. This is meant to include a plan for how and on what legal basis to enter the target premises – the issue we will look at in Section 4. The plan may also involve ICE officers in plainclothes carrying out a “recce” of the site ahead of the actual raid, identifying entry and exit points and other relevant information.[xvi]

- The team should now go to a magistrate’s court for a warrant to raid the premises, or alternatively apply for an “Assistant Director’s letter” (see Section 4). As we will see, this stage is very often skipped or carried out improperly.

- The operation is conducted. During the raid, Immigration Officers are meant to search for, interview and potentially arrest people on whom they already have specific intelligence. They may also legally question other people who arouse “suspicion”, under specific circumstances, and if these people consent to being questioned. In practice, as we will see in Section 4, this is not what happens. As the Chief Inspector notes: “The files showed that officers typically gathered everyone on the premises together, regardless of the information known or people’s actions.”

Of course, for many people involved, the raid is not the end of the process but just the beginning.

According to the general IE statistics for 2009-2014, half of all the people arrested in those five years (14,493, so 50%) were eventually “removed” from the country. Many of those, in the process, spent weeks or months languishing in immigration detention centres. The majority were forcibly deported, handcuffed and “escorted” by private security guards. Though some were allowed to “voluntarily remove” themselves, i.e., take themselves to the airport – an outcome the Home Office is keen to increase as it saves a lot of money.

As for the employers, there is the chance of a criminal charge, but the most common outcome is a civil penalty of up to £20,000 per worker (see Section 2 for details). However, the Home Office’s record in actually collecting these fines is underwhelming: “the most recent figures showed that around 31% of debt raised was recovered and that it took an average of 28.4 months to recover it.” In a bid to improve its returns, the Home Office has contracted two private debt collection firms.[xvii]i

2. Allegations: where does “intelligence” come from?

Debates around immigration raids have sometimes focused on the issue of “racial profiling” vs. so-called “intelligence led” operations. In the wake of the Operation Centurion leak, Labour politician Keith Vaz, as chair of the House of Commons Home Affairs committee, appeared on TV to condemn the way raids appeared to be “fishing expeditions” for particular national groups, rather than being truly “intelligence led”.[xviii]i And yet there certainly is “intelligence” behind the raids. The Operation Centurion files give a very handy glimpse into how Immigration Enforcement gathers and processes “information flows”, and so finds its victims.

An obvious but key point: there is no way ICE teams can possibly hope to “visit” every business where “illegal workers” might be found. They carry out about 6,000 workforce “visits” a year, ultimately just a tiny sample. But this sample is certainly not selected at random. Managers may hope to direct their teams to targets which will “bag” big arrests. Or maybe, teams will prioritise easy options, like high street restaurants, which don’t need any careful reconnaissance or preparation. Even in this case, though, teams may not just strike the first restaurant they come to, but be led by a a more specific allegation – that is, a tip-off, someone grassing someone up.

In theory, all allegations received by Immigration Enforcement are processed onto a central computer system called the Information Management System (IMS).[xix] A new ICIBI inspection report on “The Intelligence Functions of Border Force and Immigration Enforcement”, published in July 2016, gives us a first glimpse of the nature of these tip-offs. In the twelve months between August 2014 and July 2015, a total of 74,617 allegations were entered on the system. 49,109 came from “the public” – e.g., calls to the Immigration Enforcement hotline, or electronically via a form on the Gov.uk website, or maybe in person to officers. Another 7,540 tip-offs were forwarded from Crimestoppers. 17,818 pieces of information were referred by “other Government departments”. Finally, 150 tip-offs came from MPs – presumably passing on information from constituents.[xx]

On this basis, it looks like the intelligence that “leads” Immigration Enforcement largely consists of snitching from “members of the public”, such as anonymous phone calls or web form entries. However, we need to dig further into a couple of points. First, how much use does Immigration Enforcement make of these public tip-offs? Many are likely to be “low grade” to say the least, and it could be that Intelligence Officers use them sparingly and selectively, filtering out only the most solid intel, or preferring information passed on by the police and other agencies. Second, these figures don’t tell us what proportion of operations come from information first uncovered by IE intelligence officers acting on their own initiative, rather than responding to allegations at all.

The Op Centurion files gives a few hints here. In the leaked documents, 30 entries offer some clue as to where the initial lead on a target came from. Eight mention “allegations”. For example, one entry notes an “allegation of 30 illegally working students” at a cleaning company; in an import company an “allegation has been received that they are employing persons illegally”; a manufacturing company is “alleged to be employing BRA nationals”; in a “middle tier” target “in addition to the allegations of illegal working, there are suggestions of document abuse”.

Another seven cases are referrals from other agencies. Three are from the police. After a worker contacts the police saying they have been trafficked and forced to work at a meat-packing plant, the police contact IE requesting involvement in a joint operation. In Glasgow, an “Immigration offender [is] encountered by police at Possible House of Multiple Occupancy […] Others possibly residing there.” Elsewhere, police propose a joint op also involving trading standards “during a series of test purchases at off licenses and pubs”. Two cases involve the Security Industry Authority (SIA), which licenses security guards. In one, the SIA passes on a lead on a large security company in Luton; in another, ICE are planning to actually “attend an SIA test and check status of candidates”.

Five cases are in fact repeat visits to old targets, including two to firms that haven’t paid old penalties, while another mentions “previous excellent results from enforcement visit”. Two other cases dig up unspecified “old intel”. In two cases, Immigration Enforcement has approached a company to provide information on its cleaning contractors, which then become targets.

If this sample is anything to go by, many ops do seem to start with some kind of tip-off. There is just one mention in the documents of a team “cold calling” to do speculative intelligence gathering, in this case around hotels in Wandsworth, South London. Although there is another reference to “markets being scoped/developed”, which might involve teams starting from scratch in a targeted area.

This picture is also supported by the ICIBI report on Illegal Working from December 2015. Here the inspector looks at a sample of 184 cases, which are evaluated according to the National Intelligence Model (NIM) “5x5x5” rating system – a standard model used by the police and other UK law enforcement agencies. In this system a piece of information is classified on three scales: the source is rated from A (always reliable) to E (untested); the particular information is evaluated from 1 (known to be true) to 5 (suspected to be false); and another scale from 1 to 5 indicates who can have access to the information.

In 127 cases, information is said to come from rated “sources”. But one fact leaps out: 98 of these are rated as E4: “untested source, information not known personally to source, and cannot be corroborated”; 19 were rated B2 “mostly reliable source, information known to source but not to officer”; one was rated B3 “Mostly reliable source, information not known personally to source, but corroborated”; eight were rated E3 “untested source, information not known personally to source, but corroborated.” In the other 57 cases the source evaluation was “not known, intelligence rating not shown or not clear in file”.

And there is further confirmation from the July 2016 ICIBI report on “Intelligence Functions” (para 6.11), which adds:

“In interviews and focus groups, staff commented that IE was overly reliant on allegations received from members of the public, and did not gather enough intelligence through enforcement teams and Field Intelligence Officers (FIOs). As a result, it was reactive rather than proactive. Their views echoed the 2014 Deloitte report, which found ‘some reliance on public allegations which are not the most efficient way for IE to direct its activity’.”

In conclusion, taken together, all the evidence suggests that Immigration Enforcement “intelligence” very largely consists of uncorroborated tip-offs from unknown “members of the public”.

However, we should add one last point. Immigration Enforcement has strong political, and indeed legal, reasons to represent itself as “intelligence led”, as not conducting “fishing expeditions”. For this reason, we might expect that available data under-represent operations carried out on the basis of no allegations at all. This would also hold for the Operation Centurion leaked documents. If ICE teams are regularly “cold calling” high street takeaways, this may not get written up as such even in internal case notes, and above all not for a showcase operation. However, it could be that many of the 57 cases in the ICIBI sample without any source ratings were just this kind of “speculative” operation.

So our general conclusion might be: most IE intelligence comes from uncorroborated public informing; whilst some operations may not be based on any intelligence at all.

3. Employer collaboration

In the Byron’s Hamburgers case, Immigration Enforcement arranged with the company to carry out a “sting operation” on its workers. Managers called in targeted staff for early morning meetings, described as about “Health & Safety”, or “a new kind of hamburger”. When they arrived they were met by ICE immigration officers, who made 35 arrests in different restaurants.[xxi]

A few weeks before, on 2 June, Immigration Enforcement raided the London training centre of Deliveroo, the food delivery courier company, whose workers have recently been protesting about a cut in wages.[xxii]i The raid was a joint operation with police (focusing on drugs) and the Department of Work and Pensions, and ended with three arrests for immigration offences. Workers present said that Deliveroo management actively assisted the raid and, according to one online report, Immigration Officers arrived with “a list of names with photos of Deliveroo drivers they were looking for”.[xxiii]i In a media statement the next day, a Deliveroo spokeswoman confirmed that: “we have worked with the Metropolitan Police to assist in a documentation check at our Angel office yesterday.”[xxiv]

Two earlier high-profile cases occurred in May 2007 and 2009, both involving contract cleaning companies – Amey and ISS. In December 2006, Amey took over the cleaning contract at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Middlessex, and with it a workforce of 36 cleaners. The new contractor moved to “rationalise” staff numbers. The cleaners, who were seeking trade union recognition rights, resisted. Amey’s next move, as told by union rep Julio Mayor, was as follows:

“they summoned all the workers to a closed area under the pretext of a training session. 15 minutes after we had assembled, about 60 police and immigration officials arrived and took away six people undocumented in the UK. Part of the policy of Amey was to get rid of the workers who were working there before they won the contract and they used every tool they had. All the workers were Latin American.”[xxv]

In June 2009, ISS, the cleaning contractor for the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, made a very similar move against its largely unionised staff. “Cleaning staff were told to attend an ‘emergency staff meeting’ at 6.30am […] Within minutes the meeting was raided by at least twenty immigration officers. The cleaners were locked in the room and escorted one-by-one into another classroom where they were interrogated.” Two members of university management were also reportedly present.[xxvi]

How common are these kinds of operations? Unsurprisingly, official data doesn’t reveal this. The Amey and ISS cases came to light because some of the workers targeted were active trade unionists and campaigners who raised a public outcry. The case of Byron, too, was initially reported in Spanish speaking media, then raised by black activist groups on social media, and only picked up by mainstream UK press weeks later after the “#boycottbyron” hashtag went viral on twitter. We can suppose that there are more cases of this kind, which do not receive media attention.

The Op Centurion documents contain some evidence of this. But more than that, they show how sting operations are just one form of a much wider issue: the whole Immigration Enforcement approach to “illegal working” in fact rests on employer collaboration, which may take various forms and degrees. The most basic is informing on workers. In fact, we read the following bare statement in the Home Office’s official staff guidance on “Illegal Working Operations”:

“The majority of reports about suspected illegal working come from employers.”[xxvii]

How does that square with the evidence discussed above that the bulk of information starts with “members of the public”. One possibility is that employers are also included as “members of the public” in the figures, and the bulk of the 50,000 tip-offs come straight from bosses. We cannot rule this out, as the available figures do not break down sources further into types of informants. But another possibility, which perhaps fits better with the overall picture, is this: public tip-offs, anonymous or otherwise, are often the first lead; next, Immigration Enforcement typically follows these up by approaching employers, threatening penalties if the tip-off turns out right, and demanding more specific details on “suspected illegals”. Very often, the employer agrees to turn informant. Sometimes, they also agree to more, such as helping to set up a sting. So, even if the initial informants are not employers, they then play a key role in developing these leads.

Going through the Op Centurion files, 18 entries explicitly mention discussions between Immigration Enforcement and employers. The IE staff involved in these discussions may be ICE immigration officers, or intelligence staff such as “Field Intelligence Officers” (FIOs). As many of the Op Centurion files concern cases in early development, some of the references are to initial plans to “contact” or “engage” employers. The fact that contact often seems to be initiated by Immigration Enforcement supports the pattern we just sketched. For example, Midlands ICE teams plan to visit “markets and engage with managers there and do some intelligence gathering there”. In London, “contact to be made with Berkeley Homes over a large construction site in Greenwich”. In another case, “contact made with Holiday Inn […], awaiting return contact from HR”.

In other cases, the entries report that relationships have been established and the company is co-operating. This co-operation may involve a number of features. The most immediate, and common, is handing over staff files and other information on workers. E.g.: “Contact made with Coral Bookmakers and William Hill bookmakers for sites across South London, 900+ staff files are being checked and it is conservatively anticipated there will be at least 5 offenders across the sites.” Or in a care home: “staff list of 95 obtained and 8 offenders traced.” One entry mentions the “British Horse Racing Association” “providing staff details (which we have not yet received)” on stable workers. (Another entry describes the “Horse Racing Association” as “keen to engage with HOIE [Home Office Immigration Enforcement] and we are taking this forward”.)

Three of the entries that mention employer contact concern recruitment agencies. One case note reads as if possibly the initial approach came from the company: intelligence officers are planning to visit the agency after “they noticed an increase in Africans submitting ITA[lian] ID cards and [passports].” Another interesting entry refers to a visit by FIOs to a recruitment agency where “12 offenders were identified”. It ends: “residential visits to be tasked”. That is, it seems, the agency is passing on home addresses of people on its books looking for work, so that ICE can then raid their houses.

As well as passing information on workers, employers may also point the finger at other employers. Two cases are mentioned in the files: in both, Immigration Enforcement is “contacting” or “in communication” with companies – a car auction site and a cinema chain – about their cleaning contractors.

Finally, we come to two entries that may indeed refer to Byron-style operations where arrests are set up “by appointment” with bosses. One from the South East team reads: “FIOs are liaising with cleaning companies with a view to arrests by appointment being made.” The other is from the South Central team: “FIO looking at a mid size warehouse […] which is owned by a Chinese national. FIO’s are still liaising with cleaning companies with a view to arrests by appointment being made.” Given the very similar wording, these two entries may indeed be talking about the same operation: apparently a large operation against a number of companies, and across at least two local ICE areas.

There is one entry in the documents about an employer, or in fact an employers’ association, not cooperating. Officers contacted the association “to establish information flows however this is looking unlikely due to a reluctance to work with Immigration Enforcement”. This is the only case of non-cooperation noted in the documents. Of course, other potential cases may not have made it into the files for precisely that reason.

The Op Centurion files suggest that it is very often Immigration Enforcement, acting on a prior tip-off, who initiate contact with employers. This seems to make sense: under most circumstances, why would it be in an employers’ interest to “bring down heat” on themselves? After all, one of the perks of “illegal” labour is that it’s not hard to fire workers.

Under most circumstances, that is. We can also think of exceptions. For example, an employer might be unwilling to do their own dirty work of firing workers, perhaps because of social or family connections to workers. Or some employers may be keen to have help in taking on a “difficult” workforce, perhaps where workers are organising. This, of course, is exactly the situation in which Amey and ISS set their stings –and more recently, in which Deliveroo worked with police and Immigration Enforcement. It would be worth investigating further the specific use of these tactics in relation to workplace disputes.

“Educating” employers

In the two years since Operation Centurion, there is strong reason to believe that employer collaboration has become still more central to Immigration Enforcement practice. In the second half of 2014, the Home Office ran a programme called “Operation Skybreaker” to pilot a new enforcement approach in the ten areas of highest “known” illegal immigration – all in London. The new model has since been rolled out nationally. The theory was about “moving from a model that seeks predominantly to arrest and remove individuals, to a model that seeks also to prevent illegal migration, drive compliance with the entirety of the immigration rules and tackle the underlying causes of illegal migration including criminal activity’.xxviii

In practice, the main change was the introduction of so-called “educational visits” in advance of raids. “Before making an enforcement visit to a business to follow up information received about individuals suspected of working there illegally, IE would first visit the business to encourage them to comply with employment requirements.”xxix

These visits serve a number of objectives. One is about public image: Immigration Enforcement is now a friendly resource informing employers of their rights and responsibilities, “encouraging” rather than punishing. Another is about scaring workers into voluntary return, much cheaper than forced deportation. But, as the Anti Raids Network has highlighted, there is also another very important, if less publicised, role of these visits: to approach employers about collaboration, whilst gathering more intelligence.xxx Indeed, the Home Office’s evaluation of Operation Skybreaker specifically states that “Intelligence generated” from educational visits in the pilot “led to 65 arrests”.xxxi

Whereas actual arrests have to be formally documented, there seems to be little recording of what happens in “educational visits” – the ICIBI report notes that “the recording of engagement with local businesses and stakeholders needed more effective management.” Nonetheless, the ICIBI reports give some ideas of standard forms of “engagement”. The most basic one is demanding to see records of employers’ “right to work” checks: the Op Skybreaker evaluation noted that half of businesses failed to show these.

It’s worth pointing out here that there is no legal requirement for businesses to show “right to work” check records on demand during an “educational visit”. (In fact, as the ICIBI report notes, some police forces advise employers not to keep them on the premises.) The legal purpose of “Right to work” check records is to serve as evidence, after a raid that discovers “illegal working”, that an employer did not employ these workers knowingly or negligently, and so avoid a penalty. Clearly, however, they serve another function for Immigration Enforcement: a way to get information on workers in advance of planning a raid.

Are firms forced to collaborate?

This last point brings up an important question. In the Byron Hamburgers case, many of the chain’s media defenders argued that it had no legal choice but to co-operate with Immigration Enforcement in setting a trap for its workers. As we will now see, this is not the case. The choice was not legal but financial. Also, it would only need to be faced at all if Byron’s had knowingly or negligently employed “illegal workers”.

The relevant basic points are these:xxxii

- It is a criminal offence to employ someone if the employer “knows or has reasonable cause to believe that the person has no right to do the work in question”.xxxiii For example, an employer could be convicted if the court finds that they “deliberately ignored information or circumstances” about the worker’s status.

- In addition, an employer is also liable to pay a civil penalty for employing someone who doesn’t have the legal right to do the work. This is separate from the criminal matter – Immigration Enforcement can impose a civil penalty simply by issuing a notice, without having to go before a court and prove that the employer “knew or had reasonable cause to believe”.xxxiv

- But the employer can get out of paying the penalty if they can show evidence that they have a statutory excuse. Namely: that they have “correctly carried out the prescribed right to work checks using acceptable documents”. Carrying out the checks correctly involves, amongst other things: checking the worker’s ID documents before employment starts, and again at intervals if the worker has time-limited work permission; and not accepting these documents if it is “reasonably apparent” that they are false or do not belong to the worker.xxxv There is a Home Office “statutory excuse checksheet” which states clearly what evidence Immigration Officers should look for when judging whether employers made the checks correctly. Basically this amounts to two things: a clear copy of the relevant pages of the worker’s passport or other acceptable ID document; and a record of the date when it was checked (for example, by dating the ID document copies).xxxvi

- If the employer fails to show it has done the checks correctly, and so does have to pay a penalty, this can be reduced on certain grounds, including reporting illegal workers and further co-operating with Immigration Enforcement. The maximum penalty is £20,000, or £15,000 if the company has not been found employing an illegal worker during the last three years. But the following reductions can be applied:xxxvii

- £5,000 for reporting the suspected illegal workers to Immigration Enforcement;

- £5,000 for “actively co-operating”, which means doing all of the following four things: “providing Home Office officials with access to your premises, recruitment and employment records and document checking systems when requested; responding promptly, honestly and accurately to our questions and information requests; making yourself available to our officials during the course of our investigations if required; and fully and promptly disclosing any evidence you have which may assist us in our investigations”;

- £5,000 for “evidence of effective document checking practices” (but only applicable if not found to have employed illegal workers in the last three years);

- 30% further reduction for paying within 20 days (again, only applicable if not caught in last three years).So if this is the first offence in three years, and if the company reports its workers, co-operates fully with all further demands, and shows effective document checking, it can have all penalties waived. If it can’t show effective document checking, it can get its penalties down to £3,500 by informing, co-operating fully, and then paying promptly.

If it has been caught in the last three years, it can get its penalties halved to a minimum of £10,000 by reporting illegal workers and then fully co-operating with further Immigration Enforcement demands. This may have been the situation faced by Byron, as the company had been caught employing at least one illegal worker in 2015.xxxviii

We can note a few points:

- An employer only faces a penalty for accepting false documents if they are obviously fake. For example, the Independent Chief Inspector specifically discusses a case where the CPCT penalty team: “considered that the identity documents provided by many of those arrested were fraudulent, but determined that this was not ‘readily apparent’ so canceled all but one civil penalty.”xxxix As the Inspector puts it,“employers are either negligent in respect of their obligations to check their employees’ ‘right to work’ or complicit in hiding such work from the authorities.”xl To pick up some of the discussion of the Byron Hamburgers’ case: the company should not have faced any penalties if it had just been “tricked” by cleverly forged documents.

- There is no general legal requirement for companies to hand over documents requested by Immigration Enforcement in advance of a raid. Companies may choose to do so in order to provide evidence that they have correctly applied right to work checks. This will only be relevant if Immigration Enforcement in fact finds illegal workers, and so the employer needs a statutory excuse. So, if a firm is confident that it has no illegal staff, it is within its rights to refuse to give information Immigration Enforcement. (In fact, it is within its rights to do this even if it does have illegal workers – although it won’t then be able to use a “statutory excuse” if Immigration Enforcement catches them. And probably this would not look good if a court case did result.) As we will see below, Immigration Enforcement acknowledge this fact by (at least sometimes) asking employers to sign “consent forms” authorising access to staff records.

- If a company does provide documents to show a statutory excuse, it only needs to provide those that are directly relevant: i.e., ID document copies, with records of the dates when these were checked. It does not have to hand over further personal information such as workers’ home addresses.

- But while there is no legal obligation to hand over these documents ahead of a raid, or otherwise co-operate, there are financial incentives – unless a firm is fully confident that no illegal staff will be found.

Multi agency ops

One way Immigration Enforcement might increase its ability to persuade employers to collaborate is by working together with other agencies who have greater powers or can add other forms of sanction. We looked above at some examples of intelligence sharing between agencies, and also saw statistics that suggest this is a major source of “leads” for IE operations. As well as sharing intel, agencies often work together on larger operations, and the Government is encouraging further development of such teamwork.xli

In the Operation Centurion documents, 25 cases mention Immigration Enforcement working with at least one other state agency in some capacity, from sharing intelligence to full on multi-agency “joint operations”. In ten cases this includes police, including one case with the British Transport Police (BTP) relating to railway workers. HMRC is involved in four cases, the Security Industry Authority (SIA) in three, and the Department for Work and Pensions in two.

Besides the police, the most common partners are various Local Authority departments. These include: environmental health and food hygiene (to coordinate joint operations against restaurant and food preparation businesses), market regulation, liquor licensing (targeting restaurants and shops), taxi licensing (intelligence gathering or joint operations against taxi firms), and planning (to gather information on large building sites).

The Op Centurion documents also show a number of extra-large collaborations, including one that musters a veritable army of multi-agency officials to target an unlucky group of restaurants in the West Country: “Approaches have/will be made with HMRC for a physical presence, Liquor licensing, Council food hygiene, Police and we are exploring any others we can bring in. Contact with the Police Area Deputy Commander and he has already tasked us some personnel and custody/support.”

Members of the Anti Raids Network have suggested that these multi-agency operations can also serve purposes that go beyond immediate “law enforcement” objectives. For example, a report on a series of raids of Deptford High Street in South East London links immigration raids co-ordinated with Lewisham council departments to the gentrification of the area and the “Deptford Project” development scheme.xlii

Conclusion: pressure to collaborate

We have seen from the Operation Centurion documents a few basic forms of employer collaboration. The most common appears to be handing over “staff records”, which may sometimes include detailed personal information such as home addresses.

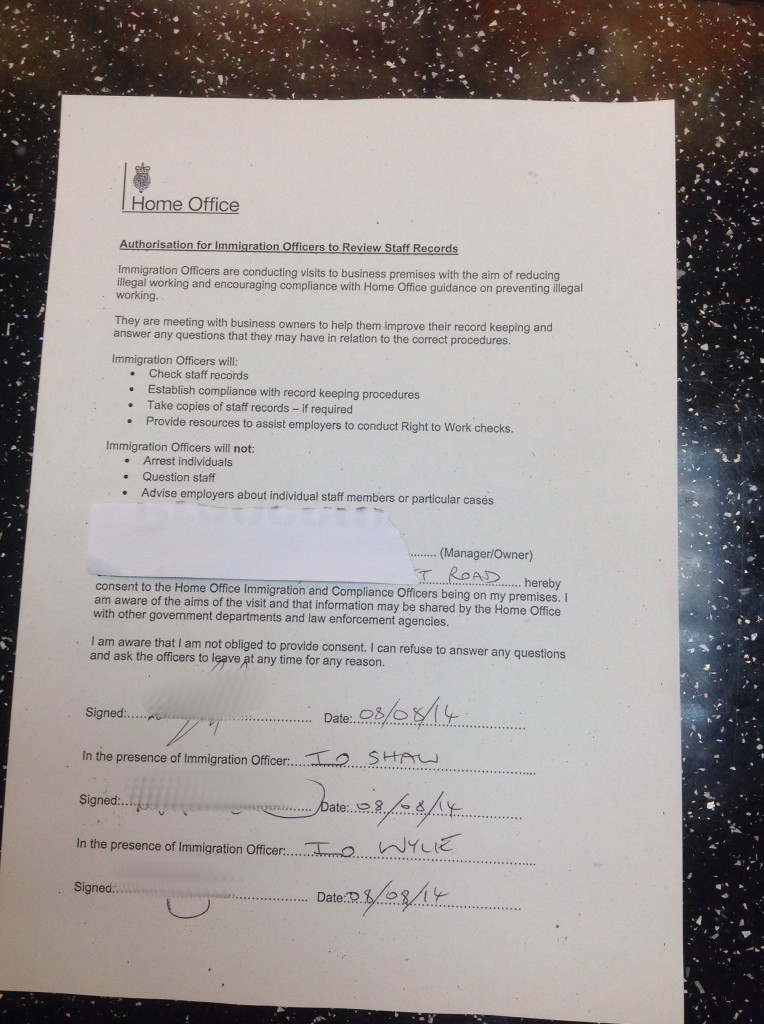

In September 2014, the Anti Raids Network published a copy of a “consent form” that Immigration Enforcement had presented to a business during Operation Skybreaker, demanding that they sign. This form was headed “Authorisation for Immigration Officers to review Staff Records”. It gives permission to Immigration Enforcement to enter the premises and to “check staff records; establish compliance with record-keeping procedure; take copies of staff records – if required; provide resources to assist employers to conduct Right to Work checks”. It states that the visit would not involve arresting or questioning staff. The gathered “information may be shared by the Home Office with other government departments and law enforcement agencies”.xliii

The form also states clearly, above where business owners are asked to sign:

“I am aware that I am not obliged to provide consent. I can refuse to answer any questions and ask the officers to leave at any time for any reason”.

As this makes clear, Immigration Enforcement is well aware that companies are not legally obliged to hand over personal information on workers in these visits. However, Immigration Enforcement officers have certain leverage that they may apply in order to persuade employers to co-operate – and indeed to “report” suspicions about any workers:

- the most direct threat is that if companies refuse to do so they will not be treated as “co-operating”, and so will face full penalties if a raid finds illegal workers;

- in addition, Immigration Enforcement could threaten to involve other agencies (licensing, food hygiene, etc.), whom employers may have cause to fear on other grounds;

- Immigration Enforcement may also threaten that non-cooperation will be viewed negatively in the case of an eventual criminal prosecution. This threat has become more serious with the 2016 Immigration Act, under which it is now a crime not just to employ workers you know to be illegal, but if you had “reasonable cause to believe” them to be; xliv

- finally, the threat of being raided, in itself, may have some effect: even if no “illegals” are discovered, a raid can involve inconvenience, humiliation, and lost business. Whereas “arrests by appointment” can be arranged to minimise problems for the business, e.g., before opening hours as in Byron’s case.

Anecdotally, members of the Anti Raids Network have confirmed that this is what often happens at an Immigration Enforcement “educational visit”. Intelligence officers or ICE teams call into a business, or sometimes telephone. They ask for full staff lists, and may demand further information on specific individuals. The threat, made implicitly or explicitly, is that if firms do not hand over all information requested they are likely to face a hostile raid. Non-cooperation will lead to higher penalties, and possibly criminal charges, if “illegals” are discovered. Penalties can be brought down potentially as low as zero if employers indeed “report” suspect workers. It may take a particularly confident employer to resist these pressures.

On the subject of consent forms, the Anti Raids Network has written:

“During our outreach, we have found that a lot of people have been signing consent forms. However, when we’ve told people that there is no obligation to sign, many said that they were unaware that it was voluntary, while others said ‘you can’t do anything to stop them – they do whatever they want’. In practice of course, it is very hard to refuse – regardless of whether this is your legal right.”xlv

We also saw in the Operation Centurion documents signs that officers may suggest more involved forms of collaboration such as helping to arrange “arrests by appointment”. There is no explicit mention of this as an officially recommended approach in any of the public documents we have seen. We may suppose that collaborating in this way helped Amey, Byron and others to be classed as “co-operating”, and so have several thousand pounds knocked off their fines. Perhaps the fines were waived altogether, even for firms recently caught employing illegal workers – but if so, this is going against the official published guidance, which clearly states a minimum of £10,000 for such firms.xlvi

Here we reach the limit of what we can learn from public or leaked Home Office documents. To research this question further, an obvious next step would be to interview employers and workers who have been subject to Home Office “educational visits”.

4. Fabricating consent

In many vampire stories, the undead can enter a building only when invited in by the occupiers. Immigration Enforcement often work on a similar principle.

In the ICIBI December 2015 report on Illegal Working operations, the Inspector looked at how raids were carried out for the sample of 184 cases. This included how ICE teams gained entry to targeted premises. In 79 cases, the teams had court warrants. In three cases, the power of entry was not clear in the records. In the large majority, 102 visits, the Immigration Officers entered without a warrant claiming that they had “informed consent” to do so.

Before we look at what “informed consent” amounts to, it is worth comparing these figures with others from a previous ICIBI report which attracted some attention. In 2014, the Independent Chief Inspector published, “An inspection of the use of the power to enter business premises without a search warrant”.xlvii More specifically, this report focused on the use of a particular power granted by Section 28CA of the Immigration Act 1971, called the “AD Letter”, in which under certain circumstances Immigration Officers can legally enter a business without a search warrant if authorised by a Home Office Assistant Director (usually, the head of a local ICE team).

This report noted that there were 3,568 illegal working visits nationwide between 1 April and 31 August 2013. In only 33% of these (1,178), ICE teams had search warrants. In 24% (860) they used AD letters instead.xlviii The report then looked at a sample of 59 cases and concluded that “only 17 of the cases we sampled (29%) justified using this power. In 35 cases (59%), we disagreed with the

AD decision and in a further seven cases (12%) there was insufficient information to enable us to form an opinion.”xlix In essence, an AD letter is supposed to be a last resort substitute for a court warrant in urgent cases – yet in 95% of the sampled cases, officers had just not considered getting a warrant. According to South London ICE staff, “the use of the power without a search warrant was routine because it was easier to get a signature from the AD than it was to attend a Magistrates’ Court.”l

In his forward to the report, the chief inspector summed up:

“In almost two-thirds of the cases I examined, I disagreed with the decision made by an Assistant Director to authorise the use of this power. This was because of weak justifications or because the need for swift action was not supported by the evidence. I was also very concerned to find six cases where the power appeared to have been used unlawfully, primarily because either the authorising officer was not at the appropriate grade or the power was not used within the time-frame set out in the legislation.”

Following the inspectorate’s strong condemnation, it is notable that the sample in the December 2015 report shows not a single use of an AD letter. It appears that, at least for now, ICE teams have back-pedalled away from this power. The “Illegal Working 2015” report observes: “Senior IE managers confirmed that the use of this power was now much more tightly controlled to ensure compliance with the legislation.”li

However, this doesn’t mean that ICE teams are now following the regular channel of applying to a magistrate’s court for a warrant in most cases. In the sample in the December 2015 report, teams only had valid warrants in 43% of raids (79 cases) – an improvement on the 33% counted in the 2013 figures, but still not the norm. Instead, it appears, where teams once wielded an AD letter they will often now rely on claiming “informed consent”.

Informed consent, according to Immigration Enforcement guidance, means “a person’s agreement to allow something to happen after the person has been informed of all the risks involved and the alternatives”. lii The Chief Inspector’s report further clarifies that “the guidance requires ‘fully informed’ consent in writing by a person ‘entitled to grant entry’”.

How often does this happen? We can’t know for sure – but we suspect not very often. As the inspection report notes, there is not much of a paper trail on how “informed consent” was established. The records seen by the Chief Inspector “did not note specific enquiries to comply with the requirement to establish that the person consenting to entry must be ‘entitled to grant entry’. In most premises visited, English was not always the first language of those encountered.” In general: “Files rarely documented how officers confirmed that consent was ‘fully informed’ as required.” liii There seems to be no requirement for teams to keep signed consent letters on file and available for inspection. There is then no way for the genuineness of “consent” to be proved or disproved, or for the officers involved in gaining “consent” to be held to account. Moving away from AD letters to reliance on “informed consent” has in fact made ICE operations even less accountable and open to scrutiny than before.

The report features a particular case study in which the team “decided to gain entry by informed consent” and subsequently “noted in the case file that ‘verbal authority’ to enter was given and then withdrawn as soon as the name of the person they were seeking was disclosed”. After the Chief Inspector raised concerns about this case, commenting that “ ‘verbal authority’ is not a recognised term”, the Home Office responded that:

“The ICE team has recognised this is a case where an application for a search warrant would have been appropriate, but there is no record of why an application wasn’t made;

• where practicable, consent must be given in writing before a search begins. We would not have expected the search to begin before the written consent was obtained;

• we have recognised that clarification of the procedure to be followed to obtain informed consent was required and this was published to staff in December 2014.”liv

Anecdotally, we are told by the Anti Raids Network that it is very common for raids to take place in the following way: ICE officers turn up at the door and ask to speak to the manager, while other officers may already have sealed off other exits to prevent people from leaving the building; the officers then ask the manager (or an available worker) for verbal consent to enter the premises, or at best to sign a paper granting written consent on the spot.

This is clearly not sufficient for “informed consent” in any meaningful sense, or as recommended by the Home Offfice’s own guidance. To highlight a few obvious issues:

- permission to enter is not sought in advance of the raid;

- instead, it is granted in the heat of the moment, during a fraught situation in which a team arrives with intimidating force;

- it is unlikely in this situation that the person approached is “informed of all the risks involved and the alternatives”;

- particularly as, often, ICE officers do not communicate in a language the person clearly understands;

- in addition, the ICE team may not properly establish that the person they are talking to is actually entitled to grant informed consent;

- and permission may often not be sought or given in writing.

Finally, we can note that this situation with respect to consent to enter is mirrors the common failure of Immigration Enforcement to gain consent for questioning. The law and Home Office guidance allows Immigration Enforcement to enter premises in pursuit of specific named individuals suspected of immigration offences – again, this is key to the claim of “intelligence led” operations. Officers do not have a general power to question anyone who is not the named offender. They may, however, “invite” other people to answer “consensual questions” if “they had brought themselves to attention, such as by ‘behaviour (for example an attempt to conceal himself or leave hurriedly)’.”lv

Once again, the ICIBI report on “Illegal Working Operations” shows that Immigration Officers routinely break the rules. The report states succinctly:

“In the 184 files we sampled there was no record of anyone being ‘invited’ to answer ‘consensual questions’. The files showed that officers typically gathered everyone on the premises together, regardless of the information known or people’s actions.”lvi

I.e., although most raids do appear to be initially targeted based on some form of (low grade) “intelligence”, once inside the building they typically become a general round-up.

However, we can suppose there are also some occasions where Immigration Enforcement do genuinely have employers’ “informed consent” to enter premises. This was clearly the case in the sting operations set up with Amey, ISS and Byron. More generally, establishing “informed consent” may be one possible objective of pre-raid “educational visits” – although, it seems clear, ICE teams are not too bothered if in the end it is lacking.

Again, the obvious way to investigate further the actual circumstances under which “consent” is claimed would be to survey employers and workers about their experiences both in raids and in pre-raid visits.

Immigration van blocked during resistance to raid on East Street Market, 21 June 2015

Conclusion: what are raids for?

“A senior Home Office manager told us that there was a general awareness within IE that enforcement visits encountered and removed only a small proportion of offenders and that IE would never have the resources to resolve the overall problem. They described it as ‘not a realistic working model’. Another senior manager commented: ‘It’s a business model that hasn’t moved on’.”lvii

It most often starts with a tip-off, an “allegation”. Or, sometimes, with a referral from police or other agencies, or maybea speculative “cold call”. Astandard next step is then to approach employers and seek their collaboration. Typically, employers are asked to hand over lists and details of workers, in order to identify “illegals” who can then be targeted at work or at their home addresses. Sometimes, this collaboration may lead to “arrests by appointment”, as in the sting operations infamously launched with cleaning contractors Amey and ISS or recently with Byron’s Hamburgers.

Employers are not legally obliged to collaborate in any of these ways – though if they don’t, they may face higher financial penalties if illegal workers are found on their premises. ICE teams don’t need employers’ collaboration, and are seemingly happy to claim “informed consent” to enter, or consent to question unnamed individuals, with no justification whatsoever. But employer collaboration certainly makes their work much easier: it provides the “majority of reports about suspected illegal working”, and will increase arrest numbers both at workplaces and at workers’ homes.

And yet, even with maximum co-operation, Immigration Enforcement catches only a tiny proportion of people working illegally. As we saw, each year the Home Office carries out around 6,000 workplace raids, and makes around 5,000 arrests, half of which lead to deportations.

For obvious reasons, there are no reliable figures on numbers of illegal workers. The most widely quoted research on “irregular migrant” numbers in the UK remain those from a study carried out by the London School of Economics (LSE) in 2009, which gives an estimate of 618,000, in a range of 417,000 to 863,000.lviii Not all of this number are working: the estimated figure includes underage children, the elderly, and other dependents, as well as a supposed higher proportion of unemployed adults than the norm. However, there are also other “illegal workers” who would not be counted in the LSE estimates: e.g., asylum seekers or people on student visas who are not “irregular” as residents but do not have the right to work.

Any number we use would be a simple guess. But even supposing “illegal workers” to be as few as 250,000, this would mean that only around 2% are arrested in a year, and only 1% deported.

Immigration Enforcement does not stop or deter those must work as a necessity, work to survive. Or work to save or send money to family and loved ones, in a world where even the sub-minimum wages paid to many “illegals” in the UK (the illegal “discount” referred to by Shahram Khosravilix) are generally far above wages in its former colonies or its warzones. But it does mean that anyone living in the world of migrants will know people who have been raided, who have been arrested, who have been detained and deported. So the reality and the fear of Immigration Enforcement seeps into life every day, to be always a shadow cast around the corner.

Immigration Enforcement does not stop people working illegally – but it makes them work fearfully. Immigration Enforcement helps maintain a segregated “two tier workforce” in which hundreds of thousands of workers have no access to the rights or safeguards available to other workers. The fear of Immigration Enforcement keeps workers in the lower tier scattered, unseen and unheard. The threat of Immigration Enforcement provides the ultimate human resources tool to stop workers becoming “difficult” and organising to demand improved rights or conditions – as seen in the cases of Amey or ISS.

This is not an issue just of a peripheral minority. Illegal working is at the heart of the economy. Illegal workers are not just in the restaurants or street markets that make easy and symbolic targets for ICE raids. They are the base level of the driving sectors of the UK economy: building workers, office cleaners, food pickers and packers, warehouse lifters, drivers and couriers, the menials in every service industry. The “discount” on illegal workers makes a fundamental contribution to every business model. Every blue chip company relies on illegal labour. Which is not, for them, illegal – so long as these workers are not directly employed. Only the base level contractors or sub-contractors who immediately hire cleaners or labourers are liable for “right to work checks” and penalties.lx As we saw, one Immigration Enforcement tactic is to approach higher tier companies for information on contractors. Raids are, usually, kept at base level leaving the “respectable” companies unscathed.

To summarise, we can say that Immigration Enforcement does not work to end illegality, but it does work to maintain it in a segregated “lower tier”. The main way it does this is by spreading fear and division. Raids are exemplary punishments – propaganda tools.

Furthermore, the propaganda of Immigration Enforcement has a double focus. On the one hand, it targets illegals. On the other, it targets the legal population. Hence the press releases, high-profile operations, tabloid exclusives, camera crews invited on raids, and former initiatives such as the “racist van” billboardslxi and “UK Border Force” TV showlxii, etc. – the spectacle of enforcement. The illegals should fear Immigration Enforcement; the legals should fear the illegals, as they fear for their jobs, their homes, their “way of life”.

Home Office managers know that they will “never have the resources to resolve the overall problem”.Conscientious officials may well yearn to resolve the problem, whilst privately admitting that they best they can hope for is to achieve a few minor efficiency gains. But while the “problem” continues, business profitsfrom scared and discounted labour, and politicians and journalists make careers being tough on immigration.

i https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jul/31/bugging-byron-activists-release-cockroaches-and-locusts-at-burger-chain

iii The Operation Centurion files have not been published themselves because they contain personal information naming businesses and sometimes individuals. In this report we quote from the files and anonymise where necessary.

iv In writing this report we have benefited greatly from the advice and assistance of members of the Anti Raids Network. This network has been actively campaigning against immigration raids in London since 2012, in which time people involved have not only helped resist many raids but have amassed a wealth of information. See the network’s website https://network23.org/antiraids We also thank Anti Raids Network for the use of images from their website.

v Some detail on the grades of Immigration Officers and their training can be found in the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) report on “An Inspection of How the Home Office Tackles Illegal Working”, para 6.8. http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ICIBI-Report-on-illegal-working-17.12.2015.pdf Hereafter, we will refer to this report as “ICIBI Illegal Working 2015”.

“New enforcement officers had 25 days of initial training covering 66 modules. Other training included a three-day ‘refresher package’, which had been expanded from two days, and a three-week ‘Arrest Training’ course, which covered ‘ACPO approved arrest techniques’ and was provided by the College of Policing. 6.9 Experienced officers in ICE teams mentored new Assistant Immigration Officers (AIOs) from their arrival after initial training until they were assessed to have met the requirements to become Immigration Officers (IOs). This development ‘pathway’ was tailored to each individual, but was expected typically to take around 18 months. We found that IE had no formal training for mentors to support consistency of practice across the 19 ICE teams.”

vi There are four regional intelligence teams, their official title is “Receipt, Evaluation and Development” (RED) teams.

vii A basic point to note is that the majority of “immigration offences” are not in fact “criminal offences” – although this may be changing, as Government moves to criminalise “illegal immigration” with legislation including the Immigration Act 2016 that now makes “illegal working” a criminal offence.

viii IE’s claims to be “intelligence led”, and the recent measures it has taken on this score, are discussed in detail in the recent ICIBI report “An Inspection of the Intelligence Functions of Border Force and Immigration Enforcement November 2015-May 2016” published July 2016 (hereafter ICIBI Intelligence 2016). http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/An-Inspection-of-the-Intelligence-Functions-of-Border-Force-and-Immigration-Enforcement.pdf

ix We don’t currently have data on the proportion of raids that target illegal working. But, also, bare numbers of raids wouldn’t really give a full picture, as workplace raids may vary from small corner shops to major ops on big factories, or big employers working across a number of ICE team areas.

x Home Office: Immigration Removals, Enforcement and Detention – General Instructions: Illegal Working Operations v1.0 July 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/537725/Illegal_working_operations_v1.pdf

xiI CIBI Illegal Working 2015

xii The Home Office does not standardly release “visit” figures, but only numbers of arrests. Hence we cannot say what proportion of all immigration “visits” are to workplaces. We do have some total figures just for London, thanks to Freedom of Information requests (FOIs). According to FOI data released by the Anti Raids Network in 21 May 2015: “Enforcement Teams in London conducted 12,026 ‘visits’ to homes, businesses and other sites in 2014.”https://network23.org/antiraids/2015/05/21/countering-camerons-call-on-immigration/ According to FOI results published by Philip Kleinfeld in July 2016: “The comprehensive data set, which breaks down raids in the capital by individual postcodes, shows a total of 19,853 raids — almost 11 a day — from 2010 to 2015. Immigration raids in London peaked in 2014 with 4,703 raids, up from 2,531 in 2010. In 2015 the number dropped by around 3% to 4,573. The areas of London targeted the most are E15 (1,396), E6 (776), E7 (637), SE1 (554) and SE18 (540). Arrests following raids or visits by immigration enforcement teams peaked in 2013 with 3,393 arrests. This fell to 2,616 in 2015.” https://medium.com/@PKleinfeld/immigration-raids-in-london-soar-by-80-edf00d1e2a5d#.73m1hbkqm

NB:These two sets of figures appear to contradict each other: the number released to Kleinfeld for 2014 visits is less than half that given in response to the earlier request. This does not seem to be because of the “raids”/”visits” terminology: in fact the official term used in the responses to Kleinfeld is “raids/visits”. One factor may be that Kleinfeld’s figures only cover the main London postcodes (N, NW, E, SE, SW, W), and not outer London areas with other postcodes – but this seems unlikely to explain all of the discrepancy.

xiii Home Office reply to FOI request submitted by Nadeem Badsha, January 2013. https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/immigration_raids#incoming-351316

xiv ICIBI Illegal Working 2015 para 5.3

xv “The Home Office response to the Independent Chief Inspector’s report: ‘An Inspection of How the Home Office Tackles Illegal Working’” https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/486703/Home_Office_Formal_Response_to_ICI_Illegal_Working_report.pdf

xvi On ICE recces see ICIBI Illegal Working 2015 para 5.11: “Twenty of the 40 files we examined in depth contained detailed recces. The other 20 either lacked basic information or contained confusing or contradictory details. A senior manager told us that poor recces had been identified as a problem, and another said that consideration was being given to not requiring a recce for every visit.”

xvii ICIBI Illegal Working 2015 para 7.13

xix The Intelligence Management System (IMS) is the main information recording system for Immigration Enforcement, also used by Border Force. See the 2014 ICIBI inspection report on the system for details: http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/An-inspection-of-the-Intelligence-Management-System-FINAL-WEB.pdf

The Home Office also has been using a system called ATHENA , provided by Serco, to record staff intel. This was due to be switched off and replaced in May 2016. IE intelligence officers also have access to various other internal or cross-agency computer systems and are supposed to use these to cross-check intelligence on targets. These include the following: CID; CRS (Case Reference System – a HO database containing details of all visa applications); Experian – commercial database holding credit reference information and personal information held by financial institutions; Warnings Index – a HO System used to ascertain whether individuals are of interest to the Home Office; Home Office National Operations Database; Police National Computer – https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/488515/PNC_v5.0_EXT_clean.pdf.. Source: ICIBI Intelligence 2016.

xx ICIBI Intelligence 2016. The IMS system was initially introduced in September 2012. This breakdown of sources was recorded in monthly IE performance data until July 2015, after which time “this data was no longer collected in this format.”

The figures here are similar to those for the year 2013, reported in the earlier ICIBI report “An Inspection of the Intelligence Management System” published in October 2014. This gives the following table of sources: Member of the public 54,894 73% ; Other (e.g. internal staff, police , etc) 12,070 16% ; Crimestoppers 8,315 11% ; MP’s 115 0.2% . Total 75,394. http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/An-inspection-of-the-Intelligence-Management-System-FINAL-WEB.pdf

xxi http://www.righttoremain.org.uk/blog/byron-burgers-legality-morality-humanity/ Also see Corporate Watch’s research on Byron Hamburgers’ offshore accounting: https://corporatewatch.org/news/2016/aug/01/byron-burgers-sending-millions-owners-offshore-while-workers-are-deported

xxviii ICIBI Illegal Working2015 para 4.13

xxix ICIBI Illegal Working2015 para 4.13

xxx Anti Raids Network analysis of Operation Skybreaker: https://network23.org/antiraids/2014/09/25/operation-skybreaker/

xxxi ICIBI Illegal Working2015 para 4.16

xxxii We note here that there is a good deal of ambiguity surrounding the law around raids, which makes it hard to state definitively what is or is not legally required. In particular, much of the relevant immigration law has never been tested in court – in part because those targeted in raids often disappear into detention or may indeed be deported. Also, some of the relevant legislation is very new, including the 2016 Immigration Act. Much of our account here sticks conservatively to Home Office internal guidance. But this is itself just an interpretation of the law and open to challenge in the courts.

xxxiii The 2016 Immigration Act added “has reasonable cause to believe”, which came into force on 12 July 2016. Prior to that, under the 2006 Act, the prosecution had to prove that the employer knew that the employee was working illegally. See the new issue of the government “Employer’s Guide to Right to Work Checks”: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/536953/An_Employer_s_guide_to_right_to_work_checks_-_July_16.pdf

xxxiv More precisely, the procedure is this: Immigration Enforcement (e.g., an ICE team) issues a “referral notice” to the employer stating that they have found illegal workers and that the case will now be handed to the “Civil Penalty Compliance Team” (CPCT); the employer has a chance to object; if the employer does not object or the objection is unsuccessful, they are issued with a second “Notice of Liability” that demands a payment; the employer can also appeal to a civil court to dispute the penalty. See “Code of Practice on Preventing Illegal Working”. See page 10 of that document for details of what it means to correctly carry out right to work checks. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/311668/Code_of_practice_on_preventing_illegal_working.pdf

xxxv More technically: having a statutary excuse is one of three grounds of objection or appeal to the civil penalty. The others are that the employer is not in fact liable (e.g., they weren’t really the illegal worker’s employer), or that the penalty is too high. See “Code of Practice on Preventing Illegal Working” https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/311668/Code_of_practice_on_preventing_illegal_working.pdf

xxxvii Full details are contained in the Home Office “Code of practice on preventing illegal working: code of practice for employers” May 2014 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/311668/Code_of_practice_on_preventing_illegal_working.pdf

xxxix ICIBI Illegal Working 2015 Figure 18

xl ICIBI llegal Working2015 Forward