Cost of charter flight deportations increased eight-fold over last decade

Cost-effective?

Since the UK government started using specially chartered flights for deportation purposes in 2001, the Home Office has always argued that, whenever there is a “sizeable pool of individuals to be removed to the same country, in these circumstances, removal by charter flight is more cost effective, reduces pressure on the detention estate and makes more cost- and time-effective use of escorts.”

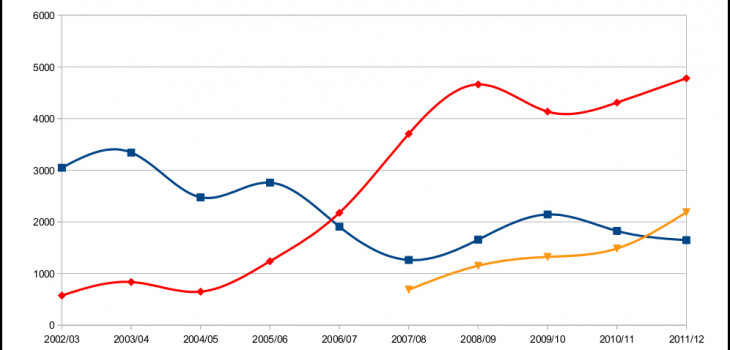

However, new figures obtained by Corporate Watch and Stop Deportation under Freedom of Information legislation show that the UK Border Agency’s annual expenditure on deportation charter flights increased from £1,752,991 in the financial year 2002/03 to £7,870,209 in 2011/12. At the same time, the number of people deported on these flights decreased from 3,048 to 1,647 over the same period.

This means the average cost of deporting one person by charter flight – as opposed to scheduled commercial flights – has steadily increased from £575 in 2002/03 to £4,779 in 2011/12 – that is more than an eight-fold increase. The average cost of a deportation charter flight rose from £68,796 to £218,617 over the same period. The graph below illustrates these trends.

The total cost of the programme has exceeded £50 million since 2002 (no data are available for the first year of the programme). Asked how they can explain or justify this increase in the costs of charter flight deportations, a UK Border Agency spokesperson insisted that charter flights “still represent the most cost-effective way of removing large numbers of people.”

Long haul

The UKBA had previously claimed the increased expenditure on charter flights is due to the agency’s returning more people to more long-haul destinations. However, a comparison of the newly released figures with other available data (the number of flights and the number of people deported to each country) reveals that this is simply not true.

In the financial year 2003/04, when the UK started forcible deportations to Afghanistan, 343 people were deported to the war-torn country, at a total cost of £1,239,661. In 2007/08, the figures had risen to 522 and £1,979,740 respectively. In 2011/12, they stood at 829 and £3,874,894. This means the average cost of deporting one person to Afghanistan by charter flight has jumped from £3,614 in 2003 to £4,674 in 2012 – a 29 per cent increase.

Similarly, the cost of deporting one person to Kosovo and Albania by charter flight rose from an average of £544 in 2002/03 (2,404 people deported at a total annual cost of £1,307,111) to £1,927 (221 people at a cost of £425,975) – a staggering 254 per cent increase.

Similar trends can be observed with other destination countries, such as Nigeria (a 121 per cent increase between 2008/9 and 2011/12) and Iraq (a 47 per cent increase between 2008/9 and 2010/11). The attached table shows detailed figures for each destination country since 2002 (no figures are available for the first year of the programme, 2001/02).

The other reason that the UKBA has cited to justify the increased expenditure on its charter flight programme is “the general increase in aviation costs over recent years.” However, aviation statistics, such as those provided by the UK Civil Aviation Authority (see here), do not seem to support this claim: The average increase in the cost of both scheduled and charter flights over the last decade is significantly less than that of deportation charter flights.

So how can one explain this then?

‘Excessive contractor staff’

The UKBA claims that, since charter flights “provide a controlled environment, the ratio of escorts needed per removal on a charter flight is lower than the ratio needed for escorted removal on scheduled flights. Escort costs overall are therefore lower for charter removals.”

However, the agency has admitted in a recent parliamentary debate that deportation charter flights often carry twice or three times more immigration officers and private security guards than deportees. In 2012, four flights had three times more staff than deportees and 15 flights had twice as many. In 2011, the figures were 2 and 22 flights respectively.

Last year, a parliamentary inquiry into the death of Jimmy Mubenga – who died in October 2010 after being ‘restrained’ by three G4S ‘escorts’ during his forcible deportation to Angola – found evidence of “excessive numbers of contractor staff” being used by the agency, “to the extent that HM Chief Inspector of Prisons believes that escort numbers are in some cases detrimental to the removal process.” This “excessive numbers of escorts,” the final report remarked, “is hard to justify against a background of reduced staffing levels across the public sector.”

In 2010, following the death of Jimmy Mubenga, Reliance Secure Task Management was awarded a four-year, multi-million contract with the UKBA to provide ‘detainee escort services’, replacing G4S. The company was bought up by Capita in August 2012 and renamed Tascor.

‘No review documents’

The UKBA claims that its deportation charter flight programme is “subject to ongoing review, and flight frequency and capacity [are] altered in response to changing demands of UKBA.” However, when asked for a copy of these reviews under Freedom of Information legislation, the UKBA’s Country Returns Operations and Strategy team (CROS) said: “There are no review documents.”

The emphasis appears to be on enforcing removals at any cost, so as to appear ‘tough on immigration.’ A UKBA spokesperson told Corporate Watch: “Charter flights are vital to ensuring we remove foreign criminals and individuals who refuse to leave the UK voluntarily.”

However, when asked in another Freedom of Information request whether the Home Office has carried out any evaluation of whether deportations by chartered flight have had an impact on the number and nationality of foreign nationals held in UK prisons, the department admitted that “no such evaluation has been conducted.”

Another motive appears to be the immigration authorities’ determination to suppress any possible ‘disturbance’ caused by people resisting or protesting against their forcible deportation. In 2009, the then head of Criminality and Detention at the UKBA, David Wood, admitted that the charter flight programme was “a response to the fact that some of those being deported realised that if they made a big enough fuss at the airport – if they took off their clothes, for instance, or started biting and spitting – they could delay the process. We found that pilots would then refuse to take the person on the grounds that other passengers would object. So although we still use scheduled ?ights, we use special ?ights for individuals who are difficult to remove and might cause trouble.”

In other words, and contrary to right-wing media claims about the ‘inefficiency’ of the programme and ‘wasting taxpayers’ money’ (see this classic example from The Sun, for instance), the UKBA appears to be well aware that charter flights are costing more but is happy to carry on with the programme exactly because it is effective as far as its political motivations are concerned: it serves the government to appear ‘tough on immigration’, while at the same time limiting migrants’ legal rights and ability to resist forcible deportations.

Corporate Watch and Stop Deportation, a UK-based campaign group focusing on charter flight deportations, are currently working on a joint report examining the various legal aspects of charter flight deportations.