Carceral Colonialism: Britain’s plan to build a prison wing in Nigeria

The British Government recently announced its intention to build a new prison wing in Nigeria. The 112-bed wing would be built at Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison in Apapa, Lagos State, Nigeria, and would enable the deportation of prisoners from the UK to Nigeria. The British state signed a Prisoner Transfer Agreement in 2014 with Nigeria but have been unable to deport people because of the poor conditions of Nigeria’s prisons.

This article presents Corporate Watch’s research on this alarming project; investigating the funding stream and bigger picture of carceral colonialism, as well as the racist criminalisation of foreign nationals and the trajectory that people face from prison to detention to deportation.

What we know so far

Foreign Secretary, Boris Johnson, announced the UK Government’s intention to build a prison wing in Nigeria via a written statement on the 7th March 2018.

The statement reads:

“On 9 January 2014, the United Kingdom signed a Compulsory Prisoner Transfer Agreement with Nigeria. As part of this agreement, eligible prisoners serving criminal sentences in Nigeria and the UK can be returned to complete their sentences in their respective countries. In support of this, and to help improve the capacity of the Nigerian Prison Service, the Government has agreed to build a UN compliant 112-bed wing in Kiri Kiri Prison, Lagos. Tenders have been placed and a supplier identified to conduct the building work, alongside project support and monitoring and evaluation, bringing the total cost to £695,525. This project is funded from the CSSF (Conflict, Stability and Security Fund) Migration Returns Fund.

The provision of this assistance is in line with the Government’s security and stability objectives in West Africa. FCO officials carry out regular reviews of our programmes in Nigeria to ensure funding is directed only to approved recipients.”

Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison was built in 1955, five years before Nigeria became officially independent from British colonial rule. The official capacity of the prison is 1,056 people. As of March 2018, the prison held approximately 5000 prisoners making it phenomenally overcrowded. According to research by the UN, 3700 of the prisoners had been awaiting trial for five years or more. It is one of 144 prisons and 83 satellite prisons across the country.

Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison was built in 1955, five years before Nigeria became officially independent from British colonial rule. The official capacity of the prison is 1,056 people. As of March 2018, the prison held approximately 5000 prisoners making it phenomenally overcrowded. According to research by the UN, 3700 of the prisoners had been awaiting trial for five years or more. It is one of 144 prisons and 83 satellite prisons across the country.

Following the announcement, the spokesman for the Nigerian Prison Service, Francis Enobore, said that the UK government had yet to formally notify it and the Federal Government of its plan. He said that,

“No such building can be built without a synergy between the UK and the Nigerian government; the UK cannot do that. There is no way the UK can just jump into Kirikiri and start to build anything. Officially, we are not aware of such move. No formal document has reached the service. As far as I know, I have not seen any document showing a formal move by the United Kingdom to build a prison wing in Kirikiri…I read about the plan. It is a proposal still being considered in the UK. There is no place where it is mentioned that any formal invitation was given to the Nigerian government. The Controller-General will be notified and there will be further plans. It is too early for me to start talking about a project that I have not seen or heard about.”

Prisoners are currently unable to be transferred to Nigeria due to the conditions of the prisons, which breach United Nation standards. In 2017, human rights investigators found that prisoners in the country were subject to ‘extrajudicial executions, torture, gross overcrowding and poor basic facilities.’ The country also still has the death penalty for crimes such as treason, homicide, murder and armed robbery. Rape, sodomy and adultery are also punishable by death under the Shari’a penal codes in some states. More than 527 people were sentenced to death in 2016, with more than 1979 on death row. Corruption is also a serious issue in the prison service, as is the fact that children and adults are being imprisoned together.

About the UK’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF)

According to the Government, Britain’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund has an annual budget of more than a billion pounds and aims to commission projects that can help prevent conflicts and stabilise countries or regions. It was established in 2015 and is guided by the National Security Council. Its budget was £1.16 billion in 2018.

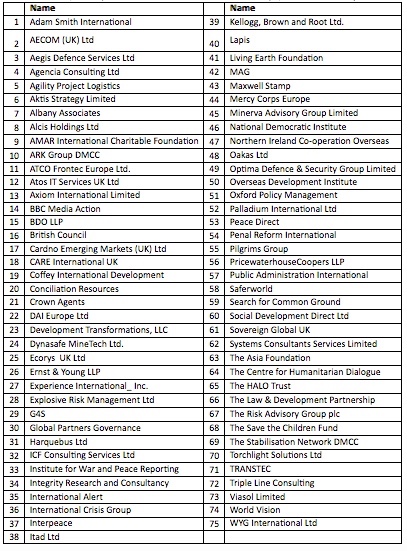

The fund is incredibly secretive. An annual report was produced due to transparency pressures yet it does not give a full list of funded projects nor the countries where the fund works. A new contracting framework is currently in development, however, below is the list of contractors known to date:

A report produced by Mark Curtis from Global Justice Now (GJN) in December 2017, brings the reality of CSSF to light. The Report titled ‘The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund: Diverting aid and undermining human rights’ describes how the CSSF is increasingly using aid money to fund military and counter-terrorism projects, including security forces in several states involved in appalling human rights abuses. Global Justice Now believe from their research that the CSSF is becoming a ‘slush fund’, effectively transferring money from the Department of International Development to other government agencies.

A report produced by Mark Curtis from Global Justice Now (GJN) in December 2017, brings the reality of CSSF to light. The Report titled ‘The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund: Diverting aid and undermining human rights’ describes how the CSSF is increasingly using aid money to fund military and counter-terrorism projects, including security forces in several states involved in appalling human rights abuses. Global Justice Now believe from their research that the CSSF is becoming a ‘slush fund’, effectively transferring money from the Department of International Development to other government agencies.

The fund is increasingly financing projects and programs relating to social control, policing, militarisation, and prisons. For example, £2.5 million was given to the Nigerian Police Force as ‘strategic assistance’. Police training was also funded in Sierra Leone to the sum of £2.31 million to provide training at senior levels in “public order management”.

The CSSF is undoubtedly used to strengthen states and their repressive apparatus. £3.25 million has been given to 11 projects in Bahrain. A Freedom of Information Request by GJN showed that these projects included a contract with Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons to build capacity in Bahrain’s prisons, and teaching Bahraini police how to ‘command and control’ demonstrators including sessions on ‘using less than lethal options’ such as water cannons and dogs, as well as evidence gathering and tactical advice.

Policing protestors in Bahrain. Source: https://d.ibtimes.co.uk/en/full/344734/bahrain.jpg?w=599&e=3bbbfebea0e18f28eaeb51b7f6bc55a4

Sayed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy said, “UK involvement goes beyond technical assistance, forming a spider’s web across Bahrain’s prisons, police, judiciary and now parliament, despite the majority of opposition leaders languishing behind bars, an unprecedented crackdown on civil society and a sharp deterioration in human rights. The UK is managing repression in an authoritarian regime, paid by the taxpayer.”

Example after example show the funding of repressive regimes, from courses for the Burmese and Sudanese military to police training in Sri Lanka (where torture by the police is widespread). Military vehicles were also donated to the Bulgarian government to help police its borders and capture and return refugees.

Carceral Colonialism

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/number10gov/21210642953

The prison wing in Nigeria is not the first prison-building project the British State has tried to initiate. In 2015, then Prime Minister, David Cameron announced plans to build a new prison in Jamaica for the same purposes – to allow the transfer of prisoners between the two countries. £25 million was offered to build a new prison for 1500 people as part of a £300 million aid package setting Jamaica up for increased trade and global exploitation. The package, that only covered 40% of the cost was eventually rejected by the Jamaican State.

Foreign Affairs Minister, Kamina Johnson told legislators that “the terms they (UK) have provided are not beneficial to Jamaica as a whole and so we (Government) rejected it.”

The offer by the British State to build a new prison wing in Nigeria is the continuation of a legacy of violence dating back to the slave trade in the 18th century, where Britain replaced the Portuguese as leaders of the trade in the region.

An organiser from the End Deportations Campaign said, “It was Britain that created the state which is now known as Nigeria – combining two very different regions – the North (then, primarily Muslim) and South (then, primarily Christian). The name “Nigeria” was chosen by the wife of a British colonial administrator. Nigeria was often used by the British as a base for attacks against other colonised countries in Africa – destroying self-sufficient ways of living, agricultural production – leading to famine and poverty.”

The first prison the British tried to build back in 1882 was relentlessly targeted by anti-colonialists, who were able to set it ablaze easily due to its construction with mud walls and grass thatch. In 1885, the colonial government imported bricks from England to the cost of £16,000 and rebuilt the prison.

Neocolonial power in the country continues with coercive bodies such as the International Monetary Fund steering production away from domestic agriculture to the resource extraction and fossil fuel industries. In December 2017, Amnesty International called for Governments in Nigeria, the UK and the Netherlands to investigate the Nigerian military’s campaign to silence the Ogoni people’s protests against Shell’s pollution in the country.

Aside from training Nigerian police in repressive tactics, the British state has also paid for the construction of a new Reception Centre for people being deported to Nigeria.

Foreign National Prisoners: Demonisation, Racism and the Prison industrial complex

Before 2006, most foreign national prisoners were simply let out of prison at the end of their sentences. This was before the recent national anti-immigration hysteria in racist tabloid newspapers (learn more in our upcoming report on migration and the media). Soon it became the Government’s imperative to deport as many ‘foreign criminals’ as possible. The 2007 UK Borders Act brought in by the Labour Government was a game changer. It stipulated that ‘foreign criminals’ serving sentences of 12 months or more are to be automatically deported and that all non-citizens sentenced to prison would be considered for deportation, whatever their circumstances.

The prison system itself was re-designed to enable greater numbers of deportations. It’s ‘hub and spokes’ system created prisons whereby the Border Agency had a permanent residence and people could be ‘processed’ more efficiently. Following prison sentences, if not already deported, people would be detained in Immigration Removal Centres indefinitely until deportation or an effective legal appeal (rarely succeeding in the case of those that have been categorised as criminals). Detention centres are nearly all run for profit by private companies and have been extensively researched by Corporate Watch, revealing widespread abuse.

The prison system itself was re-designed to enable greater numbers of deportations. It’s ‘hub and spokes’ system created prisons whereby the Border Agency had a permanent residence and people could be ‘processed’ more efficiently. Following prison sentences, if not already deported, people would be detained in Immigration Removal Centres indefinitely until deportation or an effective legal appeal (rarely succeeding in the case of those that have been categorised as criminals). Detention centres are nearly all run for profit by private companies and have been extensively researched by Corporate Watch, revealing widespread abuse.

There were 9,340 (1,585 remand, 6,892 sentenced and 863 non-criminal) foreign nationals held in custody and HMPPS-operated Immigration Removal Centres (IRCs) as at 31 December 2017; representing 11% of the total prison population.

The Migration Observatory reported that the UK removed 6171 foreign national prisoners in 2016, a small number of the 39,626 people who were removed from the UK or who departed voluntarily after the initiation of removal. Nationals of India, Pakistan and Romania made up 32% of the total.

Many foreign national prisoners are from ethnic minorities with colonial ties to the UK. A large number are also east Europeans with marginalised white ethnicities who are subject to ‘xeno-racism’. For example, more Albanians were expelled than any other nationality in 2015. The most common nationalities after British Nationals in prisons are Polish (9% of the FNO prison population), Irish (8%), Albanian (8%), Romanian (7%) and Jamaican (5%).

Experiences of Foreign National Prisoners

According to research by Sarah Turnbull and Ines Hasselberg from the University of Oxford, foreign nationals are liable to spend more time in confinement than their British Counterparts. More specifically, they are very likely to be imprisoned on remand while awaiting trial and sentencing, given longer custodial sentences, refused re-categorisation to more open prison conditions, detained after sentence under immigration powers and refused bail from immigration detention on account of their previous conviction(s).

Foreign national prisoners are also more likely to experience social isolation within prison due to language barriers and other factors and are less likely to have outside social support to help them survive prison. Research has shown foreign national prisoners are also more vulnerable to suicide and self-harm. One example is 26-year-old Darius Lasinskas, who killed themselves at HMP Huntercombe in 2016, who was anxious about his deportation to a Lithuanian prison. In 2015, the Institute for Race Relations produced a harrowing report detailing deaths of foreign national prisoners and the complex, tragic and unjust stories of those who died in the British prison system.

Deportations

Deportations are yet another weapon in the arsenal of social control. People are regularly deported to Nigeria on commercial flights, as well as on charter flights every two months. Charter flights involve the commissioning of a dedicated plane to remove people in larger numbers. Profiting from these flights to Nigeria is Titan Airways. During one flight in 2016, one deportee who was clearly unfit to fly, having survived a brain operation, was taken to the plane in an ambulance.

Deportations are yet another weapon in the arsenal of social control. People are regularly deported to Nigeria on commercial flights, as well as on charter flights every two months. Charter flights involve the commissioning of a dedicated plane to remove people in larger numbers. Profiting from these flights to Nigeria is Titan Airways. During one flight in 2016, one deportee who was clearly unfit to fly, having survived a brain operation, was taken to the plane in an ambulance.

Testimony from a refugee detained in Yarl’s Wood Detention Centre read “I am a lesbian which is not ok in Nigeria… I had to leave Nigeria because I was scared of my husband. I was forced to marry him in an arranged marriage… My ex-husband said he knows I am being deported next week. He is waiting for me. He is planning to kill me”. Nigeria’s anti-LGBT codes were first introduced under the British empire. Now homosexual acts are punishable by up to 14 years in jail in the country.

Another detainee talking about charter flights wrote that “Many atrocities have been committed through these flights. Mothers have been separated from their children who are unfortunate to be born to Nigerian parents as the government do not fight for their rights. Instead, they are part of the thousands that the government of Nigeria has sold off to the British government. Welcome back to the slave trade!!!!”

Mitie recently took over from Tascor as the company contracted by the Home Office to deport thousands of people each year.

Criminalisation and the strengthening of Policing in the Border Regime

Melanie Griffiths describes the shifting political landscape of making more people criminal and (certain) people more foreign. Key actors in this process are the police and even prison officers, whose roles now include checking citizenship status. Corporate Watch’s report on the Hostile Environment talks about attempts to turn the UK into a nation of border cops.

A key initiative widening the net of what counts as criminal is Operation Nexus; a pilot scheme that started in London in October 2012 that is rolling out across the UK. The Home Office says that the overarching aim of Operation Nexus is to improve the management of foreign nationals and foreign national offenders with a focus on strengthening cross-organisational working between the Home Office and police.

A key initiative widening the net of what counts as criminal is Operation Nexus; a pilot scheme that started in London in October 2012 that is rolling out across the UK. The Home Office says that the overarching aim of Operation Nexus is to improve the management of foreign nationals and foreign national offenders with a focus on strengthening cross-organisational working between the Home Office and police.

In this scheme, Metropolitan Police are required to pass details of all “foreign nationals or suspected foreign nationals” they “encounter or arrest” to a central Home Office unit called the Command and Control Unit (CCU). Staff in this central unit then check their details against the Home Office’s databases, primarily the main Case Information Database (CID). If there is a “match” with a known “immigration offender”, the case is then referred to several ICE Immigration Officers (IOs) who are embedded as “police liaison officers” in a number of area “hub” police stations for this purpose. A group of other IOs and police work together in a dedicated Joint Operations Centre (JOC). Targeted individuals may then become at risk of being deported.

Evidence is gathered to show that deportation is ‘conducive to the public good’. A disturbing fact about Operation Nexus is that court-admissible evidence is not necessary. A broad range of material is used to ascertain criminal ‘conduct’ or ‘character’ based on a motley collection of allegations, anonymous sources, circumstantial evidence, hearsay and more.

Operation Nexus is presented as targeting ‘high harm’ foreign national offenders, however, it has effectively widened its own net. Griffiths describes this: ‘Nexus does more than simply increase the detection of Foreign Criminals, then, it expands the definition and membership of the category itself’.

New offences have also been created under the UK Government’s Hostile Environment initiative. Under the Immigration Act 2016 new offences include: “illegal working”, whereby the maximum penalty is six months in prison plus an unlimited fine. In addition, any earnings from “illegal work” can be seized. If the prosecution can show that an employer knew or had “reasonable grounds to believe” that an employee did not have a right to work they can face up to five years in prison. Likewise, renting to someone who you have “reason to believe” is without papers can also bring a maximum five year prison sentence.

Resisting Conditional Solidarity and the Good Migrant/Bad Migrant narrative

By becoming criminals, or becoming criminalised, human beings become fundamentally dehumanised. The violent process of imprisonment, detention and deportation becomes deserved and justified within popular opinion because people have transgressed legality or potentially caused harm to others. Prisons are sanctified as natural, normal and necessary in order to discipline, punish and deal with ‘problematic’ people. Criminalising ‘foreigners’ creates effortless popular support for state violence.

Likewise, the distinction between ‘Good/Deserving Migrant’ and ‘Bad/Underserving Migrant’ or the ‘vulnerable Refugee’, can reinforce the acceptance of incarceration, deportations and the border regime for those that fall into the criminal justice system’s net.

In her paper on Foreign National Prisoners, Griffiths shared that journalists have told her that data on extreme lengths of detention are not newsworthy if detainees have criminal records. If charities, NGOs or even grassroots organisers depend on discourses of innocence without critically interacting with the complexities of the criminal justice system, racist targeting, marginality and precarity, our efforts are doomed to fail in supporting other human beings survive broader systems of oppression and state repression. William Calethes describes how racialised punishment persists over time because it provides political, social and economic stability required for continued white elite capital accumulation. Our solidarity cannot be conditional in a broader context of state violence and racial capitalism.

Resisting the Prison Industrial Complex Globally

Banner at Yarl’s Wood Demonstration

The prison industrial complex is a global beast. Penal power is playing an increasing role in global migration. The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund is just one example of how the capitalist resources of Britain and the west are leveraging neocolonialist projects aimed at strengthening state forces, who use policing and prisons as tools for social control. All the while, private corporations profit from prison construction, prison labour and the border regime as human bodies are treated as mere commodities for exploitation.

It is clear that the Nigeria Prison project is not going to prevent human rights abuses within its walls. Nor will an increase in capacity by adding one new prison wing effectively reduce overcrowding. Studies from the UK and elsewhere have shown building new prisons only leads to more overcrowding. As the British Government continues working on its own £1.3 billion prison expansion programme for England and Wales, we see how states continue to invest in infrastructure for repression while failing to solve any social or economic problems by caging human beings.