Greek debt: what they don’t tell you

[responsivevoice_button]

Over the past few weeks Alexander Stubb, Prime Minister of Finland, amongst others in Merkel’s camp have been adamant that Greek debt cancellation is out of the question. Whether this proves true or not will depend on whether such statements fall within the realpolitik of the euro crisis management thus far: “When it becomes serious, you have to lie”, as current Commission president and former Eurogroup president Jean Claude Juncker explained to the public in May 2011.

This is important as it concerns the most common lie about the reason for the Troika’s interventions in the first place. With Syriza’s election, the voices who maintain the bailouts are a signal of solidarity from northern Europe to south have grown louder and arguably more vicious.

However, let’s take a step back and see what has happened. Not so long ago one of the most powerful US think tanks, the Council on Foreign Relations, declared that “the IMF’s growth forecasts for Ukraine and Greece [are interpreted] not as forecasts at all, but rather as assumptions necessary to justify the IMF’s interventions”. Following the stir the nascent Greek government caused from day one regarding the EU sanctions against Russia, it is not a surprise that tensions in Europe are already running high. Now why might the IMF have considered it necessary to justify an intervention in Greece?

Each time a Troika functionary dictates why Greece (or any other country) needs to adhere to the harsh bailout conditions, it brings to mind the executive director on the board of the IMF, Karin Lissakers, calling a spade a spade: “The Fund is acting as enforcer of the banks’ loan contracts”. This was in 1983. Numerous bailouts were implemented since, so that countries would not default on their foreign lenders.

The ΙΜF’s European counterpart thinks exactly the same: the head of the European Stability Mechanism fund, Klaus Regling, leaves no doubt as to how the bailout system works: “What we in Europe are doing right now is precisely what the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been doing all over the world for decades without ever losing money. IMF loans are tied to the condition that the country overhauls its economy, as are ours.”

Among the cacophony of commentary about the Greek debt, it is important to reflect on why the bailouts originated. The proof is in the pudding: all but approximately 11% of the bailout money has ended up creditors’ pockets.

It is not however solely Greece’s original reckless lenders that have been saved: Greece has been using Troika bailout money to repay the vultures that had manoeuvred their way into escaping the forced cancellation in 2012. With repayments on PSI holdout bonds due in March 2015, this precedent seems set to continue.

Stephanie Kretz, a private banking investment strategist at Swiss bank, Lombard Odier, repeats something that is oft and openly admitted about the original motives for the bailouts: “Germany, by lending money to the peripheral countries, is trying to prevent its fragile and leveraged banks from getting hit, effectively orchestrating a back-door recapitalisation of its own banking system”.

Senior German officials were equally frank; Peter Böfinger, an economic advisor to the German federal government, admits that the bailouts “are first and foremost not about the problem countries, but about our own banks, which hold high amounts of credit there.” There is no surprise as to why the bailouts originated, yet simple myths still dominate discussion.

Between 2008 and 2011 Germany, France, Netherlands, Austria, and Belgium approved astronomical sums to bolster their financial sectors, equalling 25%, 18%, 52%, 31% and 97% respectively of these countries’ 2011 GDP. Besides obvious embarrassments bearing names such as HypoReal Estate, Dexia, or the Landesbanken, a clear imperative of the huge injections was to minimize losses on investments into sovereign bonds. “It is an open secret”, explains Deutsche Bank CEO Josef Ackerman, “that numerous European banks would not survive having to revalue sovereign debt held on the banking book at market levels.”

Contrary to the officials’ whining, the bailouts so far were good for those who invested in them. Take for example the central banks: even though central banks eventually decided to forfeit their profits made on those Greek investments, due to political pressure, until that decision “the Finnish central bank contributed 227 million euros to the Finnish budget as a result of profits made on the Greek, Spanish and Portuguese government bonds it holds, 40 million euros more than it made in 2011. This year [2013], the profit should rise to 360 million”. Martti Salmi, of Finland’s finance ministry, noted that “As an unintentional consequence of the crisis, Finland has benefited enormously. We have not lost a cent so far, the same as for Germany.” Ultimately this means that the Troika is making good money out of the bailouts, which are everything but a ‘helping hand’ for ‘debt-stricken’ countries.

The circularity of the debt mechanism just described, is absurd as it is starkly ruthless. In 2014, almost 17 billion euros needed to be repaid by the Greek government to eurozone officially held debts. Greece borrowed this money from the Troika, under the condition that several more severe austerity packages were pushed through. Once the neoliberal restructuring was complete, the profits the ECB and Eurosystem made, an amount equivalent to the income on the portfolio accruing to national central banks, were repatriated to Greece.

The vicious cycle of debt payments is thus more pronounced now that the majority of Greek debt is held by the official sector. The debt restructuring in 2012 changed the ownership profile of public debt rendering the Troika the largest creditors of the government.

Are all those who heralded it a success at the time, surprised by the outcome today? It is not a new occurrence that debt restructuring utterly failed to provide debt relief: Evidence from past experiences of 73 countries defaulting and renegotiating with private creditors shows that average creditor losses may have been in the realm of 40%, and may have taken seven years to resolve, yet debt relief was minimal.1 Other examples show that large bondholder haircuts can even correspond to increased debt burdens.2

The transformation of the Greek public debt into mostly officially held debt is an important leverage point for the new government of Syriza. With scaremongering surrounding the large repayment in the summer 2015 towards the ECB, let’s bring to mind the words of a Senior Advisor to Deutsche Bank that “Greece will not default on the troika because the troika is paying themselves”.

Following the recruitment by the new Greek finance minister,Yiannis Varoufakis, of Lazard to enter and help advise on the issue of public debt, the results of the negotiations await to be seen. Lazard is a member of the IIF, the private banking lobby that advised the Papademos government on the 2012 debt restructuring. This effectively led to the Greek tax payer borrowing millions to pay for its advice (25 million) on how its pension funds should be rinsed.

There is a growing chorus of voices calling for debt reduction and an end to austerity. The voice of Krugman has been joined by almost daily commentary by the likes of Stiglitz, by several other economists of similar clout, by discussions in the FT, Bloomberg and Reuters, all writing on variations of the same theme: in favour of Merkel backing down, and for some new arrangement to be found. The gist of what is said has been completely obvious from the start: the debt is unsustainable, the bailout loans benefited the banks, austerity has strangled the economy, and shattered the society.

The new political compromise across Europe has yet to be found. What is worth drawing our attention to however, is that whilst the Greek debt fiasco continues to dominate discussions, the central issues regarding debts and deficits in the euro and the EU remain unchallenged. Syriza, despite throwing a spanner into the Troika’s works by laying out a plan that revokes the Troika’s conditions – such as the plans for increasing minimum wage – remains firm on its commitment for balanced budgets.

It seems these will be aimed to be achieved within the strict limits of the fiscal compact – the permanent austerity treaty that is the cornerstone of the new EU governance rules. It is essentially the memorandum that Merkel instituted for everyone. The conditions are so stringent, expansionary fiscal policy has been effectively outlawed. The OECD has calculated that “to stay within this rule for every year from 2014 to 2023, Greece will have to maintain a primary budget surplus of about 9% of GDP, Italy and Portugal about 6% of GDP, and Ireland and Spain about 3.5% of GDP.”

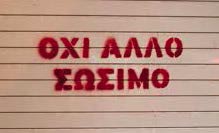

In this respect, and although much remains to be seen in terms of the configuration of power balances in the upcoming negotiations, it is the overall neoliberal straightjacket across Europe, that one can hope to be contested, and for these illegitimate debts to once and for all cancelled, and not smuggled away into the future.

The recently published critical guide to the crisis by Corporate Watch: False Dilemmas, covers the why, what and how of the crisis, providing in depth analysis to the get to grips with what really has been happening. It provides details of what the authorities have done, numerous arguments to debunk austerity, tools for debt resistance, and inspiration from social movements. It is available for purchase here.

This article was originally published on the 9th February with Open Democracy.

References

1Wright, Mark (2011) “Restructuring Sovereign Debts with Private Sector Creditors: Theory and Practice” in C. Braga and G. Vincelette (eds.) (2011) Sovereign Debt and the Financial Crisis: Will This Time Be Different?, World Bank

2Zettelmeyer, Jeromin (2012) “How to do a Sovereign Debt restructuring in the euro zone: Lessons from Emerging Market Crises,” paper prepared for Resolving the European Debt Crisis, a conference Page 33 of 39