Delancey: tax-haven Tories devouring neighbourhoods

Delancey is a property developer involved in some of London’s highest profile gentrification schemes, including Elephant and Castle shopping centre and Stratford’s former Olympic Village. And now it’s spreading across the UK, with big developments planned in Leeds, Manchester, Portsmouth and Glasgow.

Delancey is run by old-Etonian Jamie Ritblat, son of a powerful family of property tycoons who are also major funders of the Conservative Party and other right-wing causes. It has financial backing from billionaires including George Soros and the dictatorship of Qatar.

This is the story of UK property profiteering in a nutshell. The old British elites meet new global investors, united through a complex web of letterbox companies registered in offshore tax havens. While their deals are eagerly facilitated by politicians from all parties.

A few key points about the company:

- Olympic Village. Delancey is best known for its partnership with the Qatari royal family to buy East London’s former Olympic Village and turn it into private rental flats. The land was sold at a loss by the UK government. At the time of sale, Sir John Ritblat (Jamie’s father) was a member of the government’s Olympics “oversight” committee.

- Elephant One. In its earlier Elephant & Castle tower blocks development, Delancey managed to get out of all affordable housing commitments for a payment of just £1 million.

- Most Delancey schemes are partnerships with other investors, whose identities are often hidden behind offshore funds. But a few regular partners have come to light, including: billionaire speculator George Soros, the ruling family of the dictatorship of Qatar, Royal Bank of Scotland, and pension funds from Canada and the Netherlands.

- Delancey and Jamie Ritblat have funded the Conservative party to the tune of at least £345,000. The Ritblat family also support a range of right-wing “neo-conservative” think tanks.

- The Ritblats have a powerful network of connections in the UK’s political and cultural elites. They sponsor and sit on the boards of institutions including Kings College, the Tate Gallery, and the Royal Albert Hall.

- Recent Delancey’s schemes involve its joint venture company “Get Living”, a “build to rent” corporate landlord. Beyond London, Get Living is planning massive new rental apartment developments in Leeds, Glasgow and Manchester.

You can click the links below to jump to the following sections:

- Company structure: a network of offshore letterboxes

- Get Living: Delancey’s new “build to rent” corporate landlord

- Who profits?

- Who runs it? The Ritblat family and friends, and their cultural connections

- The Ritblats’ right-wing politicking

- A few notorious deals: Mapeley scandal, Olympic village, Elephant One

- Behind Delancey: meet the investors, from Soros and Qatar to Canadian pensioners

How Delancey works

Delancey was founded in the 1995 by Jamie Ritblat, an Eton-educated Conservative donor born to wealth and power. Jamie is the son of Sir John Ritblat, a well-known property tycoon worth an estimated £234m, who for decades ran Britain’s second biggest property company, British Land. Jamie learnt the ropes at his father’s company before striking out on his own with Delancey.

Delancey describes itself as a property investment “advisor”. That is, its developments don’t just use the company’s own capital, but bring in other investors from across the world.

In the last two decades, Delancey “has acquired, developed, managed and sold over £20bn of property” through its various funds and companies. It bulked up during the 2008 financial crisis – taking advantage of the dip in property prices to buy up ‘distressed’ assets from the Royal Bank of Scotland, and to take over another major London development company, Minerva.

The funds Delancey “advises” own buildings across London and the UK. Its investments reflect the big trends in UK property speculation: from corporate office developments in the 1990s and early 2000s, to today’s focus on “Build to Rent” housing. Delancey’s latest major venture is its Get Living rented apartment complexes (see below).

Delancey also has an educational sideline: a chain of elite private schools called Alpha Plus.

Alpha Plus promotional picture from Delancey’s website

Company structure: a network of offshore letterboxes ..

Delancey’s plush London headquarters are in Mayfair’s Berkeley Square. But the money is moved around a complex web of companies, many of them registered offshore in the British Virgin Islands tax haven.

In the early days, Delancey was a public company (PLC) listed on the stock exchange. But in 2001 Jamie Ritblat bought out the shares to turn it private – with the backing of his major investors George Soros, John Ritblat, and the Royal Bank of Scotland (which reportedly helped out with a £170 million loan).

As a private firm, the parent company for many years was Delancey Real Estate Partners (DREP), which is registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) tax haven. But in 2018, Delancey was restructured. DREP is now legally a subsidiary of another company called Cortx Holdings Limited (CHL), which until 8 May 2019 was called Cortx 1. Unlike DREP, Cortx is registered in the UK. Cortx has one controlling shareholder: Jamie Ritblat.

But Cortx’s latest accounts show assets of just £35 million, while the Delancey property empire is worth billions. How does this work?

Investment funds

First of all, Delancey sets up and manages investment funds into which different investors pool their money. These often have bland names – such as DV3, DV4, etc. As well as the initial investments, these funds can be ‘geared up’ by borrowing more money from banks and other lenders. Delancey then gets paid management fees for running these funds and “advising” them on property deals.

It’s not easy to find out who are the investors in Delancey’s funds. They are typically registered in offshore locations with minimal accounting transparency, allowing investors to remain anonymous.

Back in 2009 the Information Commissioner ruled on a “freedom of information” request from a campaigner asking for information on Delancey’s involvement in developments in Bury St Edmunds. After a battle, the local council finally released a letter from Ritblat naming some of the investors in the DV3 fund. As Private Eye has reported, these included Soros, the Royal Bank of Scotland, and various insurers and pension funds. Separately, it emerged that another investor was Conservative minister Andrew Mitchell.

It is not clear which funds remain active. The DV4 fund certainly is: it is described as an “open-ended” fund without a fixed lifespan, and continues to make new investments after more than a decade in operation. But there is no public information on who its current investors are.

Development companies

When Delancey has secured a site for development, it will often set up a specific company with its partners to manage this deal. These may be structured as “Limited Liability Partnerships” (LLPs) and, again, may involve offshore tax havens.

For example, for its Elephant and Castle shopping centre development Delancey has set up an offshore company called Elephant and Castle Properties Co Limited, based in the British Virgin Islands. This in turn is owned by Elephant and Castle LLP, a limited liability partnership registered in the UK. And this has a number of partners:

- DOOR S.L.P – a Jersey registered collaboration between Delancey’s DV4 fund and Oxford Properties, part of Canadian pension fund OMERS.

- Stichting Depository APG Strategic Real Estate Pool – a vehicle of the Dutch pension fund APG, registered in the Netherlands.

- Qatari Diar Real Estate Holding Company – a fund owned by the government of Qatar.

- QD UK Holdings Limited Partnership – a Scottish Limited Partnership vehicle also owned by Qatar Diar Real Estate Investment Company Q.S.C

- Kintyre Corp – a property investment vehicle registered in Panama, named in the leaked Panama Papers. (NB: it is not clear whether this vehicle is connected to the German developer Kintyre, which opened a London office in 2016.)

We look in more detail at some of these partners below.

Get Living site at former Olympic village, from Delancey’s website

Get Living

Delancey’s newest business focus is the booming “build to rent” property sector. Build-to-rent schemes are typically big developments with hundreds of flats in shiny tower blocks – but rather than selling them on to private buyers, the developer rents them out, becoming a corporate landlord. (See our recent profile of Grainger PLC for much more on this trend.)

Delancey first set up Get Living to rent flats in its East Village development on the former Stratford Olympics site (see below). It was then expanded to incorporate rental units at Elephant One (see below), and is now lined up for the Elephant and Castle shopping centre scheme too.

But these London developments are just the start of Get Living’s ambitions. The company says it has a current “development pipeline” of around 4,400 homes, and aims to build a portfolio of 12,500 properties. Outside London, it has acquired 800 homes in Middlewood Locks in Manchester, and lined up big sites at Globe Road in Leeds and in the centre of Glasgow.

The latter is a £200 million development with 727 flats for rent that will be “Scotland’s largest build to rent scheme to date” which will “completely overhaul a key area of Glasgow”. Work on the first phase of the development is expected to start in 2019, subject to building warrant.

The rent charged by Get Living does not come cheap. In Delancey’s Elephant One development, student rooms In Porchester House start at £279 per week for a ‘Classic’ room, or £349 for a ‘Supreme’. Private rented units are being advertised starting at £1,841 per month for a 1-bed flat.

Like other Delancey schemes, Get Living is a joint venture involving a number of regular investors. Again, the initial partners were Qatari Diar, and the Dutch pension fund APG. In 2018, Delancey also brought in another big investor – Oxford Properties, the property investment business of Canada’s Ontario pension fund (OMERS). They set up a new joint venture company called Delancey Oxford Residential (DOOR), owned jointly by Delancey’s DV4 fund and Oxford Properties, with stated plans to invest £600 million in UK residential property.

After Oxford Properties got involved, Delancey registered a new company called Get Living Limited. Its partners were:

- DOOR (Delancey DV4 and Oxford Properties): 39%

- APG: 39%

- Qatari Diar: 22%

And in another classic tax avoidance move, Get Living is now converting to become a “Real Estate Investment Trust” or REIT. This is a fully legal tax-dodging structure introduced into the UK in 2007, after concerted lobbying by the property industry. Unlike other companies, REITs are exempt from paying corporation tax.

The requirements for a company to register as a REIT are that they focus on property investment, distribute 90% of their profits to investors every year, and are listed on a recognised stock exchange. To meet this last requirement, in November 2018 Get Living re-registered as Get Living PLC, and was listed to sell shares on the Guernsey Stock Exchange.

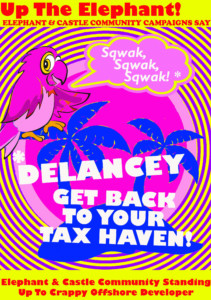

Graffiti against Delancey development at Elephant & Castle

Who profits?

Because of the complex and secretive corporate structure outlined above, it is hard to trace how much profit Delancey’s developments make – or whose hands those profits end up in.

Cortx, Delancey’s new legal parent company, reported a turnover of £18.6m in 2018 – “advisory fees” from its funds and investment vehicles. However, the company’s accounts claim it made a loss of £4.6m, after paying out £22 million in “administrative expenses”.

These administrative expenses include: £1.2 million in interest and finance costs; £14.5 million in salaries to 55 staff; and £4.6 million in payments to its directors. Cortx has just two directors: Jamie Ritblat and Paul Goswell. So although we don’t know who was paid what, we know that between them they pocketed £4.6 million in 2018.i

As the company registered a loss in 2018, it didn’t pay out any dividend to its owner – also Jamie Ritblat. But with his share of the £4.6 million directors’ pay, that shouldn’t have bothered him much.

However, we shouldn’t get too fixated on Cortx’s figures. They don’t begin to capture the vast amounts of capital flowing in and out of Delancey’s multi-billion pound property deals, through a misty archipelago of funds and offshore vehicles.

For example, a business media article in August 2018 reported that Delancey’s DV4 fund had sold £1.2 billion worth of property in the previous 12 months. There is no way of knowing how much profit Delancey’s investors made on those sales.

Who runs it? The Ritblats, their entourage, and their cultural power

All Delancey’s network of companies trace back to one man: Jamie Ritblat. And Jamie got where he is today thanks to the support of his property tycoon father Sir John Ritblat, who continues to pull strings for his son’s business.

But the Ritblats, and the other directors around them, aren’t just businessmen. They are also heavyweight players in Britain’s elite cultural scene, sponsoring and sitting as directors on numerous national institutions. Of course this helps them keep up an impressive network of powerful connections which are great for business too.

The boss: Jamie Ritblat

Jamie Ritblat is Delancey’s founder and CEO. He has a London address at 24 St Petersburgh Place in Bayswater. He also built and owns a fake 18th Century stately home in Winchcombe in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds.

When he’s not busy donating to the Tories, stashing millions out of sight of the taxman, or getting plebs to serve him in his mansion, Jamie lends his name and elitist credentials to prestigious London art institutions and universities. In the past, he’s been a member of Kings College London’s College Council and member of the Southbank Centre’s Board of Governors. He also helps out other property financiers: he is non-executive chairperson of private equity real estate firm Mitheridge Capital Management.

But, according to his bio on the Mitheridge website, he has now stepped down from his voluntary roles except for one: he remains an “active Trustee” of the Bathurst Estate – an 8,000-acre estate in Gloucestershire where he helps out the Earl Bathurst and the rest of his ‘barmy’, hunting enthusiast family.

Sir John Ritblat (wikimedia commons)

Big Daddy: Sir John Ritblat

Ritblat senior has provided backing, advice and crucial connections through the years. After stepping down from British Land in 2007, he became chair of Delancey’s advisory board.

Now formally retired, Sir John and his wife Lady Jill have been directors or trustees of many top arts, education and sporting institutions. Their current and former positions include the boards of the Wallace Collection, Royal Academy of Music, the Design Museum, the Royal College of Art and the London Business School.

They are also big patrons of the arts themselves. John Ritblat has a room named after him at the British Library, “The Sir John Ritblat Gallery, Treasures of The British Library”. Jill has donated her personal dress collection to the Victoria and Albert Museum, and they once bought a Damien Hirst as a birthday present for Jamie.

Despite now being an octogenarian, Sir John is still involved with the following organisations:

- Although now retired as a governor, he remains a Special Advisor to Dulwich College, his old school.

- Chairman, Falcon Prep School for Boys and Falcon Girls School.

- Hon Fellow and Hon Trustee of the Royal Academy of Music.

- Vice President of International Students’ House – where Nigel Carrington, the Vice Chancellor of University of the Arts also sits on the board.

- Honorary Fellow and Patron of the Council of The Royal Institution.

- President of British Ski & Snowboard.

- Ritblat and Delancey sponsor the British Alpine National Ski Championships

- Vice President of the Tennis & Rackets Association.

Colin Barry Wagman: Delancey director and close Ritblat family associate

A specialist in business strategy and tax planning, Colin is likely responsible for many of Delancey’s best offshore avoidance schemes. He is a director of Delancey (DREP) and of its subsidiaries Alpha Plus and Minerva. Until March 2018 he was Delancey’s vice chair and chief finance officer. He is also chairman of the City of London Group, which includes a number of brands providing finance to property owners and SMEs. He is a trustee of the Sir John Ritblat Family Foundation, which funds neo-conservative and Zionist organisations (see below).

Outside of finance and politics, Colin is a Trustee of the Bryanston Square Garden Trust, where he lives at number 7; and also, alongside Sir John Ritblat, of the Gold Standard Charitable Trust which pays for the education of underprivileged kids.

Stafford Lancaster: investment director

Stafford often appears as a spokesperson for Delancey in the media, including on the Elephant and Castle project. He is invariably described as “investment director at Delancey”, where he has worked since 2000. According to one online bio, he has “particular responsibility for Delancey’s residential investment and educational portfolios”, and “his role is to oversee and implement the company’s existing, ongoing and future investment and development strategies, including the Elephant & Castle Town Centre redevelopment.”

He chairs the Reading Real Estate Foundation, a charity set up ‘to provide support for real estate and planning education’ at the University of Reading’ where he studied land management.

Paul Jonathon Goswell: Delancey managing director

The only other director listed alongside Jamie Ritblat of Delancey’s new parent company Cortx. He has a number of positions in London institutions. He is an independent member of the King’s College Council, and sits on the Development Board of the Royal Albert Hall.

Stuart Corbyn: chairman of Get Living

Until 2008 Corbyn was chief executive of the Cadogan estate, the property holdings of the Earl of Cadogan, one of London’s biggest landowners who basically owns Chelsea. Corbyn has also been president of the British Property Federation. He played a leading role in Delancey’s Olympic deal with the Qataris, chairing the initial joint venture company they set up.

With his aristocratic Chelsea connections alongside his Ritblat links, Corbyn is another paid up member of the London elite who has held directorships of institutions such as the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Hospital Chelsea, Royal Parks Foundation, Chelsea Festival, and Somerset House Trust. He is a member of the council of the Royal Albert Hall, “sitting on the Fabric and Seat Rate Committees”.

Cartoon thanks to Southwark Notes

The Ritblats’ right wing politicking

The Ritblat family don’t just have the power to shape our built environment and our cultural life, they also dabble in political influencing. Delancey is a major funder of the Conservative party. Sir John Ritblat uses his “family foundation” and other charitable trusts to back think-tanks spreading neo-conservative, war-mongering ideas, and an arch capitalist pro-Brexit lobby group.

- Conservative Party. Delancey as a company makes regular donations to the Conservative party. Since 2011, the company has donated £335,000 – according to declarations in annual accounts.ii Jamie Ritblat also made a personal donation of £10,000 in 2015. Sir John Ritblat has not reported any cash donations to the party, but he was widely reported sitting with former prime minister David Cameron at a Tory party fundraiser.

- Henry Jackson Society. This right-wing think tank is described in a study by Spinwatch as a leading exponent of neoconservatism in the UK today: “grounded in a transatlantic tradition deeply influenced by Islamophobia and an open embrace of the ‘War on Terror’.” It is one of the main regular beneficiaries of the Sir John Ritblat Family Foundation. One recent Henry Jackson Society project is an organisation called Student Rights, which presents itself as “against extremism” and promoting “free speech” on campuses – but is accused by the National Union of Students of “fuelling Islamophobia”. Its director Raheem Kassam went on to become editor of “alt right” news portal Breitbart London.

- Weizmann UK. Sir John Ritblat is vice president of this UK foundation and supports it through his charitable trusts. Set up to support the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, in recent years Weizmann UK has taken a political stance in trying to fight boycotts against Israeli academic and cultural institutions.

- Open Europe. Right wing think tank, linked to neoconservative movements, that pushes for “economic liberalisation” in Europe. Described by the Economist as “the Eurosceptic group that controls British coverage of the EU”. Sir John has donated through his Family Foundation, and is listed as a “supporter” on Open Europe’s website.

A few infamous Delancey deals

The Mapeley scandal

Along with long-time backer Soros, Delancey was involved in one of the most notorious UK property scandals of the early 2000s: when no less an institution than the Inland Revenue sold its own offices to an offshore consortium based in the tax haven of Bermuda.

The deal, one of the most brazen examples of the last Labour government’s PFI mania, is called STEPS: “Strategic Transfer of the Estate to the Private Sector”. In 2001, three government departments – the Inland Revenue, HM Revenue and Customs, and the Valuation Office Agency – signed a contract selling their office buildings and other property to a private company for £220 million. The company then leased the buildings back to the government for 20 years, for a fee averaging £170 million per year. Altogether, the freeholds and leaseholds on 698 buildings were handed over.

The company was called Mapeley STEPS. It was a joint venture specially set up for the deal, and registered in Bermuda. It was owned by three partners: Soros Real Estate Partners (42.5%), Fortress Investment Group (42.5%), with Delancey as the junior partner holding 15%.

The government claimed it would save millions in property maintenance over the deal’s lifetime. But the deal became a national scandal when, in 2002, the Inland Revenue was forced to come clean about the buildings being sold to a company registered in a tax haven. It was reported that the Soros-Fortress-Delancey partnership could save some £170 million in tax through this offshore structure.

Olympic Village

London’s 2012 Olympic Games involved building an “Olympic Village” with athletes’ accommodation in Stratford, East London. While parts of the site were empty, others involved demolishing 450 homes on the Clays Lane Estate. The site was owned a quango called the Olympic Development Authority (ODA), which reportedly spent £1.2 billion on building the Olympic Village.

The ODA lined up developers to take over after the games. Part of the site, with 1,379 properties, was sold for “affordable housing” to a consortium called Triathlon Homes. The other 1,439 homes, known as “East Village”, were sold in 2011 to the partnership of Delancey and Qatari Diar. The Delancey-Qatar partnership also got six neighbouring development plots with planning permission for 2,000 more apartments.

All this cost them £557 million. With Triathlon paying £268 million for their bit, overall the UK government lost £275 million on the deal.

After widespread fears about the games’ costs going over budget, the government had set up an Olympics Oversight Committee of “business experts”. The committee’s remit specifically included the costs and finances of the Olympics development site. Its chairman was none other than Sir John Ritblat.

The Daily Mail has claimed Delancey and the Qataris could make as much as £1 billion on the Olympics deal. The bulk of the East Village apartments are now rented out by Delancey’s joint venture “build to rent” company Get Living. The village itself is an example of a pseudo public space that is basically fully privatised, patrolled by a private security army who move on anyone trying to sleep on the streets, or even set up a camera on a tripod without permission.

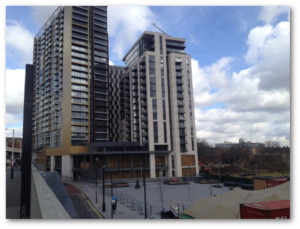

Elephant One development, from 35% campaign

Elephant One – how Delancey avoided any affordable housing

Delancey’s first development in the Elephant and Castle area was a “mixed use” scheme called Elephant One, next door to the Elephant and Castle shopping centre it is now planning to demolish. Completed in 2017, Elephant One features shops and tower blocks with 272 student rooms and 374 private residences managed by Get Living.

Research by the 35% campaign has revealed Delancey’s “dirty tricks” in the development – including how it managed to get out of commitments to build any affordable housing.

Summed up, Elephant One was a classic story of “development creep”: over the several years between first getting planning approval and the actual build, ever more profitable units were added into the scheme, while the promised “affordable” units or community facilities disappeared.

The once public land was originally sold by Southwark Council to Sir John Ritblat’s British Land. Then, in 2006, it was sold again to an Isle of Man registered company called Eadon Estates for £8.5 million. Eadon Estates was a joint venture owned by Delancey’s DV4 fund and another developer called Oakmayne. The development was originally called Oakmayne Plaza, then renamed Tribeca Square, before finally becoming Elephant One.

Then between 2006 and 2011 Delancey resold the land to itself twice via offshore companies, each time inflating the price considerably. The land’s value went from £8.5m in 2006, to £18m in 2007, then £40m in 2011.

And over this period Delancey submitted several new planning applications, using revised figures to change its “viability assessments”. These are the crucial documents in which developers argue they cannot provide the expected amount of affordable housing and other commitments because otherwise they wouldn’t make a profit.

According to the 35% campaign:

Southwark later accidentally published the confidential viability assessment submitted to justify these concessions. It showed that £18m had been used as the land purchase cost – not the £8m originally paid. It also claimed that the completed residential flats would sell for an average of just £525 per square foot. Flats on Lendlease’s neighbouring Elephant Park are selling for an average of over £1,000 per square foot.

As a result, Delancey got away with dropping any plans for “affordable housing” at all:

Instead of affordable housing an in-lieu payment was agreed, amounting to just £1m and justified by the ‘exceptional cost’ to the developer of providing the market square and the basement access area – estimated to cost £12.5m. […] Delancey should normally have paid £52.7m under Southwark’s tariff for commuted affordable housing payments.

Then, in 2013, Delancey got even more concessions from the council. These included being allowed to raise the height of its buildings to include more market rent student flats, while promised “affordable retail units” were instead sold for a Sainsburys supermarket.

If anyone is wondering how Delancey manages to get away with all this, the answer is that Delancey is very well advised. Delancey has employed former deputy Council leader Kim Humphries as its adviser and representative. Indeed, Kim was deputy leader when the planning applications were approved […] He has been for hire as a freelance development consultant since he stepped down as deputy Council leader and Cabinet member for Housing.

Behind Delancey: meet the investors

Pic: George Soros (photo by Harald Dettenborn)

George Soros

One of Delancey’s major backers has long been hedge fund billionaire George Soros – the man famous for crashing Sterling in 1992’s “Black Monday” currency crisis, and more recently as bogeyman for conservative regimes due to his Open Society Foundation’s sponsorship of liberal causes. Soros’ “progressive” values have not stopped him being a key ally of the Ritblats, who themselves fund right-wing causes.

The relationship goes back at least to 1993. Soros decided to diversify some of his multi-billion winnings into the London property market. He partnered with Sir John Ritblat, investing £250 million in a joint fund with British Land targeting high profile commercial developments in the City.

When Ritblat junior went his own way with Delancey, Soros became his biggest investor – as well as acting as a “mentor”. In 1998, Soros “helped pump £127 million” into Delancey from his Quantum hedge fund – also based in the British Virgin Islands tax haven. By 2000, Soros reportedly owned 40% of the company, and was instrumental in backing Ritblat’s move to take it private in 2001. In 2005, Soros reportedly invested at least another £300 million in London premium office developments through Delancey funds.

Since Delancey went private, Soros’ investments with Delancey have been made through offshore funds which publish no information about their investors. One scrap of information came out in 2009, after a ruling by the Information Commissioner named Soros as one of the investors in the Delancey DV3 fund, which controlled a property portfolio worth an estimated £3 billion in 2008.

It is not possible to make any estimate of Soros’ present investments with Delancey. But Delancey’s current corporate brochure include Soros Real Estate Partners in its list of “partners and joint ventures”.

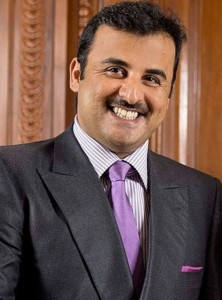

Qatari Royal Family

The small gulf state of Qatar is behind some of the UK’s biggest recent property developments. According to the BBC, “it is now said that Qatar owns more land in London than the Queen”. Those London holdings include the Shard, Canary Wharf, Harrods, the former US embassy in Grosvenor Square … and much more.

Qatar is an absolute monarchy, ruled since 1868 by the Al Thani family. It is only half the size of Wales, but sits on the world’s third largest reserves of natural gas.

In recent decades the Thanis have funnelled much of this wealth through their sovereign wealth fund, Qatari Investment Authority (QIA). This owns assets across the world, with a total value around $335 billion. The UK is currently the single largest target for their investments, with £35 billion invested.

The QIA has numerous subsidiary funds specialising in different asset classes. One of these is its real estate investment company Qatari Diar, which claims to own global property worth $35 billion. Qatari Diar is the main Qatari vehicle used for holding property in the UK, although other Qatari state companies also have separate holdings, as do individual members of the Thani family.

Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani, emir of Qatar

APG: enormous Dutch pension fund with a mixed “ethical” record

APG is one of the world’s biggest pension fund managers. Its total funds as of February 2019 were valued at €487 billion.

It is a subsidiary of the public sector pension fund ABP, which pools the pension contributions of government and education sector workers in the Netherlands. But it also now manages other pension assets as well. According to its website, it “works for over 21,000 employers, providing the pension for one in five families in the Netherlands (over 4.5 million participants).”

With its public sector focus, and a human and labour rights policy, campaigns have sometimes had successes in pushing APG to pull out from “unethical” investments. Its board includes a representative from the FNV trade union. In the past it has divested from Walmart, nuclear weapons and palm oil producing companies involved in deforestation. In January 2019, APG lost an appeal by trade unions against changes to military pensions. But these moves have not always succeeded: in 2014 APG was criticised for indirectly funding Israel settlements and again in 2018 ABP was criticised by environmental organisations for its investments in tar sands oil companies and pipelines.

Oxford Properties: Canadian pension fund with trade union representation

Oxford Properties is a global real estate company, which buys property across North America and Europe. It is based in Canada and wholly owned by a Canadian pension fund: the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS).

In 2018, Oxford Properties entered a new partnership with Delancey, setting up a joint venture company called DOOR, which has plans to invest at least £600 million in UK residential property. DOOR in turn is one of the main shareholders in the “Get Living” build-to-rent company (see details above).

OMERS is one of Canada’s biggest pension funds, with 496,000 members and assets of $97 billion in 2018. Like APG, its roots are in the public sector, it claims a commitment to “sustainable investing”, and has trade union representation on its board. The main union involved is the Ontario Public Sector Employees Union (OPSEU) which represents approximately 155,000 public sector across Ontario. They have shown willingness in the past to take on the OMERS pension fund over proposed changes and may not be aware of the damage their money is doing to communities in the UK.

Web page advertise Elephant & Castle properties for sale to Qatari investors

iThe accounts also state that the unnamed “highest paid director” received £1.95 million. This is a little mysterious, as there were only two directors and they received £4.6 million altogether.

iiDREP accounts declare £310,000 in donations between 2011 and 2017 https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/FC025976 ; Cortx (the new parent company) accounts show £25,000 in 2018 https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/10585680