The Home Office deportation drive against Channel-crossing migrants: a balance sheet

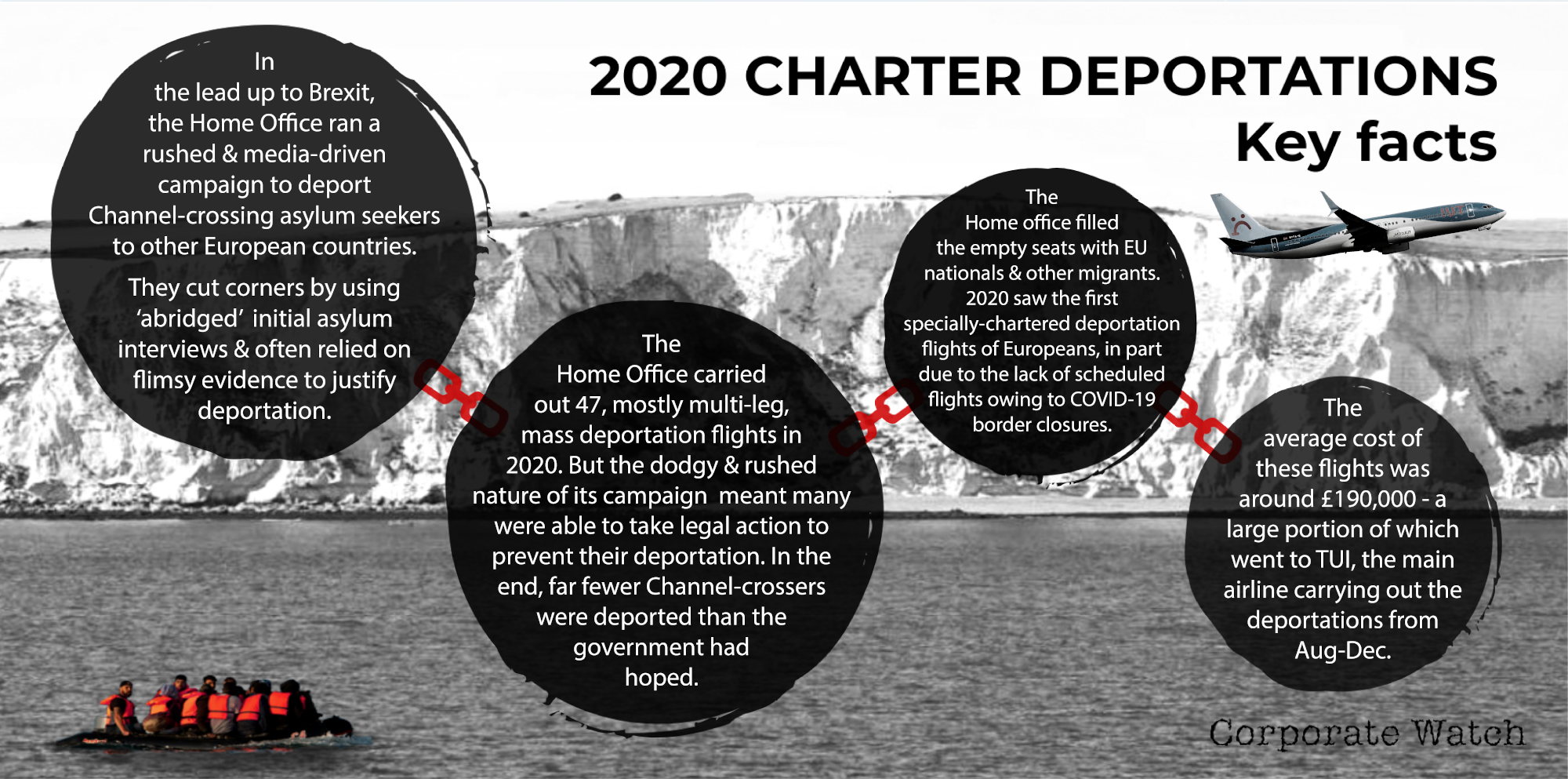

Between August and December 2020, in the run-up to Brexit, the UK Home Office carried out a rush of mass deportation charter flights. This was part of a media campaign to show the government was “taking back Britain’s borders” – against the menace of desperate refugees crossing the Channel in small boats.

Corporate Watch published a detailed report on one of the first flights, on 26 August, highlighting the abuse these refugees faced in the UK, and after they were dumped in Germany and France. We also profiled the airlines running these flights for the Home Office including Hi Fly, Privilege Style, and TUI.

We can now make an overall assessment of what happened: how many people were deported, to where, using what airlines, and how much it all cost. Unless otherwise stated, the findings here come from responses to Freedom of Information Act requests by No Deportations and Hanna Rullmann, and flight-tracking from Calais Migrant Solidarity.

Key points

- The Home Office hyped its deportation rush as targeting refugees arriving in boats from Calais. The immigration minister said they would deport 1,000 Channel-crossers; in fact we estimate 136 were deported.

- Instead, the majority of people on the flights were European nationals. This is the first time the Home Office has used charter flights to deport Europeans en masse – possibly due to lack of commercial flights because of COVID-19 travel restrictions.

- Because they were carried out in a chaotic rush, flights went ahead with hardly anyone on board. In one case, just one person was deported on a plane to France.

- The average cost of flights was over £190,000 (in 2020). The average cost per person was over £12,000 (in the second half of 2020).

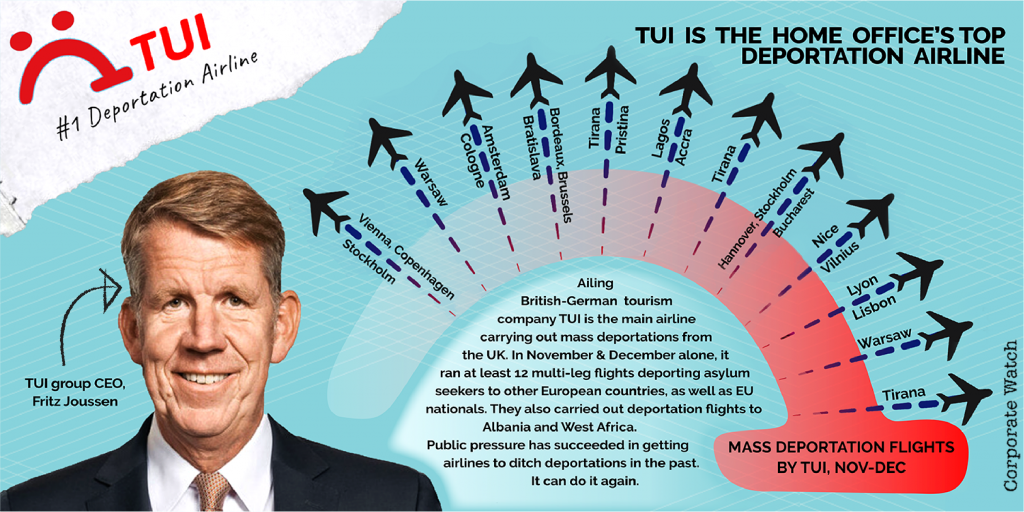

- Six airlines made money from this fiasco. TUI was the Home Office’s main partner. It flew 13 charters to 23 destinations in November and December last year. So far it is still the main deportation partner in 2021.

Background

In August 2020, with migrant boat crossings from France the subject of a media furore, the Home Office began a high-profile deportation campaign targeting Channel-crossers. Mass deportation charter flights from the UK were organised twice a week, mainly to European countries. The Home Office said this would deter arrivals by “send[ing] a message to the people trying to cross the Channel and to the people smugglers that we are getting people out of the country.” In September, immigration minister Chris Philp named a target of deporting 1,000 people who were eligible to claim asylum in other European countries.

At the same time, this was also a chance to show how the government was ‘taking back control of its borders’, fulfilling the Brexit mandate of enforcing hard-line immigration policies. The irony was that, in order to carry out these deportations, the Home Office had to rely on the very European Union agreements it was about to lose access to.

The bulk of these flights were to EU member states that accepted responsibility for assessing Channel-crossers’ asylum claims under the Dublin III Regulation. This is an agreement between EU countries which includes returning refugees to the first “safe country” they were present in. When Brexit hit on 1 January 2021, the UK would drop out of the Dublin agreement and no longer be able to use this mechanism.

Perhaps because of this, the Home Office made a decision to try and rush through as many deportations as possible ahead of the deadline. From early 2020, under a project called “Operation Sillath”, officials flagged Channel-crossers for expedited deportation, in particular to France. Dublin III deportations are usually carried out on the basis of biometric evidence – i.e., someone’s fingerprints have been registered in another country. But in Operation Sillath, France agreed to accept deportees based on much weaker circumstantial evidence. A French Interior Ministry source told Le Monde there was a “secret agreement made with the British… It is only for migrants who arrived in ‘small boats.’ The British tell us they have spent five months in France and we say OK, when very often there is no proof of that and it’s not true.”.i

This wasn’t the only irregularity. Others included immigration officers using an ‘abridged’ interview to screen Channel-crossers, which left out key questions to help identify people who had been victims of trafficking (until the High Court ordered the Home Office to reinstate the questions). This hurried processing meant many of these deportation attempts were of questionable legality and would be successfully challenged in the courts.

Priti Patel with Dan O’Mahoney, ‘Clandestine Channel Threat Commander’. Source: gov.uk

31 charter flights

We identify 12 August as the start date for the Home Office’s deportation campaign against Channel-crossers. There were 16 other deportation charters earlier in 2020 – but these did not target asylum seekers in the same way, and were not spun as a response to the boat crossings. The operation ended on 31 December, when Dublin deportations were no longer possible. The government said it would make “bilateral agreements” with countries to replace Dublin III. But so far it has failed to sign a single one – with a recent report in The Independent claiming that France, Belgium and Germany have “ruled out” the idea.

There were a total of 31 deportation charter flights between these dates (for a full break down, see this spreadsheet). They were mostly multi-stop flights deporting people to two or three different countries at a time. So in total they flew 51 “legs” to 21 different countries. Flights mostly left on Tuesday and Thursday mornings from either Stansted or Birmingham airports. Despite the media hype, only 19 of these flights actually carried Channel-crossers.

In total, there were 47 mass deportation charter flights in 2020. This is significantly higher than the previous year – there were just 20 charter flights in 2019.

Six collaborating airlines

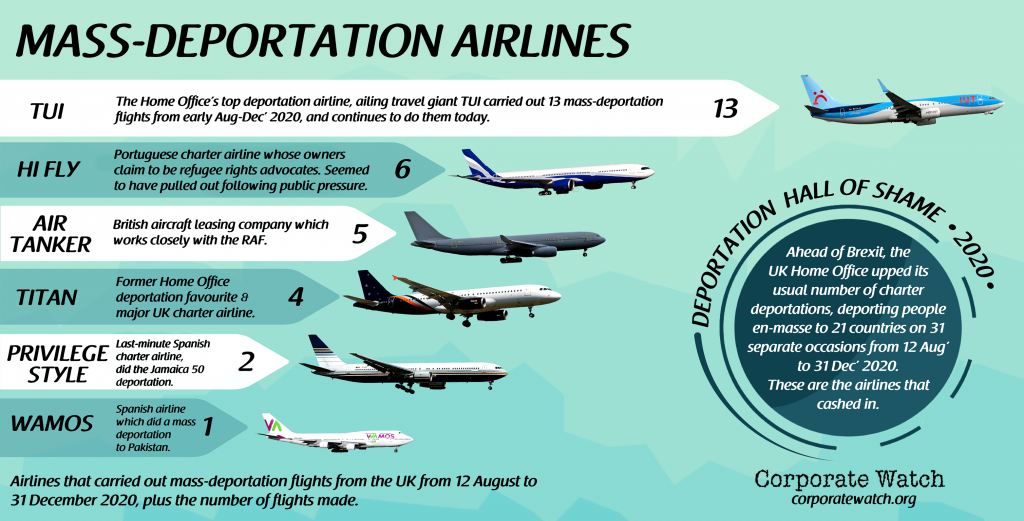

Six airlines collaborated with the Home Office on these charter flights: TUI (13 flights), Hi Fly (6), AirTanker Services (5), Titan (4), Privilege Style(2), and Wamos (1).

The first deportations in August were carried out by Hi Fly, a new deportation partner for the Home Office, alongside long-time collaborator Titan. But Hi Fly’s involvement stopped in early October. This may be connected to campaigning calling on the company to stop deportation flights – Hi Fly’s owners presented themselves as advocates of refugee rights.

AirTanker Services flew the remainder of the deportation charter flights in October. Although these flights were made with AirTanker’s Airbus A330 G-VYGM, Titan flight numbers (ZT/AWC) were used. This may mean the plane was flown by Titan crew using a loaned aircraft.1

In November, TUI took over running the bulk of deportation charters, and has been the go-to provider ever since. TUI has carried out the majority of flights in the latter half of 2020 and continuing into 2021.

There were two notable exceptions: the controversial charter flight to Jamaica on 2 December, and one to Warsaw on 8 December. These were flown by Privilege Style. High-profile campaigning against the Jamaica flight led a number of airlines, including Titan and Hi Fly, to issue public statements saying they were not involved. It is possible that Privilege Style was brought in last minute after other contractors pulled out. The company has not worked for the Home Office since December – but it regularly carries out charter deportations from other European countries, notably to Afghanistan for Germany and Austria.

Wamos, another Spanish airline, carried out one flight, deporting 18 people to Pakistan on 15 December. This was the first time they flew a deportation charter for the Home Office. They may have come to the government’s attention after providing COVID-19 repatriation flights to the UK in Spring 2020.

How much did they cost?

The Home Office doesn’t give too much away about the contracts and costs for its charter flights. It uses the argument of “commercial interests” to refuse to respond to Freedom of Information requests on individual flights. However, it does provide overall costs for each quarter of the year, which give some insight into how much airlines stand to make from the deportation charter business.

2020 Deportation Charter Flight Costs

Period | # of flights | # of deportees | Total cost | Average cost per person |

Q1 | 5 | 51 | £1,406,033.23 | £27,569.28 |

Q2 | 7 | 285 | £1,105,931.02 | £3,880.46 |

Q3 | 12 | 225 | £2,278,236.44 | £10,125.49 |

Q4 | 23 | 322 | £4,307,440.31 | £13,377.14 |

*Data from FOI requests by No Deportations

The approximate average cost to the Home Office of a deportation charter flight was £193,567 in 2020. In fact, full costs may be even higher as the Home Office says these figures “do not include any other costs that may be charged to us retrospectively”.

There is no breakdown of what these costs involve. Paraic O’Brien, reporting for Channel 4, has estimated a figure of approximately £30,000 to charter a plane from the UK to France. Some flights included in the figures were long haul to destinations such as Jamaica, and many were multi-stop to several countries. Even so, the overall costs include more than just charter fees to the airlines.

Other factors may include costs of guards (“escorts”) and for transport from detention centres, both of which are provided by contractor Mitie; and agency fees for the company which books all the Home Office’s flights, Carlson Wagonlit Travel. Another unknown is whether the figures cover the costs of delays and cancellations.

Over the August-December 2020 period, the Home Office spent more than £10,000 per person on its charter deportations. In the last quarter, the average was over £13,000 per person. As The Guardian reported, this was “more than 100 times the average cost of a ticket on a scheduled flight, and a 11.5% increase on the same period in the previous year”.

Border Force Channel-crosser propaganda video

For some flights, the per person costs were much higher than this average. On one occasion, an entire plane was used to deport only one man to Rennes, France. The former director general of Immigration Enforcement was quoted saying this flight was not a good use of public funds, and that “normally the flight would have been abandoned”. The demand to appear “tough” on Channel-crossers may have put the Home Office in a position where they felt they had to pursue this deportation despite the ridiculous costs involved.

Who was on the flights?

The Home Office claims to have deported 412 people between 12 August and 31 December 2020. But despite the Home Office PR campaign focusing on deportations of people who had crossed to the UK in “small boats”, the large majority of these people were not “Channel-crossers” at all. In fact, our estimate is that only 136 “Channel-crossers” were deported – far fewer than the 1,000 figure flagged by the immigration minister.

Based on announcement letters (here’s an example) published by the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association (ILPA), it appears that most of the people deported were EU nationals, as well as nationals of Albania, Nigeria, Ghana, Pakistan and Jamaica. Besides refugees, they included ‘foreign national offenders’ being deported following a prison sentence, as well as possibly other “immigration offenders” – e.g., people who just overstayed their visa.

The latter five countries have been long-term targets for Home Office charter flights over the last decade. The UK has longstanding diplomatic agreements with them that include deportation deals. The EU nationals deported were mainly citizens of Eastern European countries, particularly Romania and Poland. Eastern Europeans have become the Home Office’s main deportation targets in the last five years, overtaking deportations to Asia and the Middle East since 2015. But until last year East European deportations, except for Albania, were carried out using much cheaper scheduled tickets – notably on Easyjet flights. (For more all on this see our earlier overview reports on charter flights and scheduled airline deportations.)

Between August to October 2020, the Home Office did follow its announced plan of focusing on “Dublin III” deportations of Channel-crossing refugees to European countries. That changed from October. The Home Office carried on with its rapid schedule of two charters per week, but now only a minority of the deportees and destinations were “Dublin” related. By December the Home Office’s plan had clearly unravelled: there was just one “Dublin” stop in Lyon, France, on 10 December, seemingly to deport only one person.

In fact Dublin deportations were still being scheduled – but those legs were being cancelled or not flown on the day. This was largely due to the success lawyers were having in challenging the rushed procedures used in these Dublin deportations. As discussed above, “Operation Sillath” involved hurriedly and haphazardly arresting, detaining and serving removal directions – while ignoring the many valid legal reasons for asylum seekers’ claims to be processed in the UK. As a result, many of these deportation orders were quashed by the courts. A court ruling that Spain lacked adequate reception conditions frustrated Dublin returns to that country – after reports emerged of refugees on a Madrid flight being dumped at the airport with no chance to claim asylum there. This caused the grounding of an entire flight on 17 September. Finally, in December, a COVID-19 outbreak in Brook House IRC – the main detention centre where people were held before the flights – also contributed to the cancellation of most of that month’s charters.

Home Office propaganda video.

Faced with the high costs for low deportation numbers, and the cancellation of whole “Dublin” flights, it appears the Home Office started laying on extra legs to Eastern European countries as a way to fill seats. This increased the flights’ “value for money”. The Home Office continued to claim it was fighting the Channel crossings, even though the number of Channel-crossers on board was minimal.

Flying EU nationals on charter flights may also have solved another problem for the Home Office. Before 2020, European citizens had been deported on standard scheduled flights, using Easyjet and other airlines. But now COVID-19 travel restrictions grounded many commercial flights. It seems no coincidence that the charter flights to Poland began at the height of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, while Poland’s borders were closed and commercial flights were out of the question. Similarly, just last week (in April 2021) the Home Office arranged its first ever charter deportation to Vietnam, a country which has largely been closed to international travel since the start of the pandemic.

To sum up: while Home Office’s PR heavily promoted the idea that its charter flights between August and December 2020 were returning Channel-crossing asylum seekers, this was far from the whole story. Although the data does not specify how many people were asylum seekers returned under the Dublin Regulation, we estimate that only 136 Channel-crossers were deported during this period.2 Most of the deportees were actually Albanians (77), a nationality that has topped the deportation tables for several years running, followed by Poles (47) and then Lithuanians (42).

Border Force boat in the Channel. Source: gov.uk

Spin, misery, profit

The Home Office managed to deport far fewer than its announced target of 1,000 “Channel-crossers”, spent millions, and flew planes almost empty. By their own standards, the Channel-crosser deportation drive was a remarkable failure. Nor is there any sign that it acted as a “deterrent” – boat crossings have not ceased.

None of this is unusual or surprising. The Home Office has a long record of missed targets and “deterrent” strategies with no evidence of success whatsoever. (See The UK Border Regime for detailed discussion.)

Once again, these measures seem much more like a hollow PR exercise directed at right-wing media than any kind of serious strategy. What they do achieve is to help further damage the lives of many of those who were deported – pushing people to self-harm, re-traumatising survivors of torture and trafficking, for the sake of creating a spectacle of immigration enforcement. Meanwhile, as the figures we surveyed above suggest, they help generate handsome revenues for the Home Office’s partner airlines.

Notes

1 In 2021 AirTanker Services planes (G-VYGK) have continued to be used for deportation charters for the Home Office to countries including to Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and Romania. They also appear to have flown deportation charters for other EU countries like Germany.

2 Calculated by adding the total deportations to countries not on ILPA’s list from the FOI data.

i This made use of Article 13(2) of the Dublin III regulation, which allows one country to submit a “take-charge” request to another country, if there is evidence the asylum seeker had been there irregularly for more than five months.

See here for a break down of charter flights from August to December 2020.