An unhealthy business: major healthcare companies use tax havens to avoid millions in UK tax

[responsivevoice_button]

While in public they have been presenting themselves as the future of the NHS, a Corporate Watch investigation into the accounts and finances of five of the major private healthcare companies has found widespread use of tax havens,* including the British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, Jersey, Guernsey and the Cayman Islands, and tax avoidance schemes Barclays or Vodafone accountants would be proud of.

While in public they have been presenting themselves as the future of the NHS, a Corporate Watch investigation into the accounts and finances of five of the major private healthcare companies has found widespread use of tax havens,* including the British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, Jersey, Guernsey and the Cayman Islands, and tax avoidance schemes Barclays or Vodafone accountants would be proud of.

Click here to read the Observer article ‘revealing’ the investigation, with responses from the companies.

- Spire Healthcare, the UK’s second largest private healthcare company, is channelling £65m a year through a Luxembourg subsidiary of Cinven, its private equity owner, almost wiping out its taxable UK earnings.

- Care UK, which operates NHS treatment centres, walk-in centres and mental health services across England, is reducing its tax liability by routing £8m a year in interest payments on loan notes issued in the Channel Islands.

- Circle Health, the self-styled “social enterprise” that became the first private company to take over the management of an NHS hospital, is owned by companies and investment funds registered in the British Virgin Islands, Jersey and the Cayman Islands.

- Ramsay Health Care, the company with the greatest number of healthcare provision contracts in the NHS, has used a subsidiary in the Cayman Islands to finance the purchase of a French health company for its Australian parent company.

- General Healthcare Group, the biggest private hospital group in the UK, has registered the ownership of its hospitals through subsidiaries in the British Virgin Islands, potentially avoiding stamp duty when its owners come to sell.

Spire, Care UK, General Healthcare Group and Ramsay** are all carrying significant levels of debt after their owners financed their acquisitions through borrowing. The interest being paid to banks and bondholders – which is far higher than the government would be paying for equivalent sums – is also serving to reduce taxable profits.

All of the companies investigated have been lobbying in support of the government’s health reforms, which they hope will increase their share of NHS work and the amount of patients paying for private healthcare.[2]

If accused of tax avoidance the companies will reply that everything they do is legal. As the accounts of their offshore subsidiaries are not publicly available – and the companies have not responded to Corporate Watch’s requests to see them – it is impossible to dispute that. But being legal is not the same thing as being right, and the government’s promises that companies can be regulated into doing a good job for the NHS are further undermined with evidence of how easily they are getting round the tax obligations that should help pay for it.

Spire Healthcare: profits, what profits?

Spire Healthcare is one of the biggest private healthcare providers in the UK. It treats 25% of its patients through the NHS, providing operations such as hip replacements and varicose vein surgery, and is one of the biggest private providers of healthcare services to the Department of Health.[3] Spire was formed in 2007 after private equity firm Cinven bought 25 hospitals from Bupa for £1.4bn. Since then it has acquired 12 more hospitals to take its current total to 37. Spire’s 2010 annual report described the coalition’s health reforms as “very positive for the private sector” and the company has said it is aiming to be a “provider of choice” to GP commissioning groups.[4]

Its accounts show that, at root, Spire is a profitable business: its revenue rose by 4% to £643m in 2010 and it posted an operating profit of £123m.[5] Much of that was eaten away by the £108m in interest it had to pay on the £1.3bn worth of bank loans taken out by Cinven to finance its acquisition of Spire. But even after that has been paid, there should still be £15m of taxable profit remaining.

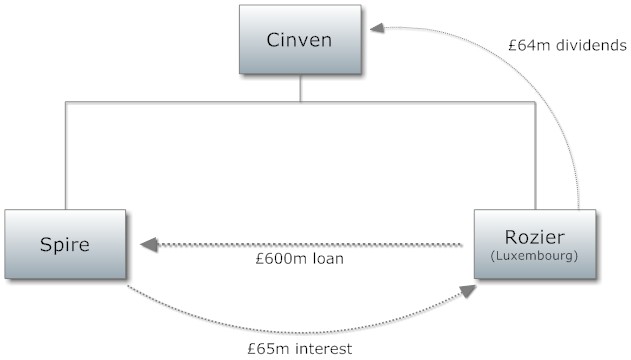

However, in addition to the interest on the bank loans, Spire has also paid £65m in interest on almost £600m of loans it owes to a company called Rozier, which turns out to be a Luxembourg-registered subsidiary of Cinven, Spire’s private equity owner.[6]

Rozier’s accounts show it paid almost £65m to its owner in 2010 as yields from its own shares, which carry a similar rate of interest to the loan it has given Spire.[7] In Luxembourg, these shares are treated as debt, so Rozier deducts the interest on them from its Luxembourg tax bill (in the process almost wiping it out). But the UK tax authorities will treat it as dividends. UK companies don’t get taxed on income from their subsidiaries (to avoid them being taxed twice) and as dividends count as income, not profit, the money Cinven receives from Rozier is therefore tax deductible.

All of which means Spire Healthcare made an operating profit of £123m in 2010 but was able to declare a £53m loss for the same period. In fact, its accounts show its finance costs have pushed it into loss every year since it was formed in 2007.

It has only paid any tax at all – just over £3m over three years – because HMRC has deemed some expenses “not deductible for tax purposes”. And at the same time, its private equity owner can make the best part of £65m a year!

Care UK: borrowing with interest

Care UK is one of the biggest private providers of NHS treatments. It is the largest operator of independent sector treatment centres and also operates GP practices, NHS walk-in centres, GP out-of-hours services and Clinical Assessment and Treatment Services around the country. The company has had contracts with all of the current Strategic Health Authorities, works with one in three Primary Care Trusts and is currently bidding to take over the management of the NHS George Eliot Hospital in Nuneaton.[8] It also runs 85 residential homes and provides care for over 17,000 people across the UK.

Previously publicly listed on the London stock exchange, it was bought and taken private by the private equity company Bridgepoint Capital in 2010. The new owners immediately restructured the company, increased its levels of debt and introduced a tax avoidance scheme that sees interest payments on borrowings and dividends on shares channelling money out of the company (and see here for a previous Corporate Watch article about the Southern Cross-style split Care UK is making between ownership and management of its care homes).

Care UK did not make an operating profit in 2010 due to the various costs of restructuring the company under its new owners. However when it does, the restructuring has ensured that, while its owners will enjoy healthy returns, the public finances may not. Its accounts show Care UK paid £41m in finance costs in 2010.[9] £25m of this was the 10% interest on the £250m bond it had to issue for Bridgepoint to buy it in the first place.

Of the other £16m, £8m is going in interest payments on £130m of loan notes – essentially IOUs – Care UK issued on the Channel Islands stock exchange straight after its acquisition by Bridgepoint.[10] Usually, when a UK company borrows from a non-UK company it has to ‘withhold’ 20% of the interest on the loan – ie it has to pay 20% of the value of the interest to the UK tax authorities. But there are exceptions to this, one being if the loan notes are issued on a stock exchange designated by the UK Inland Revenue as eligible for what’s called the “quoted Eurobond exemption”. The Channel Islands is one such exchange.

Care UK’s accounts do not disclose who has bought these notes but, given their terms and the history of private equity deals, a subsidiary of Bridgepoint, routed in a similar way to the Spire-Rozier-Cinven structure above, is likely. The terms of the notes make it clear that if Care UK cannot afford to pay the interest one year it can be rolled over to the next year, to all be paid off by 2018 (when all remaining interest from previous years will be paid). But this decision may not be made by Care UK, as the terms of the £250m bond it issued are clear that the bondholders can stop Care UK paying interest on other loans or dividends if they are not happy with its financial performance. The terms of the bond also state that at the end of the year the bondholders get their interest payments before anyone else. So if the company isn’t doing too well and can’t afford all the interest it has to pay, the holders of the loan notes would lose out.

But in terms of the money Care UK is paying in British tax, it doesn’t really matter who is buying the shares as the interest payments, whoever they are going to, are taken off Care UK’s taxable earnings.

In addition, £8m a year is going straight to the Bridgepoint fund investors that bought Care UK, as dividends on £126m of “cumulative preference shares” in the company. When the Bridgepoint fund bought Care UK, it invested £130m into the company. However, it put £126m of this into these preference shares, with only £4m going into ordinary shares.

Ordinary shares are what we usually think of as shares: if you have one, you own a part of the company, have voting rights and receive dividends when the company performs well enough. Preference shares do not allow voting rights but guarantee a dividend every year, in this case of 16%. This means the company does not have to be profitable for its owners to be making a regular return from it. Care UK’s accounts show HMRC appears to have decided taking these dividends off the company’s taxable earnings would be a step too far and deemed them “not deductible for tax purposes”. However, as major investors in the Bridgepoint fund are American (ironically, many are public sector pension funds), and as companies pay a reduced rate of tax on preference share income in the US, they will still enjoy a certain amount of ‘tax efficiency’.[11]

Clarification: Care UK has since said HMRC only allowed some of this interest to be tax deductible)

Circle Health: offshore enterprises

Circle Health took over the management of Hinchingbrooke hospital last month, becoming the first private company to win a contract to manage an NHS hospital. It has also operated NHS services in Burton, Nottingham and Bradford, private clinics in Stratford and Windsor and a private hospital in Bath. It is currently building a second private hospital in Reading and is bidding to take over the management of the George Eliot Hospital in Nuneaton, another NHS hospital.[12] A self-described “social enterprise” headed by former Goldman Sachs investment banker Ali Parsa, Circle has been among the foremost advocates of the benefits the “power of competition” can bring to the NHS.

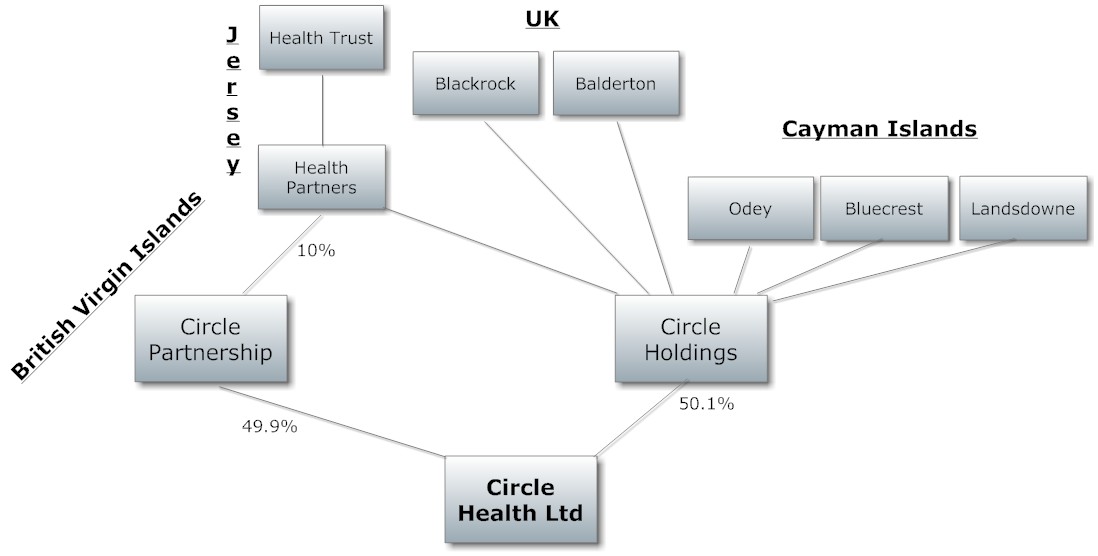

Circle was founded in 2004 and the costs of its rapid expansion have meant it is yet to make any significant returns for its owners. But its accounts show that, when it does, those owners are well-placed to minimise their tax burden. As the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has previously shown,[13] Circle’s corporate structure is far from the social enterprise model its publicity claims. Circle Health Ltd – the company that actually provides healthcare – is 50.1% owned by a company called Circle Holdings, with the other 49.9% owned by Circle Partnership.[14] Circle Partnership is part-owned by Circle employees and is the social enterprise part. But while this may mean some of its staff benefit when the company starts making a profit, as it is registered in the British Virgin Islands, these benefits will not be shared. Companies registered in the Caribbean island do not have to pay tax on dividends from investment in a UK company.

Companies registered in the British Virgin Islands do not have to make their accounts public – and Circle did not respond to Corporate Watch’s requests to see them – so we cannot see exactly how much of the Circle Partnership is owned by its employees. But Circle Holding’s financial statement shows that at least 10% of shares in Partnership are held by a company called Health Partners Limited, a “wholly owned subsidiary of Health Trust (Jersey), a family trust of which the Chief Executive Officer [Ali Parsa] is a beneficiary”, and which, as suggested, is registered in Jersey – another tax haven![15]

Health Trust also owns a share of Circle Holdings (again through Health Partners), which used to be incorporated and domiciled for tax purposes in Jersey. The £7m interest Circle Health was paying on a £67m loan it had taken from Holdings would therefore go back to Jersey. When it listed on the Alternative Investment Market in May 2011, raising £45m in the process, it also changed its residence for tax purposes to the UK.[16] But as the major shareholders in Circle Holdings include the Jersey-registered Health Trust and five investment funds, three of which – Lansdowne UK Equity Fund, BlueCrest Venture Finance Master Fund Ltd and Odey European Inc – are registered in the virtually tax-free Cayman Islands, this move may not be as public-spirited as it may first appear.[17][18][19][20]

In addition to this, money will leave the company through the ownership of its hospitals. Circle’s Bath hospital is owned by Health Properties Bath, another Jersey-registered company, which Circle pays £3.2m a year in rent.[21] Health Properties turns out to be owned by Circle Holdings (39%) and Health Estates Fund Ltd (58%), a “related party property fund advised by the [Circle] Group”, which is also registered in Jersey.[22] And, as a final reminder of Circle’s links to speculative finance, the remaining 3% is owned by Lehman Brothers, which originally loaned money to build the hospital.

General Healthcare Group: preparing for gains?

The other private healthcare companies we looked at do not appear to be seeking ‘tax efficiency’ quite as aggressively as Care UK, Spire and Circle, though, in General Healthcare Group’s case, the terms of service for the huge amount of debt it has means it does not have a choice. GHG describes itself as “the leading provider of independent health care services in the UK”.[23] It owns BMI Healthcare, the biggest private healthcare provider in the UK. BMI has a network of over 70 hospitals and clinics, which treat NHS patients through the Choose and Book system, and is looking to sign more contracts with NHS trusts in a range of areas in the near future. In December last year it signed a contract to provide procurement and consumables purchasing on behalf of four London NHS trusts.[24] It has strongly argued more patients should use private providers within the NHS. Adrian Fawcett, CEO until May 2011, looked forward to the opportunity a two tier NHS would offer his company, saying he wants “co-paying [to be] seen as standard, so patients pay on top of their NHS care, for medicines or for their own room with extra facilities.”[25]

GHG is owned by a consortium of companies including private equity firms Apax Partners, London & Regional and Brockton, and Netcare, South Africa’s leading hospital group, which holds a controlling, 50.1% share. They bought GHG for £2.2bn in 2006, from BC Partners, its previous private equity owners. Netcare’s previously existing UK operations, which saw it become one of the first companies to run NHS Independent Sector Treatment Centres, have been brought into the GHG group of companies.

The GHG deal was financed by borrowing and issuing bonds for a total of £1.9bn from a variety of third party sources. As this was all set up pre-credit crunch, the interest rates are low, although GHG had to agree to certain conditions. The prospectus for almost £400m of asset-backed bonds issued by the company in May 2007 for example, makes clear that companies within the group must be resident for tax purposes in the UK, so the bondholders do not incur any unwelcome tax risk.[26] (However, even its relatively low interest rates may not save it from a debt burden that is due to mature in 2013. The Financial Times has been reporting that distressed debt investors, including private equity healthcare investor Kohlberg Kravis Roberts are “circling” the company and buying parts of its debt.[27])

For Netcare and its private equity partners, the desire for cheap financing would have taken precedence over ‘tax efficiency’ – unsurprising given the amount of debt it was taking on – and in any case the tax collector Netcare will be most concerned about will be sat in an office in South Africa, not the UK.

But even here the potential for significant tax avoidance remains. Each of the hospitals owned by GHG are actually owned by separate subsidiaries all incorporated in the British Virgin Islands (there are 47 in total). These are registered in the UK for tax purposes, as insisted upon by the terms of the bonds, but they are still British Virgin Islands companies. This means that when Netcare and partners come to sell GHG, they can transfer the ownership of the hospital-owning subsidiaries to the new owners in the British Virgin Islands, thus avoiding UK stamp duty. Considering its accounts value its total property, plant and equipment at £1.7bn,[28] this would represent a huge saving for the company and would allow Netcare to charge a higher price (which buyers will be prepared to meet as they know they will not have to pay the stamp duty).

Ramsay Health Care: an offshore mystery

Ramsay Health Care, Australia’s biggest private hospital chain, bought Capio UK in 2007, acquiring its 22 hospitals and nine Independent Sector Treatment Centres for NHS patients. Ramsay now has 22 hospitals across the UK and almost 60% of its work is from the NHS, a proportion that has increased for the past five years. A 9% revenue increase in 2010 came in large part from the increase in NHS work the company was getting through the Choose and Book system. Ramsay also bid for the contract to run Hinchingbrooke hospital but lost out to Circle.

Ramsay’s accountants will, like their counterparts at GHG, be more interested in their parent company’s tax authorities that HMRC. Nevertheless, its accounts show it is not averse to dealing with another Ramsay group company registered in the Cayman Islands. In 2010, Ramsay UK borrowed £57m from RHC Finance Ltd, a subsidiary of its Australian parent registered in the Caymans, to finance the acquisition of a 57% share of the Proclif Group, re-branded as Ramsay Sante, a leading French private healthcare company.[29] This led to £1m leaving the UK for the Cayman Islands in interest payments. Why the company routed the financing for its investment through the Caymans is unclear as RHC Finance’s accounts are not made public. When asked, Ramsay UK told Corporate Watch that RHC is a subsidiary of its Australian parent and the UK company does not have any information about its operations. When Corporate Watch pointed out it had borrowed £57m from it, a spokesperson said the company would get back to us with more details. There has been no contact since.

Welcome to the new, transparent NHS.

* There is no single accepted definition of what a tax haven is, but according to the Tax Justice Network (TJN), the central feature is that “its laws and other measures can be used to evade or avoid the tax laws or regulations of other jurisdictions.” Also relevant for this article is their secrecy, which the TJN calls “the main element of their attractiveness”. Some people use the term ‘secrecy jurisdiction’ interchangeably. The full TJN briefing can be found here: www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/Identifying_Tax_Havens_Jul_07.pdf ** The majority of Ramsay’s debt is held by its Australian parent.

** All the companies discussed have several different UK subsidiaries but, for ease of explanation, we will not distinguish between UK subsidiaries unless necessary. Much of the money appears to be routed through the Channel Islands stock exchange and other subsidiaries registered in Guernsey,[30] avoiding withholding tax by using the “quoted Eurobond exemption” (see the Care UK section), but as their accounts are not publicly accessible, and as Spire would not show them to Corporate Watch, it is difficult to know in exactly how this is happening.

*** Private equity firms invest other people’s money and take a share of the profits made from their investments, setting up special funds to do so, in this case the £4bn Bridgepoint Europe IV fund. Investors include the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the New York State Common Retirement Fund and the Ohio School Employees’ Retirement System.[31]

See also:

Care UK and private equity: another Southern Cross? December 22, 2011

Under the microscope: pathology gets the Serco treatment November 9, 2011

Co-operating and competing to privatise the NHS August 12, 2010

The vultures circle: private equity and the NHS May 10, 2011

Wolves cry wolf: selling competition in the NHS April 6, 2011

Signs of things to come: The privatisation of the NHS February 10, 2011