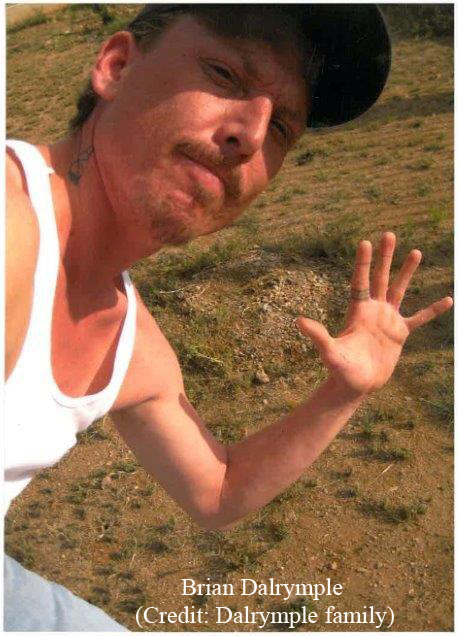

Brian Dalrymple Inquest: Day 1

[responsivevoice_button]

Who takes responsibility when a detainee dies in custody: the State or a corporation?

On 14 June 2011, a white American tourist landed at Heathrow. It was to be a holiday from hell. Six weeks later this man died in a British detention centre.

An inquest opened yesterday at West London Coroner’s Court three years after the death of 35 year-old Brian Dalrymple.

He was held at Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre (IRC) for 43 days, before being transferred to Serco’s Colnbrook IRC where he spent the last week of his life.

The coroner started the proceedings by telling the jury that this was not a question of attributing blame, but it was to establish how and in what circumstances he came by his death while detained by the state.

The lawyers, however, seem to have other ideas. There are a lot of them at this inquest, representing each of the seven interested parties, none of which want to be blamed for Dalrymple’s untimely death: the Home Office, the NHS, and the other five companies that run the detention centres and private health clinics Mr Dalrymple encountered (or not) during his incarceration. These businesses include Serco, GEO Group, Nestor Primecare Services and The Practice PLC.

(The Dalrymple family is also represented, and Brian’s mother is listening via video link from America.)

Such is the extent of Home Office privatisation and outsourcing of immigration detention that it looks set to wash its hands of any responsibility for Mr Dalrymple’s death in its custody.

And that is a terrifying prospect. Has the Home Office set up a system of immigration detention where companies have more control than the state?

The court heard more details about Mr Dalrymple’s time in the UK. He told the British immigration officers at the Heathrow arrivals desk that he planned to visit Stonehenge, Scotland, Poland and Germany. He had a return ticket booked for 27 June, a fortnight later.

However, the officers could not find any other documentation to support this itinerary and they were suspicious about his luggage.

Mr Dalrymple was traveling light. All he had was a small cardboard box, containing a coat, a cut throat razor and $2000 in cash. He assured them he would keep the razor blade in the boot of a car while he traveled around Britain.

The immigration officers that questioned him at Heathrow found him “uncooperative”. They noticed his unusual behaviour. They did not know that he suffered from an anxiety disorder and schizophrenia.

Mr Dalrymple was kept overnight at Heathrow and booked on a return fight for the following day. He refused to board that flight.

UK Border Agency officers then moved Mr Dalyrymple to the nearby Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre (IRC), which is run by the GEO Group, an American private prison company.

The court then heard evidence from Marie Jugdev, the Home Office’s deputy immigration manager at Harmondsworth in June-July 2011. Although her job title may suggest a position of responsibility, in her two hours on the witness stand it appeared she had very little knowledge of what happened inside Harmondsworth. Just “expectations” about what the contractors, GEO, should have done for the Home Office.

For instance, GEO should have told her that its guards had seen Mr Dalrymple over a period of weeks standing in the corner muttering to himself, urinating on the floor of his cell, throwing food and mentioning persecutory behaviour by the Black guards. But Ms Jugdev says GEO did not tell her about this. She was aware that GEO kept detailed notes on detainees’ behaviour, but this information was not shared with her, nor did she ask for it. (Ms Jugdev was physically located at the Harmondsworth site, but it was not the Home Office’s responsibility to observe the daily “operational” goings on there)

GEO did, however, ask her permission for Mr Dalrymple to be “removed from association”, for being racially abusive to staff and detainees as well as damaging “company property”.

Moving a detainee to a more restrictive regime is something that requires Home Office approval. And it was Ms Jugdev who signed the Rule 40 form that authorised an initial 24 hours of segregation, on 2.35pm on 24 July, a week before Mr Dalrymple’s death.

Ms Jugdev has no medical qualifications or mental health awareness training. She did not meet Mr Dalyrymple before authorising his removal from association. In fact, she cannot recall ever meeting him.

However, a Chief Immigration Officer had met Mr Dalrymple weeks previously and was concerned by his behaviour, which included claiming asylum. Ms Jugdev said she did not think it was a sign of mental illness that a white American citizen had sought asylum in Britain, because she said lots of people claim asylum to delay their removal from the UK.

But the Chief Immigration Officer thought otherwise. He twice asked for a psychiatric and medical assessment of Mr Dalrymple. Although this request went to Ms Jugdev’s team, she did not know if any of them had passed it on to the healthcare department at Harmondsworth, which is run by a separate company.

The assessment did not happen at Harmondsworth. Ms Jugdev said she “can remember a period of difficulties in getting healthcare staff”.

The Chief Immigration Officer was told Mr Dalyrymple was ‘fit to fly’, because it was Home Office practice at that time that anyone was presumed fit enough to be deported unless the Healthcare staff told them otherwise. This practice has since changed, and the Home Office has a system of more pro-active checks in place. Ms Jugdev, who still works for the Home Office at Harmondsworth, said she has “more confidence now” that the healthcare arrangements at the centre are adequate.

An hour and a half after authorising Mr Dalrymple’s separation, Ms Jugdev emailed the UKBA manager at the another facility, Colnbrook IRC, asking if they could “swap” Mr Dalrymple with one of their detainees. Ms Jugdev felt a “change of scene could benefit Mr Dalrymple”. Ms Jugdev’s email was prompted by a GEO manager who said that because Mr Dalrymple had been using the “N-word” it was risky putting him back on the wing with people he had insulted.

The email did not raise any healthcare concerns about Mr Dalrymple. Ms Jugdev said a GEO manager had mentioned that Mr Dalrymple had refused medical treatment, but she did not ask GEO what the treatment was for. Mr Dalyrymple had been taken to Hillingdon Hospital on 16 July with hypertension and high blood pressure. He had discharged himself, against medical advice. (Mr Dalrymple would die from a ruptured aorta.)

On 27 July, Mr Dalrymple was transferred to Colnbrook IRC. The court heard that Colnbrook is in fact next door to Harmondsworth (See the photo above, which shows Colnbrook on the right and Harmondsworth on the left, separated by a two lane road). Ms Jugdev estimated that you could walk from one centre to the other “in under a minute”, but detainees must be transferred in a vehicle. Colnbrook is run by another company, Serco. The Jury looked a bit confused by the Home Office’s arrangement.

It is at Colnbrook that Mr Dalrymple died on 31 July, so this transfer process is quite contentious. Was Serco given enough information about Mr Dalrymple’s medical condition and strange behaviour? The lawyers for Serco and GEO became very interested in how Mr Dalrymple made this short journey from Harmondsworth to Colnbrook. Did GEO staff drop him off, or did Serco guards come to collect him?

Ms Jugdev said Serco staff came to collect Mr Dalrymple from Harmondsworth but his medical records were not transferred. Normally they are put in a sealed enveloped and taken with the detainee. This did not appear to have happened, and it is clear some time will have to be spent at the inquest finding out why between Serco, GEO and the Home Office no one managed to move a sealed envelope from Harmondsworth to Colnbrook. This is an inquest into the death of Mr Dalrymple, but it also raises serious questions about the convoluted web of outsourced immigration detention weaved by successive governments.

The inquest continues.