Brian Dalrymple inquest day 4: Serco on the stand

[responsivevoice_button]

Serco guard that collected Dalrymple from Harmondsworth was not meant to escort detainees – “only time in five years”

Crucial medical records were not transferred with Dalrymple between detention centres despite protocol

Serco nurse tells inquest about years of problems communicating with healthcare company at neighbouring detention centre, and says Home Office only made ‘slight improvement’ in early 2014

At West London Coroner’s Court yesterday, the inquest into the death of Brian Dalrymple, an American tourist suffering from schizophrenia, heard about the last days of his life, spent in a segregation cell of a commercially-run British detention centre.

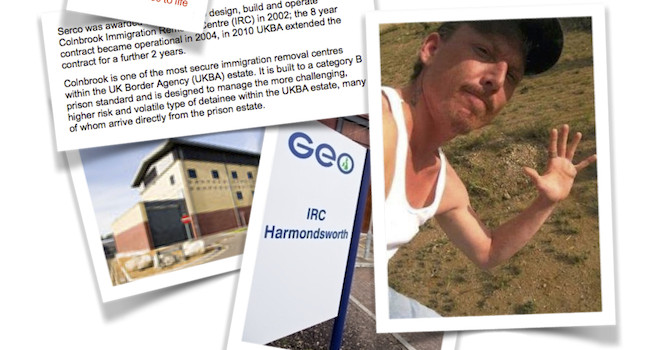

35-year-old Dalrymple died on 31 July 2011 after suffering a cardiac arrest at Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre, near Heathrow Airport. Colnbrook is the UK Home Office’s highest security facility and is operated by the outsourcing giant Serco.

Brian Dalrymple came to Britain for a holiday. Upon arrival at Heathrow on 14 June 2011, immigration officials became suspicious by his behaviour and denied him entry. He was first detained at the Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre, run by the American private prison firm GEO, before being transferred to the neighbouring Colnbrook facility on the evening of 27 July 2011.

The inquest heard from Robert Lewis, a Serco detention custody officer, one of the four person team that collected Dalrymple from Harmondsworth. Brian Dalrymple’s medical records were not transferred with him, in contravention of normal procedures. These notes contained the vital information that Dalrymple had been taken to Hillingdon Hospital on 16 July 2011 with dangerously high blood pressure and discharged himself against medical advice, as well as observations about a deterioration in his behaviour during his time in Harmondsworth.

Robert Lewis said Serco staff were not normally responsible for transferring detainees between detention centres; this was the duty of a separate company hired by the UK Home Office. Lewis said he had worked for Serco at Colnbrook since January 2008, and this was the first time and last time he had worked on this kind of transfer.

Dalrymple appeared agitated and paranoid, Lewis said, and was suspicious about the Serco van being used for the transfer. “He may have felt he was being tricked, not told the truth”, Lewis recalled, since similar vans were used to drive detainees to nearby Heathrow Airport.

The officers tried to reassure Dalrymple that he was just being moved across the road to Colnbrook. A colleague told Dalrymple that he had been to America and asked where Dalrymple was from in the US. Dalrymple replied that he was not from America.

Brian Dalrymple was dropped off at the Colnbrook reception area around 10pm. He was given a routine healthcare assessment by a Serco mental health nurse, Jake Keesony. (Not all the nurses at Colnbrook specialise in mental health; by chance Keesony attended to Dalrymple.)

Keesony told the inquest that he found Dalrymple “peculiar in demeanour”, his behaviour “very odd”. Dalrymple denied having had any history of contact with mental health services. He indicated that his blood pressure was high, but refused to let Nurse Keesony take his pulse.

Keesony said he felt Dalrymple became uncooperative when he saw the nurse’s name badge containing the words ‘mental health’. Dalrymple asserted: “I’m not mental”. He was placed in a segregation cell until such a time as his mental health would be properly checked out.

After the screening, Keesony asked the reception desk for Dalrymple’s healthcare notes. He was told that they had not arrived. So he called Harmondsworth. On the second attempt, at 11.30pm, he managed to speak to an agency nurse, who agreed to fax over the documents. Keesony says he did not receive the fax before he went off shift at 7am. He left a note for the next shift to chase this up and asked the incoming mental health nurse Mark Adjorolo to make a fuller assessment.

Nurse Adjorolo, another Serco employee, said Dalrymple was agitated by the sight of his name badge. He described Dalrymple as dressed shabbily, unshaven and suspicious about his surroundings. “So obviously I concluded that there might be some underlying mental health problem but I couldn’t point my finger at what it was exactly”, Adjorolo told the inquest.

The nurse said that he examined Brian Dalrymple without first trying to obtain his full medical records, because Colnbrook staff “historically had difficulties getting through to Harmondsworth”. (The Harmondsworth healthcare unit was not run by GEO but by yet another company. At that time it was Nestor Primecare Services Ltd).

Communication difficulties persisted from 2011 until early 2014, when the issue was “slightly resolved”. Adjorolo said the Home Office representative on site at Harmondsworth now makes an effort to ensure such calls are answered, although the coverage is “still not 100 per cent”. Serco has also adapted its procedures to ensure a swifter response to detainees arriving at Colnbrook without medical records.

Nurse Adjorolo booked Dalrymple for a psychiatrist to see him, but the earliest appointment was not until 4 August, almost a week later. Serco has since introduced a system of on-call psychiatrists. Adjorolo said: “if that existed then I would have phoned him.”

Adjorolo was one of the medical staff to attend Dalrymple’s cell, number 19, on the morning of 31 July. He found Dalrymple at 9.28am to be not responding and blue in colour, indicating that he was lacking oxygen. Adjorolo assisted with CPR. A defibrillator was attached to Brian Dalrymple’s chest but recorded no electrical connection. Paramedics delivered five shots of adrenaline and an intravenous drip was set up. CPR was stopped at 10.15 am and Brian Dalrymple was pronounced dead.

The Dalrymple family’s lawyer thanked Nurse Adjorolo for his efforts. The inquest continues.

Published with Open Democracy