Capita gets bigger slice of UK immigration cake, chokes on first bites

[responsivevoice_button]

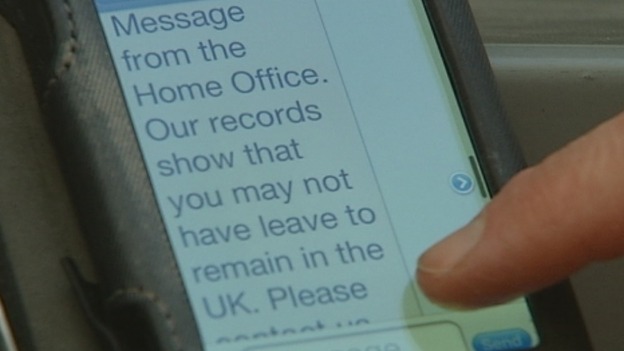

Thousands of migrants received threatening text messages over the Christmas holiday telling them they did not have the right to be in the UK and should leave the country immediately. But many of them reportedly had valid visas, leaves to remain or even British passports. The texts were sent on behalf of the immigration authorities by the outsourcing giant Capita under a new £30 million contract to trace and contact ‘overstayers’. Was this the first of to-be-expected cock-ups in this new ‘bounty hunters’ venture, or is it the shape of things to come as Capita and other private companies take over the immigration and asylum ‘market’? Corporate Watch takes a look.

Crap bounty hunters

In October last year, Capita signed a multi-million contract with the UK Border Agency to trace and contact 174,000 migrant workers and overseas students who had been refused permission to stay in the UK but whose whereabouts were unknown to the authorities. The gap, dubbed the ‘migration refusal pool’, was uncovered in July last year during an investigation by the independent inspector of immigration, John Vine, who at the time estimated the number to be 150,000. By the end of June 2012, the figure had risen to 174,057, despite admissions by the UKBA that many might have left the country voluntarily. The increase was largely due to efforts to “curtail student leave” during the first two quarters of 2012, in what is known as Operation Mayapple, when the leave of 14,100 foreign students was terminated following a notification from a sponsor.

The text messages sent by Capita to people believed to fit this category read: “Message from the UK Border Agency: You are required to leave the UK as you no longer have the right to remain.” The text then urged recipients to contact the UKBA immediately and provided a phone number to call.

However, according to the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association (ILPA), those who received the text included a woman with a valid British passport and a man with a valid visa who had invested £1m in a UK-based business (see here). Many websites and chat forums reported similar cases, with many borrowing Private Eye‘s infamous name for the company: ‘Crapita’.

According to the BBC, one immigration solicitors firm received letters for 31 of its clients (IT specialists from India) demanding that they leave the country, even though they had all left Britain in 2008, when their short-term contracts ended. The UKBA had been notified of this in October 2008 and again in June 2009 (see here).

Moreover, immigration lawyers say the texts were sent out over the Christmas period so as to “maximise effect”, as many would not have been able to contact their solicitors. ILPA said it had asked for the messages not to be sent over the holiday period because it was concerned that “it would be difficult for [recipients] to get in touch with their lawyer and they would be anxious and distressed with no possibility of reassurance.” The request was, of course, declined.

One wonders: Doesn’t this amount to ‘causing harassment, alarm or distress’, as defined by the Public Order Act?

Inaccurate

Capita claimed it was working on the basis of information received from the UKBA but admitted the records might not have been accurate. Yet this inaccuracy was used as a justification to ‘hunt’ for ‘overstayers’ and intimidate others. “This is the first time a government has taken proactive steps to deal with this pool of cases, some of which date back to December 2008,” a statement by the UKBA said.

However, the assumption that those who cannot be tracked down by the system must be overstaying illegally appears to be more politically motivated than based on factual evidence. It is, indeed, part of the government’s “commitment” to appear tough on immigration and increase enforced removals from the current target of 40,000 people a year.

The fourth data protection principle requires that personal data “shall be [kept] accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date.” There is no reason, for example, why the Advance Passenger Information (API) lists, which are provided to the immigration authorities by airlines, should not be systematically checked against immigration records. Such checks have in the past revealed that many people thought of, and talked about, as ‘overstayers’ and ‘illegals’ had in fact left the country of their own accord or had ongoing legal processes, such as appeals against refusal decisions or claims in another immigration category (see here, for example).

Thus, the UKBA and Capita are not only potentially in breach of the Data Protection Act, they are also wasting millions of pounds of public money on the basis of inaccurate information.

Indeed, when immigration lawyers complained that texts were being sent directly to individuals even when these had a legal representative on record, Capita used inaccurate information as a justification: “Capita has been instructed to contact individuals regardless of their legal representation as many of the details the UK Border Agency has on file may be inaccurate and out of date given the age of the cases.”

The contract with Capita follows a pilot project in the London and South East area run by rival company Serco, in which only 20 per cent of those contacted as overstayers had either already left the country or left within six months of being contacted. The aim of the scheme was to ascertain the cost and effectiveness of this approach to tackling the ‘migration refusal pool’. Serco worked, unpaid, on a sample of 7,600 cases as a proof of concept ahead of the competitive tender. Sadly for Serco, the contract went in September 2012 to Capita, which beat Serco and another rival in the bidding process.

Clearing the ‘mess’ with another

According to the terms of the contract, Capita will assist the UKBA in managing the “overstayers backlog” by establishing their whereabouts and contacting them by phone, email, letter or any “other means as appropriate.” The aim is apparently to warn them that they have to leave the country and give them “practical advice” on their departure, as well as assisting them in obtaining travel documents, booking flights and so on. The company claims it will not be involved in the removal of those who “refuse to comply” but will pass on their details to the UKBA – ignoring the fact that, earlier last year, Capita also bought up Reliance, the security firm that is contracted by the UKBA to carry out enforced removals.

In addition, Capita says on its website it will “assist the progression of the cases to enforcement,” without specifying what its role will exactly be. When asked about this, Capita told Corporate Watch this includes “working with the UKBA and assisting with any barriers to return, such as lost paperwork.”

The contract is worth an estimated £30 million over four years (wrongly reported by many media outlets as £40m). It comprises an incentive-based payment structure with payment-by-result elements based on a number of agreed outcomes, which have not been made public. The actual value of the contract is £2.5 – £3 million for initial contact management, £150,000 to develop the casework processes, and £2.5 million for handling 50,000 cases (subject to the UKBA agreeing the casework processes). Further related work could be channelled through the contract so its value could rise to £30 million over four years, depending on the company’s performance (this is known as graduated payment structure and is typically used for mortgages).

Announcing the contract during a session of the Commons home affairs select committee, the UKBA’s chief executive Rob Whiteman told MPs: “Capita will be paid for the number of people who they make contact with and leave. If nobody leaves because they make contact with them, nobody will get paid.” Further details, such as the targets Capita has to meet in order to receive payments, have not been revealed. This led the chair of the select committee, Keith Vaz MP, to comment that the company would be “laughing all the way to the bank.”

More seriously, payment-by-result contracts, such as those used in welfare provision programmes, have shown to be disastrous for public services. One obvious reason for this is that, with such contracts, it is easier and more cost-effective for the contractor to deal with, and get paid for, straightforward cases, while the more difficult or ‘tricky’ ones get ‘parked’, or not dealt with (this is known as ‘cherry-picking’ or ‘creaming and parking’; for more details, see here, for example). In this instance, it is not difficult to imagine that ‘difficult’ cases – such as those whose files cannot be located or who have changed category – will simply be ignored by Capita.

It should also be noted that the move to use more and more private contractors to sort out the government’s immigration ‘mess’ has gone hand in hand with cuts in the UKBA’s budget and staff. But Capita appears to have already made another mess of it.

Misinterpreted

Another immigration-related mess that Capita has been implicated in recently was the court interpreters contract. In December 2011, Capita acquired Applied Language Solutions Ltd (ALS) for £7.5 million on a cash-free, debt-free basis, with a further “contingent consideration” of up to £60 million over four years. Since 2003, ALS has provided translation and interpreting services to many public and private services, most notably Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunal Service, which includes immigration tribunals; the Crown Prosecution Service; Her Majesty’s Prison Service, including immigration detention centres; and many police forces around the country. The Oldham-based company’s private clients include Google, Sony and Caterpillar.

In August 2011, ALS was awarded a £300 million national contract with the UK Ministry of Justice to run a new Framework Agreement for the provision of all translation and interpreting services to the ministry. The agreement has been in effect since February 2012.

In the first month of the four-year monopoly deal, the company only fulfilled 58 per cent of service requests – against a target of 98 per cent – and received 2,232 complaints in the first quarter of the year. Media reports at the time talked of “courtroom chaos” as court proceedings were being held up or collapsing because interpreters had not shown up or did not have the necessary competence (see here, for example).

Giving evidence to the Commons justice select committee, the former CEO of ALS, Gavin Wheeldon, blamed the failures on interpreters’ “resistance” to the new working conditions. According to one survey, up to 90% of the 1,206 interpreters who worked for ALS under the old system boycotted the new regime because they were unhappy with the dramatic pay cuts and poor travel expenses under the new arrangements.

Capita claims there have been “many recent improvements to the terms and conditions with which we offer interpreters who wish to work with us within the Criminal Justice Sector.” The current rates the company pays are £22 per hour for Tier 1 (specialist, such as those used by courts), £20 per hour for Tier 2, and £16 per hour for Tier 3. But this is still below the standard acceptable rates (see the UKBA’s already-low rates, for example).

Mr Wheeldon admitted his company had relied on “extrapolated” figures to draw up its plans for the MoJ contract but blamed the “serious lack of management information” from the court service about its needs. However, when the new system started, out of the 1,200 specialist interpreters promised, only 280 were available.

The contract, seen by Corporate Watch, states that the contractor, ALS, “shall be responsible for the accuracy of all drawings, documentation and information supplied to the Authority by the Contractor in connection with the supply of the Goods or Services and shall pay the Authority any extra costs occasioned by any discrepancies, errors or omissions therein.”

At a Public Accounts Committee hearing in October 2012, it emerged that senior MoJ officials had not read the credit rating report that they themselves had commissioned, which warned the ministry not to award more than £1 million a year of business to ALS because the company was “too small” to shoulder bigger contracts. The framework agreement is worth £42 million a year.

It is understood that all face-to-face interpreting and document translation are provided by Applied Language Solutions itself, while sign language and telephone interpreting are outsourced to two separate subcontractors.

Inefficiencies and savings

The MoJ claims the contract with ALS will save it £15 million a year. Similarly, Capita boasts that the framework agreement “has been designed to be more efficient and will provide users and taxpayers with a better, more effective service over the term of the contract.” Other ‘benefits’ cited by the company include a single pricing matrix, one point of contact to book services, and a uniform measurement of service usage. The question is: What is exactly meant by ‘efficiency’ and how are these ‘savings’ made?

Following Capita’s acquisition of ALS in December 2011 – which has now been re-branded as Capita Translation and Interpreting and forms a new stand-alone business within the Capita Group – there was a systematic programme of “restructuring and change” taking place behind the scenes. Capita claims this was to supply frontline staff with the “help” they need so that they work “more efficiently and effectively, while allowing departments across the public sector to save money.”

But as we have seen with numerous other private restructuring programmes, in the world of privatisation and outsourcing, efficiency means cutting any ‘extra’ costs, primarily labour costs. Thus, Capita’s “reducing operational inefficiencies” in its new translation business simply meant cutting down on staff, wages, other staff expenses such as transport, social security and so on. The impact on the quality of public services is almost always similar to what we have seen with the court interpreters.

In its Tender Response, ALS promised the MoJ the following: “Our business model is tried and trusted and has delivered significant cost savings to a number of existing customers within the [ministry].” And this is how they did it: the introduction of a “more competitive national environment amongst the interpreters” by abolishing the three-hour minimum payment and only charging for the “actual work done.” “Interpreters that want to make a real career within this sector,” the document adds, “have been extremely flexible, understanding the new economic environment and pushing themselves forward for more professional development and more assignments.”

The company then sites as evidence its “tried and tested methods” used with police forces, which have allegedly delivered “dramatic cost savings and value for money across the board.” These include hourly rate reductions; abolishing the three-hour minimum for interpreting assignments and replacing it with a one-hour minimum, then charging by the minute after the first hour (or by the second with telephone interpreting and by word with translation); lower travels expenses; and technological alternatives to face-to-face interpreting (machine translation, for example).

Interestingly, ALS had anticipated “negative media coverage” of its contract with MoJ: “The UK press may report the annual spend on language services and can report, under the Freedom of Information Act, on payments made to suppliers of these services.” So the cautious company warns the ministry: “It is therefore essential that an agreement statement be in place to use in response to any questions around this topic, which will communicate the efficiencies that the framework agreement will deliver and in turn how these will equate to genuine cost savings for the MoJ.”

Another anticipated risk was the “potential lack of interpreter engagement”: “In the Northwest, we have encountered a group of interpreters who have attempted to resist the outsourcing by the Police Services and have refused to accept assignments via Applied Language Solutions or any other agency.” But it goes on to reassure the ministry: “We do not envisage this causing any problems for the provision of the contract” because, “through targeted recruitment and sponsorship of linguist training, we have fully mitigated this problem.”

The other aim of Capita’s taking over ALS, which had just won the MoJ contract, appears to be establishing a near-monopoly in the public interpreting and translation services market. This, in turn, would make the introduction of drastic measures, such as those mentioned above, easier for the company, as there would not be many competitors that unhappy staff could switch to.

Indeed, according to Capita, the ‘contingent consideration’ of extending the ALS acquisition deal to £60 million over four years is based on “ALS achieving growth targets in line with the successful roll-out of the MoJ contract and greater penetration of the UK language services market.” In a press release, Capita Group’s chief executive said at the time: “By combining ALS’s specialist skills and proprietary technology with Capita’s operational expertise and balance sheet, we believe that this will allow us to become a very strong player in the language services industry. There are excellent opportunities for organic growth both in the UK and internationally.”

ALS had made an operating loss of £0.3 million in the financial year to May 2011, on turnover of £10.6m.

Contractual matters

Given that the MoJ contract with ALS resulted in “total chaos’’ while providing an “appalling” service, to quote the Commons public accounts committee’s report on the fiasco, have any remedial measures been taken by the MoJ against the company?

The framework agreement, seen by Corporate Watch, states that the contractor “shall employ at all times a sufficient number of Contractor’s Personnel to fulfil its obligations under the Contract. All Contractor’s Personnel shall possess the qualifications and competence appropriate to the tasks for which they are employed.” This was clearly not the case, at least in the first few months of the contract, by the company’s own admission.

Under ‘Particular Conditions’ attached to the contract, this is emphasised again: “The Contractor will recruit sufficient numbers of interpreters/translators to provide 24-hour cover 365 days per year. The Authority [the MoJ] cannot guarantee the volume of Service requirements under this Contract.”

In other clauses of the agreement, the contractor should have taken “reasonable care to ensure that in the performance of its obligations under the Contract it does not disrupt the operations of the Authority, its employees or any other contractor employed by the Authority” and should have “satisfied itself that it has sufficient information to ensure that it can provide the Goods or Services” – these being the “timely supply” of interpreters and translators in accordance with the “quality standards” specified in the agreement.

Now, if the contractor failed to provide these services, or provided them inadequately, the agreement states that the MoJ may reduce payment, deduct a sum of money from any scheduled payment due to the contractor or terminate the whole contract. The latter requires the authority to be “of the reasonable opinion” that the contractor is “in default” or “material breach” of the contract and has not “remedied the default to the satisfaction of the Authority within 10 working days” (or such other period specified by the authority). Alternatively, the authority may supply or procure the services somewhere else until the contractor “has demonstrated to the reasonable satisfaction of the Authority that the Contractor will once more be able to supply all or such part of the Services in accordance with the Contract.” The MoJ does not appear to have had the will to take any of these measures.

As far as Corporate Watch is aware, ALS, or Capita Translation and Interpreting, has only been fined £2,200 for “disrupted services.” No other penalties have apparently been levied against the company during the first few months of the contract, when disruption was at its worst. Both Capita and the MoJ declined to confirm or deny whether this is the case.

Furthermore, it can be argued that knowingly disrupting court services for private interest is tantamount to contempt of court. The legal definition of ‘contempt of court’ covers a wide variety of conduct which undermines, or has the potential to undermine, the course of justice and the procedures designed to deal with it.

According to the public accounts select committee, ALS knew it was “clearly incapable of delivering” the MoJ contract, and when Capita took over ALS in late 2011, it “had no hope of recruiting enough qualified interpreters in time to start the service.” Shouldn’t the company and its new owner be held responsible for this?

In its Tender Response submitted to the MoJ, ALS had claimed that 2,500 of its 4,500 registered freelance interpreters were “suitably experienced and qualified” for the MoJ’s needs, and promised its criminal justice services team would “expand considerably to accommodate the requirements of the framework agreement.” It even proposed a service that would “exceed all the key deliverables demanded by the Authority.” It turns out that many of the ‘available’ interpreters had merely registered an interest on the company’s website and had not been subject to any official checks as to whether they possessed the required skills and experience.

Then, there are the ‘lessons’ learnt by government and the assurances that things have now ‘improved’. The justice minister Helen Grant had this to tell us in December 2012: “We have now seen a major improvement in performance – more than 95 per cent of bookings are now being filled, complaints have fallen dramatically and we are continuing to push for further improvement.” Margaret Hodge MP, chair of the public accounts committee, said: “This is an object-lesson in how not to contract out a public service.” Similar lessons were supposedly learnt in the aftermath of the G4S Olympics shambles last year.

As for Capita, in what appears to be an effort to repair the public image of its translation business, the company has been busy with benevolent-looking CSR and PR exercises. For instance, Capita Translation and Interpreting is one of the ‘gold sponsors’ of Translators Without Borders, a charity that provides pro bono translation services to NGOs and relief agencies such as Médecins sans Frontières, Médecins du Monde, Action Against Hunger, Oxfam US and Handicap International.

Translators Without Borders describes its mission (and that of its sister organisation in France Traducteurs Sans Frontières) as “translating knowledge for humanity.” Capita boasts that it is “proud to support Translators without Borders in their efforts to bridge communication and knowledge gaps in some of the most neglected parts of the world, and we are delighted to offer a donation that will go towards the organization achieving their goals.”

—–

In the second part of this article, to be published next week, we will be looking at Capita’s other public contracts in the UK, including those in the immigration and asylum market, and how the government’s drive to outsource public services to the private sector is contributing to the company’s rapid growth.