[responsivevoice_button]

As Mitie becomes the Home Office’s largest provider of immigration detention this month, merging Colnbrook and Harmondsworth into a super-size ‘Heathrow Immigration Removal Centre’, Corporate Watch takes a look at the company’s track record at Campsfield House, the only detention centre it has run before.

Already Campsfield has been marred by a major fire, suicide and three mass hunger strikes since Mitie took over in 2011. So how has Mitie won this new contract, and will asylum-seekers be any safer in their hands?

Mitie, a FTSE 250 outsourcing company, has now started a Home Office contract, worth potentially a quarter of a billion pounds, to detain more asylum-seekers. Ruby McGregor-Smith CBE, chief executive of Mitie, said she was “delighted” to win the contract, and promised: “We will be providing the best environment possible for the people in our care – putting decency, dignity, and safety at the heart of everything we do.” The contract will be run by Mitie’s aptly named ‘Care and Custody’ subsidiary. The company’s press release explained that, “Mitie will care for over 900 immigration detainees providing full centre management, including all custody services, welfare, regime and recreational activity. This partnership will see Mitie becoming the largest single private sector provider of immigration detention services to the Home Office, less than three years after entering the market.”

Despite the PR gloss, Corporate Watch has investigated the company’s track record during its last three years in the asylum ‘market’, and found a catalogue of failures in both safety and care. We have also discovered Mitie’s ability to win the contract was based largely on cherry picking managers from the previous contractor.

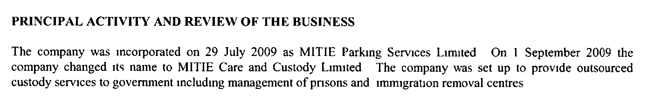

To begin with, we found that Mitie’s ‘Care and Custody’ subsidiary started life as Mitie Parking Services Limited. The company’s accounts (pictured below) show the name was changed after only one month of trading, when, in September 2009, its directors curiously decided not to run anything as mundane as car parks any more, but instead to “provide outsourced custody services to government including management of prisons and immigration removal centres”.

This name change coincided with the arrival of a new director at the car park company, Colin Dobell (pictured left). He came to Mitie from the GEO Group, an American private prison company. Dobell says in his LinkedIn profile that he had “established GEO UK from scratch” in 2005. By the time Dobell moved to Mitie in 2009, GEO had won contracts to run Campsfield and Harmondsworth. Dobell has long been involved in locking up migrants – before GEO, he was commercial director at GSL (now part of G4S) from 2000, which ran Campsfield before both GEO and Mitie got their hands on it.

This name change coincided with the arrival of a new director at the car park company, Colin Dobell (pictured left). He came to Mitie from the GEO Group, an American private prison company. Dobell says in his LinkedIn profile that he had “established GEO UK from scratch” in 2005. By the time Dobell moved to Mitie in 2009, GEO had won contracts to run Campsfield and Harmondsworth. Dobell has long been involved in locking up migrants – before GEO, he was commercial director at GSL (now part of G4S) from 2000, which ran Campsfield before both GEO and Mitie got their hands on it.

2011 – year one: a suicide and a mass hunger strike

With Dobell at the helm, Mitie’s mysterious car parking company soon convinced the Home Office to let it take over from GEO at Campsfield, winning a 5-year contract worth £27 million in February 2011. But how would Mitie be any different from GEO? In addition to Dobell, Mitie’s bid director was Alex Sweeney – who had been GEO’s Centre Manager at Campsfield. These men later made a video about their success as ‘entrepreneurs’.

Mitie’s contract to run Campsfield began on 30 May 2011. Bill MacKeith, a stalwart of the Campaign to Close Campsfield, warned what lay ahead: “Mitie is like other outsourcing companies. They specialise in taking over a service and then squeezing it for profit; finding more ways to exploit staff or cut corners.” Within a week, 23 Iraqi and 14 Afghan detainees went on hunger strike at Campsfield to protest against the government’s plans to deport them to Baghdad and Kabul.

Then, in August 2011, Ianos Dragutan, a 35-year old Moldovan man, hanged himself in a shower cubicle at Campsfield. Liz Peretz, from the Campaign to Close Campsfield, said “This young man’s suicide must immediately raise serious questions about health and safety inside Campsfield, especially the adequacy of health and welfare provision.”She was unequivocal: “Questions need to be asked of both MITIE, the company who won the contract to run the centres earlier this year, and the UKBA [UK Border Agency], who drew up their contract.” Mitie’s centre manager, Paul Morrison (pictured right), said “procedures had been reviewed following the death”. Morrison, a former infantryman and prison service manager, is tipped to run Mitie’s new centres at Colnbrook and Harmondsworth.

Then, in August 2011, Ianos Dragutan, a 35-year old Moldovan man, hanged himself in a shower cubicle at Campsfield. Liz Peretz, from the Campaign to Close Campsfield, said “This young man’s suicide must immediately raise serious questions about health and safety inside Campsfield, especially the adequacy of health and welfare provision.”She was unequivocal: “Questions need to be asked of both MITIE, the company who won the contract to run the centres earlier this year, and the UKBA [UK Border Agency], who drew up their contract.” Mitie’s centre manager, Paul Morrison (pictured right), said “procedures had been reviewed following the death”. Morrison, a former infantryman and prison service manager, is tipped to run Mitie’s new centres at Colnbrook and Harmondsworth. 2012 – year two: another mass hunger-strike

A year after Mitie began running Campsfield, another group of detainees decided that their only means of redress was to go on a mass hunger strike. This time, it was 13 men from the Darfur region of Sudan, including at least one “confirmed torture survivor with visible wounds”, according to Bob Hughes, who visited them in Campsfield. Whilst demanding asylum, the hunger strikers also “complained of their treatment inside the centre, saying that they came here asking for refuge, and instead have been locked up and badly treated.” One of the Darfuri men, who had been detained for two months, had a gunshot wound to the leg, causing chronic pain and walking difficulties. After two weeks of their hunger strike, the men were separated and moved to other detention centres where they continued their hunger strike for several more weeks, as a campaign by supporters on the outside grew. Some of the men were released during the hunger strike.

2013 – year three: a major fire

After two and half year running Campsfield, Mitie could have been expected to have got a grip on the situation. However, late at night on 18 October 2013, due to a lack of safety provisions, a major blaze engulfed the centre. The lives of more than 200 detainees were put in danger, and Mitie’s public reputation was on the line.

The fire occurred when Farid Pardiaz, a 25-year-old detainee from Afghanistan, tried to kill himself by setting fire to bedding in his cell. He survived, but the flames spread to the roof and gutted the main accommodation block. It transpired that there were no sprinklers installed, despite repeated advice from the fire brigade, and despite the fact that Mitie claims to specialise in fire safety. The damage ran to nearly a million pounds, but Mitie refused to comment on whether the company, or the taxpayer, would foot the bill. A parliamentary question eventually disclosed that Mitie would pay up, but still claimed the company had followed all the necessary fire safety regulations.

150 detainees were evacuated from the centre on the night of the fire, and the facility ran at reduced capacity for the next few months. There was only one eye witness testimony given by a detainee on the night of the fire. He claimed Mitie were more concerned with making sure no one had escaped than checking people were not left locked inside.

His claims were broadcast by local and national media. But once the fire was extinguished, the outspoken detainee was pulled from his room at 4am by officers dressed in full riot gear. They dragged him down the corridor (stamping on him as they went) and put him in a segregation unit, where the detainee claims he was beaten up with “one guard trying to choke him for 15 minutes”.

Corporate Watch has seen a letter sent to the detainee by the Home Office Professional Standards Unit that investigated his allegations. It claims “the CCTV camera only covered the outside of the cell” in which much of the alleged assault occurred, which makes it hard to corroborate the detainee’s claims. However, even with these limitations, the report says the “footage shows the officers were inside the cell for nine minutes” using “Control and Restraint techniques”. The investigation concluded that “the reason they spent nine minutes in the Segregation Unit cell” was because the detainee “struggled so much”, to the extent that “the officers had to change over because they had become exhausted” from trying to “control” him.

The ‘investigation’ omits mention of how many officers entered the Segregation Unit. The detainee put the figure at eight, which surely begs the question of what else they were doing besides ‘controlling’ the detainee, and rather supports his allegations of a violent assault. He was then left in the cell for four hours, before being moved to the high-security Colnbrook detention centre.

2014: Mitie rises from the ashes, but detainees still go hungry

The New Year saw a resolution from Mitie and the Home Office to finally listen to the fire brigade and install sprinklers at Campsfield. But it would not receive planning permission until late April, meaning migrants continued to be detained in a building that was manifestly unsafe. And this did not prevent Home Office officials from deciding to increase the capacity of Campsfield from the present 260 to 510 beds, according to Bill MacKeith. And on top of all this, the Home Office awarded Mitie the new contract for Harmondsworth and Colnbrook.

Against this backdrop of stunning ‘success’ for Mitie, Farid Pardiaz, the desperate young man who started the Campsfield fire, was sentenced at Oxford Crown Court to 32 months in prison after pleading guilty to committing arson. Judge Mowat acknowledged that his reasons for doing so stemmed in part at least from they way his asylum claim was being treated: “Mr Pardiaz appeared to have had mixed motives for setting light to bedding in his room, from which fire spread into the roof space of Blue Block at the centre. He had wished both to kill himself and also to show the authorities how strongly he felt that he should not be returned to Afghanistan, where he feared for his life.” The judge, “accepted that Mr Pardiaz had not meant to cause the damage and losses estimated by outgoing centre manager Paul Morrison of Mitie, which runs the centre, as mounting to over £900,000, but she nevertheless had to take the high cost into account in deciding the sentence.”

A member of the Campaign to Close Campsfield, who attended the sentencing, reported that “No mention was made by [the] judge in sentencing or by defence of the fact that Mr Pardiaz had been refused a request to see a doctor in the days running up to the fire, when, as a psychiatric report stated, Mr Pardiaz was experiencing a depressive episode. Nor was it mentioned that very little damage at all would have been caused if the Home Office had carried out the recommendations of the Oxon Fire Service and fitted sprinklers in the centre”.

Not surprisingly, the detainees continue to resist, and in May 2014 another mass hunger-strike was launched, in tandem with fellow inmates at Colnbrook and Harmondsworth. One of the Campsfield detainees told the media, “Our demand is quite simple. We want our freedom. We want our life with dignity. We do not want to be treated in an inhumane way. So that’s why we’re demanding for the closure of all detention centres for immigrants in the UK.” He also called out the “security industry giants” for being behind these detention centres.

When this hunger strike started, supporters gathered outside Campsfield. Acting Centre Manager Andrew Simpson (pictured right) came out to keep an eye on them. He is an ex-navy seaman, who served on HMS Antelope when it was bombed during the Falklands/Malvinas war. It is fortunate the protests inside did not escalate, because unbeknown to the detainees, Simpson had also spent over twenty years in the Prison Service, where he specialised in riot control. He was Deputy Head of the Prison Service’s Control and Restraint (C&R) National Training Centre. Here he rose to be “Head of a national special operations…providing a specialist response to incidents involving Hostage rescue, riot/public order control and rescue/intervention at height.” His expertise ensured he became “Tactical Advisor to Ministers and Senior Managers” where he apparently implemented “the successful resolution of politically sensitive Prison related incidents”, according to his LinkedIn profile. Simpson worked at Campsfield for Mitie from April 2012 to July 2014 (but now works for a bus company in Doncaster). Simpson claims responsibility for developing “new strategies and innovations to promote business transformation and growth” which he evidenced by “the awarding of the Heathrow IRC contract in 2014” which he says will be “the largest IRC in Europe”. He also takes credit for having “Project Managed the successful completion of a major refurbishment of the centre and the installation of a Fire suppression system during 2013 and 2014”, but makes no mention of his company failing to install the sprinklers before it was too late

When this hunger strike started, supporters gathered outside Campsfield. Acting Centre Manager Andrew Simpson (pictured right) came out to keep an eye on them. He is an ex-navy seaman, who served on HMS Antelope when it was bombed during the Falklands/Malvinas war. It is fortunate the protests inside did not escalate, because unbeknown to the detainees, Simpson had also spent over twenty years in the Prison Service, where he specialised in riot control. He was Deputy Head of the Prison Service’s Control and Restraint (C&R) National Training Centre. Here he rose to be “Head of a national special operations…providing a specialist response to incidents involving Hostage rescue, riot/public order control and rescue/intervention at height.” His expertise ensured he became “Tactical Advisor to Ministers and Senior Managers” where he apparently implemented “the successful resolution of politically sensitive Prison related incidents”, according to his LinkedIn profile. Simpson worked at Campsfield for Mitie from April 2012 to July 2014 (but now works for a bus company in Doncaster). Simpson claims responsibility for developing “new strategies and innovations to promote business transformation and growth” which he evidenced by “the awarding of the Heathrow IRC contract in 2014” which he says will be “the largest IRC in Europe”. He also takes credit for having “Project Managed the successful completion of a major refurbishment of the centre and the installation of a Fire suppression system during 2013 and 2014”, but makes no mention of his company failing to install the sprinklers before it was too late

Mitie has clearly built its business in detention centres by recruiting ex-GEO staff and prison service managers. Although this may have helped them win contracts, buying this ‘expertise’ did not stop a series of failures at Campsfield: three mass hunger-strikes, a suicide and a catastrophic fire. How can the Home Office expect a different outcome with this same company now in charge of the much larger and more challenging Colnbrook and Harmondsworth centres? With this track record already at Campsfield, perhaps Mitie should give car parks another chance.

Written by Phil Miller

This name change coincided with the arrival of a new director at the car park company, Colin Dobell (pictured left). He came to Mitie from the GEO Group, an American private prison company. Dobell says in his LinkedIn profile that he had “established GEO UK from scratch” in 2005. By the time Dobell moved to Mitie in 2009, GEO had won contracts to run Campsfield and Harmondsworth. Dobell has long been involved in locking up migrants – before GEO, he was commercial director at GSL (now part of G4S) from 2000, which ran Campsfield before both GEO and Mitie got their hands on it.

This name change coincided with the arrival of a new director at the car park company, Colin Dobell (pictured left). He came to Mitie from the GEO Group, an American private prison company. Dobell says in his LinkedIn profile that he had “established GEO UK from scratch” in 2005. By the time Dobell moved to Mitie in 2009, GEO had won contracts to run Campsfield and Harmondsworth. Dobell has long been involved in locking up migrants – before GEO, he was commercial director at GSL (now part of G4S) from 2000, which ran Campsfield before both GEO and Mitie got their hands on it. Then, in August 2011, Ianos Dragutan, a 35-year old Moldovan man, hanged himself in a shower cubicle at Campsfield. Liz Peretz, from the Campaign to Close Campsfield, said “This young man’s suicide must immediately raise serious questions about health and safety inside Campsfield, especially the adequacy of health and welfare provision.”She was unequivocal: “Questions need to be asked of both MITIE, the company who won the contract to run the centres earlier this year, and the UKBA [UK Border Agency], who drew up their contract.” Mitie’s centre manager, Paul Morrison (pictured right), said “procedures had been reviewed following the death”. Morrison, a former infantryman and prison service manager, is tipped to run Mitie’s new centres at Colnbrook and Harmondsworth.

Then, in August 2011, Ianos Dragutan, a 35-year old Moldovan man, hanged himself in a shower cubicle at Campsfield. Liz Peretz, from the Campaign to Close Campsfield, said “This young man’s suicide must immediately raise serious questions about health and safety inside Campsfield, especially the adequacy of health and welfare provision.”She was unequivocal: “Questions need to be asked of both MITIE, the company who won the contract to run the centres earlier this year, and the UKBA [UK Border Agency], who drew up their contract.” Mitie’s centre manager, Paul Morrison (pictured right), said “procedures had been reviewed following the death”. Morrison, a former infantryman and prison service manager, is tipped to run Mitie’s new centres at Colnbrook and Harmondsworth.  When this hunger strike started, supporters gathered outside Campsfield. Acting Centre Manager Andrew Simpson (pictured right) came out to keep an eye on them. He is an ex-navy seaman, who served on HMS Antelope when it was bombed during the Falklands/Malvinas war. It is fortunate the protests inside did not escalate, because unbeknown to the detainees, Simpson had also spent over twenty years in the Prison Service, where he specialised in riot control. He was Deputy Head of the Prison Service’s Control and Restraint (C&R) National Training Centre. Here he rose to be “Head of a national special operations…providing a specialist response to incidents involving Hostage rescue, riot/public order control and rescue/intervention at height.” His expertise ensured he became “Tactical Advisor to Ministers and Senior Managers” where he apparently implemented “the successful resolution of politically sensitive Prison related incidents”, according to his LinkedIn profile. Simpson worked at Campsfield for Mitie from April 2012 to July 2014 (but now works for a bus company in Doncaster). Simpson claims responsibility for developing “new strategies and innovations to promote business transformation and growth” which he evidenced by “the awarding of the Heathrow IRC contract in 2014” which he says will be “the largest IRC in Europe”. He also takes credit for having “Project Managed the successful completion of a major refurbishment of the centre and the installation of a Fire suppression system during 2013 and 2014”, but makes no mention of his company failing to install the sprinklers before it was too late

When this hunger strike started, supporters gathered outside Campsfield. Acting Centre Manager Andrew Simpson (pictured right) came out to keep an eye on them. He is an ex-navy seaman, who served on HMS Antelope when it was bombed during the Falklands/Malvinas war. It is fortunate the protests inside did not escalate, because unbeknown to the detainees, Simpson had also spent over twenty years in the Prison Service, where he specialised in riot control. He was Deputy Head of the Prison Service’s Control and Restraint (C&R) National Training Centre. Here he rose to be “Head of a national special operations…providing a specialist response to incidents involving Hostage rescue, riot/public order control and rescue/intervention at height.” His expertise ensured he became “Tactical Advisor to Ministers and Senior Managers” where he apparently implemented “the successful resolution of politically sensitive Prison related incidents”, according to his LinkedIn profile. Simpson worked at Campsfield for Mitie from April 2012 to July 2014 (but now works for a bus company in Doncaster). Simpson claims responsibility for developing “new strategies and innovations to promote business transformation and growth” which he evidenced by “the awarding of the Heathrow IRC contract in 2014” which he says will be “the largest IRC in Europe”. He also takes credit for having “Project Managed the successful completion of a major refurbishment of the centre and the installation of a Fire suppression system during 2013 and 2014”, but makes no mention of his company failing to install the sprinklers before it was too late