Company financing

This post is part of Investigating Companies: A Do-It-Yourself Handbook. Read, download or purchase the whole book here.

[responsivevoice_button]

Before companies can start trying to sell their products, they first need to produce them. To do this, they need things like equipment, property, and cash to pay workers and suppliers. The money they need for this is known as capital. Knowing where a company gets this from can help you understand their financial strengths and weaknesses, show who is profiting from its activities, and what claims they have on it.

CAPITAL MEANINGS: Confusingly, capital is sometimes used synonymously with equity, especially for banks. Capital investment, on the other hand, usually means investment in things that will be owned and used for a long period of time, like buildings, vehicles or machinery, rather than short-term costs like paying wages or bills.

DEBT AND EQUITY

Let’s say two friends decide to set up a cake shop. They see it as an investment that they want to make money from, and possibly sell on in the future, so they decide to incorporate it as a limited company, which they both have one share in.

The cake shop then becomes a legally separate entity from both of them. As the two friends want to work there themselves, they make themselves directors.

They’ve already got the recipes for the cakes but before they can make and sell them, they need to buy a building to do that from, an oven to cook them in, a van to deliver them with, then flour, fruit and all the other ingredients they need to make them.

There are two ways the new company can get the capital it needs to get started:

1. The two friends can invest their own money.

2. The company can borrow money, which will probably mean they will have to promise to pay the money back by a certain date, and in the meantime to pay a certain amount of interest every year to the lender.

If the company borrows the money, it would also have to agree that, in the event it can’t pay back the money, the lender would have a claim to an equivalent amount of the cake shop’s possessions and business.

If, for example, the company takes a mortgage from a bank to buy a building to operate from, the bank would probably demand the building as ‘collateral’.

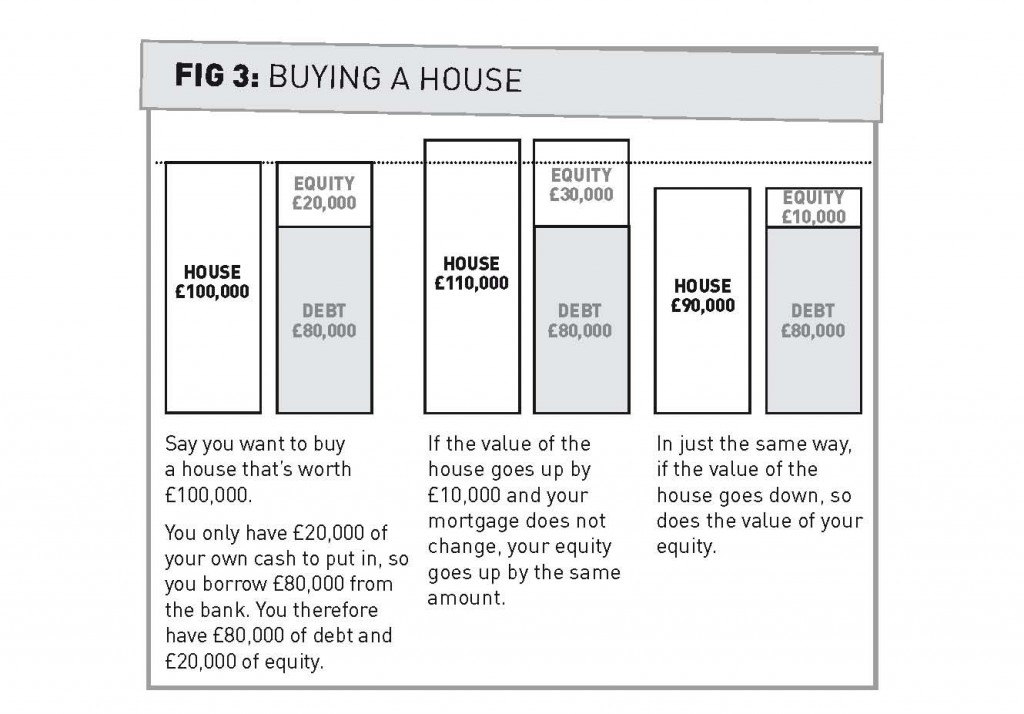

Whoever the company is in debt to therefore has a claim on a proportion of what the company has. Legally, the friends’ shares entitle them each to half of what the company is worth or, put another way, how much it has left after it has paid off its debts. In corporate finance terms, the difference between what a company owns and what it owes – or what the company is worth to its shareholders – is known as its equity.

This will change over time depending on how profitable the cake shop is. If the cake shop sells its cakes for more than it cost to make them, the amount of equity the two friends have a claim to will increase. However, let’s say the oven catches fire and it’s not insured. The company has lost a valuable possession, its debts haven’t changed, so the equity the friends have a claim to would decrease. See Figure 3 for an example involving buying a house.

SECURED OR UNSECURED: Loans made with collateral are called secured. Those without are called unsecured. Paying interest on borrowings is often described as financing or servicing debt.

In general, the more equity a company has compared to its debt, the more financially stable it is. Companies are contractually obliged to pay interest payments whether or not they are profitable, whereas they can only pay dividends to shareholders if they are profitable, and even then the shareholders may decide not to take them (see below). In addition, large amounts of debt make the company far more exposed to external economic changes such as interest rate rises. Companies that have large amounts of debt and relatively little equity are said to have a high debt to equity ratio, or to be highly geared or leveraged. See section 2.6 to find out how much debt and equity a company has.

Note that both shareholders and lenders are investors in the company: they are both putting money into it for a return.

DIVIDENDS

If the cake shop makes a profit, the friends can choose to take out some or all of it out of the company straight away. These pay-outs are called dividends.

They could also choose to leave some or all of it in the business. What they do depends on how they want to expand the business. If they want to keep expanding it and don’t desperately need or desire cash themselves, they may leave the money in so it can be invested elsewhere in the business. If it is invested well, the company’s equity will increase, as will the value of their shares, meaning they can sell them for more in the future. See section 2.6 for how to find how much shareholders have received in dividends in a year.

EXPANSION

At this stage of the cake shop’s life, its behaviour is determined by the two friends, within any constraints set by the terms of the bank loans. But this can soon change. Let’s say the friends’ cake recipe turns out to be a real winner and they want to set up another branch. However, they don’t have enough money yet, so they need to find some outside investment.

Two local investors come along and say they’ll put in enough money to buy a building for the new shop in return for a share in the company each. The two friends decide they’d rather the company take this money than take out another loan with the bank as they don’t want to pay the bank’s interest rates every year. Therefore, they authorise the company to issue two more shares. The two friends now only have a claim to a quarter of the company’s equity each, but they’ve decided that the extra earnings to be made through the new shop is worth losing a proportion of their claim to, and control over, the business.

GOING PUBLIC

The corporate structure gives companies the potential for enormous growth if they can attract the investment. As companies get bigger, the amount of investors who want to buy their shares increases significantly.

Publicly-listing shares greatly increases the amount of potential shareholders that companies can attract, from banks and hedge funds buying shares just to make a quick profit by selling them on the same day, to campaigners buying a single share to protest at the AGM.

Going public often enables companies to grow faster and further, though it also brings increased regulation and can expose companies to the vagaries and hysteria of the financial world.

FLOATATIONS: When companies ‘go public’, or ‘float’ on a stock market (through what’s known as an Initial Public Offering) they will usually issue a certain amount of new shares. The money paid for those shares will go straight into the company (as an equity investment). After the initial offering, the shareholder, not the company, receives the money that they sell their shares for. The total value of a quoted company’s issued shares is called its market capitalisation.

BONDS

The bigger the company, the more investors there are that want it to borrow from them. Instead of taking loans from the local bank, big companies can ‘issue debt’ in the form of multi-million pound bonds.

A bond is basically just an I.O.U. that sets out the terms by which the company will pay back the money it is borrowing, specifying the rate of interest (or ‘coupon’) it will pay and when it will pay the original sum (the ‘principal’) back to whoever ‘buys’ the bond (the ‘bondholder’).

Often, companies will ‘list’ bonds on a public exchange so that they increase the pool of people they can get money from.

Governments also issue bonds as a way of raising finance. The Bank of England has details of government bond rates, which you can use to compare with those of companies.

When someone buys a publicly-listed bond, they can then sell it to someone else, who is said to ‘buy’ the debt from them. This means it is often very difficult to work out exactly who a company owes money to. Often the companies themselves don’t know all the people who own their bonds (though they should know who owns the largest shares). A company’s accounts will usually tell you who gave the company a loan (see section 2.6) but the most you’ll get on bonds is details of the companies or banks that performed insurance or administrative roles when the bond was issued. You could try contacting one of these companies, or the company that issued the bond, and ask if they’ve published the information anywhere. You could also try searching the web for the exact name of the bond. Some institutional investors publish details of their holdings, which may appear in a search.

Credit rating agencies – the biggest of which are Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch – give these bonds ratings, which tend to determine the rates of interest companies have to pay out on them. Bonds rated from the highest rating, AAA, to BBB are classed as ‘investment grade’. This means they are seen as more likely to be repaid and are therefore a safer investment. As a result, companies that issue investment grade bonds have to pay relatively lower interest rates to attract investors to buy them. Anything below BBB is known as a ‘junk’ bond, and is seen as more risky. The companies issuing the bonds therefore have to pay more interest to attract investors.

You might find the interest rates on some bonds or loans are described as being + a certain rate. This just means that the rate specified will be added to the interest paid out. If the interest is described as 3% + RPI, for example, the interest paid out each year will be 3% of the bond’s value plus whatever the Retail Prices Index – a common measure of inflation – is at the time. This is popular as a way of guarding against the effects of inflation.

But even at this scale, the basic principles of corporate finance are still the same. Just like the cake shop, big companies are trying to sell their products for more than it costs to make them, and they can get any extra capital they need through equity or debt financing. And as with the bank and the cake shop, the lenders and bondholders know how much their claim on the company is worth by the value of the loan agreement they have made. The shareholders’ claim changes according to how much is left after the company has paid all its debts.

BUZZ WORDS: The business media likes to get excited about all sorts of bizarre financial shenanigans going on in and around a company. ‘Derivatives’ are used to ‘hedge’ loans, investors ‘short’ shares, while companies issue ‘preferred shares’. You can find out more about these terms with a quick web search. For a critical introduction, see Corporate Watch’s Demystifying the Financial Sector guide.

NOT-FOR-PROFITS: If not-for-profit companies sell their products or services for more than they cost to produce, what they make is called a surplus rather than a profit. This surplus stays in the company as there are no shareholders to distribute it to. If the cake shop was not-for-profit, the two friends could still have paid themselves a salary, but they wouldn’t be able to receive dividends or make a profit from its sale. There are still opportunities for individual enrichment in not-for-profits of course, with some directors of the bigger UK charities and housing associations, among others, earning corporate-level salaries.