Deliveroo: we profile the dodgy delivery firm set to cash in on the stock market

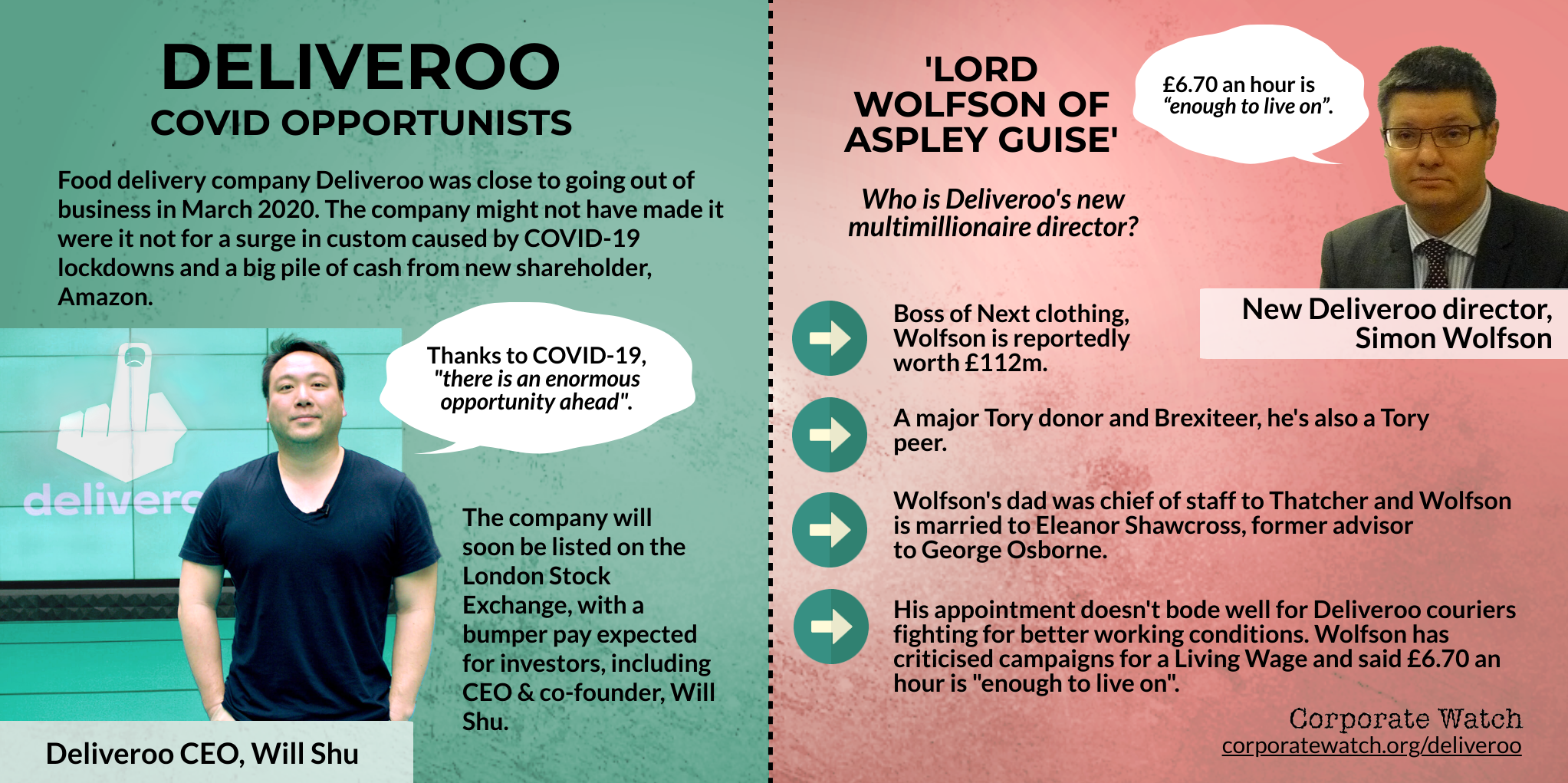

Few companies have had a better pandemic than Deliveroo. Back in March 2020 the food delivery firm was close to going out of business – then came the COVID-19 lockdown and the boom in home deliveries. Capitalising on this, Deliveroo is now preparing to sell its shares on the London Stock Exchange. This should mean a bumper pay day for boss William Shu and the investors who have made big bets on his business. Meanwhile the couriers, on whose sweat Deliveroo depends, continue to be underpaid and exploited.

Over the past four years Corporate Watch has supported Deliveroo couriers with research to help their campaigns for better pay and rights. In this profile we look at Deliveroo’s business model, how it makes money, who’s in charge, its important partners, who is set to benefit from its upcoming stock market splash, and who it needs to please for that to go well. Some stand-out points:

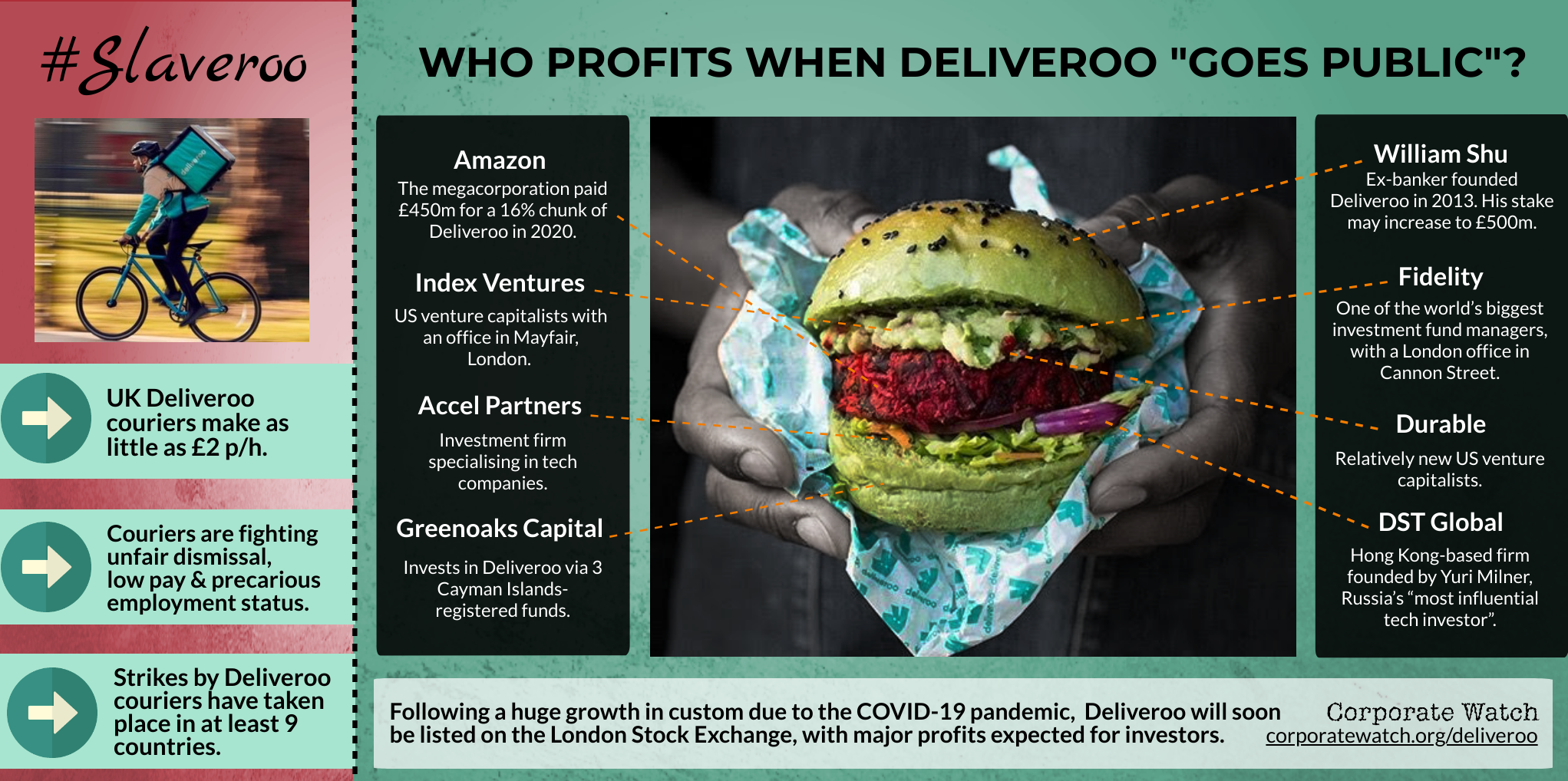

CEO and co-founder William Shu could see his personal stake in Deliveroo rise to £500 million when the company puts its shares up for sale on the stock market this year. Other major Deliveroo shareholders, including corporate giant Amazon, also hope to make big sums.

Meanwhile, Deliveroo couriers continue to struggle with poverty wages and insecure employment. They have taken strike action in at least 9 of the 11 countries Deliveroo works in over the last three years.

Analysis of company accounts suggest Deliveroo was making good money from couriers’ work even before the pandemic and could have afforded to pay them better while still making money from its deliveries. The huge overall losses reported by Deliveroo appear to have been caused by its rapid expansion, a strategy designed to please investors, not riders.

Ahead of the stock market launch Deliveroo has recruited new directors such as Lord Wolfson, multimillionaire boss of clothes chain Next. He has spoken out against the Living Wage and has said £6.70 an hour is enough for workers to live on.

Deliveroo’s biggest partners include restaurant chains Wagamama, KFC and Nando’s, with grocery deliveries for Aldi, M&S, the Co-op and other supermarkets another growing business.

Can we help you look into a company? Click here to get in touch.

Deliveroo couriers in the UK are currently organising and campaigning through the IWGB union’s ‘RooVolt’ campaign. Click here to find out more.

What’s the business?

Deliveroo was founded in 2013 by William Shu, the current CEO, and Greg Orlowski. Customers order food from over 140,000 restaurants and takeaways through its app; Deliveroo sends its 110,000 couriers to pick up then deliver that food, and takes a cut from the orders, plus a delivery fee from customers.

Company propaganda paints Deliveroo’s rapid growth as due to its innovative business model and tech – the efficiency of its ‘Frank’ algorithm for allocating drivers. In reality, its money-making formula is nothing new: it takes as big a cut as possible from the restaurants, while also squeezing workers’ pay to the bone.

On the restaurant side, commissions in the UK can be as much as 35% plus VAT. In May 2020, one pizza restaurant owner told CNBC that Deliveroo’s cut works out at 42% per order when VAT is factored in.

On the other side, the business model means making sure very little of that commission reaches the people who actually deliver the food. Deliveroo has claimed it pays its couriers over £10 per hour, on average, across the UK. Couriers dispute this. A report compiled by MP Frank Field in 2018 found some made as little as £2 per hour once their costs were taken into account. Other common complaints include being classed as self-employed contractors with fewer rights than other workers, lack of safety and protection, job insecurity, and lack of support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Registered under the name Roofoods Ltd, Deliveroo is headquartered in a swanky London office and is active in nearly 800 towns and cities across 11 countries. As well as the UK these are: Australia, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Italy, Ireland, Netherlands, Singapore, Spain, United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. A failed attempt to enter the German market ended in 2019, as the company failed to win sufficient market share against established competitors.

Deliveroo has not yet published information on where it makes most of its money but research firms reckon the UK is easily its biggest market, followed by France, Italy then Spain. Within the UK, the company appears to do the most business in London, followed by Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds. The company delivers from a range of different restaurants but the most important appear to be the big corporate chains – particularly KFC, Wagamama, Nando’s and Burger King (see more on these at the bottom of this profile).

Rise of the dark kitchens

A further twist in Deliveroo’s business model is its use of “dark kitchens”. Also called “ghost” or “cloud” kitchens, these are low-cost food preparation units in industrial estates. The food may be prepared using the recipes, branding and pre-packaged ingredients of a recognised high street chain – without going anywhere near an actual high street restaurant, so slashing the bill for rent as well as front of house costs. As Financial Times columnist Tim Hayward puts it, dark kitchens are “the logical extension of a system that sees food as a manufactured item and replaces hospitality with a supply chain”.

Deliveroo helped pioneer the model in the UK. In June 2017 it had five “Deliveroo editions” sites in London and one in Brighton, hiring out kitchens it had built and equipped to restaurant chain partners. Shu then described the model as the “the biggest development in the market since we first launched”. By the start of 2021 Deliveroo operated 32 of its own dark kitchen sites worldwide, each of which may hold a number of actual kitchens, and it has announced plans to double this number.

Deliveroo is now by no means the only player in the market. Investment capital has piled into the idea in the last couple of years, including funding start-ups such as Karma Kitchen whose whole business offering is to hire out dark kitchen space.

However, there could yet be problems ahead for dark kitchen operators. Many may operate in a grey area without adequate planning permission. Deliveroo has clashed with local authorities over planning and nuisance complaints, and this could become a bigger issue as the sector grows – and possibly provokes resistance.

Worker resistance

In most places where Deliveroo works, there is resistance from its riders. There have been strikes across the UK and court cases around the company’s employment practices. A ‘RooVolt’ campaign by the IWGB union is currently focusing on unfair termination or dismissal, alongside longer-standing grievances over pay and the employment status.

Outside the UK, after a first flurry of transnational industrial action in 2016-17 (click here and here to read more about it), the struggle has been fought on diverse fronts across the world. Since 2018 there have been strikes in Spain, Ireland, Italy,the Netherlands, Hong Kong, France, Belgium and also Germany before Deliveroo pulled out.

Legal challenges to the couriers’ working conditions have been brought against Deliveroo in Spain, Italy, and Australia. In Italy its booking system was deemed “discriminatory”, while the Spanish Supreme Court ruled that couriers are employees, not self-employed contractors. This is similar to a recent Supreme Court decision in the UK concerning Uber, which may also affect Deliveroo in the future.

In addition, there have been some some moves by riders to set up their own courier platforms as a co-operative. This attempt to set up a rider-owned alternative started in France – in the UK, there is currently a branch in York.

Where’s the money?

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a boon for Deliveroo’s finances (see next section). Before the pandemic, Deliveroo was growing rapidly – yet also losing money in eye-watering amounts. Between 2016 and 2019 Deliveroo’s revenues grew sixfold, reaching £772 million at the end of 2019, the last year results are available for. However it posted overall losses of over £100 million in each of those four years: it lost £317 million in 2019.

Deliveroo revenues and losses 2016-2019

£ million | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 |

Revenue | 772 | 476 | 277 | 129 |

Loss after tax | -317 | -232 | -199 | -129 |

Source: Company accounts

This does not mean the company can’t afford to pay its workers better. Look deeper into the accounts and it turns out Deliveroo was making decent profits from its couriers’ work but its desire for international domination incurred huge costs that led to huge losses. This is important as it shows that even after the pandemic restrictions have passed, the business should be generating enough money from couriers’ work to increase their pay.

In 2019, Deliveroo spent £583 million delivering food. According to the accounts, “the largest element” of that spend is “the cost of delivery from restaurants to customers”. In other words, couriers’ pay. Deliveroo’s revenue from those deliveries was £772 million, meaning it made £189 million from deliveries in 2019 (its “gross” profit, in the jargon). After barely breaking even from deliveries in 2016, the profitability of its deliveries has been strong every year since 2017. Given the boom to Deliveroo from the pandemic and the increased cuts it can take from restaurants, this will likely have increased again in 2020.

£ million | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 |

Revenue | 772 | 476 | 277 | 129 |

Cost of sales | 583 | 385 | 213 | 127 |

Gross profit | 189 | 91 | 64 | 1 |

Gross margin | 24% | 19% | 23% | 0.01% |

Source: Company accounts

So if Deliveroo has been making decent money from its deliveries, why has it been making such huge losses overall? The accounts say its poor overall results came “principally as a result of the Group’s focus on investment, given it is still in a rapid growth and expansion phase”. The extra costs caused by this expansion are grouped together in “administrative” expenses. They peaked at a massive £502 million in 2019 but have been high throughout Deliveroo’s existence.

£ million | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 |

Administrative expenses | 502 | 346 | 244 | 142 |

Source: Company accounts

These numbers will include some costs essential for the running of the business. The wages of software engineers running and maintaining the app, for example, or other workers employed in head office or other administration and a variety of other admin costs. But it is the costs of Deliveroo’s investment in its rapid expansion plan that appears to be causing the real damage to the company’s overall results. In just a few years since starting in 2013, Deliveroo has muscled its way into at least 13 countries and has set up a range of new business lines. That does not come cheap. Neither does failure: the 2019 admin expenses included a £43.4m “impairment” charge after it shut its operations in Germany and Taiwan.

The cash it used for this expansion has come from confident investors who have ploughed money into the company to push up its market value. But it has also come from the profit Deliveroo made from deliveries, generated by squeezing its couriers’ pay to a minimum.

Thank you Amazon and COVID-19

At the start of 2020, things were not looking great for Deliveroo. It seemed like Shu might have pushed his rapid growth strategy too far: delivery profits had grown, but expansion costs and so overall losses had grown even more. To keep going, Deliveroo needed more capital. It turned to the global platform capitalism behemoth Amazon, which in 2020 bought a £450 million chunk of Deliveroo, becoming the company’s biggest shareholder with a 16% stake.

The controversial deal was initially mooted in May 2019, but then blocked for a year by the Competition and Mergers Authority (CMA). They feared that even as a minority shareholder Amazon could wield “material influence” on Deliveroo and seriously impact competition in the delivery industry due to its massive market power. But in 2020 the CMA eventually backed down and agreed the deal – after Deliveroo convinced the authorities that it would indeed go bust without Amazon’s help.

Then came COVID-19. In the words of Will Shu, the pandemic has “accelerated strong underlying trends, and there is an enormous opportunity ahead”, After a rocky couple of months, restaurants opened up again and more people ordered meals to eat at home.

Buoyed by its new success, Deliveroo has played hardball with restauranteurs who have dared play away with any of its rivals. One London restaurant told the Financial Times that Deliveroo threatened to increase its commission after the restaurant also sold through UberEats. Deliveroo also struck deals with supermarkets to deliver groceries ordered through the app. The company now delivers for Aldi, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s and Waitrose.

Thanks to this, Shu announced in December his company was signing-up more customers, seeing existing customers place more orders, and seeing the average value of orders grow. All this helped it make its first ever operating profit in the first six months of 2020.

In short, COVID appears to have boosted revenue so much that the huge ‘admin costs’ are finally outweighed by increased sales. Again: this undermines any justification Deliveroo may give for not paying its couriers better. It has the money and can afford to do it.

The IPO

Thanks to its COVID boost, Deliveroo is now planning to ‘list’ its shares on the London Stock Exchange. The ‘Initial Public Offering’ (IPO) was officially announced on Monday.

Until now Deliveroo’s shares have been traded privately: the company has solicited money from specific investors, then given them shares in return. By ‘going public’, Deliveroo will issue new shares through the stock exchange, which greatly increases the number of investors it can reach. This should bring a huge amount of cash into the business – as Deliveroo will receive the money paid for the new shares.

It also means a potential bonanza for William Shu, Amazon and its other current shareholders, with increasing demand pushing the value of their stakes higher. We don’t know how much investors will decide Deliveroo is worth for the IPO but the company is reportedly targeting a valuation of £7 billion. This would make Shu’s stake worth around £500 million.

While individual investors will be able buy Deliveroo shares after the IPO, the biggest prize for corporations are the ‘institutional’ investors: huge investment firms that manage trillions in savings and pensions, many of which can only be invested in shares listed on a stock market. A look at who now owns rival Just Eat shows some of the firms that may be interested: Blackrock, Vanguard, Standard Life and other mainstays of global capitalism.

The more they like Deliveroo, the higher Deliveroo and its banks can set the share price (and the higher it is, the more money it can generate). Potential institutional investors will not be concerned about the ethics of Deliveroo’s business model – but they may be put off if they think workers’ challenges will be successful.

Deliveroo has already signed-up JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs and other investment banks to take care of proceedings and will currently be marketing itself directly to institutional investors to drum up demand. A next step will be to issue a ‘prospectus’ that will present the business to potential investors and should contain a lot of new information about the workings of the company. It should also identify any “material risks” that could cause problems for its business model.

This has to be signed-off by the state regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority. Will it insist Deliveroo list legal cases around workers’ rights or resistance as material risks? Let’s see, but given the government is currently trying to lure future tech companies’ IPOs to London, don’t expect too much.

Size wars

What is Deliveroo’s plan to impress potential investors this year? The company can’t bank on COVID lockdowns being around for ever – so can it use the current momentum to find more sustainable long-term profit?

Deliveroo’s biggest market is the UK. But it is not alone and is a long way from dominance. Its two main rivals are Just Eat and Uber Eats. Uber has a wide network and partnerships with major restaurant chains, while Just Eat’s app is still the most popular app for orders. Just Eat has also recently developed its own courier fleet (restaurants on its app previously had to arrange delivery themselves). Neither are short of cash to grow their businesses further. Ominously for Deliveroo, Just Eat’s CEO Jitse Groen issued a declaration of war earlier this year, announcing his company will “go all out” against Deliveroo and Uber Eats, with dominating London a particular focus.

There are also other up-and-coming players challenging Deliveroo: for example, dark kitchen specialist Karma Kitchens, which has a partnership with Uber Eats, raised £252 million in 2020 to massively expand its network.

In response to this competition, Deliveroo’s strategy appears to be simple – keep bulking up. So far in 2021 it has announced the following plans to expand its operations:

Grow across the UK, with more restaurants and chains on its app. In January 2021 Deliveroo said it plans to cover 100 new towns and cities.

More dark kitchens – plans to “more than double” the number of its ‘Editions’ sites worldwide in 2021 (there are currently 32, containing over 200 kitchens).

More “on demand grocery” partnerships with supermarkets – the “fastest growing part of the business”.

It goes without saying that another key part of the strategy will be to continue to challenge any attempts by its workers to increase their pay.

Who runs Deliveroo?

Deliveroo is led by William Shu, who is also its co-founder (the other, Greg Orlowski, has since left the company). Shu used to work for investment bank Morgan Stanley. The Deliveroo origin story tells of Shu dreaming up the company while working late nights in the London office, where his number-crunching was interrupted by having to leave his desk to pick up food.

Also on the board is Deliveroo’s head bean-counter, Adam Miller, who was appointed as Chief Financial Officer last year. He used to be an executive at the travel business, Expedia.

The rest of the board are either representatives of existing shareholders or big corporate ‘stars’ hired to impress potential investors for Deliveroo’s big stock market opening.

Deliveroo signed Claudia Arney, Richard ‘Rick’ Medlock and Simon Wolfson last year and the company hopes they will all polish its image with investors – and thereby increase the cash it hopes to raise.

Medlock has a background in finance and is former Chief Financial Officer at Worldpay, a payment processing firm. Medlock was CFO at telecomms firm Inmarsat for nine years, where he oversaw its initial public offering.

Arney has a more impressive corporate CV: she has worked for Pearson, the Financial Times, Goldman Sachs, HM Treasury and has experience as a director at Ocado, Halfords, property firm Derwent London, Aviva, Which? and TFL. She was previously interim chair of the Premier League.

She will need to balance her commitments at Deliveroo with her directorship at Kingfisher plc, a large DIY retail group whose name is less familiar than its brands: B&Q, Castorama, Brico Dépôt and Screwfix. She is also currently a director of Bedales school, a boarding school in Hampshire. Bedales boasts an impressive list of alumni including Cara Delevingne, Daniel Day-Lewis and Lily Allen as well as knights, nobles and royals.

But perhaps the biggest signing is Simon Wolfson. Currently the CEO of Next, Wolfson is the FTSE 100’s longest-serving chief executive (when appointed in 2001, he was also its youngest). A Tory peer, ‘Lord Wolfson of Aspley Guise’ is the ‘scion of a well-known retail family’ and is reportedly worth an estimated £112m.

Wolfson is no stranger to Deliveroo’s key business strategy of squeezing worker pay. In 2015 he made headlines by criticising campaigns calling for firms to pay a Living Wage of £7.85 an hour. He said £6.70 an hour was “enough to live on” for a lot of people.

Wolfson has given serious financial backing to the Conservative Party and to Brexit. He has personally donated £630,850 to the party and to David Cameron, plus another £100,000 to the Vote Leave campaign. He has also been Chairman of Open Europe, a Eurosceptic research and propaganda outfit that merged with Policy Exchange, a powerful Tory think tank of which he is now a trustee.

Wolfson has further Tory connections through his family. He is married to Eleanor Shawcross, a Non-Executive Director at the Department for Work and Pensions, and former economic advisor to George Osborne. His father, David Wolfson, is a businessman and former chief of staff to Margaret Thatcher who was also raised to the peerage as Baron Wolfson of Sunningdale – though later kicked out of the House of Lords for non-attendance.

Some Next shareholders are reportedly none too happy with Wolfson’s new appointment at Deliveroo. They are worried the role will distract him from his duties at the fashion retailer at what seems a crucial time for the company. Some insiders reckon he wants the Deliveroo post as a way to get closer to Amazon, his ultimate target destination.

Aside from Next, Wolfson currently has shareholdings in the following companies: Superdry clothing, biotechnology firm ADC Therapeutics, Pembroke Venture Capital Trust, and nuclear fusion research company Tokamak Energy.

Also on the board is Darrell Cavens, an entrepreneur and founder of Zulily, an ‘e-commerce company’, who joined Deliveroo in 2017. The rest of the directors all represent current shareholders:

Antoine Froger, representing Bridgepoint. He also currently sits on the board of Burger King’s France franchise, another of Bridgepoint’s investments.

Martin Mignot, representing Index Ventures, one of Deliveroo’s earliest backers. A keen cyclist, he recently collaborated with London Cycling Campaign on a webinar about how to make London a ‘friendlier and safer for pedestrians and cyclists’. He has 45,000 followers on Twitter where he uses hashtags such as #humansnotcars.

US-based Jayant Mittal, representing Amazon, where he is a Corporate Development Director.

Benjamin ‘Benny’ Peretz, representing Greenoaks Capital.

Seth Pierrepoint, representing Accel. Pierrepoint is described as having played a key role in Accel’s early investment in Deliveroo.

Adam Valkin, representing venture capitalist firm General Catalyst. He posts about his business on Twitter.

Who owns Deliveroo?

Co-founder William Shu still owns a fair chunk of Deliveroo’s shares – 6.8% as of January 2021. His former partner Greg Orlowski also keeps a stake, possibly now around 2%. However, most Deliveroo shares are owned by investment firms – both big global investors and more specialist private equity funds – as well as the megacorporation Amazon.

As discussed above, Deliveroo never made a profit until COVID. It is only still in business thanks to being given piles of cash by these investors. They are betting that the value of their investment will increase and make them handsome profits if the coming IPO is well received by the stock market.

The current shareholders are:

Amazon

The delivery and cloud computing leviathan is now one of Deliveroo’s largest shareholders, and has a seat on the board. In 2020 it bought a £450 million chunk of Deliveroo in a controversial deal which at the time gave it a 16% stake – after a year of wrangling with the Competition and Mergers Authority (CMA). Amazon was fined £55,000 for failing to provide timely information during the competition inquiry – an amount that will mean little set against its multi-billion dollar profits.

Amazon’s intentions with Deliveroo are an interesting question, given its massive wealth and drive to dominate most of the markets it enters. One analyst speculates that the endgame may be eventually combining Deliveroo’s food-ordering app into an Amazon “super app”. Or perhaps Amazon could use the business knowledge it gains from Deliveroo to launch its own dark kitchen operations in other countries.

Just last month (Janary 2020) Deliveroo topped-up its capital by selling another $180 million in shares. The sale was led by two investment managers – Fidelity and Durable. It is not yet clear how many of the shares they kept for themselves, and how many they sold on to other existing investors. Fidelity is one of the world’s biggest investment fund managers, based in the US with a London office in Cannon Street. In June 2020 it managed assets of over $3.3 trillion.

Durable is a venture capital fund based in Maryland in the US. It was set up recently in 2019 by Henry Ellenbogen, a former “star fund manager” at big investor T. Rowe Price – which also owns shares in Deliveroo.

US venture capital firm, putting its money into Deliveroo through two Jersey registered investment funds (essentially pots of money). Invests in 160 companies in 24 countries, including: Dropbox, Etsy, Sonos, SoundCloud, Squarespace, Lookout, Hortonworks, Pure Storage, Funding Circle, as well as Deliveroo rival Just Eat. Its London office is in Mayfair, naturally. Represented by Martin Mignot on the Deliveroo board.

Hong Kong-based firm founded by Yuri Milner, Russia’s “most influential tech investor” according to Forbes. It is one of the world’s most successful internet company backers after making huge sums from stakes in Alibaba and Facebook. It invests in Deliveroo through three different funds. It has a London address in Mayfair.

San Francisco-based venture capitalists specializing in tech investments. They invest in Deliveroo through three different funds, all of which appear to be registered in the Cayman Islands. They are represented by Benjamin Peretz on the Deliveroo board.

Another investment firm specializing in tech companies. They were one of the first investors in Facebook and also own stakes in Dropbox, GoFundMe, Groupon, GoCardless, Squarespace, Walmart.com, Wonga and a host of other companies. They have a UK office in Mayfair, London.

US-based venture capital fund manager that invests particularly in “growing” tech companies. Has also backed Airbnb, Snapchat, among others. Represented on the board by Alexander Valkin.

Deliveroo’s key restaurant and grocery partners

Nando’s

Nando’s deliver exclusively with Deliveroo and have recently expanded the amount of restaurants on the Deliveroo app.

Nando’s is owned by Dick Enthoven, a South African billionaire who owns the company through a string of offshore companies. His son, Robby Entoven, heads the UK operation of Nandos.

Burger King

Burgers were the most popular Deliveroo order during the UK’s COVID lockdown, and Burger King has been ramping up its delivery business.

Burger King worldwide is owned by Restaurant Brands International, a massive Canadian-American company. The Franchise to operate Burger King restaurants in the UK is owned by UK-based private equity investment firm Bridgepoint Capital, which is also a Deliveroo shareholder.

KFC

KFC and Deliveroo’s relationship extends to holding joint publicity stunts together. KFC is another COVID winner, expanding business during the pandemic: they have recruited almost 10,000 new staff by the end of 2020.

KFC is part of major US company Yum! Brands Inc, which also owns Taco Bell and Pizza Hut. Pizza Hut also used Deliveroo, though is testing its own delivery options. Yum! Brands Inc Previously invested $200m in GrubHub. In the UK KFC’s restaurants are run by 37 franchise partners, who range from small family owned businesses to bigger franchise companies that run multiple outlets.

Wagamama

Wagamama was already expanding via “Dark Kitchens” before the pandemic in early 2020. It cited strong courier operations as part of its “covid resilience” strategy for the future in its annual report.

Wagamama is part of The Restaurant Group Plc, whose other restaurants include: Chiquito, Frankie & Benny’s, TRG Concessions, Brunning & Price, Coast to Coast, The Filling Station, Fire Jacks, Garfunkel’s, and Joe’s Kitchen. Not all of the group’s brands have done so well: during the Covid-19 outbreak and subsequent quarantine, The Restaurant Group closed 250 restaurants, with a loss of nearly 4,500 jobs.

Five Guys

The “Golden Burger” marketing stunt with Deliveroo that amounted to £25,000 worth of cash prizes shows the effort that has gone into marketing Five Guys on Deliveroo. There’s also evidence of the chain growing in the UK despite the pandemic. As a highly successful burger chain, and burgers being named the most popular take away during the pandemic, it’s safe to assume that Five Guys is an important partner to Deliveroo.

Five Guys internationally is owned by the US-based Murrell family. The UK operation is owned jointly by the Murrells and Freston Ventures, an investment company run by Carphone Warehouse founder Sir Charles Dunstone.

The Co-Op

The Co-Op has paid for TV ads to promote its partnership with Deliveroo. It has become the most “widely available supermarket on Deliveroo” with 400 stores now available.

The Co-Op is technically still owned by its five million members: anyone can become a member by subscribing for a £1 share. Co-Op members vote on motions at the AGM and also elect the members council which consists of 100 members from across the UK.