Elephant & Castle shopping centre: the battle at London’s gentrification “ground zero”

The Elephant and Castle has been called London’s gentrification “ground zero”. In a just a few years the area has been transformed beyond recognition – from a bustling neighbourhood of council estates and street markets, to a spike of high-income glass skyscrapers owned by offshore investors.

The developers’ next target is the shopping centre in the middle of the area. The complex’s architectural beauty is debated – 1960s design icon to some, concrete carbuncle to others. But it’s undeniably a living heart of a diverse working class neighbourhood, with its many Latin American shops and cafes, street stalls, a popular bingo hall, and the nearby Coronet venue.

All this is set to be demolished and “redeveloped” by property investor Delancey (see our profile of the company here). Delancey is also responsible for the Elephant One tower next door: a luxury housing development with zero “affordable homes”, involving massive profiteering through offshore tax havens. In the new shopping centre scheme, too, Delancey has used every possible trick to minimise its commitments to local people.

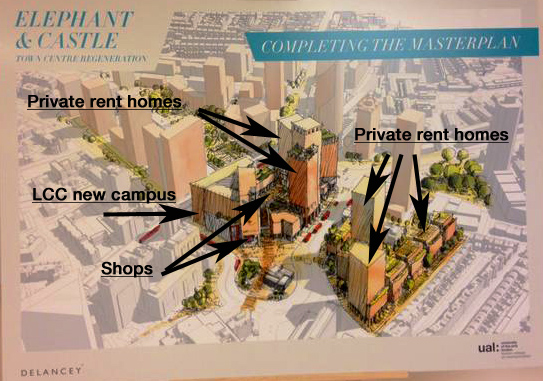

In July 2018, Southwark Council finally gave planning permission for Delancey’s new scheme – after sustained local resistance had helped defer it several times. This will see the shopping centre replaced with 979 apartments – only 116 of them for “social rent”. There will also be offices, a new campus for the University of the Arts (UAL) London College of Communication, and retail space – but little of it for the existing shopping centre traders. Of the businesses located in and around the site, 36 have been given a ‘relocation offer’. But more than twice as many have been left facing enforced downsizing or eviction and displacement.

The developers want bulldozers in by the end of this year. But traders and campaigners haven’t given up their fight. They are now challenging the planning decision in a judicial review. They aim to ensure the centre stays serving the locals that need and use it on a daily basis.

The judicial review hearing is now set to take place this week: on 17 and 18 July, at the Royal Courts of Justice in The Strand.

NB: see also this detailed report by the 35% campaign for more information on the shopping centre plan.

Who’s involved?

Who’s making the key decisions about the Elephant and Castle shopping centre development? And who’s profiting from it? Here’s a list of some of the main players:

- The developer: Delancey. Will oversee the development, and rent out the new private homes through its “Get Living” joint venture company.

Behind Delancey are a number of big money backers. These include the following investors who own the site in a partnership with Delancey:

- The ruling family of Qatar;

- Dutch pension fund manager APG;

- Oxford Properties, real estate company of the Canadian pension fund OMERS.

- Kintyre Corp – a property investment vehicle registered in Panama and named in the Panama Papers.

We zoom in on Delancey and its partner investors in our company profile report.

But as well as these direct profiteers, the scheme would not be possible without the cooperation of other key partners including government bodies.

- Local government: Southwark Council, under its Labour party leader Peter John. Has supported Delancey’s plans and granted permission for the scheme.

- Local government: the Mayor and Greater London Assembly. The Mayor of London has a “strategic planning” role across London and is able to block planning permission for controversial schemes. In December 2018, he supported Southwark council and refused to intervene.

- Key business partner: The University of the Arts – London College of Communication. Will have a new campus on the developed site. Local campaigners say is effectively “artwashing” the development, and helps by lobbying hard for the scheme to go through.

- Other partners include Tree Shepherd – a consultant employed as an “independent business and relocation advisor”, helps encourage market traders to move out without a fuss. (See report by Southwark Notes.)

Potted history

The redevelopment of the shopping centre has been in the pipeline since 2002. Former owners St. Modwen Properties wanted to build housing on top of the site and to refurbish rather than replace the shopping centre. However, the financial crisis and disagreements with Southwark Council meant that the funding was never achieved nor permission granted for the plans. St. Modwen sold the site to Delancey in 2013 for £80m.

See here for a detailed timeline of all Elephant and Castle gentrification projects.

Key Issue: social cleansing of Southwark

The Shopping Centre lies at the heart of the controversial ‘regeneration’ of the entire area. According to the official Elephant and Castle partnership” there are 21 “core” projects “either underway or in the pipeline”. The biggest developments include, besides the shopping centre:

- Elephant One. A tower block complex next to the shopping centre, already built by Delancey. Infamously contains zero “social” housing, breaking Southwark Council pledges.

- Elephant Park (former Heygate Estate). In 2013, the 1194 council homes on the Heygate Estate were demolished after years of resistance and delays. These are now being replaced by shiny tower blocks that contain less than 100 ‘socially-rented’ homes out of more than 2500 new flats. The developer is Australia-based corporation Lendlease – see here for our detailed profile of the company.

- Aylesbury Estate. Once London’s biggest housing estate, which originally contained 2700 council homes. Southwark council has been scheming to get rid of its residents for more than 20 years. The latest plan involves demolishing what’s left of the estate for a new development led by Notting Hill Housing, with much reduced social housing. But some tenants and leaseholders are still holding out …

Taking these together, the Elephant and Castle is one of the UK’s biggest “regeneration”, or social transformation, schemes. The built environment and day-to-day experiences are being reshaped by the flows of global capital, prioritising investors’ profits over the needs of the people who actually live and work in those places. Face-to-face trade and community space are replaced by luxury living, retail chains and privatised plazas.

In a March 2012 Equalities Assessment Paper, Southwark Council itself recognised that:

The regeneration of Elephant and Castle may result in a rise in house prices and housing may become unaffordable to those currently living in the area, especially for, lone parents, disabled people, the BME community and elderly people. This may also result in a dilution of the community as people are forced to move out of the area as they no longer can afford to live there.

Of course, this is yet another example of ‘social cleansing’ in London: poorer and/or ethnically diverse communities priced out of the area, as a new more affluent class of resident and consumer moves in. In the “Heygate diaspora”, as the 35% campaign has shown, tenants were scattered far from the demolished estate, with only one in five rehoused in the SE17 area. Since 1997, more than 135,000 poorer London residents have been forcibly displaced by similar schemes.

Profits and tax avoidance

But some other people are doing very well out of this “social cleansing”. Typically, Build to Rent schemes like the one Delancey is proposing may make a 7.5% annual return on investment. This may be lower than the profit on a more traditional “Build to Sell” development. However, it’s a long-term investment, with much less risk to the developers and profits flowing reliably over a number of years.

Where will those profits end up? In the case of the Elephant shopping centre, all profits generated from the ‘Build to Rent’ properties to be managed by ‘Get Living’, a Delancey joint venture, will fly off to Qatar, Holland, Canada, and the pockets of the super-rich. A complex web of tax haven companies will be used to make sure the minimum of that goes to the UK public. Get Living is already bringing in £35 million in rental income a year from its London flats. (See our Delancey company profile for more details.)

Delancey’s vision for the shopping centre development

What about social housing?

One of the main arguments politicians and developers use to push through schemes is the need for more housing. But whose housing? The Elephant developments so far have been overwhelmingly for private sale or rent, often marketed at rich overseas buyers.

Officially, Southwark Council has a policy of 35% “affordable housing” in new developments, with half of that dedicated to ‘social rent’ – the supposed equivalent of council housing. But it has routinely allowed developers to flaunt this. In reality in the 5 years to 2017, only 28% of new units were ‘affordable’ across the Borough, and under half of these were social rent. Delancey’s Elephant One scheme got away with zero social housing.

The developer’s original plans for the shopping centre development were also pitiful – with 33 homes for “social rent”, out of 979 flats. Local campaigning has managed to push them back on this to some degree. The latest plans include 116 homes for Social Rent, including 28 three-bedroom homes. There will be another 214 on intermediate or so-called “affordable” rents – i.e., slightly below open market levels, but still far from affordable for the majority of local people.

This concession has been hard won by campaigners. But it is still below Southwark’s official targets – and a drop in the ocean considering the thousands of council homes lost on the Heygate and Aylesbury Estates.

Also, campaigners remain unconvinced about when and if the ‘socially-rented’ homes will actually be built. The details of the planning agreement say they will only be built if the second phase ‘West Side’ of the development goes ahead, which may not happen for another ten years.

What about local businesses?

There are over 100 active businesses on the site. The development promises 500,000 square feet of retail space – an increase on the 327,000 sq ft in the current shopping centre. And yet most of the existing traders are being evicted with no guarantee of new space.

After fierce campaigning by local traders and supporters, the council’s January 2019 planning agreement made Delancey include a “relocation strategy” to “mitigate the impact” of the development. The developer is supposed to put aside a fund of £634,700 for business relocation.

However, at the time of writing, only 36 businesses have been made “relocation” offers. Many others will be left with nothing.

And many have already been pushed out. The shopping centre is becoming a ghost town, with Delancey and their partners – managing agent Savills, and consultant “relocation partner” Tree Shepherd – already busy emptying the building.

For example, tenants of Hannibal House, the offices above the centre, were evicted in Summer 2018. Many of these were charities and other non-profits that serviced the local community, such as grassroots trade union United Voices of the World.

By the end of March 2019, London Palace Bingo had closed its doors for the last time. A popular community space, the bingo was enjoyed by 7500 people a week. Nearly half of its customers were over 65 years old and nearly two-thirds were of black African or Caribbean descent. This comes on top of the closure of the Charlie Chaplin Pub and the Victorian nightclub/ theatre venue the Coronet. Other businesses are either upping sticks or haemorrhaging money because of the uncertainty over their future.

Other businesses. such as established Latin venues La Bodeguita and Distriandina, have been offered relocation — but on worse terms. These will lead to a significant decrease in the size of their businesses, as well as their potential closure as nightclubs and music venues, something which would be hugely damaging for London’s Latin American community.

Some traders have now accepted the relocation package on offer from Delancey and their ‘partners’. This includes discounted rents on premises located around the main the site at Castle Square, Perronet House and One Elephant. However, the move comes at a cost even to them. Most are being forced to downsize, with a net loss overall of 4,000 square metres of trading space.

The Campaign

While Southwark Council are hand-in-glove with Delancey, local people have been organising and fighting back on the ground. The Elephant and Castle shopping centre is a prime example of how a strong, organised local community can push back against top-down profit-seeking redevelopment plans, even if it has not yet succeeded in getting the scheme scrapped in favour of a more locally-aware and human-centric scheme.

The ‘Up the Elephant’ campaign emerged to challenge plans for the Shopping Centre on the:

- small number of homes available for ‘social rent’ (the private equivalent of council housing),

- failure to mitigate the impact on the ethnically diverse community that use the shopping centre, for example, it is a focal point for London’s Latin American population

- inadequate provision in the plans for the many small businesses currently located on site.

It is formed of a loose coalition of organisations including:

- Southwark Notes

- Elephant Amenity Network / The 35% Campaign

- The Latin Elephant

- Southwark Law Centre

- Southwark Defend Council Housing

- Elephant and Castle Traders Association

- Stop the Elephant Development – UAL student campaign.

All is not yet lost: judicial review and the ongoing campaign

The campaign is currently focusing around a judicial review to try and get the planning approval overturned.

As the campaigners sum up:

The case for quashing the planning approval is that Southwark Council’s planning committee was misled about the maximum amount of affordable housing that the scheme could viably provide. Delancey said it could only afford to provide 116 social rented units, but we now know that with the Mayor’s funding they could give us another 42.

The legal challenge was launched in March 2019. It is supported by the Public Interest Law Centre and Southwark Law Centre.

A judicial hearing is now set to take place on 17 and 18 July, at the High Court in the Strand.