Eurotunnel: death at the fences, profits for Goldman Sachs

[responsivevoice_button]

At least 15 people were killed in or around the Channel Tunnel in 2015, trying to get past the militarised border. Meanwhile, Eurotunnel made a record €100 million profit, almost all paid in dividends to Goldman Sachs and its other shareholders.

A report by Corporate Watch and Calais Research Network.

At least 15 people were killed in or around the channel tunnel in 2015. Some were electrocuted, some run over by trains, some chased by police into traffic near the entrance. All these deaths were a direct result of people trying to get past the intensive security put in place by Eurotunnel, funded by the British and French governments, to stop them reaching England.

Responding to these deaths, Eurotunnel apologised for the inconvenience caused to its passengers. Its boss Jacques Gounon explained that the migrants dying at his door are “very far from poor unfortunates who seek refuge in England and have a right to a humanitarian approach”, but instead are “veritable commandos, well coordinated” who seek “to make politics and destabilise the government.”

Also in 2015 Eurotunnel, which runs the tunnel under a concession lasting until 2086, made a €100 million profit. €97 million of this was paid out as a dividend and handed straight to its shareholders, international investment firms led by major shareholder and creditor Goldman Sachs. Despite this record year, Eurotunnel is demanding millions more in compensation from the governments for “lost earnings” due to the “migrant crisis”.

But just what is the Eurotunnel company, and how has it come to play a key role in the militarisation of the UK/France border? This report profiles the company’s business and growth strategy; its owners, decision-makers, and powerful political connections; its history and crucial role in the border system at Calais; and some issues for its future development.

Contents

Key Points

The Tunnel

Business Overview

History of Eurotunnel

Eurotunnel and Border Security

Eurotunnel vs. Migrants

Greenwashing

Investors

Key People: board and executives

Challenges for the future

Key Points

- Eurotunnel has played a key role in the militarisation of the border from the start. The treaties that originally exported the UK border to France, bringing a new world of barbed wire and police patrols to Calais, emerged from negotiations around the tunnel. The governments outsource border security to the company, handing over tens of millions to fund a 300 strong private security army headed by an ex-police chief and ex-army colonel, and to install an array of surveillance and security technologies.

- Eurotunnel is where political, financial, and military interests come together at the heart of the Calais border system. Directors include politicians from both sides of the channel, including disgraced British ex-ministers Patricia Hewitt and Tim Yeo and local Pas de Calais heavyweight Philippe Vasseur, alongside the likes of arms industry fixer Lord Levene (chair of General Dynamics UK, and former National Armaments Advisor), and the infrastructure boss of Goldman Sachs.

- Nearly 3/4 of the company’s income comes from its 90+ year tunnel concession. Almost half of revenue is from the “Shuttle” train transporting cars and trucks, another quarter from access fees paid by Eurostar and freight train operators. These revenues are regarded as highly stable: so long as trade flows freely across the channel, Eurotunnel is on to a sure thing. The biggest cloud on the horizon is the great unknown of Brexit.

- Eurotunnel is now highly profitable, after a difficult start when it was held down by massive debts from the tunnel construction. Debt restructuring in 2007 reversed the company’s fortunes — at the expense of thousands of small shareholders who saw their holdings slashed in value. The company is now the property of international investment funds, first amongst them Goldman Sachs with 15% ownership, who extract big dividends and pay minimal tax.

- Eurotunnel still has outstanding debts of around €4 billion, and is currently looking to refinance these at lower interest rates.

- The man who pushed through the 2007 Goldman Sachs deal was Jacques Gounon, who has been at the helm since then unchallenged as both chairman and chief executive.

- Eurotunnel had a record year in 2015, despite terror scares and the “migration crisis”. This hasn’t stopped it announcing plans to make a €29 million claim on the governments for “revenue losses due to migrant pressure”. Back in 2009 it won a €24 settlement from the two states in a secretive ISDS court ruling about earlier costs related to border security in 1999-2002. This is on top of the undisclosed millions transferred every year by the governments for border security outsourced to Eurotunnel.

- Although the company’s income from the tunnel is stable, it offers limited growth. So Eurotunnel is seeking to expand into new business areas, including expanding its own rail freight business. Other new schemes include a golf course and “eco-village” development near the French tunnel terminal at Sangatte; the Eleclink electricity grid interconnector; and participating in a failed bid for London City Airport.

- With a long term concession on key trans-national infrastructure, backed by two governments and one of the world’s most powerful investment banks, with powerful friends on the board and even a state-subsidised private army, Eurotunnel’s future seems assured. But nothing is for sure, and the last section of the report profiles some challenges for the company’s future.

- Will Brexit lead to a trade downturn? Will security problems return on the tracks and roads that lead to the tunnel? Will workers stay quiet if there are new “restructurings”? Will dependence on specialist suppliers be an issue? Can Eurotunnel keep local authorities sweet as it continues to expand its terminals and facilities? How will it fare as it moves into new riskier ventures?

The Tunnel

The channel tunnel opened in 1994. It runs for 50 km between Coquelles and Folkestone. There are in fact three linked tunnels: two for rail traffic in either direction, and one central service tunnel. There are two crossover points in each side where trains can switch between the tunnels, so flow can continue even if a part of a tunnel goes down for maintenance. Traffic flows 24 hours a day, managed by two control centres at Coquelles and Folkestone. The tunnel carries 4 main types of traffic, all by rail:

Business overview

Eurotunnel emerged out of the original consortium that built the tunnel, and has the concession to maintain and run the tunnel until 2086.

Around half of all its income (47%) comes from the “Shuttle” service, a special train that carries both freight lorries and passenger vehicles (cars and coaches). Another quarter (26%) comes from access fees paid by other train operators for using the tunnel, both freight trains and the Eurostar passenger train.

In recent years, Eurotunnel has sought to diversify its business model beyond the tunnel. Another 25% of its revenue now comes from the Europorte rail freight subsidiary, which operates freight trains in the UK and other parts of France. A small amount (2%) comes from other sidelines including a rail training centre and property development. A major new project is the Eleclink electricity interconnector now being run through the tunnel. Eurotunnel continues to look for new ventures, for example last year it was part of a consortium that (unsuccessfully) bid to take over London City Airport.

The parent company is called Groupe Eurotunnel SE (GET), based in France and registered under French law. There are 4000 employees altogether.

- Tunnel Concession

Eurotunnel is responsible for all maintenance and operation of the tunnel. This side of the business gets income in two main ways: running its own Shuttle services (freight and passenger); and charging access fees to other train operators. In 2015 tunnel income made up nearly three quarters of all Eurotunnel’s revenue. 47% came from the Shuttle; 26% from access fees.

Truck shuttles. Currently there are 15 shuttle trains each carrying either 31 or 32 trucks, with 6 departures per hour at peak. Three new shuttles were in the works for 2016, aiming to increase peak departures to 8 per hour. Drivers travel in a separate club car. Just under 1.5 million trucks were carried in 2015, an estimated 37% of all freight traffic in the “short straits” routes (i.e., Dover to Calais and nearby ports).

Passenger shuttles. These carried over 2.5 million cars and 58,000 coaches in 2015, estimated at 52.6% and 37.7% respectively of short straits markets. Despite terrorist and migration scares, car traffic was only down 0.6% on 2014, and market share was up as the market overall declined by 2.7%.

Eurostar. 10.4 million passengers in 2015 (7.3 million passengers London-Paris route and 3.1 million London-Brussels route). This is around 79% of total rail and air passengers on these routes. NB Eurotunnel and no doubt Eurostar sees its main competition here as air travel, not coaches which serve a largely different demographic. In 2013 DeutscheBahn obtained an agreement to run a rival passenger service through the tunnel. This was initially expected to start in 2016, but in January 2016 it announced that the service would not be ready this year.

Rail freight services. The main companies running freight through the tunnel are DB Schenker, SNCF, and Eurotunnel’s own Europorte and GB Railfreight.

NB: technically there are still two concessionaires, France Manche SA (FM) and The Channel Tunnel Group Limited (CTG). This dates back to the original structure of the Anglo-French joint venture. In practice both are controlled by Groupe Eurotunnel and operate as one business.

Business and credit analysts consider tunnel income to be reliable and stable. For example, Fitch Ratings describes Eurostar demand as “highly stable”, and says about the Shuttle business:

“The Fixed Link is a rail project; nonetheless, the bulk of the revenues come from truck and cars using the shuttle, so that the economics of the project are largely similar to a road tunnel … is considered stronger than a typical stand-alone road stretch, mainly in light of the critical nature of the infrastructure asset which enables the Fixed Link business to benefit from a much wider catchment area (substantially the whole of UK and its trade relations with continental Europe) than would normally be for a single-asset project.” www.fitchratings.com/site/pr/989318

The obvious competitors are the “short straits” ferry operators, P&O and DFDS Seaways, as well as airlines in the passenger market. Eurotunnel’s service is faster, generally more reliable, and less dependent on issues such as fuel costs or bad weather. Also, its business got a boost when the third ferry operator, Sealink, shut down in 2012.

So far freight and passenger volumes across the channel have appeared very stable, with little major impact since the financial crisis. Terror and migration scares in 2015 did not even dent Eurotunnel’s revenues, and in fact it seemed to have gained business from competitors who were harder hit by these. The obvious risk factor at the moment is the impact of Brexit on UK-France trade, currently the big unknown.

But while tunnel revenues are stable, they offer limited room for growth. If Eurotunnel hikes prices too much, its ferry rivals will take up business. And there are hard limits on how much it can increase size and frequency of trains through the tunnel. The three new freight shuttles due in 2016 planned to take peak departures to 8 per hour; but there are technical and safety issues as traffic increases. Another constraint on tunnel traffic is in fact border security: increasing checks on vehicles and trains also means slowing down traffic.

- Europorte rail freight company

This subsidiary is responsible for all Eurotunnel’s own freight train operations beyond the Shuttle. These bring in the other 25% of revenue. Europorte itself has a number of further subsidiary companies.

The UK subsidiary is GB Railfreight. This is the UK’s third largest rail freight operator. The UK rail freight market is valued at about £900 million, with GB Railfreight having a current market share of approximately 17%. Eurotunnel is optimistic that this market is set to grow. Although one risk factor relates to decline in the coal transporting sector: this is a major part of GBRFs business, and is being hit by moves away from coal generation in the UK.

See here for much more information: www.gbrailfreight.com/services

In France, subsidiaries are: Europorte France (EPF: general railfreight in France, averaged around 250 trains per week in 2015, with a fleet of approximately 70 main line electric and diesel locomotives interoperable with neighbouring European countries); Socorail (logistics services on industrial sites and ports); Europorte Proximite (EPP) (maintenance of low-power diesel locomotives used by Europorte France and Socorail); Bourgogne Fret Service (grain transport freight forwarder, a joint venture with its customer Cerevia, union of agricultural cooperatives); Europorte TCSO (operates freight terminal in Bordeaux).

In contrast to the UK, French rail freight has been in a long term decline, virtually halving since 2000, although there has been some recovery since the low of 2010. Europorte has under 5% of the market: it transported 1.2 billion tonne-kilometres, out of a total 25.62 billion tonne-kilometres.

Smaller and developing operation segments:

- Land and property development

Eurotunnel has land and property development projects near its terminals on both sides of the channel.

In Kent, Samphire Hoe is a 30 hectare area of reclaimed land at the foot of Shakespeare Cliff, built on “spoil” (excavated earth and rock) from the tunnel construction. It is now run as a nature reserve together with “White Cliffs Countryside Partnership”. www.samphirehoe.com/uk/home

In Sangatte, on the French side, Eurotunnel is developing an “integrated seaside eco-village and golf course project” at the Porte des Deux-Caps. The site includes the location of the former factory where the tunnel lining segments were made, which later became the Red Cross run Sangatte refugee camp. The development will be carried out by Eurotunnel subsidiary Euro-Immo GET under a concession agreement with the regional authority (Conseil Regional). According to Eurotunnel’s website:

“The concession agreement was signed on 18 February 2013. In general terms, the development of the area entrusted to Euro-Immo GET, the project supervisor, encompasses all the work relating to roads, networks, open spaces and various facilities designed to meet the needs of the future occupiers, owners, inhabitants and users of the new buildings. The concessionaire will manage the assets acquired until they are transferred to the builders. The concession will last for 10 years.”

See much more here: www.eurotunnelgroup.com/uk/eurotunnel-group/Euro-Immo-GET/Index

- CIFFCO: railway training centre

Full name: the Opal Coast International Railway Training Centre. This is a railway staff training centre, 100% owned by Eurotunnel, but also marketed at other train operators.

- Eleclink: building an electrical interconnector

This is an electricity interconnector project — i.e., a big cable that connects the national grids of UK and France, and will run through the tunnel. The interconnector is not operational yet, work will begin in 2017 and it should be live by 2020. The size is 1GW, half the size of the largest existing interconnector (2GW), which is an undersea cable. The UK National Grid as a whole usually draws about 60GW. The project is valued at Eu500m+; current capital is Eu147m, and additional funds will be raised by auctioning capacity in advance. www.eurotunnelgroup.com/uploadedFiles/assets-uk/Media/Press-Releases/2016-Press-Release/160823-GET-Control-ElecLink.pdf

- Bidding for London City Airport

In November 2015 the Financial Times reported that Eurotunnel was planning a “spate of deals” including joining one of the consortiums bidding to buy London City Airport. However, the bid was won by another consortium including Canadian funds and the Kuwait Investment Authority.

www.ft.com/content/048bd1e6-82f8-11e5-8e80-1574112844fd

www.ibtimes.co.uk/london-city-airport-bought-by-kuwait-investment-authority-ontario-teachers-pension-plan-3-others-1546106

History of Eurotunnel

Beginnings

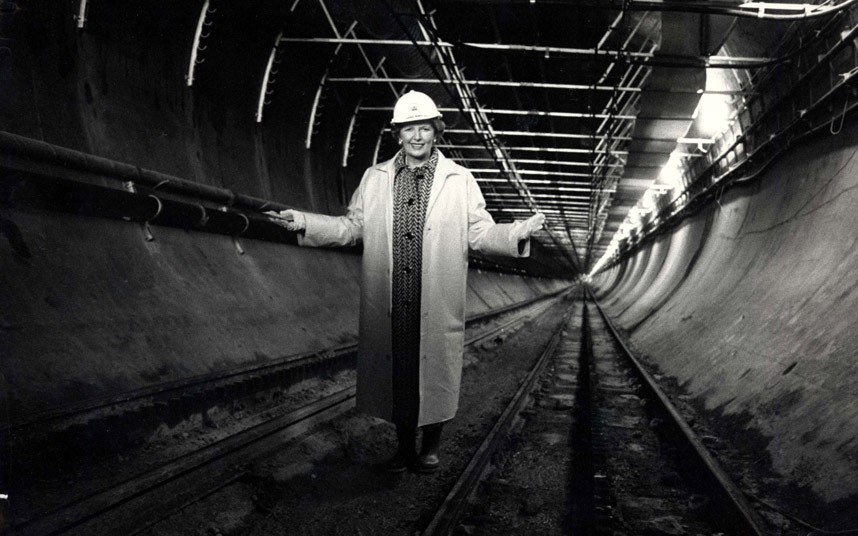

In 1984, the French and British governments agreed to tender for private contractors to build and operate a cross-channel “fixed link” scheme, and adverts went out in April 1985. The Thatcher government famously insisted that the scheme must go ahead without a penny of public money, and the tunnel has been described as “an experimental arrangement seen by free-market politicians as a crucial acid test of whether private finance could be successfully used for major infrastructure projects.” (The Channel Tunnel Story, Graham Anderson and Ben Roskrow, xii). A Franco-British consortium originally called France-Manche-Channel Tunnel Group won the bid in 1986, and launched the Eurotunnel company. The final inter-state agreement called the Treaty of Canterbury was signed in July 1987, and the first boring work began on the UK side in December 1987. The tunnel opened for business in June 1994.

Essential Eurotunnel brochure with key facts

Key founding documents and reports on tunnel infrastructure

The original consortium was made up of major building companies and banks from both sides. It is maybe worth noting that three of the building companies, one from the British side and two from the French side, have since become part of Vinci. The consortium members were:

- UK side: Balfour Beatty Construction; Costain; Tarmac Construction (now Carillion); Taylor Woodrow Construction (now owned by Vinci); Wimpey International Construction (now owned by Carillion); National Westminster Bank (now Royal Bank of Scotland); Midland Bank (now HSBC)

- French side: Bouygues S.A; Dumez S.A (now Vinci S.A.); Société Auxiliaire d’Entreprise S.A. (SAE) (now Eiffage S.A.); Société Générale d’Entreprises S.A. (SGE) (now Vinci S.A.); Spie Batignolles S.A.; Crédit Lyonnais; Banque Nationale de Paris (now BNP Paribas); Banque Indosuez (now Calyon)

The company then listed on French and UK stock markets. In its Initial Public Offering (IPO), around 50% of shares in the UK were sold to small private investors, partly encouraged by cheap fare perks. In the early years, a very high proportion of both French and British shareholders were “retail investors”. The company also raised funding through debt agreements with a group of around 200 banks.

Near bankruptcy and 2007 Restructuring

The construction of the tunnel massively overspent, incurring large debts. For its first 15 years, Eurotunnel lost money: traffic numbers were half the optimistic projections, and revenues from the tunnel were never enough to meet debt repayments from the construction.

In 2004, there was a “shareholder rebellion” which led to a couple of years of infighting amongst investors and board members. The eventual outright winner was Jacques Gounon, who joined the board in December 2004, then became chairman in February 2005, and has been both Chairman and Chief Executive since 2007. www.nytimes.com/2005/06/11/business/worldbusiness/chief-of-eurotunnel-quits-amid-turmoil-on-board.html

In 2005 the company was placed under French bankruptcy protection, i.e. debts were frozen and it was put under supervision of the Paris Commercial Court while the management attempted to restructure the debt. Gounon worked up a proposal with two main financial backers: Goldman Sachs, and the Australian investment bank Macquarie. This proposed that creditors accept a significant write-off in debt with some debt exchanged for shares, thus also diluting the holdings of existing shareholders. There was opposition both from shareholders — the thousands of small “retail investors”, who lost heavily on their shares — and a group of creditors led by Deutsche Bank, but the Gounon-Goldman Sachs deal won out. Deutsche Bank managed to get a piece of the action of the new restructuring loan deal.

The management and shareholder backers concluded negotiations with shareholders and lenders in 2007, and the restructuring was approved. Essentially, the two UK and French listed companies (Eurotunnel PLC and Eurotunnel SA) were wound up and replaced by a new company called Groupe Eurotunnel, administered under French law and listed on the Euronext Parisstock exchange (NB it is now also listed on NYSE Euronext London). The total debt was reduced from £6bn to £2.84bn. A consortium of international banks including Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank took on this remaining debt in the form of long term loans.

Eurostar is now owned by major international financial institutions, largely based in the US. In 2009, Goldman Sachs converted a large amount of its debt holding into shares, to become the major owner with now over 15% of shares.

The restructuring also involved “streamlining” management and cutting about one third of the work force.

BBC article on the restructuring

FT interview with Gounon 2015.

Detailed documentation of the restructuring

Report by Attac France

There is also a detailed study in Chapter 13 of Creating Value through Corporate Restructuring, Stuart Gilson, Wiley & Sons, 2010

Recent developments

In September 2008, a major fire hit one of the rail tunnels, which was then shut down for several months, hitting Eurotunnel’s revenue.

In 2011, Eurotunnel made a full year profit for the first time. Since then it has been profitable every year. In recent years, Eurotunnel has sought to expand into new projects and business lines, some more successful than others, such as the MyFerryLink venture.

- MyFerryLinkUpon the liquidation of Sea France, a ferry company operating between 1996-2012, Eurotunnel purchased three of their vessels. The ferries were rebranded as MyFerryLink and leased to the SCOP, a society of the ferry workers. However, the UK Competition Commission ruled that the ferries gave Eurotunnel too high a share of the cross-channel market, and in 2015 it was forced to sell them to DFDS. In July 2015, there were major strikes by MyFerryLink workers who feared job losses as a result of the sale, which involved occupation of one ferry and blockades that caused major disruption and blockage on both sides of the channel. This strike was then commented on massively in the media, with trade organizations claiming to be losing huge amounts of money each day as a result of disruptions.

- Migration “crisis”In August 2015, the blockages caused by the MyFerryLink dispute, combined with the growing numbers of migrants stuck at the channel, led to an escalation of people targeting the tunnel and trains in large groups as a way to cross to the UK. This also led to a growing number of deaths on the tracks. More of concern to Eurotunnel were the delays caused. As the media again whipped up a storm around images of the migrant “hordes”, Eurotunnel pressed the UK and French governments to step up security. They got their wish, with miles of new razorwire-topped fences, desertification and flooding of the area around the tunnel, doubling of security guards plus a massive police presence.

But despite the migrant “crisis” and also Daesh terror attacks in France, Eurotunnel’s revenues and profits continue to go from strength to strength. Following a highly profitable year in 2015, results were even better in the first half of 2016, with boss Jacques Gounon commenting: “Month after month Eurotunnel has broken traffic records, particularly for the Truck Shuttles. The Tunnel has never been as highly utilised as it is today.” Half year revenue was up 2% and EBITDA up 4%. www.eurotunnelgroup.com/uploadedFiles/assets-uk/Media/Press-Releases/2016-Press-Release/160710-2016-half-year-results-Eurotunnel-Group-web.pdf

Eurotunnel and border security

From the start, Eurotunnel and the militarised border at Calais have been inextricably linked. It was in the initial negotiations between the two governments about the tunnel that the system of “juxtaposed controls”, in which UK border control moves to French soil (and vice versa), was first worked out. The original tunnel concession agreement already explicitly referred to the system, and specified that: “15.2 The two Principals will arrange frontier controls in a way which reconciles so far as possible the rapid flow of traffic with the efficiency of the controls.” The 1987 Treaty of Canterbury set out the principle that the concessionaire (Eurotunnel) would be responsible for building and maintaining border control infrastructure; however its costs would be reimbursed by the governments: “Each Government shall be responsible for the payment or recovery of the costs of its own controls.” The details were worked out in the Sangatte Protocol of 1991, which became UK law through the “Channel Tunnel (International Arrangements) order 1993”. So the system was all in place before the tunnel actually opened in 1994.

Concession agreement

Treaty of Canterbury

Channel Tunnel (International Arrangements) Order 1993

In 2007, Eurotunnel won a case in the Hague Court of International Arbitration against the two governments, ordering them to pay €24 million for costs incurred due to lack of adequate border security around the tunnel in 1999-2002. The court ruled that the states had failed to live up to their obligations under the Treaty of Canterbury. This was only the second judgement against the UK under the Investor State Dispute Settlements (ISDS) procedure, which allows corporations to sue governments in secretive closed tribunals. The full details of the ruling have not been disclosed, and the amount was revealed only years later in 2015 after an FOI request by War on Want. www.waronwant.org/media/uk-and-france-paid-24m-euros-calais-migrants-isds-case; news.vice.com/article/eurotunnel-wants-france-and-britain-to-pay-105-million-to-cope-with-migrant-crisis-in-calais.

It is not clear just how much the company has spent on security against migrants in the years since, or how much of the bill has been met by the two governments. Eurotunnel’s 2015 Registration Document (p135) gives a total figure for tunnel security expenditure of €29 million in 2015, much higher than €12 million in 2014 and €11.3 million in 2013.

In October 2015 immigration minister James Brokenshire stated that “HM Government has invested over £20 million to reinforce border security through infrastructure improvements at the juxtaposed ports. This has included £7 million for fencing at Coquelles and we are further supporting Eurotunnel with key physical security costs related to the migrant pressures there. This includes funding 100 Eurotunnel security guards and essential security infrastructure work.” www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-question/Commons/2015-10-15/12090.

Eurotunnel itself says (2015 Registration Document p33) that it responded to the “unprecedented migration crisis” with a “three-point safety and security plan:

• High security fencing: 40 km of fencing, including ground reinforcement for 10 km of existing fencing;

• Clearing following the request from the Authorities: clearance and thinning of hedges and bushes over 56 hectares around the

Concession site;

• Security staff: staff numbers substantially increased.”

Eurotunnel says that this time “the governments of France and the United Kingdom responded immediately with operational solutions to secure the Fixed Link terminal in Coquelles.” And that “the joint contribution by the British and the French governments (financing of the reinforced security around the Tunnel by the former and massive deployment of mobile gendarme units around the clock by the latter) helped improve the situation. The mobile gendarme units virtually stopped intrusions on the site, using anticipatory manoeuvres in the areas leading up to the site, where they intercepted migrants before they could enter the Concession area. This provided the optimum security conditions to finalise the installation of the new high security fencing. The Fixed Link now has a high level of protection, following the major investment programme and the support of both France and the United Kingdom who are in charge of border controls. In the long term, it is intended to continue to reinforce the security measures.”

However, in other statements Eurotunnel was not so positive about the governments’ security efforts. In a February 2016 article in The Guardian, Gounon said: “I regret that when I asked for reaction in the first half (of 2015) I could not persuade the state that action was needed.” www.theguardian.com/business/2016/feb/18/eurotunnel-claims-compensation-for-migrant-disruption

And indeed in the company’s February statement announcing its 2015 annual results, it says that it is making a claim against the governments (to the Intergovernmental Commission which regulates the tunnel) for lost revenue amounting to €29 million. In its own words: “The security of the Fixed Link being the responsibility of the two governments, a claim for €29 million has been made via the Intergovernmental Commission, to compensate essentially the revenue losses due to migrant pressure. No revenue relating to this claim has been accounted for in 2015.”

We haven’t seen further news recently about that claim: whether the governments paid up, Eurotunnel dropped it, or whether maybe another ISDS court case is on the cards. We can make a couple of final points:

- The Treaty of Canterbury specifies that border control, and so related security, costs should be reimbursed by the governments. But this claim is not about security costs, which the governments did pay, it is about lost earnings. The 2015 Registration Document says that the “net impact on operating costs for the 2015 financial year is Eu7 million” from the “migration crisis”. The claim for lost earnings is much higher than this.

- Eurotunnel’s earnings in 2015 were actually its best ever. Revenues “reached €1.222 billion, an increase of €54 million (+5%) compared to 2014”, according to the same results statement. And it made a record profit of €100 million, €26 million higher than the year before. If its claim on the governments were met, its revenues (and presumably, profits, as all costs are already accounted for) would be €29 million higher still. I.e., the “migration crisis” didn’t stop the company (and Goldman Sachs and its other shareholders, who pocketed €97 million of that profit straight away as dividends) from having a record year.

Eurotunnel vs. migrants

For Eurotunnel, migrants are not human beings, just a problem of security and lost revenue. In its official publications, Eurotunnel routinely uses dehumanising and demeaning language to talk about Calais refugees. In the 2015 Registration Document, they are described as “illegal immigrants”. Habitually, the company refers to them in French as “clandestins”: clandestines, illegals.

Through the 2015 “crisis”, over a dozen people were killed at the tunnel: electrocuted, run over by trains. More were injured by falls, razorwire fences, or beatings from police and security guards. We are not aware of one sympathetic comment expressed by Eurotunnel towards the dead or their families. Instead, after each death the eurotunnel twitter feed apologised to its customers for the inconvenience caused by unspecified delays.

To give one example, here was the message put out by @eurotunnel at 12.08am on 16 October 2015: “Our Passenger service is currently disrupted due to an earlier incident in the process of being resolved. Please accept our apologies ^CM”. twitter.com/LeShuttle/status/654916815391428608

The incident in question was in fact the death of a 16 year old Afghan boy, who was run over by a freight train, his body “torn to shreds over more than 400 metres” according to emergency services.

The statements by boss Jacques Gounon are even more clear. In July 2015, after the death of Saleh, a 23 year old refugee man from Sudan, Gounon told the press:

“We are not talking about a passenger who didn’t pay his ticket, we are facing systematic massive invasions, perhaps even organised with the aim of getting media attention because, in the end, no one succeeded in crossing the channel tunnel”. www.francetvinfo.fr/economie/le-pdg-d-eurotunnel-denonce-des-invasions-massives-peut-etre-meme-organisees_1702009.html

In October 2015, after another Sudanese man named Abdul Rahman Haroun did succeed in walking through the access tunnel, only to be arrested and imprisoned on remand in the UK, Gounon gloated: “just one illegal has finished his journey, in Folkestone, where he will be imprisoned for 2 years”. He continued:

“Let’s be clear: the other night, these were very far from poor unfortunates who seek refuge in England and have a right to a humanitarian approach. We were faced by veritable commandos, well coordinated, who haven’t just come up against us: they also massively attacked the port and stoned the trucks on the road to the port. Their goal: to make politics and destabilise the government.”

Despite Gounon’s assertion, Abudul Haroun was in fact not imprisoned for two years, but acquitted. Many others have been less fortunate. These are just a few people we know about who died at or near the tunnel in 2015:

31st May/1st June: a man from Eritrea was killed on the A16 Highway at the entrance to the Eurotunnel.

26th June: Getenet, a 32 year old man from Ethiopia was killed attempting to board a shuttle service in the Eurotunnel.

7th July: Abdel, a 45 year old from Sudan was found in the entrance to the Channel Tunnel during an inspection of a train, having suffered head injuries while trying to board a shuttle service

13-14th July: A Sudanese man died trying to go to England by the Channel Tunnel.

16th July: Mohamad, a young Pakistani man of 23 years has died of his injuries from an accident in the Channel Tunnel on the night of July 13 to 14.

19th July: Houmed, an Eritrean teenager of 17, drowned on the site of Eurotunnel.

23rd July: A teenager was found dead in the English part of the Eurotunnel at Folkestone.

24th July: Ganet, a young Eritrean woman hit by a car about 5:30 on the A16. People at the scene reported that she was gassed in the face by the police before she was hit

28th July: Sadik, 30 years old, from Pakistan, died following an accident in the tunnel on the morning of July 27.

28th-29th July: Saleh, a 23 year old Sudanese migrant was found dead in the Channel tunnel

17-18th September: Eyas, 23 years old from Syria, was electrocuted on top of a train in the Eurotunnel. One or two others were hospitalized

24th September: Adam, from Sudan, was hit by a train in the Eurotunnel.

30th September: Berihu, a 23 year old man from Eritrea, run over by a train.

15th October: a 30 year old Syrian woman was run over and killed on the A16 highway, on the approach to the eurotunnel.

16th October: a 16 year old from Afghanistan run over by a train.

For more information see calaismigrantsolidarity.wordpress.com/deaths-at-the-calais-border

Greenwashing

The Channel Tunnel project in itself caused enormous environmental damage. To improve its environmental image, Eurotunnel has promoted various “greenwashing” initiatives such as turning the reclaimed land on the English side produced by tunnel boring waste into the Samphire Hoe nature reserve.

Currently, Eurotunnel working with the Conseil Regional and the local municipality is developing a tourist “eco-village” at Sangatte. Despite its “eco” claims, one of the main selling points of this development is a golf course.

In 2015, as part of the increased security measures, Eurotunnel re-landscaped the land around the French tunnel entrance, cutting down all trees and other life nearby then flooding the land.

Investors

Lenders

In 2007 all Eurotunnel’s outstanding debts were restructured as long term loans bought by a consortium led by Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank. These loans were then securitised with the issuance of bonds by a special purpose vehicle called Channel Link Enterprises Finance (CLEF). (See below for details). There is no publicly available information on who currently holds those bonds.

Shareholders

Goldman Sachs (specifically, the GS Infrastructure Partners division) is the “key shareholder” with over 15% ownership, and the only one represented directly on the board. Its shares are held through a Luxembourg registered fund. GS has been the primary shareholder since 2009: it was instrumental in the restructuring deal of 2007, taking on much of the company’s restructured debt, then converted debt into shares in 2009.

www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2009/09/08/goldman-sachs-va-devenir-le-premier-actionnaire-d-eurotunnel_1237483_3234.html

www.boursier.com/forum/blog/blog-conseils/groupe-eurotunnel-gounon-envisage-de-refinancer-1-milliard-de-dette-i54535-9.html

www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/transport/6152567/Goldman-Sachs-fund-takes-21.2pc-stake-in-Eurotunnel.html

www.lesechos.fr/09/06/2006/lesechos.fr/200078192_jacques-gounon—il-est-possible-d-amenager-le-plan-actuel-d-eurotunnel.htm

Around 10% of the shares are still held by “individuals”; but the large majority are owned by big banks and other institutions, particularly from the US. Here are all the shareholders with at least 0.5% equity, checked as of October 2016:

- 1. “Aero 1 Global and International” 15.62% Lux (a subsidiary of Goldman Sachs Infrastructure Partners)

- 2. “Capital Group Co Inc” 11.43% US (6.26% direct holding, 5.17% via funds)

- 3. Norges Bank 10.14% UK (5.15% direct, 4.99% via funds)

- 4. Legg Mason Inc. 5.1% (via funds)

- 5. Rare Infrastructure Ltd 5% Aus (also majority owned by Legg Mason)

- 6. Franklin Resources Inc 4.99% US

- 7. M&G Investment Managemen 4.87% UK

- 8. Black Rock 3.41% (via funds) US

- 9. NORWAY (via its funds) 3.01% No

- 10. Eurotunnel self-owned 2.04%

- 11. VANGUARD GROUP 1.77 US

- 12. BPCE SA via its funds 1.72 FR

- 13. AMERIPRISE FINANCIAL INC via its funds 1.30 US

- 14. HENDERSON GROUP PLC via its funds 1.27 GB

- 15. BROOKFIELD ASSET MANAGEMENT INC via its funds 0.99 CA

- 16. FIDELITY INTERNATIONAL LIMITED via its funds 0.85 BM

- 17. UBS GROUP AG via its funds ) 0.83 Swiss

- 18. AFFILIATED MANAGERS GROUP INC via its funds 0.81 US

- 19. DEUTSCHE BANK AG via its funds 0.74 De

- 20. MACQUARIE GROUP LTD via its funds 0.68 Aus

- 21. COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA via its funds Aus

- 22. AQR CAPITAL MANAGEMENT LLC 0.60 US

- 23. RUSSELL INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT, LLC via its funds 0.59 US

- 24. JAPAN via its funds 0.53

All of these own under 0.5%: 25. TIAA BOARD OF OVERSEERS via its funds; 26. ALLIANZ SE via its funds; 27. SAS RUE LA BOETIE via its funds

28. COHEN & STEERS INC via its funds; 29. STATE STREET CORP via its funds; 30. PRINCIPAL FINANCIAL GROUP INC via its funds; 31. STICHTING PENSIOENFONDS ABP via its funds; 32. BNP PARIBAS via its funds; 33. ALLAN & GILL GRAY FOUNDATION via its funds; 34. MORGAN STANLEY via its ; 35. ARGONAUT CAPITAL PARTNERS LLP via its funds; 36. AVIVA PLC via its funds; 37. ECOFIN HOLDINGS LIMITED via its funds; 38. NORTHERN TRUST CORP via its funds; 39. DIMENSIONAL FUND ADVISORS LP via its funds; 40. SWEDBANK AB via its funds; 41. BANKINTER SA via its funds; 42. SENTRY SELECT CAPITAL CORP via its funds; 43. STATE OF MASSACHUSETTS via its funds; 44. KBC GROEP NV/ KBC GROUPE SA via its funds; 45. SYCOMORE ASSET MANAGEMENT via its funds; 46. CREDIT SUISSE GROUP AG via its funds; 47. GEODE HOLDINGS TRUST via its funds; 58. NOMURA HOLDINGS INC via its funds; 49. TORONTO–DOMINION BANK via its funds; 50. MONTANARO ASSET MANAGEMENT LIMITED via its funds; 51. QS INVESTORS (also Legg Mason?); 52. REGERINGSKANSLIET via its funds; 53. JULIUS BÄR GRUPPE AG via its funds; 54. GOLDMAN SACHS INTERNATIONAL; 55. GOLDMAN, SACHS & CO; 56. HENDERSON EUROTRUST PLC

Key people: board and executives

The boss: Jacques Gounon

Chairman and Chief Exec since 2005. 62 years old. Alumnus of the Ecole Polytechnique, the finishing school of almost all French senior civil servants in “technical” ministries, as well as many politicians and business elites. From there he pursued a career as a transport bureaucrat, working in the Industry and trade ministries, becoming chief of staff to then transport minister Anne-Marie Idrac in 1995. This was interspersed with spells in private sector management, e.g. at major French building company Eiffage, and before joining Eurotunnel he was “number two” at French train building multinational Alstom.

2016 FT interview (paywalled)

www.capital.fr/carriere-management/entreprendre/cas-entreprise/qu-auriez-vous-fait-a-la-place-de-jacques-gounon-pour-redresser-eurotunnel-1053477

His total pay package last year was €1.6 million.

Pay breakdown in detail:

fixed part: €500,000

bonus in 2015: €495,000

benefits in kind (car allowance) €8,910

fees for attending board meetings €65,650

value of shares granted €533,00

Total = €1,602,560

(2014: €1,497,625)

Goldman Sachs man: Philippe Camu

49 years old. Board member since 2010. He represents the major shareholder, GS Global Infrastructure Partners, the infrastructure investment fund of Goldman Sachs, and is the only other “non independent” director along with Gounon. He is a long time GS staffer, working with the company since 1992. He has now become global head of GSIP, formerly he was European head. He is a graduate of the HEC Paris elite business school (Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales de Paris). He is a also a director of Redexis Gas (formerly Endesa Gas), and until 2015 was a director of Asociated British Ports.

Board meeting attendance fees in 2015: €48,650.

Local NP2C political bigwig: Philippe Vasseur

Board member. Until earlier this year was President of Chamber of Commerce and Industry of the Nord de France — which runs the Port of Calais. former Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food from 1995 to 1997. Member of French Parliament for the Pas-de-Calais area several times between 1986 and 2000.

Attendance fees in 2015: €58,700.

UK arms dealer, financier and defence fixer: Lord Levene of Portsoken (Peter Levene)

Board member since 2012. This guy has some CV. He is chairman of General Dynamics UK, the UK branch of the global arms company, since 2001, and at the same time a crossbench peer (since 1997) who has for years advised the UK government on the arms industry and defence procurement. He is also Chairman of insurance broker Starr Underwriters UK (and vice-chair of its international parent company Starr Underwriters). He also sits on the board of China Construction Bank Asia and Haymarket Media Group. Other jobs in the past have included:

- A long career as an arms industry businessman together with government defence advisor, beginning as advisor to UK Minister of Defence Michael Heseltine and Chief of Defence Procurement (1985-19991), later National Armaments Advisor.

- Advisor to prime minister John Major on “efficiency and effectiveness”

- Chairman of Docklands Light Railway

- Chairman and Chief Exec of Canary Wharf (NB: these last two were other Thatcher flagship infrastructure projects)

- Chairman of Lloyds of London

- Vice Chairman Deutsche Bank

- Board member of Total, Sainsburys, … and more.

Attendance fees in 2015: €50,450

www.parliament.uk/biographies/lords/lord-levene-of-portsoken/2035

UK Labour politician for sale: Patricia Hewitt

Blairite minister of Trade and Industry (2001-5) and then Health (2005-7). Like other leading Blairites, she started out her career on the left of the party before becoming a New Labour careerist. She retired as Health Minister in 2007, and soon after accepted directorships at two major private health companies: Aliance Boots, the world’s largest chemist chain, and Cinven, the private equity firm that bought Bupa private hospitals. In 2009 she was caught out by newspaper reports on her expenses claims, and announced that she would stand down as an MP in the next general election. In 2010 she was exposed by an undercover “Channel 4 Dispatches” report claiming that she had taken money for political influence, and was suspended from the Parliamentary Labour Party. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2010_cash_for_influence_scandal

Hewitt is one of three members of the board’s “Safety and Security Committee”, which oversees its policy relating to migrant “incursions”. The other two are Gounon and Trotignon.

Attendance fees in 2015: €60,650.

UK Tory politician for sale: Tim Yeo

Yeo was a conservative MP until 2015, when he was deselected by his local party after his latest scandal. He was briefly Environment and Countryside minister in the John Major government in 2003-4, before resigning due to a sex scandal. He was in the Shadow Cabinet from 1998 to 2005, and later Chair of the House of Commons Energy and Climate Change select committee. In this capacity, he was exposed in 2013 by Sunday Times newspaper reports for “coaching” businessmen on what to say before the committee. One of these was the representative of Eurotunnel subsidiary GB Railfreight www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-22830707 Another was a solar energy executive: when Yeo sued the Sunday Times for libel in this case the judge found against him, agreeing that the newspaper report was “substantially true” and that Yeo’s evidence was “unreliable” and “untruthful”. After this scandal he was deselected as an MP by his local constituency party for the next 2015 election. He still has plenty of work as a director of various energy and other companies as well as Eurotunnel.

Attendance fees in 2015: €60,550.

Security chief: Philippe de Lagune

Chief Operating Officer, Safety and Ethics. Philippe de Lagune is 67. He joined the Eurotunnel Group as Security and Ethics Director on 9 September 2013. In January 2016 he was promoted to “adjoint director general”. He is in charge of high-level relations with the French and British public authorities in respect of security. Before joining Eurotunnel he worked for the state as a lawyer and national police officer, also taking roles in the defence and foreign ministries, before being appointed prefect of police in Corsica, and later a departmental prefect. He was then the French coordinator for security at the London Olympics in 2012. www.eurotunnelgroup.com/uploadedFiles/assets-uk/Media/Press-Releases/2016-Press-Release/160104-Groupe%20Eurotunnel-SE-appoints-Philippe-de-Lagune-as-Chief-Operating-Officer-Safety-and-Ethics.pdf

Security Director “for channel tunnel concession” frontline security: Dominique Schmitlin

In February 2016 Eurotunnel appointed a new security director for tunnel security, a former Gendarmerie lieutenant-colonel. He served in the French military for 33 years, starting his career as squad commander in the Combat Helicopter Regiment before joining the gendarmes. “For 10 years he was director of a number of French sites, gaining experience in management and the technical aspects of site protection including nuclear power plants”. From 1 February 2016, Dominique Schmitlin will be responsible for the security and First Line of Response (FLOR) departments for the Channel Tunnel in both the UK and France, including 300 security personnel operational 24/7, 365 days a year.”

Finances

Overall the company looks in pretty good shape financially, certainly compared to ten years ago. Revenue and profits are up and the company is paying more out to shareholders than ever before. The FT reckons its shares will “outperform” the market.

But it’s unclear how Brexit will affect it (eg www.bloomberg.com/gadfly/articles/2016-07-07/brexit-vote-adds-to-eurotunnel-woes), with worries especially around people from the UK using it if there’s a recession or the pound stays low. On the other hand, Gounon hopes for a return of the “booze cruise” market.

2015 results

Revenue: €1.2bn

Of that:

€580m is from ‘shuttle services’ – transporting goods or passenger vehicles through the tunnel

€320m is from the ‘railway network’ – basically the railways that Eurostar and freight trains use

€307m is from Europorte

plus €16m of ‘others’

Net profit: €100m

Dividend payout: €97m (2015 E81m)

The total ‘book’ value of the company (or equity) from the accounts is €1.7bn (i.e., the difference between what the company owns and what it owes to everyone other than its shareholders). The total ‘market’ value, or ‘capitalisation’, of the company is approximately €4.8bn (the total value of the company’s shares at the current market price – that’s higher than the value in the accounts because it’s based on what investors think they can make from the company in the future, rather than the value of what the company currently owns or owes).

Debt

In 2007 all of Eurotunnel’s outstanding debts were restructured as long term loans bought by a consortium led by Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank. These loans were then sold on to a special purpose vehicle (paper company) called Channel Link Enterprises Finance (CLEF), which refinanced them by selling securitised “notes” (bonds) to unspecified investors. I.e., Eurotunnel repays its loans with interest to CLEF, which then passes on the interest to the bond investors. In particular, the repayments are backed by revenues from the core tunnel concession business, which is the most stable part of Eurotunnel’s income.

According to the Eurotunnel website, the outstanding long term debt currently amounts to under €4 billion: €1.902 billion in euros and £1.553 billion in sterling. In 2015 Eurotunnel paid out €257M in interest payments on its debt, including payments on hedging contracts.

The securitised notes are made up of ten tranches with different features and maturities (time until final repayment) of between 16 and 34 years,

Two of the tranches are guaranteed by a “monoline” insurer called Assured Guaranty: i.e., this insurer undertakes to pay the difference to the holders of those bonds in the event that the bonds default. This allows the “wrapped” (guaranteed) notes to have a high credit rating of A2 from Moody’s.

The other bonds are rated at “investment grade” Baa2 (Moody’s) / BBB (Fitch), reflecting the rating agency’s opinions of Eurotunnel’s credit worthiness (and particularly of its core tunnel business). Being “investment grade” means that these bonds can be bought and held by major investment funds; if the rating were downgraded below BBB due to future negative events, there could be a sell-off of its bonds.

Recent reports suggest that Eurotunnel is currently looking to restructure its debts again. Its aim would be to refinance the debts taking advantage of current very low market interest rates, and also of an improved sense of its stability in recent years.

Although Eurotunnel’s debts are still relatively large for a company of its size, they are much lower than before 2007, and the rating agencies view them as a stable investment. According to a recent note re-affirming its BBB rating Fitch summarises its assessment like this:

“The affirmation is based on the robust financial and operational performance of the Fixed Link (railway) business unit (Eurotunnel, the operator) of Groupe Eurotunnel, which is reflected in CLEF’s healthy debt service coverage metrics. CLEF benefits from the critical nature of the underlying infrastructure asset (Channel Tunnel railway link), strong regulatory oversight (UK and French), the key Eurostar route and a long 36-year tail before concession maturity.”

www.fitchratings.com/site/pr/989318

Tax

Eurotunnel pays very little tax: a total of just €7m in 2016, or around 6% of pre-tax income; and just €2m the year before. And in 2013, in fact, it received a tax rebate of €75 million!

Its tax payments in the last two years are well below the official French corporate tax rate — and well below what it has demanded from the states in subsidies for alleged lost income during the “migration crisis”. The accounts suggest that this is mainly because of the losses the company made in previous years, which the company can use to offset taxes on current profits.

The accounts shows that Eurotunnel has one subsidiary in the tax haven of Guernsey. This is Gamond Insurance Company Ltd. According to a 2011 document the sole role of this subsidiary is “to provide the Eurotunnel Group with insurance against acts of terrorism”, this arrangement probably does not have massive tax benefits. www.eurotunnelgroup.com/uploadedFiles/assets-uk/Shareholders-Investors/General-Meetings/2011-AGM/AGM2011-answers-written-questions-UKweb.pdf

Challenges for the future

Cross-channel trade and Brexit

Eurotunnel’s position in the “short straits” trade appears stable. So long as trade continues to flow between France and Britain, it offers an important and reliable route. But overall flows could be hit if one or both countries experienced major economic downturn; or if the big wildcard of Brexit leads to the end of the single market and a resulting drop in trade.

Limits of tunnel traffic

To get maximum revenue from the core business, Eurotunnel needs to get maximum traffic through the tunnel. Three new freight shuttles were due to come on line in 2016, increasing departures to eight per hour. But there are hard limits on how many trains can pass through the tunnel in any space of time. New tech systems may help increase flows, but only to a point, and as traffic increases so do the risks.

There are still security issues

The tunnel itself is now highly secured with a 300 person private army and extensive security tech funded by the states. However, traffic still needs to reach the tunnel either by rail lines (Eurostar and freight trains) or by road (Shuttle passengers), and these access routes are not under Eurotunnel’s control. Eurotunnel notes this point in its 2015 Registration Document, particularly referring to incursions by migrants on the approaching SNCF rail lines:

“The railway facilities used by the High-Speed Passenger Train services and rail freight trains are outside the scope of the Eurotunnel Group’s Concession and could be subject to disruption from various sources. This could result in the stoppage or reduction of this traffic as was the case in 2015 on the SNCF Railways Calais Frethun site. Such events could have a negative impact on the Group’s revenue derived from the usage of its Railway Network.”

Border controls

One issue that could become increasingly relevant, and perhaps cause frictions between Eurotunnel and the two governments, is the impact on traffic flows of escalating border controls. There is a clear trade-off between the flow of traffic and trade, and border checks. If every car or container were checked thoroughly, movement across the channel would grind to a halt.

Eurotunnel has agreements in place with UK Border Force about processing times for checks of Shuttle passengers. However, over the years it and the French government has made various complaints about these agreements being broken and border checks holding up traffic. (There is detail on this issue, though now a bit outdated, in the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration report on Juxtaposed Controls from 2013 icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/An-Inspection-of-Juxtaposed-Controls-Final.pdf).

Although Border Force facilities have been expanded, the pressure for increased border security could be growing even faster. Pressure may also start to come in the other direction: large delays resulted when France introduced serious border checks on the UK side for a period in Summer 2016, officially in response to heightened terror alerts around the European Championship — but according to some rumours as a warning about Brexit.

Labour relations

In 2015 Eurotunnel faced some potentially serious workforce problems. There was potential for the MyFerryLink dispute to spread to tunnel workers, as at the same time the “migration crisis” placed workers under sometimes severe psychological stress. The 2015 Registration Document notes, in its euphemistic way, the strain experienced by workers witnessing the repeated deaths and injuries of migrants at the tunnel. In response to this management put in place a psychology team accessible to all tunnel staff, with group “talk sessions” held two to three times a week.

Despite these pressures, workplace relations stayed calm at the tunnel. However, as Eurotunnel writes in the 2015 Registration Document:

“The Group has already implemented restructuring and reorganisation in the past. Further measures cannot be completely ruled out in the future. Reorganisation could affect the Group’s relations with its employees, giving rise to labour disputes and specifically stoppages, strikes and other forms of disruption that could have a negative effect on the Group’s business and results.”

Given the nature of the tunnel, potentially it would only take quite small but focused industrial action to shut down traffic and cause major problems for the business.

Other cost and supply issues

Eurotunnel uses electricity as its main power source electricity is around 5% of total operating costs. Electricity prices are an important cost factor.

Eurotunnel depends on a number of subcontractors for security, cleaning, and some specialist services. It also depends on some highly specialist parts suppliers. The 2015 Registration Document notes:

“the rolling stock and some of the Fixed Link installations have been supplied in very small volumes by a very limited number of suppliers to meet highly specific operating requirements … the price or timeframe for such replacements could have an adverse impact on the Eurotunnel Group’s financial position and prospects.” Also for Europorte: “the need to lease new locomotives in coming years brings an increased risk of reliance on key suppliers.”

Reputation and local links

Eurotunnel’s operations can have significant impacts on the local environments and communities around the tunnel on both sides. E.g., expanding facilities or security near the entrances. It may often be reliant on planning permission etc. and other co-operation from local authorities, and so needs to keep them onside. E.g., developments like the Sangatte “eco-village” may be important in this context. From the 2015 Review:

“In relation to its development, the Group could face opposition from local communities or organisations to the installation or operation of certain types of equipment or the setting up of new activities. Deterioration in these conditions could result in permits and licences being refused or delayed, and have a negative impact on the Group’s business. … The Eurotunnel Group engages in broad consultation upstream of its projects, builds partnerships with civil society and ensures that its activities generate economic benefits consistent with the expectations of the communities.”

Government backing

Although some of the above factors could pose real risks to Eurotunnel’s business model, these could be offset by strong backing from the states. For example, if a local authority refused authorisation for a development, it might be overridden or put under pressure by central authorities. Despite being hailed as an exemplary Thatcherite private sector project, Eurotunnel in fact relies on considerable state support and is effectively treated as a key piece of (trans)national infrastructure. Having influential and extremely well-connected political figures on its Board, and being owned by one of the world’s most powerful investment banks with its own government connections on all sides, also can’t hurt.

On the other hand, Eurotunnel’s heavy demands for extraordinary compensation from the governments, particularly when it is making record profits, might not go down so well with less favourable politicians and bureaucrats.

Beyond the tunnel

Too sum up: absent some big shock from Brexit or some other crisis, tunnel income should stay stable, but its growth is limited. Thus Eurotunnel’s growth strategy involves developing new business lines of various kinds.

To date the major area it has sought to develop is rail freight in the UK and France. This exposes Eurotunnel to a whole variety of customers, suppliers, competitors, environmental and legal issues and other risk factors, which we have not profiled in this report.

Now Eurotunnel is looking to enter wholly new business sectors, e.g., property development, or bidding for London City Airport. These ventures bring Eurotunnel into areas where it does not have a dominant market position, may not be so experienced or assured, and may not be so able to call on backing from its political friends.