Evelop / Barceló Group: deportation planes from Spain

The Barceló Group is a leading Spanish travel and hotel company whose airline Evelop is an eager deportation profiteer. Evelop is currently the Spanish government’s main charter deportation partner, running all the country’s mass expulsion flights through a two-year contract, while carrying out deportations from several other European countries as well.

This profile has been written in response to requests from anti-deportation campaigners. We look at how:

- The Barceló Group’s airline Evelop has a €9.9m, 18-month deportation contract with the Spanish government. The contract is up for renewal and Barceló is bidding again.

- Primary beneficiaries of the contract alternate every few years between Evelop and Globalia’s Air Europa.

- Evelop also carried out deportations from the UK last year to Jamaica, Ghana and Nigeria.

- The Barceló Group is run and owned by the Barceló family. It is currently co-chaired by the Barceló cousins, Simón Barceló Tous and Simón Pedro Barceló Vadell. Former senator Simón Pedro Barceló Vadell, of the conservative Partido Popular (PP) party, takes the more public-facing role.

- The company is Spain’s second biggest hotel company, although the coronavirus pandemic appears to have significantly impacted this aspect of its work.

What’s the business?

The Barceló Group (‘Barceló Corporación Empresarial, S.A.’) is made up of the Barceló Hotel Group, Spain’s second largest hotel company, and a travel agency and tour operator division known as Ávoris. Ávoris runs two airlines: the Portuguese brand Orbest, which anti-deportation campaigners report have also carried out charter deportations, and the Spanish company, Evelop, founded in 2013.

The Barceló Group is based in Palma, Mallorca. It was founded by the Mallorca-based Barceló family in 1931 as Autocares Barceló, which specialised in the transportation of people and goods, and has been managed by the family for three generations. The Barceló Group has a stock of over 250 hotels in 22 countries and claims to employ over 33,000 people globally, though we don’t know if this figure has been affected by the coronavirus pandemic, which has caused massive job losses in the tourism industry.

The Hotel division has four brands: Royal Hideaway Luxury Hotels & Resorts; Barceló Hotels & Resorts; Occidental Hotels & Resorts; and Allegro Hotels. The company owns, manages and rents hotels worldwide, mostly in Spain, Mexico and the US. It works in the United States through its subsidiary, Crestline Hotels & Resorts, which manages third-party hotels, including for big brands like Marriott and Hilton.

Ávoris, the travel division, runs twelve tour brands, all platforms promoting package holidays.

Their airlines are small, primarily focused on taking people to sun and sand-filled holidays. In total the Barceló Group airlines have a fleet of just nine aircraft, with one on order, according to the Planespotters website. However, three of these have been acquired in the past two years and a fourth is due to be delivered. Half are leased from Irish airplane lessor Avolon. Evelop serves only a few routes, mainly between the Caribbean and the Iberian peninsula, as well as the UK.

Major changes are afoot as Ávoris is due to merge with Halcón Viajes and Travelplan, both subsidiaries of fellow Mallorcan travel giant Globalia. The combined entity will become the largest group of travel agencies in Spain, employing around 6,000 people. The Barceló Group is due to have the majority stake in the new business.

Barceló has also recently announced the merger of Evelop with its other airline Orbest, leading to a new airline called Iberojet (the name of a travel agency already operated by Ávoris).

The new airline is starting to sell scheduled flights in addition to charter operations. Evelop had already announced a reduction in its charter service, at a time when its scheduled airline competitors, such as Air Europa, have had to be bailed out to avoid pandemic-induced bankruptcy. Its first scheduled flights will be mainly to destinations in Central and South America, notably Cuba and the Domican Republic, though they are also offering flights to Tunisia, the Maldives and Mauritius.

A Royal Hideaway luxury hotel

Deportation dealers

Evelop currently holds the contract to carry out the Spanish government’s mass deportation flights, through an agreement made with the Spanish Interior Ministry in December 2019. Another company, Air Nostrum, which operates the Iberia Regional franchise, transports detainees within Spain, notably to Madrid, from where they are deported by Evelop. The total value of the contract for the two airlines is €9.9m, and lasts 18 months.

This is the latest in a long series of such contracts. Over the years, the beneficiaries have alternated between the Evelop-Air Nostrum partnership, and another partnership comprising Globalia’s Air Europa, and Swiftair (with the former taking the equivalent role to that of Evelop). So far, the Evelop partnership has been awarded the job twice, while its Air Europa rival has won the bidding three times.

However, the current deal will end in spring 2021, and a new tender for a contract of the same value has been launched. The two bidders are: Evelop-Air Nostrum; and Air Europa in partnership with Aeronova, another Globalia subsidiary. A third operator, Canary Fly, has been excluded from the bidding for failing to produce all the required documentation. So yet again, the contract will be awarded to companies either owned by the Barceló Group or Globalia.

On 10 November 2020, Evelop carried out the first charter deportations from Spain since the restrictions on travel brought about by the cCOVID-19 pandemic. On board were 22 migrants, mostly Senegalese, who had travelled by boat to the Canary Islands. Evelop and the Spanish government dumped them in Mauritania, under an agreement with the country to accept any migrants arriving on the shores of the Islands. According to El País newspaper, the number of actual Mauritanians deported to that country is a significant minority of all deportees. Anti-deportation campaigners state that since the easing up of travel restrictions, Evelop has also deported people to Georgia, Albania, Colombia and the Dominican Republic.

Evelop is not only eager to cash in on deportations in Spain. Here in the UK, Evelop carried out at least two charter deportations last year: one to Ghana and Nigeria from Stansted on 30 January 2020; and one to Jamaica from Doncaster airport on 11 February in the same year. These deportations took place during a period of mobile network outages across Harmondsworth and Colnbrook detention centres, which interfered with detainees’ ability to access legal advice to challenge their expulsion, or speak to loved ones.

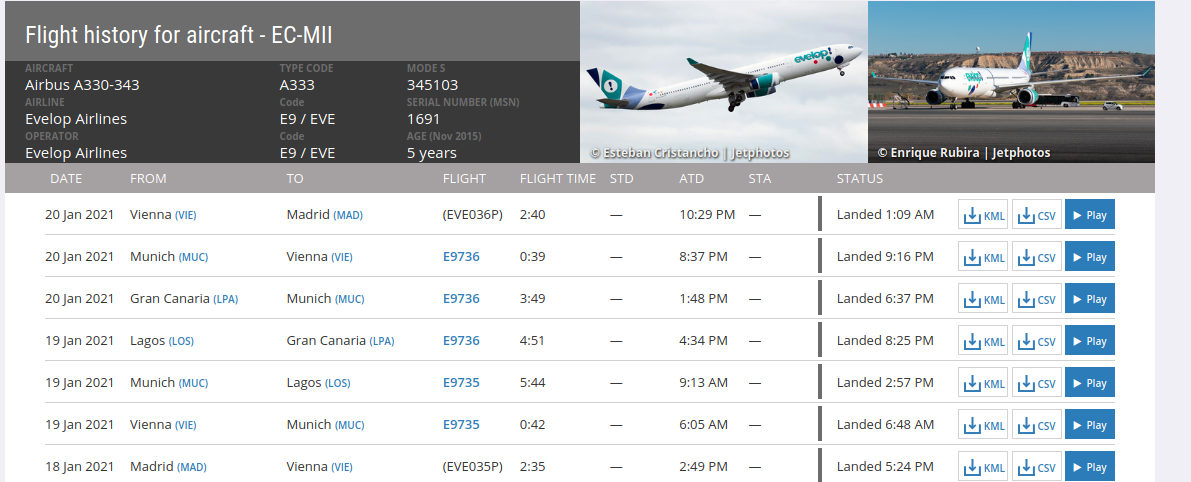

According to campaigners, the company reportedly operates most of Austria and Germany’s deportations to Nigeria and Ghana, including a recent joint flight on 19 January. It also has operated deportations from Germany to Pakistan and Bangladesh.

19 January Deportation to Nigeria from Austria and Germany

Evelop is not the only company profiting from Spain’s deportation machine. The Spanish government also regularly deports people on commercial flights operated by airlines such as Air Maroc, Air Senegal, and Iberia, as well as mass deportations by ferry to Morocco and Algeria through the companies Transmediterránea, Baleària and Algérie Ferries. Ferry deportations are currently on hold due to the pandemic, but Air Maroc reportedly still carry out regular deportations on commercial flights to Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara.

Where’s the money?

The financial outlook for the Barceló Group as a whole at the end of 2019 seemed strong, having made a net profit of €135 million.

Before the pandemic, the company president said that he had planned to prioritise its hotels division over its tour operator segment, which includes its airlines. Fast forward a couple of years and its hotels are struggling to attract custom, while one of its airlines has secured a multimillion-euro deportation contract.

Unsurprisingly, the coronavirus pandemic has had a huge impact on the Barceló Group’s operations. The company had to close nearly all of its hotels in Europe, the Middle East and Africa during the first wave of the pandemic, with revenue down 99%. In the Caribbean, the hotel group saw a 95% drop in revenue in May, April and June. They fared slightly better in the US, which saw far fewer COVID-19 restrictions, yet revenue there still declined 89%. By early October, between 20-60% of their hotels in Europe, the Middle East and the Caribbean had reopened across the regions, but with occupancy at only 20-60%.

The company has been negotiating payments with hotels and aircraft lessors in light of reduced demand. It claims that it has not however had to cut jobs, since the Spanish government’s COVID-19 temporary redundancy plans enable some workers to be furloughed and prevent employers from firing them in that time.

Despite these difficulties, the company may be saved, like other tourism multinationals, by a big bailout from the state. Barceló’s Ávoris division is set to share a €320 million bailout from the Spanish government as part of the merger with Globalia’s subsidiaries. Is not known if the Barceló Group’s hotel lines will benefit from state funds.

Key people

The eight members of the executive board are unsurprisingly, male, pale and frail; as are all ten members of the Ávoris management team.

The company is co-chaired by cousins with confusingly similar names: Simón Barceló Tous and Simón Pedro Barceló Vadell. We’ll call them Barceló Tous and Pedro Barceló from here. The family are from Felanitx, Mallorca.

Barceló Tous is the much more low-key of the two, and there is little public information about him. Largely based in the Dominican Republic, he takes care of the Central & Latin American segment of the business.

His cousin, Pedro Barceló, runs the European and North American division. Son of Group co-founder Gabriel Barceló Oliver, Pedro Barceló is a law graduate who has been described as ‘reserved’ and ‘elusive’. He is the company’s executive president. Yet despite his apparent shyness, he was once the youngest senator in Spanish history, entering the upper house at age 23 as a representative for the conservative party with links to the Francoist past, Partido Popular. For a period he was also a member of the board of directors of Globalia, Aena and First Choice Holidays.

The CEO of Evelop is Antonio Mota Sandoval, formerly the company’s technical and maintenance director. He’s very found of drones and is CEO and founder of a company called Aerosolutions. The latter describes itself as ‘Engineering, Consulting and Training Services for conventional and unmanned aviation.’ Mota appears to live in Alcalá de Henares, a town just outside Madrid. He is on Twitter and Facebook.

The Barceló Foundation

As is so often the case with large businesses engaging in unethical practises, the family set up a charitable arm, the Barceló Foundation. It manages a pot of €32 million, of which it spent €2m in 2019 on a broad range of charitable activities in Africa, South America and Mallorca. Headed by Antonio Monjo Tomás, it’s run from a prestigious building in Palma known as Casa del Marqués de Reguer-Rullán, owned by the Barceló family. The foundation also runs the Felanitx Art & Culture Center, reportedly based at the Barceló’s family home. The foundation partners with many Catholic missions and sponsors the Capella Mallorquina, a local choir. The foundation is on Twitter and Facebook.

The Barceló Group’s vulnerabilities

Like other tourism businesses, the group is struggling with the industry-wide downturn due to COVID-19 travel measures. In this context, government contracts provide a rare reliable source of steady income — and the Barcelós will be loathe to give up deportation work. In Spain, perhaps even more than elsewhere, the tourism industry and its leading dynasties has very close ties with government and politicians. Airlines are getting heavy bailouts from the Spanish state, and their bosses will want to keep up good relations.

But the deportation business could become less attractive for the group if campaigners keep up the pressure — particularly outside Spain, where reputational damage may outweigh the profits from occasional flights. Having carried out a charter deportation to Jamaica from the UK earlier in the year, the company became a target of a social media campaign in December 2020 ahead of the Jamaica 50 flight, after which they reportedly said that they were not involved. A lesser-known Spanish airline, Privilege Style, did the job instead.

For a global list of Barceló Group hotels see this page.

With thanks to @StopDeportacion, a Spanish group campaigning against Deportation Centres and Deportation flights.