Vaccine Capitalism: five ways big pharma makes so much money

The pharmaceutical industry is hugely profitable. The biggest pharma companies have profit rates of up to 20% – more than double those in other industries.i So how do pharma companies make so much money?

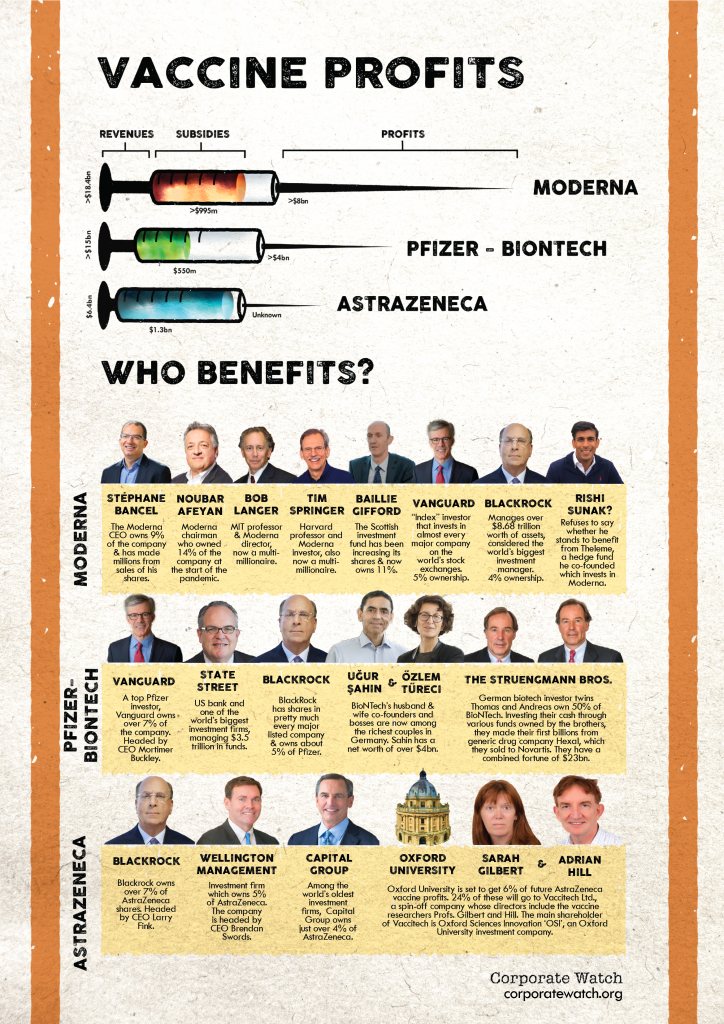

With some of them becoming household names in the UK with the mass vaccine roll-out, we have made this short guide to help people understand the industry and just how it makes money from our health (see also: our breakdown here of the profits big pharma companies are set to make from the COVID-19 vaccines).

1) Follow profit, not need

One of the biggest problems with a system that directs medical research towards profits rather than needs is that R&D funding is channelled to those products that can make pharma companies the most money. The best prospects are drugs targeted at patients who are high-value and who will use the drugs long term. Best of all are patients in the US, where prices are highest, and with chronic conditions requiring repeat prescriptions. Or, as in the case of opioids like Oxycontin, where the drugs are highly addictive. On the other hand, one-shot vaccines for epidemics that mainly affect poorer countries are the classic example of a bad business prospect. Thus vaccine research was relatively neglected until last year – when COVID-19 suddenly became a rich country issue, and state funding poured in.

2) Patent everything

Pharma companies hold patents – licenses guaranteeing their “intellectual property” rights – on new medicines. This means no one else is allowed to produce the drug without their permission for the life of the patent, which is 20 years in most countries.

The theory of free market capitalism is that if one company makes high profits, then others will come in and make the same thing but cheaper, pushing down prices and profits. But the pharma industry is no competitive market. Patents mean that pharma companies have legal monopolies on particular drugs: because no other company can undercut them, they can set high prices and make big profits.

The intellectual property system is enforced by governments worldwide under the TRIPS agreement, which is one of the key documents of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Some states are more ardent enforcers than others. The US is particularly well-known as a strong defender of companies’ intellectual property; the EU is not far behind (see this recent report by Corporate Europe Observatory).

Governments including India and South Africa, along with NGOs such as Medécins Sans Frontières, have called for vaccine patents to be waived during the COVID-19 pandemic. This could allow poorer countries to start manufacturing their own vaccines at cost price – rather than wait until 2023 for pharma corporations to meet their orders. The idea is being strongly opposed by the US, EU, UK and other rich countries.

3) Price much, much higher than costs

How do pharma industry supporters justify a system that denies affordable drugs to billions of people? The argument is that this is the only way to cover research and development (R&D) cost for new drugs. The main US industry lobby group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PHRMA) says: “On average, it takes 10-15 years and costs $2.6 billion to develop one new medicine, including the cost of the many failures.” Without patents, they say, rivals could just copy their recipes and no one would ever bother to develop new medicines.

Drug companies on average spend about 20% of all their sales revenue on R&D.ii This is indeed high compared to other industries: only the aviation and space industry is more R&D intensive. But even so, sales cover costs many times over. Once drugs are on the production line, the actual manufacturing costs are tiny compared to often sky-high prices (unlike spacecraft, which are quite expensive to produce). Which explains that 20% profit margin.

Insulin usually costs less than $6 a vial to make, but sells for as much as $275 in the US (one example given by the campaign group Patients for Affordable Drugs). In Europe, pharma giant Gilead charged an average of €55,000 for a 12 week Hepatitis C treatment – when pills cost less than €1 per pill to manufacture. Such extreme examples illustrate a general pattern. One academic study found US pharma companies have an average 71% “gross profit” margin on drug sales – the money they make from a drug after the cost of producing it, but before company-wide costs such as marketing, taxes or executive bonuses.

4) Minimise risk

The pharma companies argue they have to bear the risk of developing experimental drugs that never make it to market. For example, the average cost of a new cancer drug has been estimated at $648 billion. The $2.6 billion figure cited from PHRMA above is actually a “risk weighted” estimate which “includes the cost of many failures”. If a pharma company invents 10 drugs costing $260 million each, but only one gets approved, then it has cost $2.6 billion overall to produce one it can sell.

Except that isn’t what happens. The reality is that major pharma companies only “invent” a handful of the drugs they patent and sell. In 2019, PHRMA’s member companies only spent $13 billion on preclinical research – most of their R&D spending goes on later stage development trials, after drugs have been discovered. An analysis of two Big Pharma giants shows that Pfizer only developed 10 out of 44 best-selling drugs “in house” (23%) – and Johnson & Johnson only developed 2 out of 18 (11%). The “innovation” largely happens in university and government labs, or in those of smaller research companies.

And a lot of it is state-funded. The US National Health Institutes, the main (but not the only) government medical research body, gives $39.2 billion a year to universities, medical schools and other research organisations.

Once the drugs have been found, the pharma giants step in – to buy up a license, or a whole company – once the drug has already proved itself through initial tests. (See also: recent US report on this.) The COVID-19 vaccines are classic examples.

5) Lobby, lobby, lobby

The pharma industry is powerful, with a lot of friends in high places. In the US, the country with the world’s highest drug prices, pharma spends more than any other industry on lobbying. Over 22 years pharma companies and industry groups have spent $4.45 billion on lobbying US politicians – almost twice the amount of the next highest spending industry, insurance. According to OpenSecrets, the industry has over 1,450 lobbyists working for it, 66% of whom are former government employees. And this is just the most public, officially declared, face of pharma’s political influence – it just scratches the surface of a grubby world of political donations, board positions, “revolving doors”, and more.

A report by Corporate Europe Observatory details how the EU has become a “complacent or complicit” tool defending pharma property rights. The price tag seems to be cheaper in Brussels: the top ten pharma companies spent up to €16 million on lobbying there in 2019. In the UK, stories have emerged such as the industry funding patient groups to help lobby for new drug treatments; or NHS England commissioning research for its purchasing strategy from a lobbying group funded by the industry.

And of course, these governments are also major big pharma customers: they pay out billions of their taxpayers’ pounds to buy the companies’ drugs.

Some further reading:

Bad Pharma – Ben Goldacre. Very detailed survey of pharma industry malpractice, particularly looking at issue of who trial results are systematically fiddled.

Pharma – Gerald Posner (2020). A journalistic history of the pharma industry (mainly US) and its crimes.

US Government Accountability Office (2017) report on US pharma industry, gives a useful overview of main issues.

Patients for Affordable Drugs – US campaign group

Corporate Europe Observatory – reports on pharma industry politics in Europe

Notes

i A 2017 US government survey looked at the profit rates of the top 25 drug companies there over ten years. It found they averaged 15 to 20% over the period – as opposed to 5-9% for the top 500 companies in other industries.

ii PHRMA says its US members spend “over 20%”

Industry report Evaluate Pharma estimated 20.9% globally for 2017

In 2014-17 the biggest US listed pharma companies, members of the S&P index, spent on average 16%.