‘Self-audit’ system for detention centres revealed

[responsivevoice_button]

Home Office ‘self-audit’ system for detention centres revealed

The government’s system for monitoring companies it pays to run migrant detention centres has been called into question after a year-long freedom of information battle won disclosure of confidential ‘self-audits‘. The documents reveal how contractors are paid according to their own monthly performance reports. The Home Office has refused to say if it scrutinises the data submitted by the companies.

The Home Office was forced to hand over the files to Corporate Watch after the Information Commissioner decided there was “a very strong public interest” in doing so. The majority of Britain’s immigration detention centres are run by private companies under multi-million pound outsourcing deals. The firms are required to send monthly ‘self-audit’ reports to the Home Office, detailing any contractual failings and penalties incurred. Despite the importance of such documents in measuring compliance, it is thought to be the first time that such documents have ever been made public. The performance reports, from May 2014, reveal some failures by contractors but, more importantly, raise serious questions about the integrity of a ‘self-audit’ system.

The government’s confidence in large outsourcing companies, particularly Serco, has been challenged by a series of scandals. Serco is being investigated by the Serious Fraud Office for overcharging the government on an electronic tagging contract. In another widely publicised failing, the company recorded prisoners as being delivered to court in time for hearings when they were not.

Audits ‘should raise questions’

Contractors can provide significantly different levels of detail to the Home Office, because there is no standard template for the self-audits, it has emerged. The report lengths are arbitrary, with one contractor’s audit more than half the length than that of their rival. The GEO Group, which operated Harmondsworth, simply left blank a section titled “details of accepted failures” in their “monthly contract review tool”. The Home Office has refused to explain what follow up action it takes after receiving self-audit reports, raising concerns that the monitoring system lacks any integrity. A Home Office spokesperson commented “Self-audit reports are part of a range of measures, including regular independent inspections, to ensure our contractors continue to provide safe and secure accommodation for detainees.” (The frequency of these independent inspections is another issue – the prison inspector last visited Colnbrook in 2013, and his visit before that was in 2010.)

A Serco spokesperson told Corporate Watch: “Serco managed Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre on behalf of the Home office until August 2014. The last report before this date by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons confirmed that Colnbrook IRC was a generally well-managed centre that had been on a consistent path of improvement in recent years. The report also found that detainees had good access to appropriate primary care services.”

However, Serco’s self-audit should have caused the Home Office alarm, according to a medical healthcare professional who analysed the document for Corporate Watch. Noel Finn, a former mental health nurse for Serco, said he had “significant concerns” about the report, adding that “The Home Office has a duty of care to ask what’s going on here.” Under the contract, Serco was required to provide full medical screening to all new arrivals. However, the figures show that 686 people in one month, or 72% of arrivals, signed disclaimers to not see a doctor. The Home Office refused to comment on whether it had challenged Serco about this high number of disclaimers. When we queried this figure with Serco, the company said that “This is fairly normal. All detainees see a nurse on arrival at the centre and are asked if they want to see a doctor the next day. It was not uncommon for a large number to say that they were fine, did not want to see a doctor and sign a disclaimer. Obviously residents are able to request to see healthcare at any point while in detention.” But disclaimers enable the company to escape its contractual requirement to give a ‘full medical screening’ by a doctor, and means that almost three quarters of people in its custody (and therefore under its duty of care) were not fully checked on arrival for undiagnosed medical problems – but just seen by a nurse.

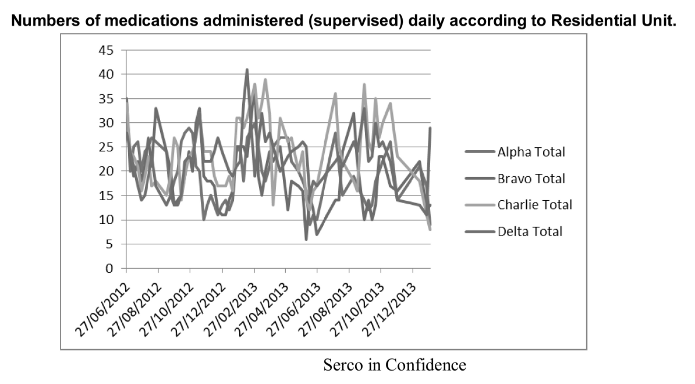

One graph in Serco’s May 2014 self-audit had months of data missing

Serco’s self-audit claims that psychiatrist appointments received 100% attendance, and that appointments with mental health nurses had 98% attendance. Serco told us that “Good attendance for mental health related clinics and meetings is not uncommon.” However, these figures are incredibly high, given that people with mental health problems are often unwilling to attend appointments. For example, a month after the report was written, a Serco mental health nurse from Colnbrook told an inquest that one detainee had become uncooperative simply when he saw the words ‘mental health’ on the nurse’s name badge. Again, the Home Office refused to tell Corporate Watch whether it had queried this attendance figure with Serco.

The report shows that only 77% of Colnbrook staff were trained in emergency first aid. This appears well below target, something that Serco effectively conceded in its response to us; “All staff would have been diaried-in to receive refresher training to provide the required level of cover for the centre”. Another point was that the nursing contingent took 17 sick days in one month, but cover was adequate “mostly due to the willingness of our staff to work additional shifts and change shifts at short notice”, Serco reported. When we challenged Serco if it was safe for healthcare staff to work extra shifts at short notice, the company said it was “not aware of any shifts that were back-to-back”, but said it no longer had access to the centre’s records. The Home Office would not tell Corporate Watch if it had raised concerns about these working practices.

Flowers, bee stings and protests

Serco’s report also contains a surprising amount of detail on mundane matters such as gardening and art classes. It is not clear why the Home Office needs to know about the daffodils in a detention centre, yet Serco’s centre director at Colnbrook reported that “The warmer weather has started to arrive and plants and flowers are now beginning to bloom adding much more colour to the garden. All the daffodil bulbs have now been removed and stored for later in the year.” And in the art room, he reported that “Lesson topics this month have been on Bracelets and how to make varied styles rather than the general straightforward ones.” The reports give a sometimes bizarre picture of what goes on inside Britain’s immigration detention centres. At Colnbrook, a member of Serco staff “wearing a full bee suit and trained as the beekeeper was stung multiple times by bees in the staff garden. She experienced an allergic reaction and swelling of the affected arm”, and required hospital treatment.

A protest inside Harmondsworth in May 2014 was ten times larger than the GEO Group, its operator, told journalists. The self-audit report for that month shows that the centre manager knew the demonstration involved “up to 300 detainees”, nearly half of all inmates. The company had told the media that “A short and entirely passive protest took place at Harmondsworth involving between 30 and 40 detainees”. GEO told Corporate Watch that it “absolutely did not consciously make a false statement to the media.” The protest was against the fast track asylum system, and detainees occupied the centre’s courtyard, sitting down and refusing food. One man involved in the protest told volunteers at the Unity Centre that “Conditions are very bad, we all feel we are going crazy. We feel alone and isolated like we have been left in the middle of the bush.” The unrest quickly spread to three other detention centres across the country. Months later, the High Court found that fast track carried “an unacceptably high risk of unfairness” and was unlawful. The system has now been suspended.

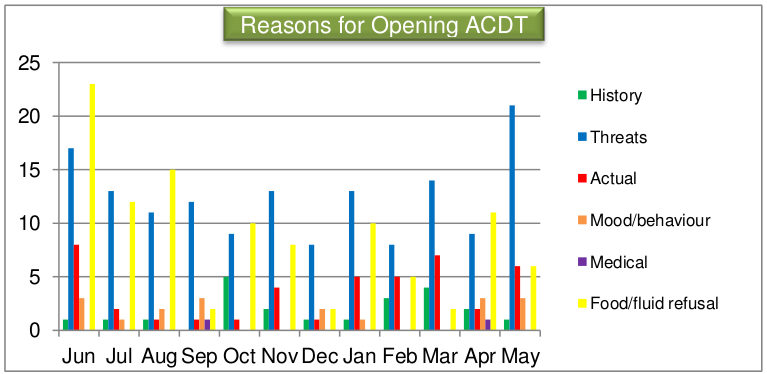

Harmondsworth: graph shows reasons why some detainees were deemed at risk of self-harm

Lawyers, TV shows and deportations

Cuts to legal aid have meant that detainees have very little access to lawyers. Serco noted that “solicitor demand continues but many [detainees] are becoming more and more frustrated due to lack of funding and options available to them.” However, the centre director hoped that tension could be reduced by sports events on TV. “There was also a lot of sport activity on the television which is always popular and diverts attention from detention. These are factors which indirectly can impact positively on the number of safety events.”

The Home Office arranges specially chartered flights for deportations to particular countries, such as Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The self-audits shed some light on how people are selected for these flights, which raises concerns that people are being rounded up on the basis of their nationality rather than their individual immigration cases.

The Harmondsworth centre manager wrote in a discussion about the number of people arriving and leaving detention that “Figures rising and falling can often be attributed to the amount of charter operations in progress by DEPMU [Detainee Estate Population Management Unit] and other pick up operations in effect from the Home office enforcement teams. In certain circumstancesthese two departments m[a]y work together to focus on a specific nationality to fill a charter which will reflect on the amount of arrivals and first night in detention and will also affect the amount of departures”. [Emphasis added]

Days after that report was written, a leaked Home Office intelligence dossier emerged which showed immigration snatch teams were targeting nationalities in specific industries, such as Nigerians working in barber shops. Rounding up people based on their nationality, in order to fill a mass deportation flight to that country, would amount to a collective expulsion, contrary to European laws.

After fighting for a year to keep these self-audits secret, the Home Office has shown that the system it uses to ‘monitor’ companies paid to run detention centres is deeply flawed. Although the companies declared a handful of failures at their centres, the Home Office does not appear to scrutinise the reports, giving the companies carte blanche to under-report issues. This leaves people in their custody vulnerable. But the arrangement could be mutually beneficial to the Home Office and its contractors – the payments keep coming, and the government can turn a blind eye.

(Mitie took over the running of Harmondsworth and Colnbrook in September 2014.)

This article was amended on 3 December 2015 following a direction from the Information Tribunal. The original version may be republished pending the outcome of a case currently being considered by the Tribunal.