Carbon Cash Machine: What if BP & Shell dividends were used for the common good?

As part of our investigation with Queen Mary University’s Centre for Climate Crime and Justice into the payouts made to BP and Shell’s shareholders since the Paris Agreement, we also looked into other ways that money could have been spent. Put simply, one billion is a thousand million, but it’s difficult to fathom what this equates to in monetary terms. And this becomes more complex still trying to conceptualise the £131bn paid out to Shell and BP shareholders since December 2015. So we wanted to reflect another perspective of what that figure might look like if it had been invested in public services or renewables.

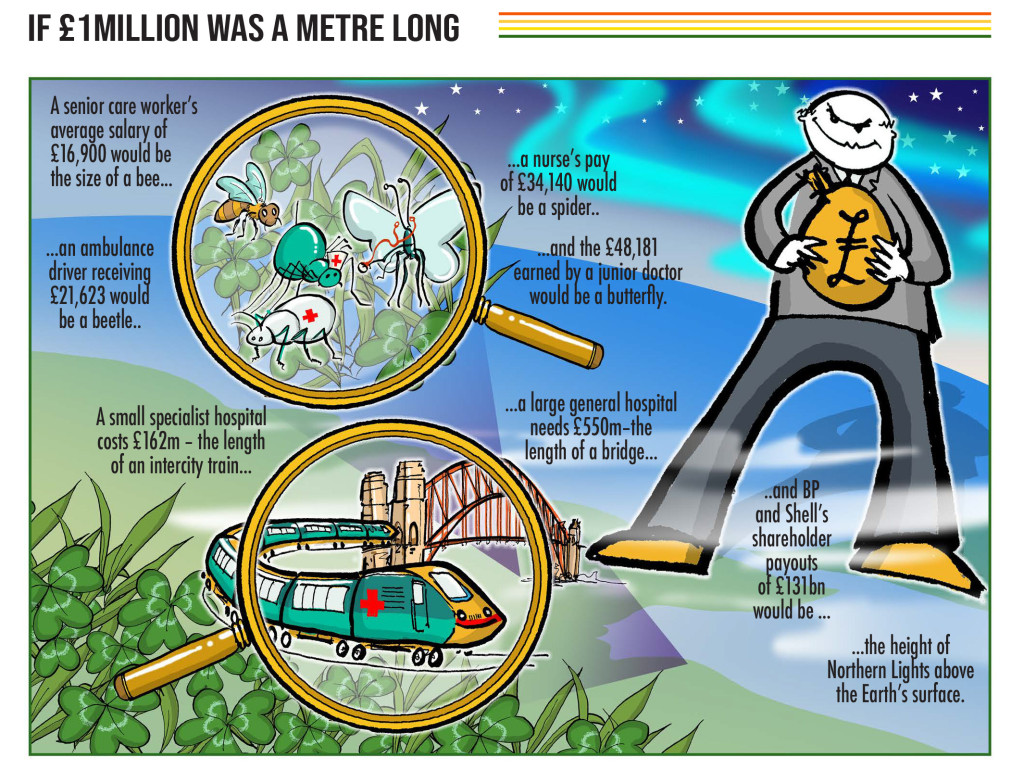

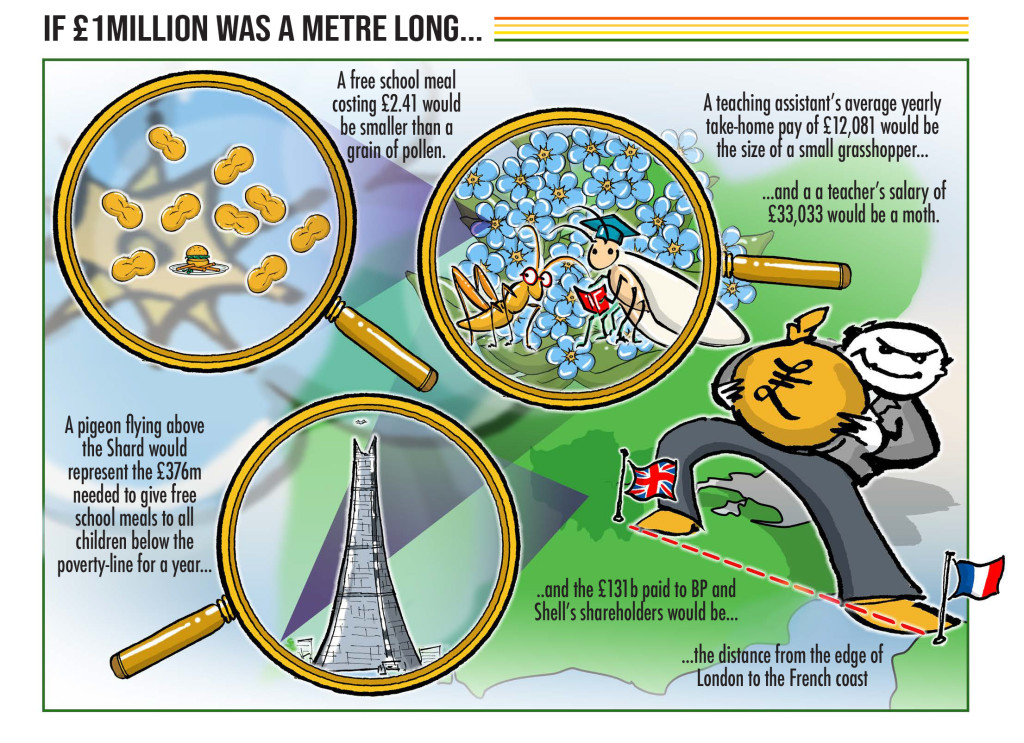

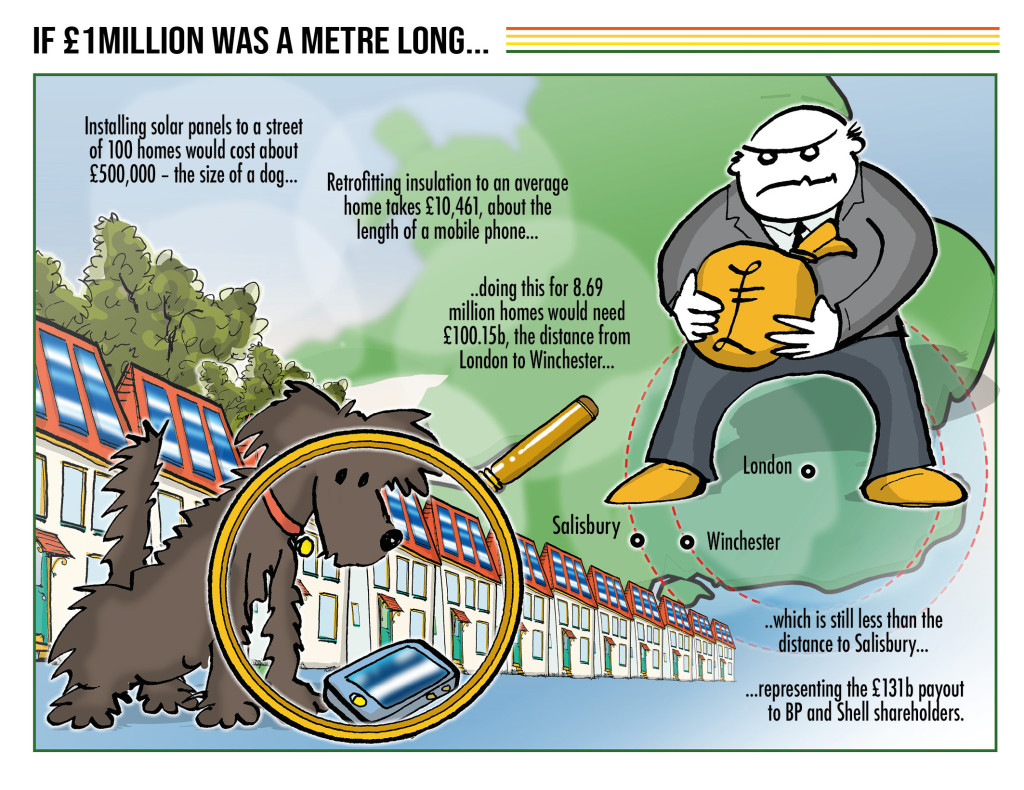

We appreciate that these figures can be hard to grasp, so the infographics below give a visual representation of the sums involved.

Healthcare

Long hours, low pay and deteriorating conditions following the pandemic are driving healthcare workers out at an unprecedented rate. Data from NHS England revealed a record 47,496 vacancies for nursing staff in 2022. In the same year, basic pay for a newly qualified nurse was around £27,000 and the average nurse’s pay (over six years) was about £34,140. Just £1.5bn could fill those vacancies with newly qualified nurses and give them a significant pay rise, while an additional £0.5bn would push wages up for all nurses and go towards actual costs of employment including pensions and other benefits. A similar pattern emerges for doctors where the starting salary (for an F1) is £29,384. Once the long hours worked are factored in, amounts to around £14.09 per hour. An additional £1bn would be enough for a meaningful pay rise (around £13,000) for the estimated 75,000 junior doctors in the UK. According to the Nuffield Trust, on any given day around 1,400 doctor posts are vacant, with more junior doctors experiencing burnout than ever before. Again, it’s little surprise that in 2022 there were 3,334 vacancies for ambulance drivers, whose average starting salary is £21,623.

This scenario is replayed in the social care sector which the Local Government Association (LGA) estimates is underfunded by roughly £13bn – one-tenth of the BP and Shell shareholder payouts. Vacant posts have soared to 165,000 – the highest on record and an increase of 52%. The government claims senior care worker pay averages £16,900, but in reality, the median hourly pay is £9.50 and almost a quarter of UK care workers are on precarious zero-hours contracts. Not only would securing better pay and conditions for care workers alleviate pressure on the NHS, it equates to just a small fraction of shareholder profits.

Whether or not the 40 new hospitals promised by Boris Johnson will be built by 2030 remains to be seen. But if the government reneges on this pledge citing costs, it’s worth noting that the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates that the average cost for one new small (specialist) hospital would be £162m increasing to around £550m for a large general hospital. So, 40 might cost somewhere between £18bn to £24bn which brings BP and Shell payouts into sharp focus.

Education

The IFS estimates that UK schools will face a £2bn budget shortfall by 2024. According to figures from the National Education Union (NEU), the starting salary for a newly qualified teacher is £28,000 and the average teacher’s pay (on main scale contracts) is £33,033. For teaching assistants, the starting salary is £18,333 (£9.50/hour) although Unison calculates that because most TAs are only paid during term time, their average salary is actually around £12,081. The incoming £2bn deficit, equates to a shortfall of around £35,000-£45,000 for most primary schools which could mean losing two support staff or one teacher. Meanwhile, secondary schools will be left £200,000-£250,000 short, equating to around four to five teachers. Nationally, this figure is equivalent to losing approximately 38,000 teachers. And these figures don’t consider the agonising choices head teachers will need to make over the “dangerous” state of many school estates and cutting extra-curricular activities or additional support for the most vulnerable pupils. As ever, schools in more deprived areas are likely to be hit hardest.

With child poverty soaring, free school meals (FSM) are a lifeline for many families. Each FSM costs the government around £2.41. So, the cost/day (in England) is about £4.5m, given there are an average of 195 days in the school year, the annual cost is approximately £877.5m. However, According to the Food Foundation, an estimated 800,000 children in England are living below the poverty line but don’t qualify for free school meals. It would cost just over £376m/year to ensure those children were fed at school. Extending provision for all pupils whose parents receive Universal Credit would cost £477m/year and going one step further to extend FSM to all children in England would cost £1.8bn/year – these figures would barely dent annual profits for BlackRock, Vanguard and co. And, as the Food Foundation point out, these models generate huge financial benefits to the wider economy.

Renewables

Renewables

Despite the ongoing greenwashing and ESG claims from BP, Shell and their investors, fossil fuel generates astronomic profits. While consumers are locked into buying their energy, these revenues won’t fall, but if they actually wanted to help achieve net zero, there are valuable ways they could invest.

The Power project is currently working on a community-based project fitting a whole street in London with solar panels. The plan is for this street to effectively become its own self-sufficient power station, and to roll this model out further to “tackle the interlinked climate/energy/cost of living crises”. The other huge benefit of this project is that fitting a whole street brings down the cost of each panel to around £5,000 because of bulk discounts. By this logic, Mark Eris from the project has estimated that panels and professional installation would cost around £1m for a street with 100 houses. So, one billion pounds would pay for one thousand streets – in fact, probably more because bulk discounts would likely bring that figure down further.

As a signatory of the Paris Agreement, the UK has signed up to reduce emissions from heating and powering homes by 68% by 2030, and must reach net zero by 2050. Although retrofitting insulation to as many homes as possible has never been more crucial in reaching these goals, the UK’s 25 million homes (approx.) are also among the oldest and least energy efficient in Europe.

Significant research has been done into costing different approaches to retrofitting insulation. For example, the Climate Change Committee advocates spending £55bn by 2050 which would give 15 million households “one of the main insulation measures (loft/wall/floor)” and draft-proofing for another 8 million homes. The Construction Leadership Council proposes a tiered model that incrementally increases a mix of government funding with private capital year-on-year up to 2050. Another approach from the New Economics Foundation (NEF), proposes three funding models to retrofit the most critical 8.69 million homes over four years:

- Public-sector finance – £9,484/home = £93.56bn

- Private finance – around £13,801/home = nearly £124.2bn

- Mixed funding approach – average cost £10,461/home = £100.15bn

Of those three, the NEF report advocates the mixed funding approach because this creates “a large net gain in government revenue of £25.6bn” over four years, which equates to a return of “£1.74 for every pound spent”.

All three reports also note the significant savings to the NHS from reducing excess winter deaths as a result of cold homes – a tragedy that looks likely to significantly increase as the cost of energy rises. The reports also highlight an increase in government revenue from retrofit. The role of private investment in mixed funding approaches couldn’t be clearer and as wildfires rage, the cost of not acting immediately speaks for itself.

Time to rethink

At the time of writing, healthcare professionals and teachers have been out on strike and schools are falling apart. Years of austerity decimated public services and millions of people have been pushed to the brink by inflation and the cost-of-living crisis. Meanwhile, our planet is literally on fire and July 2023 was the hottest month on record. Although £131bn would not have ‘solved’ these ongoing crises in their entirety, rethinking what this sum might do through reinvestments that benefit us all isn’t an overly simplistic approach, because this figure only represents the dividends paid out to two British companies over just seven years.

Original artwork by Matt Tweed