Lendlease: development creeps

Lendlease is a global property developer and construction company based in Australia, with 12,000 employees working on four continents (Australia, North America, Europe and Asia). Its main speciality is large-scale “urbanisation” developments, often involving “Public Private Partnerships” (PPPs) with city authorities.

In the US, Lendlease is one of Donald Trump’s favourite building partners, responsible for the Trump Tower buildings in New York, Washington and Chicago. It is also well known for having paid up $56 million in “the largest construction fraud settlement in New York City history” in 2012; and for the deaths of two firefighters in the Deutsche Bank Tower fire. In both cases, Lendlease signed “non prosecution agreements” and avoided criminal charges.

In the UK, Lendlease is now in the news as the private partner in the £2 billion Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV) partnership with Haringey Council in North London. This follows on from its extremely profitable deal to gentrify the Elephant & Castle area with Southwark Council. For example, in the “One The Elephant” tower, LendLease made a £70 million profit on a site bought from Southwark for just £6.6 million – after councillors it wined and dined agreed to zero affordable housing in the block. Lendlease also built the new Wrexham mega-prison in North Wales – Europe’s second largest.

In Australia, Lendlease is the main developer of the massive Barangaroo site in Sydney – or “Lendlease town”. Community groups and the city’s mayor have protested as Lendlease has won backing from influential politicians to tear up public park plans and nearly double building space, adding three luxury apartment towers and a “six star” casino-hotel skyscraper.

Lendlease also runs Australia’s biggest retirement village empire, where elderly residents allege service cuts and fee hikes. Its subsidiary Capella Capital, meanwhile, leads on private prison projects among other “infrastructure” finance schemes.

To win developments, the company’s official sales pitch is that it can both oversee the building work and raise the finance. It has worked with many major Australian, Asian and global banks, and manages A$26 billion of real estate investment funds for over 150 “global institutional investors”. Lendlease’s shareholders are disguised behind “nominee accounts” run by big banks; the biggest one currently is the massive global investor BlackRock, with just over 5% of the company’s stock.

But perhaps Lendlease’s main superpower, wherever it goes, is its ability to make friends in town halls and state authorities. Planning rules are dropped, laws are amended, criminal charges fade away, and profitable development schemes creep over public space and social housing.

This report provides an overview of Lendlease’s company structure and activities; looks at its profits and who gains from them; then lists just some of many scandals and controversies it has been involved in worldwide. The conclusion summarises a few lessons about how this “development creep” works.

Company Overview

Lendlease started as a building company in Australia in 1958. It began to spread worldwide in the 1970s, first moving into the US construction industry. In the 1990s, its first well known UK scheme was the Bluewater shopping centre and housing development. In 1999 it bought Bovis, the UK-based global building company and notorious union blacklister, dramatically expanding its international presence. (“Bovis Lend Lease” was renamed Lend Lease Project Management and Construction in 2011.)

Lendlease’s head office is in Sydney, with regional head offices in London, New York, and Singapore. The biggest and most profitable part of Lendlease’s business – “urbanisation” development – is targeted on 17 international “gateway cities”: Sydney, Brisbane, Perth and Melbourne in Australia; Chicago, Boston, New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles in the US; London, Milan and Rome in Europe; and Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Tokyo, Beijing and Shanghai in Asia. However, more than 60% of its capital is still invested in its main base of Australia.

In Australia, Lendlease says it has “created more than 50 masterplanned communities over the last half century, with 16 currently in development”, as well as numerous high profile building and infrastructure projects. In the UK, before the recent Elephant & Castle scandal and the HDV, it was known for Bluewater and for the Stratford Athletes village. In Italy, one of its main business lines has been building PFI hospitals in Brescia and Treviso.

In Asia, major projects include the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and large-scale retail developments 313@somerset and Jem in Singapore. In the US, besides Trump hotels and other developments, it boasts of constructing the western hemisphere’s tallest residential building, 432 Park Avenue in New York.

Alongside “urbanisation”, the company has smaller infrastructure and investment divisions. Infrastructure – such as bridges and highways – is so far limited to Australia. Lendlease has an Australian subsidiary called Capella Capital, originally set up by a group of former ABN Amro bankers, which works specifically on arranging finance for infrastructure projects. Besides helping finance Lendlease-built infrastructure projects, this entity also works with other developers, notably on Australian prison privatisation schemes.

The investment division holds various assets for Lendlease’s own shareholders and for other investors in its “Real Estate Investment Trust” (REIT) vehicles. The company boasts of relationships with “approximately 150 global institutional investors including sovereign wealth funds, large public and private pension and superannuation funds and insurance companies.”

This property investment portfolio includes “the leading retirement living business in Australia with approximately 16,000 residents and 12,626 retirement units.” Another major investment is the 50 year “Privatisation of Army Lodging” (PAL) contract with the US Department of Defence to build and run 42 hotels for soldiers’ short term lodging on US military bases.

One new “emerging asset class” Lendlease says it is keen to develop is the “residential for rent product in London”. Historically, UK housing developers have made their money either by selling residential homes, or by selling or renting out shops and office space. Building major residential developments for rent is a new trend – as opposed to the US, where it is already well established. But as increasing numbers of, particularly younger, people, are priced out of the London property market, many developers are looking to cash in with “build to rent” developments and become super-sized private landlords.

Profits

(NB: unless otherwise stated, figures are in Australian dollars, which were worth roughly around 0.6 pounds sterling through most of 2017. The company’s reporting year ends in June, and the latest accounts were published in August 2017.)

Lendlease made a handsome profit after tax of $759 million in 2016-17 (around £455 million). They made $698 million the year before. Half of that profit was paid straight to shareholders as a dividend: the company has a set policy of paying an annual dividend of between 40-60% of profits.

The company’s global turnover was $16.7 billion last year (roughly £10 billion), showing growth of 10% from $15.1 billion in 2015-16. In both the last two years, it has made a healthy profit rate of slightly under 5% of revenue. It pays tax, with an effective tax rate of 24.7% last year and 19.1% the year before.

And the company looks to keep on growing. In its most recent annual report, the company said it had a development pipeline lined up worth $49.3 million. Investors have taken something of a more negative view of the company recently, after it sold a 25% stake in the retirement homes business at a loss and also announced declining turnover in its Australian construction business. For instance, stock analysts at Swiss bank UBS downgraded their recommendation on Lendlease shares to “neutral” rather than “buy”. But the company is still expected to turn a profit, and tighter margins in Australian operations could well be compensated for elsewhere if it keeps on landing windfall deals like Elephant & Castle or the HDV.

Unsurprisingly, most of the company’s revenue and costs are in the construction division: the bit that actually builds houses. Construction turnover was 12.6 billion last year, with profit (after tax) of 211.7 million. Equally unsurprisingly, the “development” and “investment” divisions, which sell properties and other assets or manage them for other investors, is where the real money is. The development division turned over $3.4 billion, but made a $397.8 million profit (12% of revenue); the “investment” division is even more profitable, making $381.4 million off just $566.7 million in revenue.

This is a standard pattern standard for big builder/developer companies. To land development deals with, for example, local mayors or councils, you need the capacity to manage big construction projects as a main contractor. But the profit comes from owning and selling properties yourself, not building them for someone else. This is an obvious reason why housing developers and their lobbyists are so keen on pushing “public private partnership” models, where the companies end up owning properties, rather than just building them on public authorities’ behalf.

In fact, Lendlease has stated “return on invested capital” (ROIC) targets of 9-12% for its developments, and 8-11% for its investment division.

Lendlease board 2016

Who gains?

Half of all that profit goes straight into shareholders’ pockets, while the other half is invested back in new developments. But who are the shareholders?

In Lendlease’s case, it’s not so easy to say. This is because the large majority of its shares are held through “nominee accounts”, in which stockbrokers hold and manage the shares on their unnamed clients’ behalf. In Lendlease’s case, most of the stockbroker nominee services are run by major global banks. As of the 2017 accounts, the top three were HSBC Custody Nominees (Australia) with 30.69%; J P Morgan Nominees Australia with 16.14%; and Citicorp Nominees with 6.94%.

Australian law, as in the UK, only obliges the company to name the actual shareholders if they own over 5% of the stock. In the 2017 accounts only one did: BlackRock Group, the massive global investment management fund which owns over $5 trillion (US dollars) in assets worldwide, which was listed as holding 5.01%.

Although the nominee structure means it’s hard to give a clear picture of Lendlease’s ownership, the basic picture is of a global corporation whose investors will be the same big investment funds, pension funds, banks and insurers who control much of the world’s capital.

As well as shareholders, Lendlease makes money for creditors who invest in its bonds or loans. As of June 2017 it had net debt (i.e., money it owes minus money it’s owed) of $912.8 million, paying an average annual interest rate of 4.9%, with debts due in an average of just over 5 years.

This includes bond issues in the UK, US, and Singapore as well as Australia. As well as bonds, Lendlease raises money through large “syndicated” and “club” loans: i.e., where a number of banks and other creditors split the loan between them. Currently, Lendlease has $2,225 million in “undrawn” loan facilities: i.e., they are similar to long-term overdrafts that haven’t actually been taken out yet, but are there as a back-up if the company needs cash. Lendlease has “investment grade” credit ratings (Baa3/BBB-) from global rating agencies Moody’s and Fitch.

As mentioned above, Lendlease’s investment division also manages “Real Estate Investment Trusts” (REITs), funds into which investors can place their money linked to a specific scheme or area. The company boasts of managing A$26.1 billion in 17 “wholesale property funds” for “approximately 150 global institutional investors including sovereign wealth funds, large public and private pension and superannuation funds and insurance companies.” 10 of these funds are invested in Australia, worth $18.9 billion. £852 million is managed in the UK, the rest in Asia (mainly Singapore).

Executive pay

One person who clearly does gain is CEO Stephen McCann. He received a total pay package of AUS $7.087m in 2017 (roughly £4.25 million). This included bonuses paid in securities valued at their current face value. Just his cash salary alone, before bonuses, was $2.034m (roughly £1.22 million). Two other executives had total packages valued over $3m, and another three over $2m. All these five had basic salaries over $1m.

Some controversies

Haringey Development Vehicle

In July 2017 Haringey Council in North London agreed on London’s most audacious “public private partnership” development scheme yet, called the Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV). Some £2 billion worth of public assets, including schools and the area’s biggest library, as well as council housing estates, will be transferred into a new corporate entity owned 50/50 by the council and Lendlease. This scheme is bitterly opposed by local residents and is currently the subject of a Judicial Review legal case. For much more detail see the StopHDV website.

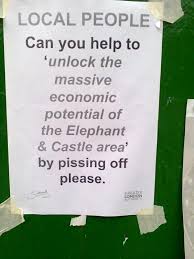

Elephant & Castle

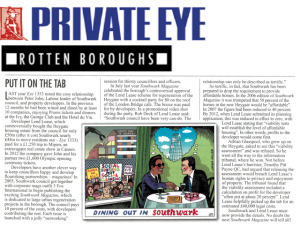

In 2007, Southwark Council appointed Lendlease as its “development partner” to redevelop the Elephant & Castle area, and began “decanting” residents out of the 1,194 home Heygate Estate. In 2009 Labour opposition leader Peter John described the-then Liberal Democrat council’s deal with Lendlease as “little more than throwing Heygate residents out of their homes and building new luxury housing which they won’t be able to afford.” In May 2010, Labour was back in power, and John signed the final “regeneration agreement” with Lendlease two months later.

In April 2013, Southwark Council accidentally published a document without redacting it properly, revealing that Lendlease had paid it just £50 million for the 22 acre site of prime central London real estate. This didn’t even cover the £65.4 million the council had spent on removing the residents and promoting the development.

In fact the last Heygate residents were only removed by bailiffs in November 2013, following six years of protests, legal challenges, planning hearings, alternative proposals, and compulsory purchase orders of resisting leaseholders. Council tenants were scattered away from the area, across Southwark and beyond. Leaseholders were offered compulsory purchase payments of as little as £80,000 for a one bedroom flat, or £225,000 for a three-bedroom ground-floor maisonette – the equivalent of which would cost around £1 million in Elephant Park.

Graffiti on the Heygate Estate, demolished to make way for Lendlease’s “Elephant Park” development

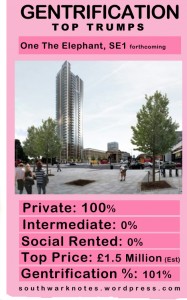

The council also sold Lendlease half of the site of the local leisure centre, for £6.6 million. Lendlease built a 37 floor skyscraper on this called “One The Elephant”. It has zero affordable homes. In place of affordable housing, Lendlease gave the council an extra £4.6 million “planning gain” payment. These payments did not cover the council’s £25 million cost of building a new leisure centre on the remaining land, half the size of the old one. All of the tower’s 282 properties were sold before completion, for a total of £185 million. Altogether, Lendlease spent under £110 million on the development, leaving a profit of over £70 million.

On the site of the Heygate, Lendlease’s “Elephant Park” development is due for completion by 2025. It will have 2,500 homes, as against the former estate’s 1,194. But only 74 will be for “social rent” equivalent to the former council homes – with another 500 at so-called “affordable” rent, which can be up to 80% of London’s inflated market rates.

These figures are well below the council’s own planning guidelines which specify 35% affordable rent, and 70% of that at “social” level. The council and Lendlease justify this discrepancy with a document called the “viability assessment”, made publicly available (in a redacted form) only after a three year legal struggle. This study assessed “viability” on the basis of Lendlease needing to make a 25% profit on the scheme. In addition, profits were estimated assuming homes sold for £600 per square foot: in fact, when sales began in 2015 they were going for over £1,000. Lendlease’s megaprofits from the former Heygate look likely to dwarf even those on One The Elephant.

In 2013, council leader Peter John faced investigation for failing to declare the gift of a £1600 Olympics opening ceremony tickets from Lendlease to his partner. Many more gifts from Lendlease to Peter John and other councillors – e.g., trips to a property fair in the South of France as well as proms tickets, dinners, and more – are correctly declared on the council website. Various other councillors and council officers involved in the Elephant regeneration saga have since become either Lendlease employees or private consultants working with them and their partners.

Old Broad Street tower glass fall

In July 2017, after a long court case, the High Court ordered Lendlease to pay £14.8 million after multiple plate glass windows fell off 125 Broad Street in the City of London, narrowly avoiding people below. Lendlease had refurbished the building between 2006 and 2008, and spent several years fighting the case so as not to take responsibility.

Prison profiteers

Lendlease’s website lists many examples of shiny new buildings, skyscrapers, concert halls and shopping malls. There is no mention, however, of a less glamorous part of the business: building prisons.

In 2014, Lendlease won the contract to build the first of the UK’s new generation of “mega-prisons”: the 2,100 prisoner HMP Berwyn in Wrexham, North Wales. It has also carried out work on HMP The Mount, notorious after recent riots.

In Australia, Lendlease is managing contractor on the Cessnock Correctional Centre in New South Wales, Australia.

Besides building prisons itself, Lendlease’s infrastructure finance subsidiary Capella Capital plays a key role in organising finance for Australia’s recent prison privatisation schemes.i These include the Ravenhall Prison “Public Private Partnership” (PPP), built and managed by US prison megacorp GEO but with Capella as “sponsor, financial advisor and bid leader”.

In 2015, a Capella-led consortium named Assure Partners completed the “Eastern Goldfields Regional Prison” (EGRP) redevelopment project in Western Australia, with a contract to get paid for running the prison for another 25 years. However, in 2016 Lendlease and partners sold their contract on to Australian pension fund and investment manager AMP Capital.

Union blacklisting

Lendlease is one of the major building companies involved in blacklisting trade union workers in the UK. Lendlease bought UK building company Bovis in 1999. The “Bovis” name was only dropped ten years later in 2011 – two years after “The Consulting Association” (TCA), the organisation which maintained the blacklist supported by leading building companies, was wound up after a police raid. According to a parliamentary report on blacklisting, Bovis was involved with TCA “at an early stage, but dropped out.” In 2016, Lendlease made an undisclosed settlement with former blacklisted workers after a case in the Hight Court.

Lendlease says on its website: “It is acknowledged that in the past, prior to the acquisition of Lend Lease EMEA by the Lendlease Group, a company within the Bovis group of companies (now known as Lend Lease EMEA) was involved in the issue of construction industry vetting. However the involvement of Lend Lease EMEA in relation to this vetting was minimal. Lendlease has settled all claims made against it by affected individuals. Lendlease confirms that it does not tolerate this activity.”

Retirement village discontent

All are not happy in Lendlease’s Australian retirement world. According to a recent (August 2017) report by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC): “current and former residents who have contacted the ABC say that after Lendlease bought their villages, services decreased, rules became more strict, and fees went up.” Examples include registered nurses and full-time maintenance staff being removed to cut costs, while in one case service fees were increased from $300 to $500. Residents can feel trapped as leaving a Lendlease village contract involves paying exit fees which can reach as high as $100,000.

In a separate report from 2016, retirees in one Sydney village were told their homes will be demolished to make way for a more profitable higher-density development.

Barangaroo: Crown casino-hotel and apartment towers

Barangaroo

Barangaroo is the name given to Sydney’s biggest redevelopment project, on a former dockland area in downtown Sydney. The original plan, agreed in 2006, was for a “public interest” development with over 50% parkland stretching along the whole waterline, and the tallest building standing 92 metres. Then in 2009 Lendlease was appointed “preferred developer” for the first phase of the plan and proposed major changes, including adding a skyscraper hotel built into the habour and substantially increasing building floorspace.

Over the next few years, Barangaroo became a political battle as former Australian prime minister Paul Keating championed Lendlease’s proposals for a much bigger and more profitable development, opposed by Sydney’s Lord Mayor Clover Moore and community groups. Keating and Lendlease also got other New South Wales politicians from both Liberal and Labour parties onside; the development was declared a “state significant site” out of the city council’s control; and state laws were changed allowing it to circumvent contamination rules.

The development grew bigger still when Australian casino mogul James Packer announced plans with Lendlease to build a “six star hotel” and “high-roller” casino targeting wealthy Chinese gamblers, on land planned as public park. At 275 metres, this will be Sydney’s second tallest building. Lendlease and Packer’s Crown Resorts company will also build three luxury apartment skyscrapers next to it, called “One Sydney Harbour” and designed by star architect Renzo Piano. The state parliament passed a special amendment to bypass casino licensing restrictions; the casino has also managed to get an exemption from the smoking ban and Sydney’s late night drinking laws. However, the agreement does impose conditions on Packer’s company relating to links to Stanley Ho, a Chinese casino boss accused of ties to Triad drug and prostitution rackets. In October 2016 18 Crown Resorts executives and associates were arrested in China as part of a Chinese state clampdown on the use of foreign casinos for money-laundering by corrupt officials.

In December 2016, Packer and Lendlease won a court decision to proceed after a challenge brought by Miller’s Point community groups and lawyers from the Environmental Defenders Office. The casino-hotel is scheduled to open in 2021.

The original Barangaroo development plan, drawn up by a team under architect Philip Thalis, has been modified at least eight times. Thalis now describes Barangaroo as “Lendlease town”, saying to The Guardian: “on what was once public land, we’ve ended up with … an exclusive outdoor shopping mall, an enclave of privilege and high prices”. Barangaroo’s building floorspace has nearly doubled from the original plan (from 389,511 sq m to 681,008 sq m).

James Packer (2nd left) with celebrity friends opening his Studio City resort in Macau

Safety allegations at Barangaroo

Lendlease’s Barangaroo development has seen a number of high-profile safety incidents. In the most serious, a man died after falling from scaffolding in January 2014. The CFMEU union claimed that the 23 year old was a trainee in a government supervised programme to employee Indigenous people who was left unsupervised.

In December 2016, a former health and safety manager at the site whistleblew to the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) alleging that Lendlease routinely covers up safety issues and fails to report incidents at Barangaroo. He alleged a culture of intimidation and bullying “driven from the very top of that project” down to supervisors who were “on many, many occasions instructed and bullied into submission, not to tell regulators, not to tell anyone else.”

Trump’s builder

In the US, Lendlease is one of Donald Trump’s main construction partners. The company has been the main building contractor in the following major Trump projects: Trump World Tower, Trump SoHo and Trump Place at Riverside South, in New York; Trump International Tower and Hotel in Chicago; Trump International Hotel in Washington.

In January 2017, the electrical contractor on the Washington hotel brought a $2 million lawsuit against Trump and Lendlease. They allege that Lendlease had witheld payment “at the Trump Organization’s direction”, after the contractors worked extra hours non-stop for 50 days to get the building ready for a presidential “grand opening”. By February 2017, another three sub-contracting companies had brought further lawsuits for unpaid bills. There have also been reports of a US Labor Department investigation after workers on the Washington site complained they were being paid below legal rates.

US: New York’s biggest ever property fraud case in 2012

In 2012 Lendlease agreed to pay up to US $56 million in penalties and restitution to victims after being found guilty in a New York court of systematic fraud over 10 years. Between 1999 and 2009, Lendlease’s US division routinely fiddled its hours to overbill customers. Projects included the September 11 memorial, Grand Central Station, New York Mets stadium, New Jersey schools, and court buildings in the Bronx and Brooklyn, including the courthouse where the case was heard. In addition, Lendlease defrauded the states of New York and New Jersey by falsely claiming that work was carried out by companies run by women and minorities, as required in their contracts.

This is reportedly the biggest ever construction fraud payout in New York. The case was described by FBI Assistant Director-in-Charge Janice K. Fedarcyk as “a systemic pattern of audacious fraud by one of the world’s largest construction firms”. Lendlease agreed to pay a $40.5 million civil penalty plus over $15 million in “restitution” to victims.

However, Lendlease managed to avoid any criminal penalties after making this “deferred prosecution agreement” which included assurances about its future good behaviour. Two US executives, James Abadie and John Byers, faced criminal charges which could have led to prison sentences. But they just got probation and fines of $175,000 and $15,000 respectively.

… and more “false claims” in 2015

Although Lendlease says it has cleaned up its act, it was back in court again in 2015 to make another settlement on a US “false claims”, this time in Virginia. In this case, Lendlease and its subcontractor Cindell agree to pay $400,000 to the US government to settle allegations from a whistleblower about subcontractors underpaying workers and then falsely “certifying compliance on weekly certified payrolls.” Again, the settlement meant that no criminal charges were brought.

New York Deutsche Bank tower fire

Another ongoing court case in the US sees Lendlease taking on two New York firefighters. In August 2007, two firefighters were killed and around 100 injured during a fire in the Deutsche Bank Tower near the “ground zero” site of the 9-11 attacks, which Lendlease was contracted to demolish.

Investigators found that Lendlease was responsible for major safety errors such as cutting away part of the water standpipe system that was needed to supply firehoses, and nailing plywood barricades across stairwells which led to firefighters becoming trapped. However, once again Lendlease avoided criminal charges by agreeing to a “non prosecution agreement” in which it created $5 million memorial funds for the dead men’s families. Thanks to this agreement, under which Lendlease “neither admits nor denies any criminal or civil liability”, its lawyers carry on fighting claims for damages from other surviving firefighters.

Protest at Lendlease Elephant & Castle showroom: “the ruins of the Heygate will come back to haunt you”

Conclusion: how development creep works

Lendlease is certainly not the only developer doing lucrative gentrification deals with city authorities. But not many manage to pull off such breathtaking schemes on opposite sides of the world at once. The Elephant & Castle and Barangaroo developments are both textbook examples of ‘development creep’: in which an initially “public interest” project morphs over time into a private profit goldmine. Here we recap a few key features in both deals:

- 1) Win people over. This stage involves architects and consultants working with the local authority and carrying out public consultation, to draw up people-friendly proposals including improved public space, social housing and other amenities. Anyone objecting at this point can be made to look paranoid.

In Barangaroo: the original plan launched in 2005 featured over 50% public park including the whole shoreline, and no buildings over 92 metres.

In Elephant: the 2004 masterplan featured 1,200 “social rented” homes to replace the number on the Heygate Estate, as well as a new theatre, museum, library and secondary school.

- 2) Make gradual changes. Once the developer is appointed, the initial plan is changed to make more money. Changes can be introduced gradually, one ‘creeping’ step at a time. It is near impossible now to get rid of the developer.

In Barangaroo: there have been eight waves of proposed modifications, between them almost doubling the amount of saleable floorspace, dramatically reducing the public space, and adding three luxury residential towers and a skyscraper casino-hotel.

In Elephant: the actual Lendlease scheme now only has 74 social rented flats plus 500 at so-called “affordable” rents. The theatre, museum, library and school are forgotten – but there is a hipster “box park”.

- 3) Batter down the arguments. There are numerous ways changes can be justified, and whole teams of consultants may be employed writing lengthly reports to do so. For example, changes may be necessary for “financial viability”. Also, developers and authorities may back down on a few of the more outrageous proposals, which makes it seem like resisters have won concessions and developers are being reasonable.

In Barangaroo: Lendlease’s first big shock was proposing a skyscraper hotel built into the bay itself, against public shoreline planes. They backed down on this plan after serious opposition resistance – before introducing the even bigger casino-hotel proposal, albeit away from the shoreline.

In Elephant: the viability assessment, released after a three year legal battle, showed affordable housing cuts were based on the “need” to give Lendlease a 25% profit on the deal.

- 4) Get the politicians on side. But ultimately, it’s not moaning residents who make the decisions, but their elected leaders. They can even change rules or grant special exemptions if necessary.

In Barangaroo: not only planning and affordable housing policies, but regulations on gambling, smoking and late night drinking, were changed or exempted for the Lendlease scheme.

In Elephant: Southwark council’s rules on 35% affordable housing were repeatedly overidden by council bodies, including allowing zero affordable housing in the “One The Elephant” tower which made Lendlease over £70 million profit.

- 5) Make friends in every party. The process takes years, and political power can change hands in the meantime, so clever developers may aim to win over politicians from different sides.

In Barangaroo: Australia’s Labour Party lost the New South Wales election in 2011, ceding control to the Liberal Party. Their leader Barry O’Farrell promised a review of the development, which called for some minor amendments but left the planning approvals unchanged. Bridie Jabour, writing in The Guardian, has documented how Lendlease’s casino-mogul partner James Packer of Crown Resorts has employed NSW Labour figures Karl Bitar and Mark Arbib as lobbyists, while appointing former Liberal senator Helen Coonan to the Crown board.

In Elephant: Lendlease was first selected by a Liberal Democrat council under leader Nick Stanton and deputy leader Kim Humphires – both of whom have since got jobs as property development consultants. Then Labour leader Peter John slammed the deal as “little more than throwing Heygate residents out of their homes and building new luxury housing which they won’t be able to afford.” Then, a few months after Labour took over in 2010, John himself signed off on the Lendlease scheme. He has since faced investigation for accepting an undeclared gift from Lendlease.

Lib Dem leader Nick Stanton with Lendlease’s UK CEO Dan Labbad

Labour leader Peter John with Lendlease’s UK CEO Dan Labbad

We doubt it is coincidence that these common patterns appear in developments from Sydney to London. But it’s certainly worth people touched by the HDV or other Lendlease schemes to be prepared for these kind of moves. Or anyone affected by development in general: Lendlease is certainly not the only developer using standard techniques to up its profit rates.

A few current UK projects

Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV)

Elephant & Castle: One The Elephant, Elephant Park, Trafalgar Place (see details below)

Stratford: “International Quarter London” (50% joint venture)

York: Hungare Regeneration (50% joint venture)

Victoria Drive, Wandsworth residential development

Timberyard Deptford (with London Borough of Lewisham)

Northamptonshire County Council Framework

Kings Cross Google HQ

St Johns Wood barracks development (also here)

Liverpool John Moores University site (now scrapped after cost rises)

“Scape”: UK-wide national procurement framework contracts

iOn its website, Capella presents itself as a separate entity that has a “relationship with Lendlease”. But in fact Capella Capital is a wholly owned subsidiary of Lendlease – as is made clear in Lendlease’s consolidated accounts (see 2017 Annual Report page 170).