Mears Group: scandal-hit council housing profiteer turns asylum landlord

[responsivevoice_button]

Mears is an outsourcing company working in two sectors: housing management, and home care. It has recently won the £1.15 billion Home Office contract to provide asylum seeker housing in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Yorkshire and the North East of England.

So what sort of company is Mears? Corporate Watch has looked into Mears’ past record to find how the “strong sense of social responsibility” its promotional materials boast plays out in practice.

Mears presents itself as a step up from notorious outsourcing rivals like Serco and G4S. But it is far from certain the company can be trusted to provide decent homes for refugees.

- Mears is being hit by multiple scandals. Its flagship regeneration contract in Milton Keynes may be collapsing amid allegations of overcharging for repairs, while it has recently been dropped from a big repairs deal on its home turf of Gloucestershire. Allegations involving overcharging scams and corruption hang over deals from Brighton and Scotland. Most shocking of all: in 2017 Mears tried to ban beards.

- The Mears home care business struggles to break even and to keep care workers, unsurprising given the infamously low rates of pay in the sector. Over 40% of Mears’ care workers left the company last year.

- Meanwhile, Mears’ top brass receive handsome rewards. The company paid out £52 million out to its shareholders over the last five years, while CEO David Miles made £443,000 last year — over 20 times the average wage for Mears workers.

- While profits and payouts remain healthy, Mears’ financial profile shares many similarities with those of troubled outsourcing firms such as Interserve and Carillion, with potentially few resources to fall back on if contracts are lost or government spending is cut further.

- Mears’ current Chief Operating Officer, John Taylor, was previously boss of scandal-hit housing company Orchard & Shipman — when that company won the bid to run much of the previous Scottish asylum housing contract under Serco.

- To keep growing, Mears is expanding into new business lines, such as building its own housing developments and running its own regeneration schemes. It also manages the National Planning Portal, which processes most of the UK’s planning applications, and last year it bought rival outsourcer Mitie’s social housing division. In January 2019 Mears won its biggest deal yet — £1.15 billion worth of asylum housing contracts with the Home Office.

Do you have information about Mears you’d like to share with us? Click here to get in touch.

Main picture: a Mears sponsored networking event with senior council and housing association managers.

Click on the heading below to go straight to a section:

- History: council housing profiteer

- Housing

- £1.15 billion Asylum Housing Contract

- “Blurring the boundaries between private and social”

- National Planning Portal

- Home care

- Scandals: Milton Keynes regeneration, Brighton overcharging, Scottish corruption allegations, Stroud repairs, Apprenticeships, Industrial disputes, Beards

- Company people

- Shareholders

- Finances

Mears is one of the UK’s biggest maintenance and repairs contractors, working on over 650,000 homes for councils and housing associations. Mears home care division provides care to 15,000 older and disabled people.

The company employs 12,000 people. It is based in Gloucestershire, but works all over the UK.

Mears’ shared are listed on the London Stock Exchange. Its businesses bring in around £900 million a year.

History: local privatisation profiteer

Like G4S, Serco, Capita and other well-known “outsourcing” corporations, Mears Group has grown from the ongoing privatisation of public services. But whereas G4S or Capita have profited from the sell-off of national services, Mears has thrived in the smaller and less visible world of local government privatisation.

Until the 1980s, “social housing” was very largely the responsibility of elected Local Authorities. Council housing was not just owned and managed by Local Authorities, but maintained and repaired by local in-house teams. These “Direct Labour Organisations” (DLOs) made no profit and recruited and trained people to maintain the housing stock.

This model of local public provision was attacked by Conservative and Labour governments from the 1980s on. Legal changes and budget controls pushed the privatisation of council housing in a number of ways, including “Right to Buy” sales and the mass stock transfer of around 1.9 million homes from councils to housing associations. Another was pushing councils to contract out repairs and other services to the private sector.

This included “compulsory tendering” rules that forced authorities to hire low-cost contractors who undercut their in-house teams. More broadly, it involved a spreading ideology of privatisation: repeating the mantra that private companies were more “efficient” at running services. Of course, this personally benefited many local politicians and managers who moved into well-paid private sector jobs.

As many authorities closed or sold off their DLO maintenance departments, the winners were contractors like Mears.

Housing

Mears’ housing business falls under three headings: maintenance, management, and development.

The bread and butter business is winning council and housing association contracts for maintenance and repair work.

According to its latest annual report, Mears works on “over 14% – over 650,000 – of the social homes in the UK”. In some cases, for example in Manchester or North Lanarkshire, Mears works through joint venture companies set up together with local authorities. This division still makes up over three quarters of Mears’ housing business.

But maintenance margins are tight. The business model is based on trying to undercut councils’ and social landlords’ “in house” services; and there is competition from several big national rivals, as well as smaller local companies. In a June 2018 presentation, Mears identified four major housing maintenance competitors: Wates, Fortem, Kier (click here for our profile of them), and Mitie Property Maintenance, which it has since bought.

To increase margins, Mears is trying to break out into wider “management” roles. So far, Mears has overall management responsibility for some 10,000 properties. Almost 3,000 of these are run by Mears’ two “non-profit” subsidiaries Omega and Plexus (see section below). Mears also offers a range of management services to other landlords, such as “income management” (i.e., rent collection), and “emergency accommodation”.

Mears also sees the overlap between its housing and care businesses as a good selling point – looking to capitalise on an ageing population. Its “housing with care” schemes involve running sheltered housing with carers on call.

Finally, Mears has also started to develop and build houses itself, particularly as part of regeneration schemes. The Mears New Homes division was set up in 2014.

A related business line is “property acquisition funding”. Mears buys up properties, does them up and sells them on to “a long-term funding partner”, perhaps after a few months. It has set up a £30 million fund for this sideline.

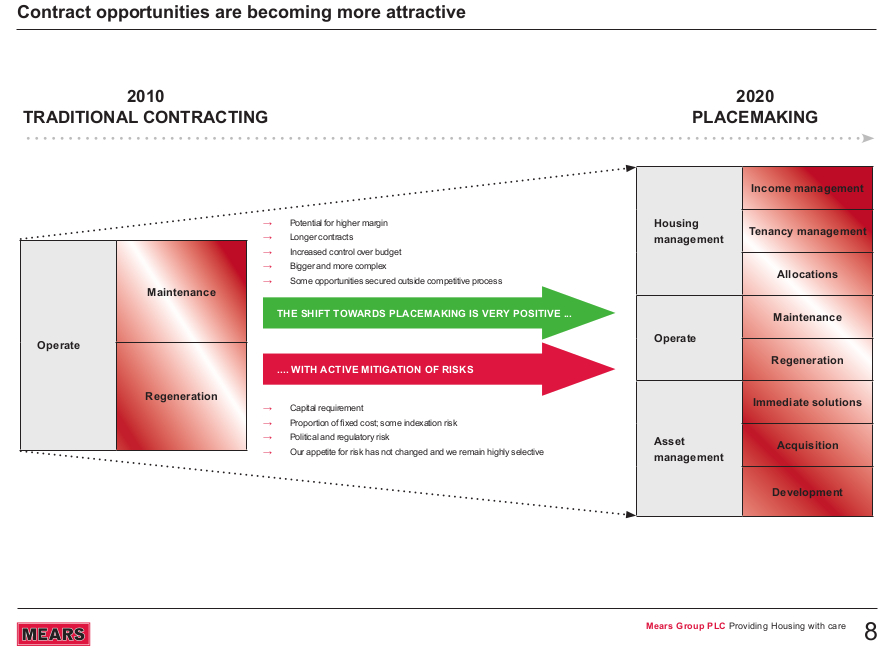

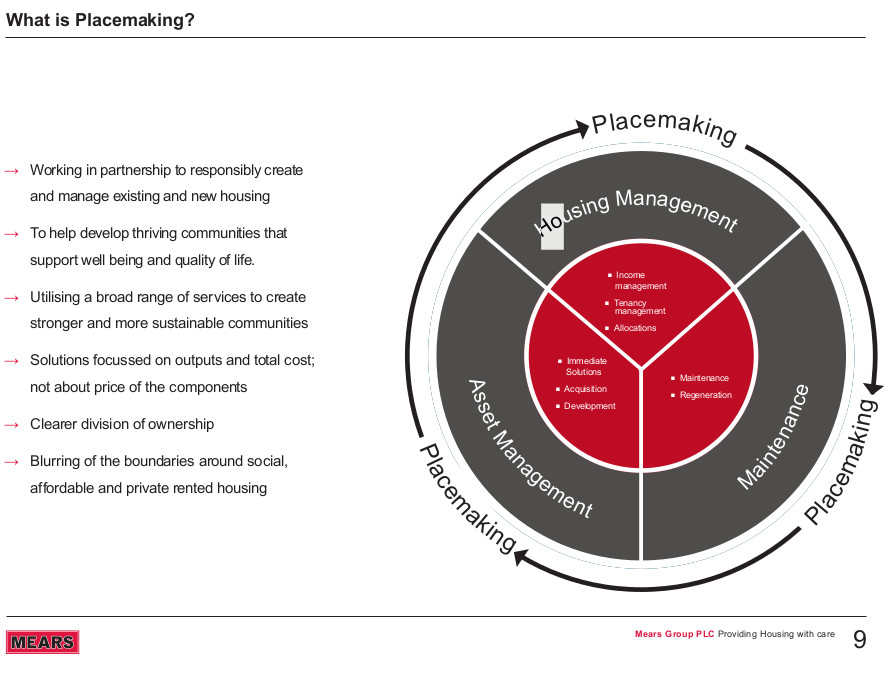

To describe its new business approach overall, Mears likes to use a current regeneration buzzword – “Placemaking”. It explained what this means in a June 2018 investor presentation.

According to this document, Mears’ approach combines maintenance, housing management and “asset management” in deals that are “bigger and more complex”, with “potential for higher margin” and “some opportunities secured outside competitive process” (we are not exactly sure what that last phrase means).

Placemaking also involves: “blurring of the boundaries around social, affordable and private rented housing”. We will discuss this point further below.

Mitie buy-out

Through the years, Mears has grown steadily by picking up outsourcing contracts from both councils and housing associations, taking over former DLOs and buying out competing maintenance businesses.

Its biggest acquisition yet was announced in November 2018. Mears agreed to buy Mitie Property Management, the social housing management wing of outsourcer and detention profiteer Mitie, for £35 million. (See our 2018 company profile of Mitie here.) Mitie Property Management has over 1,000 staff and contracts with more than 30 landlords, bringing in annual revenues of £138 million.

However, Mitie Property Management has been one of the worst performing parts of Mitie’s business, which the company has been looking to get rid of for some time (click here to read more in our 2018 Mitie company profile). But for Mears, this will mean taking one of its main competitors out of the game.

Image: Glasgow asylum housing run by previous sub-contractor Orchard & Shipman, whose old CEO now works at Mears.

Big government deals – the Asylum Housing contract

In an investor briefing last year, Mears’ management said they had decided to turn their focus to bigger deals, particularly from central government: “Evolution of business means we are gaining access to opportunities previously out of our reach.”

In particular, Mears worked on two big government tenders in 2018. One, now in the bag, covers major Home Office asylum housing contracts for Scotland, Northern Ireland, and North East England, Yorkshire and the Humber. Together they are worth £1.15 billion over ten years.

These contracts involve providing housing for thousands of asylum seekers who have been “dispersed” to those areas by the Home Office while they apply for refugee status. In practice, the accommodation is rented from a wide range of housing associations and smaller private landlords, with Mears acting as the overall manager.

This is the first time Mears has worked as a refugee landlord. In Scotland, Mears takes over from the previous manager, Serco, after a strong local campaign against that company’s attempts to evict 300 refugees from their homes in Glasgow. A court case challenging the evictions is currently in progress. In Yorkshire and the North East, Mears is replacing G4S – whose asylum housing has been notorious for squalor, infestations, and scandal when racist vigilantes attacked homes whose doors had been painted an identical red colour.

While this is a big new income source for Mears, asylum landlords have not always had an easy ride financially. Both Serco and G4S complained of losing large sums of money on the previous deals. Financial information on the new contracts has not yet emerged and we do not know if the government bowed to the contractors’ demands to increase payments and profit levels.

There are few specifics yet about how Mears will run the new contracts – and so whether there’s likely to be any change from the miserable record of G4S and Serco.

One notable point: from September 2012 until 2016, Serco’s Scottish asylum housing was largely sub-contracted to another scandal-hit company, Orchard & Shipman. Mears’ current Chief Operating Officer, John Taylor, was Chief Executive of Orchard & Shipman when they won the deal working with Serco. He then moved to Mears in 2013. Presumably his experience will have helped with Mears’ bid for the new contract.

For more information on the new asylum housing contracts see our recent article.

For background on the previous contracts, and on the asylum housing system overall, see The UK Border Regime chapter 5. The Unity Centre in Glasgow and SYMAAG in Yorkshire are two groups actively supporting the struggle for decent housing for refugees.

Ministry of Defence bid

Mears’ other big government tender was less successful. It had hoped to take over the contract to run much of the Ministry of Defence’s main accommodation estate in 2018, after Carillion went spectacularly bust. Mears lost out to rival outsourcer Amey. Mears does have another smaller MoD contract – since 2016 it has run the military’s “substitute service family accommodation”, to find private sector housing for military personnel.

“Non-profit” subsidiaries: “blurring the boundaries” of private and social

One important trend in the UK housing world is the convergence of “private” and “social” sectors. Mears is an enthusiastic part of this. As mentioned above, it boasts that one of the key features of its “placemaking” business strategy is:

“Blurring of the boundaries around social, affordable and private rented housing”.

What exactly does this mean in practice? To start with, Mears has two “affordable housing” subsidiaries called Omega Housing and Plexus UK (First Project). Both are wholly owned by Mears and are registered with the government’s Social Housing Regulator as “social housing providers”. They are listed as “non profit” but are companies limited by guarantee rather than charities. At the end of 2017, Omega managed around 1,000 properties, and Plexus over 1,700. In addition, Mears stated in a June 2018 investor presentation that a “key priority” is to also achieve Registered Provider status in Scotland.

Just what is a profit-seeking company doing running “social landlords”? While technically “non profit”, these subsidiaries can help other parts of the business make money. This comes across clearly from Mears’ website page on its “affordable housing” operations. Councils often require new developments to include a proportion of “affordable housing” in order to meet planning stipulations, called “section 106” agreements. Mears is clear about how Plexus and Omega can play this role, saying that its affordable housing arms “assist and support developers on section 106 agreements.”

Secondly, the “affordable” subsidiaries can be used to access public grants:

“We work with investors to purchase stock where we can secure long leases at affordable rents and can utilise Local Authority funding in addition to leveraging in private institutional funding.”

Thirdly, they will help develop relationships with key “partners”, such as local councils, who Mears may also work with on more profitable developments. Mears can offer a suite of services to its partners, from high-end luxury sales to temporary accommodation for the homeless.

In particular, one model Mears is pushing is converting empty commercial property, such as old offices, into “affordable housing”. For example, in recent developments in Luton and Basingstoke.

The National Planning Portal

One Mears subsidiary, called Terraquest, is unlike other parts of the business. It deals in information. Terraquest’s main work is “land referencing” – researching and identifying rights over property, including ownership rights but also things like planning permission. It also has other business lines including employer security checks.

How does Terraquest fit into Mears’ strategy? Most obviously, as it says on its website, Land Referencing is a crucial tool for property developers – it “enables developers to acquire land and rights over land to meet their development requirements in a timely manner.”

But there may also be something more. Mears’ business is above all about “partnership”, making joint ventures and contracts with other developers – especially government bodies, councils, and housing associations. Many of these are Terraquest’s customers.

Mears/Terraquest’s biggest coup is running a big piece of the whole UK planning system: 90% of all planning applications in England and Wales (according to a Mears presentation) go through one internet system called the National Planning Portal. If you try to submit a local council planning application online, you will probably be redirected there. The national portal is set up by the government’s Ministry of Homes, Communities and Local Governments. But it is run privately by a joint venture – which is 75% owned by Terraquest.

There is no suggestion that Mears uses the nationwide planning data it manages to gain an unfair advantage in its own developments. But, at least, providing this service must give it a real familiarity with the planning system and how it works across the country.

Home care

Mears’ first attempt to make money from old and disabled people’s need for care at home came in 2007 when it bought a home care company called Careforce. More acquisitions followed – most notably Care UK’s home care division in 2015 – and by 2015 Mears had become the second biggest home care provider in the UK.

However, the ‘market’ has not been as profitable as Mears hoped. Most of Mears’ contracts are with cash-strapped local authorities. Even with infamously low wages being paid to staff, many contracts do not pay enough for companies to break even.

As a result Mears has had to scale back its ambitions. It finally turned a – very small – profit on home care in 2017, after it had closed a fifth of its branches, mostly in the north of England. Mears now provides care for 15,000 people a year. Its revenues from this in 2017 were £134 million, down from £152 million the year before. The company says it is still trying to grow its home care business but only with contracts that “can provide clear and sustainable margins” (in other words turn a profit).

When we investigated Mears in our Home Care Business report two years ago, we found the company appeared, on the whole, to be providing a better service than its for-profit rivals. However, there were still instances of appalling care. Failings in one branch saw people left without medicine and meals.

We also found that while staff pay at Mears may have compared well to that at other major home care companies, it was still barely above minimum wage. Mears says its care workers are paid above minimum wage and that “it is central to our strategy that care workers are properly recognised as the skilled workers they are”. However, staff turnover remains, in Mears’ words, “unsustainable”. A massive 42% of staff left the company in 2017.

A few recent scandals

While it has enjoyed recent success winning big contracts, things haven’t been going so well for Mears in the deals it already has. Its flagship regeneration contract in Milton Keynes may be hitting the skids, while it has recently lost a major deal in its own home turf of Gloucestershire. Meanwhile, allegations of overcharging scams and possible council corruption hang over deals from Brighton and Scotland.

Milton Keynes regeneration vehicle

YourMK is, or was, Mears’ flagship regeneration project: a £1 billion “partnership” with Milton Keynes council to redevelop seven major estates over 15 years, affecting 8,500 homes. Mears likes to boast about this scheme. For example, a slide in a June 2018 investor presentation gave a list of “housing challenges”. For all of these, the solution was, of course, Mears, “evidenced by .. YourMK”.

The scheme is a 50/50 Joint Venture with the council. Set up in 2015, it initially had the relatively straightforward aim of maintaining the council’s existing stock. But it was soon clear that the “Placemakers” at Mears were thinking well beyond just doing repairs. A Mears “think tank” brochure from 2016 flags up ideas for a “mixed market approach” involving “bond finance”, “private sale”, and “scope to create [a] subsidiary vehicle that could deliver funding over 30-40 year term”. All of which could be very profitable for Mears and other private sector partners.

But, less than two years into the scheme, the wheels started to fall off. Residents on the first estate targeted, Fullers Slade, protested at being “let down and ignored” by YourMK. The council put the regeneration scheme on hold in January 2018. And in July, the council made a number of U-turns to bring “community engagement”, “neighbourhood employment”, and repairs management teams back in-house to council control.

Mears is still employed as repairs contractor but now under council management and with its work “clearly badg[ed] .. as undertaken by Mears Group PLC” to “remov[e] confusion for tenants”. The council also announced it would change the “structure, operation and senior management of Your MK”. It is not yet fully clear what this will mean for the partnership with Mears.

Things got even worse for the deal in October 2018. According to the Milton Keynes Citizen, the council asked its auditors to investigate allegations that Mears had overcharged for repairs by up to £80,000 a month, and that £15 million of council money is “currently unaccounted for” by Mears. The Citizen reports council leader Peter Marland saying:

“The council received a whistleblowing allegation regarding spending on our housing repairs contract. We have asked our external auditors to investigate fully, as is right, to establish if the allegation has any basis and will act accordingly.”

A Mears spokesperson said: “Mears does not in any way recognise these claims and are not aware of any audit being undertaken within the council. Mears operates transparent accounting in all of our public contracts.”

At the time of writing, the YourMK website has been closed down, with a page announcing that information will be updated in April 2019.

Click here to contact us if you have any further information about the YourMK partnership or Mears’ activities in Milton Keynes.

Brighton overcharging scandal

The Milton Keynes deal is not the first time Mears has had to deal with overcharging allegations, or with whistleblowers.

Another big Mears’ contract is the £200 million, ten year housing maintenance deal with Brighton and Hove City Council (BHCC), which began in 2010. A council investigation found that it had been overcharged by over £500,000 for some 1,000 plastering jobs. The overcharging came from another company sub-contracted by Mears but the council’s audit review found that “it had not been picked up because of insufficient control mechanisms operated by Mears.” The council’s report also acknowledged a general “break down in trust” between the council and Mears. But the plastering scam was not an isolated incident.

In 2016, the Brighton Argus reported residents’ complaints of “being charged up to £30,000 at twice the cost advised by independent surveyors.” And in October 2017 the council started a new investigation into further overcharging “discrepancies” with electrical work carried out directly by Mears. This is “estimated to be in the order of six figures again”, according to the Brighton and Hove News.

At the time of writing, Mears is still working in Brighton. But the contract will come up for renewal or retender in 2019.

Picture: from Brighton & Hove Housing Coalition

Scottish corruption allegations

In Scotland, Mears has a major contract with North Lanarskhire Council, worth an estimated £445 million over ten years, to maintain the council’s 36,500 council homes, as well as schools and public buildings.

The contract started in January 2011, as a “partnership deal” between the council and a company called Morrison Facilities Services Ltd, a subsidiary of Anglian Water. In 2012, Mears bought out Morrison and took over the deal. The joint venture is now called “Mears Scotland”, with Mears holding 67% of the stock and the council 33%.

The managing director is Willie Docherty, whose wife Sadie Docherty was Lord Provost of Glasgow between 2012 and 2017. Before joining Mears in 2012, Willie was head of Glasgow’s “arms length” company City Building, which was spun-off from the city council’s old building services department – and became embroiled in scandals over awarding contracts to several Labour Party donors.

In January 2015, North Lanarkshire’s Labour council hit a crisis, as one Labour councillor named Tommy Morgan was sacked from his role as chair of the “audit and governance panel”. Scottish media reported allegations that he had been ousted for “asking awkward questions” about the Mears contract. Later, Morgan said he was suing the Labour Group over the issue.

In July 2015, council leader Jim McCabe was reported by opposition councillors to the Public Standards Commissioner. According to the Scottish Herald, Mears had “just secured substantial concessions in its housing repairs contract with the council – costing the authority some £25m,” while “a report from the council’s own auditors, accountants Scott-Moncrieff” said “councillors had not had full facts before deciding not to re-tender the deal.” An SNP councillor then asked the Commissioner to investigate whether McCabe had failed in not declaring his personal friendship with managing director Willie Docherty.

The Commissioner’s investigation cleared McCabe, concluding that his actions “did not amount to a contravention of the Councillors’ Code of Conduct.” McCabe resigned from the council in January 2016, after 18 years as leader. Later that year, the chief executive of North Lanarkshire asked police to review separate claims that McCabe had been on a holiday to Turkey with another Mears executive, Steve Kelly. McCabe insisted: “all holidays I have been on, I have paid for. And I can prove that beyond any doubt.” McCabe did take gifts of dinners, whiskey and chocolates from Mears, but these were legally declared on the council’s website. A separate investigation by Audit Scotland also concluded that the council’s accounting of money payments in the Mears contract was not illegal.

In short: allegations have flown thick and fast around the Mears Scotland contract, and there is no doubt that the council leader was close to Mears executives. But there is no evidence of any illegal wrongdoing.

The Mears Scotland contract will be up for renewal in 2020.

Picture: Mears Scotland promotional photo, Willie Docherty is standing, on the left.

Repairs problems in Stroud and elsewhere

In 2017, Stroud Council, in Mears’ own county of Gloucestershire, cancelled its £4 million maintenance contract with Mears after just one year. The contract began in 2016 and was set to last for up to 10 years. According to local press, Mears agreed to end the contract after “heavy criticism about its council housing repairs and maintenance work”. A council spokesperson said “Mears were unable to maintain the high standards we demand of our contractors, and also found elements of the contract commercially challenging.”

Other areas where complaints about Mears have made the news for the wrong reasons include the London boroughs of Walthamstow and Islington, where they work for Family Mosaic housing association (now part of Peabody Group), and also Cornwall.

Apprenticeship inspection

Mears prides itself on having an educational role. In the latest (2017) annual report it describes itself as “a national Social Mobility Champion and leading employer of apprentices”. In 2017 it had 345 housing apprentices and 224 care apprentices.

However, the education inspectorate Ofsted gave the “Mears Learning” division, which runs apprenticeships in the company, a negative rating of “insufficient progress” in its report in May 2018.

Industrial disputes

The trade union Unite announced victory in its strike over a pay dispute with Mears in Manchester in February 2018. According to the union, workers at Manchester Mears and Manchester Working (a joint venture with the council) “were being paid up to £3,500 less than colleagues for undertaking the same work”. The company agreed to raise and equalise wages after 80 days of strikes.

Beards row

In June 2017 Mears made headlines when it tried to ban workers from having beards. It told maintenance teams they needed to shave in order to “wear appropriate dust masks effectively”. Unite the Union accused Mears of “penny pinching stupidity”, saying it should just pay for better dust masks that can cover beards.

People

Mears’ long-time chairman Bob Holt was recently pushed out by the second biggest shareholder, German investor Shareholder Value Management. It alleged Holt – who cut his business teeth working for notorious Tory donor Lord Ashcroft – had “continually failed to challenge the status quo” of “deteriorating results, a stagnant share price and faded shareholder value”. Holt was paid £285,000 for 2017.

His replacement, Kieran Murphy, is an investment banker rather than a builder. Murphy started his career as a Treasury civil servant in the 1980s before heading into the private sector working with German investment bank Dresdner Kleinwort. There he became a managing director and “head of industrial sector”. He then worked from 2004-15 as a partner and “senior advisor” at Gleacher Shacklock, a corporate finance consultancy set up by another ex-Dresdner banker. His career has been advising businesses on financial deals such as raising money or buying other companies.

Nowadays, Murphy sits on the boards of large “public sector” organisations as well as private companies. He is the chairman of the Ordnance Survey, the government mapping service – which could be useful for Mears’ work running the National Planning Portal. He is well connected in the university world, as a former director of City University and now of the University of London. He also chairs the investment committee at University College London hospital. Of course, these institutions are also big property owners and developers in their own right.

In: Kieran Murphy

Out: Bob Holt

Chief Executive: David Miles

Miles is a long-term Mears manager. An electrical engineer by trade, he worked at Mitie back in the 1990s but joined Mears in 1996 when it went public. He ran Mears’ social housing division and was “chief operations officer”, before rising to CEO in 2010.

Miles was paid £443,000 in 2017. Miles’ 2017 pay included a basic salary of £369,000 plus £55,000 pension contribution and £19,000 “taxable benefits”.

But he was also eligible for a bonus on top of his salary of up to £774,000, which would have taken his income well over the million mark. However, his bonus pay is linked to the company’s financial performance, and with Mears’ finances slightly reduced from the previous year, Miles didn’t get any of his bonus in 2017. In fact, he hasn’t made anything like his possible top bonus in the last four years.

Still, his £443,000 was more than 20 times the average Mears employee’s salary of £21,684.

David Miles

Other executives

The finance director, C.M. Smith, and executive director Alan Long are also Mears stalwarts, having worked at the company for 18 and 12 years respectively. They were paid £294,000 and £248,000.

John Taylor, Chief Operating Officer, is a newer arrival. Until 2012 he worked at Orchard & Shipman, another “property management company”. Notably, Orchard & Shipman were sub-contracted by Serco to run much of their asylum housing contract in Scotland between 2012 and 2016. This is effectively the same contract that Mears have now taken over from Serco.

A few non-executive directors

Mears’ strategy involves networking across the “blurring boundaries” of high finance and charitable housing provision. This is reflected in the “non-execs” on the board, who are plugged in to these different parts of the regeneration industry.

To give a few examples, non-executive director Julia Unwin is a high-flyer in the charity sector who also has a foot in the privatised water business. She is former Chief Executive of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust and also now a director of Yorkshire Water.

Elizabeth Corrado is linked to the booming world of “social finance”, where investment banking meets “philanthropy” – for a profit, of course. According to her Mears profile she has worked as an investment banker and government advisor on structured finance, and was “until recently an Executive Director of the Power to Change charitable trust”.

Roy Irwin was the Chief Inspector for housing of the Audit Commission, the official body which audited local councils’ finances – until it was scrapped in 2012, with its functions privatised. He then found a home at Mears in 2013, becoming Chairman of its “social landlord” businesses Omega and Plexus. In 2017 he also joined the board.

Shareholders

Mears’ shares are bought and sold on the London Stock Exchange. As a result a range of different investors own stakes in the company. At the time of writing, the top five biggest stakes are held by investment funds:

PrimeStone Capital LLP 12%

Shareholder Value Management AG 9%

Majedie Asset Management 9%

Heronbridge Investment Management LLP 7%

Schroder Investment Management Ltd 5%

Most companies on the stock market have similar ownership profiles, with no single investor having close to a majority stake. As a result, while a company may be acting primarily in the interests of its shareholders, responsibility for its actions is difficult to lay at the door of any one shraeholder.

However, Mears’ two biggest shareholders see themselves as ‘activist investors’ that involve themselves in the running of their companies.

Mayfair-based PrimeStone Capital describes itself as working “constructively with management and stakeholders to create long term enduring value.” Primestone was founded by Franck Falezan, Benoît Colas and Jean-Pierre Millet, three financiers previously with The Carlyle Group, a major US venture capital firm.

Shareholder Value Management (SVM) is a German investment firm based in Frankfurt. It has been particularly involved in Mears’ governance in the last year as it successfully led a move to oust long-term chairman Bob Holt (see the people section).

However, the Mears’ board rejected SVM’s attempt to replace him with Andy Hogarth, their preferred pick, saying board appointments should not “be imposed on us by a single shareholder.”

If Mears does face financial difficulties in coming years and is unable to pay out the dividends its shareholders have become accustomed to, expect more disagreements between management and shareholders.

Mears slogan: “making people smile”

Finances

In its last annual report, for 2017, Mears’ work brought in revenues of £900 million. All of that came either directly from the public sector – through local authorities and NHS Trusts or from housing associations. This was slightly down on the previous year but overall Mears has grown quickly. Its revenues more than doubled in size over the previous ten years, increasing from £420 million in 2008.

After all costs were taken off, Mears’ profits were over £20 million each year between 2014 and 2017, and solidly above £10 million in the years before that. Mears will release its results for 2018 in March. In an early announcement to the stock market, CEO David Miles said it had been a year of “very good progress” and that business had been in line with expectations.

Mears is a ‘public limited company’ (PLC), meaning its shares can be bought and sold on the London Stock Exchange. Investors reckon the company’s shares are worth £3.30 each and £363 million when they are all added together (market capitalisation, in the jargon). That puts Mears’ value on a par with companies such as lorry firm Eddie Stobart and Hotel Chocolat.

Consistent profits have allowed Mears to pay millions out in dividends (the jargon for the cash paid out) to its shareholders. Mears paid out £12 million in 2017, up from £11 million the year before. In the five years between 2013-2017, Mears paid out £52 million in dividends, with the amount rising each year.

Mears’ financial health at first glance appears solid. Borrowing too much from banks and other lenders is a major reason why construction and maintenance companies go bust, Carillion most recently. At present Mears does not appear to be close to the same fate.

According to its published accounts, the new activities in its housing and care businesses have not been funded by taking on lots of extra debt. As of 2017, the last year for which full financial results are available, Mears had not increased its levels of borrowing, even with its move into housing development rather than simply maintenance.

Long term debt amounted to £51 million in 2017, down from £60 million the year before, all arranged through credit deals with Barclays and HSBC banks. As of 2017, Mears has the ability to borrow £170 million through those deals if required, plus a new £30 million pot it can access for its new scheme to buy property before selling them onto to long-term developers (see the housing section).

Mears just missed a target for covering its debts in 2018.i But the company said that was mainly due to cash reserves being lower than planned due to being paid for certain activities slightly later than expected.

However, a potential worry for Mears is that its business model depends on winning new maintenance or care contracts every year. Mears makes much of being a high quality and socially responsibly company. If that reputation takes a hit, and local authorities and housing associations are more reluctant to use the company, Mears’ finances would look a lot less secure.

There are already hints to what could happen in Mears’ accounts. Company Watch (no relation to Corporate Watch), a financial analysis firm used by the government, recently described the business models of outsourcing giants Serco, Capita, Interserve and Mitie as “bankrupt”. Mears shares some of the characteristics the analysis pointed to as potential problems.

Like those companies, Mears is operating in ‘low margin’ businesses, facing competition for contracts that, for the most part, do not allow for significant amounts of profit to be made. Mears’ profit ‘margin’ has hovered around 3% for the last ten years, just like the big four outsourcers.

Added to this, Mears – like Serco and the rest – does not own a vast array of ‘tangible assets’ such as buildings, land or equipment that it could sell or rent out in the event it needed to raise cash (but see the housing section, above, for details of Mears’ current attempts to change that).

According to Mears’ 2017 accounts, the value of its long term assets add up to £237 million. Just £22 million of those were tangible assets. Most of the rest, £194 million, were made up of ‘goodwill’. This is a slippery accounting concept that appears when one company buys another for more than the value of its assets at the time of purchase (see a fuller explanation here). The idea is that the acquired companies will in time generate wealth equivalent to the purchase price, so that should be recognised in the accounts. But thanks to amendments to regulations made under the Blair government, companies have been able to use this to artificially inflate their overall worth, with Carillion again the most notorious example (click here for an in depth look at this by the Financial Times).

Goodwill amounts to over 40% of Mears’ total assets – a bigger proportion than Interserve and Mitie, slightly less than Serco and Capita.

Mears’ goodwill comes from their acquisitions of housing and care companies. Without this, the overall worth of the company according to its accounts would drop from £210 million to just £15 million. So can Mears confidently expect the acquired businesses to bring in profits to justify the current valuations?

Almost £100 million of the goodwill is for the home care businesses Mears has bought (see the section on home care above for details). Many home care companies are facing severe financial difficulties, with market leader Allied Healthcare recently at the brink of going under.

Mears’ home care operations only broke even in 2017. Its accounts contain a long justification for the potential of its home care business, and thus maintaining the value of its goodwill. But these all depend on increased local authority funding, which is hard to predict with any confidence.

If Mears does, at some stage, have to accept that it overpaid for its home care businesses, its overall worth could be significantly reduced.

The same applies to the £94 million Mears currently estimates the housing businesses it has bought to be worth (this may have increased significantly with the purchase of Mitie’s housing division in 2018).

Do you have information about Mears you’d like to share with us? Click here to get in touch.

i So-called “net debt”, which financial analysts calculate by subtracting a company’s cash and other easy-to-sell (“liquid”) assets from the total value of the debts it owes to banks, lenders, suppliers and other third parties