The National Wealth Service: Players and Scandals

This is the second in a series of three articles investigating the accelerated privatisation of our NHS for private healthcare profits. Part one detailed our data research into five companies reaping profit from NHS contracts. The third article is a timeline detailing NHS privatisation since its formation in 1948.

Relentless years of cuts and privatisation efforts have pushed the NHS to the brink of collapse. Yet, little data exists on the true extent to which private healthcare providers have profited from successive governments slicing up and selling off the UK’s National Health Service.

To help address that gap, Corporate Watch’s latest investigation has revealed how healthcare profiteers Bridgepoint, Bupa, Centene Corporation, Spire Healthcare and UnitedHealth Group (UHG) made £4.6bn from public health contracts going back to 2013, in addition to a share of further tenders worth an eye-watering £61.87bn. And these figures relate to just five firms, among hundreds of others, who’ve raked it in through NHS deals over the years.

Digging into these companies, and the people behind them, we uncovered a murky history of scandals and regulatory violations, as well as a rogue’s list of public officials and politically connected figures on their boards and among their shareholders. This all poses serious questions about the UK government’s decision to entrust these firms with the provision of public health services.

Collaborating with Good Jobs First, which maintains databases tracking regulatory violations and penalties in the US and the UK, our findings show:

- Some of these firms’ senior officers in fact migrated to these companies from government posts or positions of influence within the NHS, and vice-versa.

- Their boards of directors and shareholders feature a vibrant cast of powerful UK political figures, including government ministers and senior members of the House of Lords.

- These groups have received fines totalling at least £2.2 billion for a litany of offences and infractions, ranging from massive financial frauds and anti-competitive practices to gross violations of patient and worker care and safety regulations, some of which pertained to serious abuses and even deaths at work and in care.

Drivers of the privatisation agenda

In December 2022, the Conservative government announced its post-pandemic Elective Recovery Taskforce, designed to “turbo-charge” the provision of public health services through private providers. It’s little surprise that people like David Hare and Jim Easton had seats at the table with Rishi Sunak at the launch.

As chief executive of lobbying group Independent Healthcare Providers Network, it’s Hare’s job to represent the interests of firms including Bupa, Circle Health Group (owned by Centene), Care UK (owned by Bridgepoint) and Optum (UHG’s UK subsidiary) in Westminster. He was awarded an MBE in early 2023 for his “invaluable contribution to the pandemic response,” a role that fast tracked treating millions of NHS patients through private providers.

Easton, meanwhile, has previously held several NHS positions, including chief executive of York Hospital’s NHS Foundation Trust and National Director of Transformation for NHS England. Whilst there, he oversaw the development of government “efficiency savings” programmes to slash more than £20bn from services. He also awarded at least 12 NHS 111 contracts to Harmoni, a complex care firm purchased by Care UK in 2012 just months after Easton joined the group, where he now acts as CEO of spin-off provider Practice Plus.

Other attendees brought a wealth of capitalist expertise gained in other sectors. Paolo Pieri, CEO of Circle, started out as an accountant in Glasgow before moving to Silicon Valley in the 1990s to work with tech start-ups. He later became CFO at Virgin Megastores and lastminute.com. Meanwhile, Justin Ash, who heads up Spire Healthcare formerly acted as managing director at Lloyds’ Pharmacy. His earlier ventures included stints as a commercial director at Allied Domecq Spirits & Wines and general manager of KFC’s operations in the UK and Ireland.

Whatever their credentials, it’s no surprise that these people are all well-connected politically. Some of their companies’ notable links to powerful players in Westminster include:

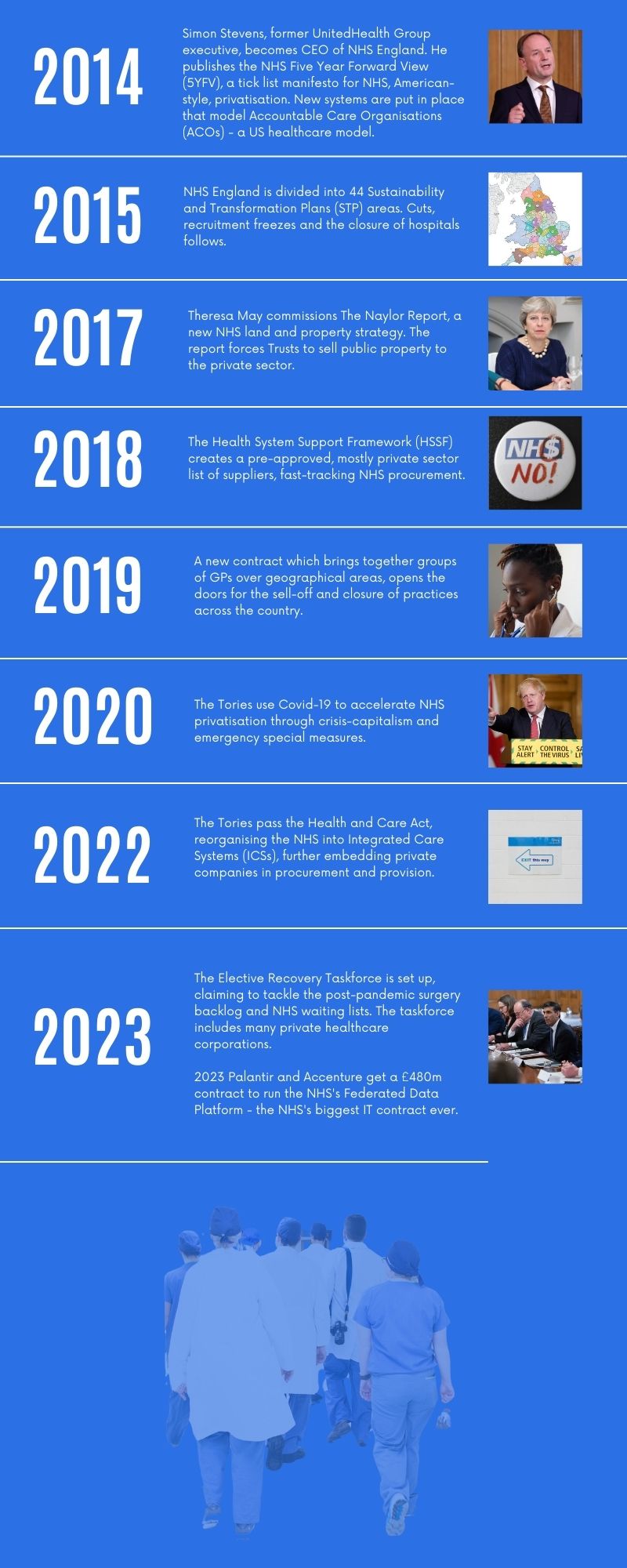

- UHG’s former head, Simon Stevens, was appointed as chief executive of NHS England by the government in 2014 after authoring the Five Year Forward View (5YFV), the Tory blueprint for carving up the NHS for profit. He’s now a member of the House of Lords.

- The wife of Tory health minister Neil O’Brien currently acts as GP engagement lead for Circle, while former Conservative MP Mark Simmonds has previously worked as a strategic adviser at the firm. In 2012, Simmonds was forced to apologise to parliament for failing to mention his interests when speaking in support of the Health and Social Care Bill, which helped accelerate privatisation of the NHS.

- John Nash, co-founder of Care UK, and his wife are reported to have donated over £300,000 to the Conservative Party, including more than £21,000 that went directly to the office of Andrew Lansley during his time as health secretary. Nash was also one of George Osbourne’s key advisers in developing Tory austerity plans, for which he earned a peerage in 2013, and he continues to hold shares in Care UK today as Baron Nash of Ewelme.

- At least 14 other members of the House of Lords have at various times declared interests in Circle, Spire, Bupa and/or Optum. Some of these figures have also faced criticism in the past for their interests and track records in a variety of other sectors. Take Lord Glendonbrook, who alongside his historic interests in Spire and UnitedHealth has considerable holdings in Big Oil and the arms industry, and who was awarded his peerage in 2011 after donating more than £1m to the Conservative Party. Or Lord Green of Hurstpierpoint, who along with his shares in Optum served as head of HSBC between 2005 and 2010 – the same period the bank was later revealed to have laundered money for the Taliban and the Sinaloa Cartel.

Sunak’s executives are generously compensated for their roles heading up some of the UK’s largest private healthcare providers. In 2020 Julian Ash, for instance, earned himself roughly £1.2 million – including a tidy bonus and other benefits worth £600,000 on top of his base salary – after the pandemic saw Spire benefit from NHS contracts worth more than £350m. And while neither company has provided a detailed breakdown of director remuneration in their annual accounts, Circle paid its board a total of £3.1m in 2021, with Practice Plus doling out a combined £1.16m to its top executives the following year.

Despite hefty remuneration for these UK executives, profit from NHS contracts ultimately feeds back into ever higher payouts for CEOs and directors of the parent companies. For example, Centene Corporation and UHG doled out a combined total of $134m (£106m) to their top 13 officers in 2022 alone – equivalent to the combined average annual salary of about 3,000 NHS workers.

Fraud and consumer protection violations

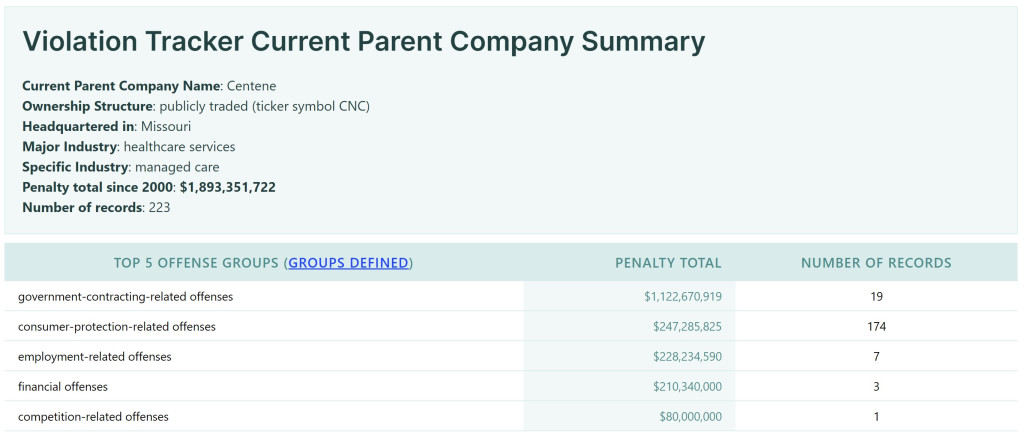

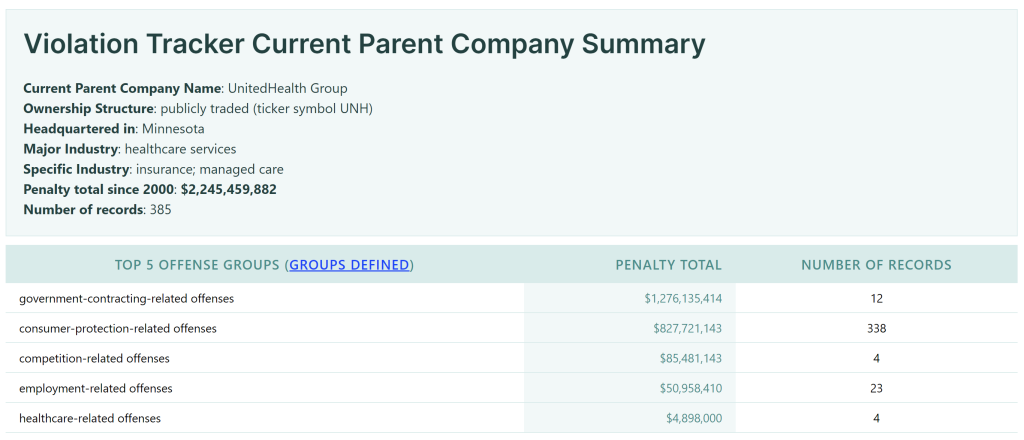

Data compiled by Good Jobs First under their Violation Tracker initiative reveals truly alarming patterns of financial misconduct among these companies, which are now deeply entrenched in the NHS. In particular, corporate giants Centene and UHG have faced hefty penalties for defrauding patients and public healthcare systems in the United States, where both are based.

Centene has been fined over $1.8bn (£1.4bn) for a string of infringements with over $1bn (£790m) of that total coming from 18 government contracting-related offences. The company remains at the heart of an at least $1.3bn (£1bn) billing-fraud furore, having already paid out to the US Department of Veterans Affairs and several state governments to resolve allegations of overcharging for Medicare, a government health insurance program, through duplicated or inflated claims. In terms of number of cases, however, most of Centene’s US violations in fact relate to continued abuses of consumer protection regulations, which have seen them fined $247m (£196m).

Total value of US fines received by Centene via Violation Tracker

Total value of US fines received by UHG via Violation Tracker

UHG’s track record tells much the same story, with historic fines against the healthcare giant of over $1bn (£790m) for consumer protection and government contracting offences. In 2011, for instance, the group was accused of defrauding Medicare to the tune of “hundreds of millions and likely billions of dollars”, after spending roughly $7.22m (£5.7m) on lobbying around the period in which the Affordable Care Act, which dramatically expanded the state-backed programme as part of an attempt to reform healthcare insurance in the US, was still under debate by Congress.

There’s also evidence of dubious financial practices taking place in the UK among the corporate entities Corporate Watch targeted as part of this investigation. Advocates for a more transparent financial system, such as Tax Research UK, have taken aim at Care UK, Circle, Spire and Optum for using offshore jurisdictions to reduce their UK corporate tax liabilities.

Abuses and deaths among patients and workers

Perhaps the most egregious scandal to have engulfed any of the UK companies featured in this report was the case of Ian Paterson, dubbed the ‘butcher surgeon’. Paterson, a former breast surgeon, is currently serving a 20-year sentence for performing unnecessary or unapproved procedures on more than 1,000 cancer patients at Bupa and Spire hospitals in the West Midlands, with a further 1,500 victims discovered on an old IT database in February 2023.

After his conviction in April 2017, Spire released a statement saying “what Mr Paterson did in our hospitals […] absolutely should not have happened” and expressing “how truly sorry we are,” only to then sue the NHS four months later for allegedly failing to warn them over his conduct. That action came just weeks after the firm was sued by hundreds of Paterson’s patients, who claimed Spire had allowed the surgeon to continue work well after his 2012 suspension by the General Medical Council.

Spire isn’t alone in coming under fire for the quality of management and services at its facilities. Care UK has also been repeatedly slammed for cost-cutting at the expense of both staff and patient welfare. Journalistic investigations have uncovered multiple cases of alleged neglect at their care homes, such as a 2011 administrative blunder that saw an 85-year-old dementia patient left unattended in bed for three days (her carers mistakenly believed she was receiving treatment at hospital). Similar criticism has been levelled at Bupa, with their UK care facilities variously described over the years as “disgraceful”, riddled with “systemic failings”, and sources of “serious concern”. One home was censured as a place where “human rights were not protected” before being shut down, while a staff member at another was quoted as saying “I would hate it if my mother was in here.” In Australia, the 2019 death of an elderly cancer patient, admitted to hospital with maggots crawling in an open and fungated ear wound, also saw Bupa’s CEO forced to “unreservedly” apologise for “totally unacceptable” shortcomings in its aged care network.

Bupa Care Homes: A Gross Litany of Scandals

Over the past decade there have been a string of failures, patient abuse scandals and deaths in Bupa care homes. Here are some of the worst in the UK, uncovered through research by Good Jobs First’s Violation Tracker UK:

2013: 'Horrific abuse' exposed at Beacon Edge care home that led to the prosecution of Bupa staff.

2013: A patient with dementia found dead next to her bed at Beacon Edge, resulting in an HSE investigation and Bupa’s prosecution in 2016.

2015: The Care Quality Commission (CQC) fined Bupa £4,000 after inspections of Broadoak Manor Nursing Home found residents were still at risk due to its repeated failure to maintain national care and welfare standards.

2015: A resident died after they contracted legionnaire's disease from poorly maintained facilities. Bupa were fined £1.6m after an investigation by the HSE.

2015: An elderly resident at West Riding Residential Home endured prolonged suffering before her death in 2016 arising from multiple falls due to care failures. The CQC prosecuted Bupa and it had to pay £123,700 in fines and costs.

2016: Bupa were ordered to pay a fine and costs exceeding £1m, a record for fire safety breaches in the UK, after a vulnerable resident burned to death in fire.

2017: Relatives of two women who died at a Bupa care home in central London nursing home accused Bupa of failing to administer pain relief to ease end-of-life suffering

2017: Bupa’s Crawfords Walk specialist dementia care home was rated inadequate by the CQC in response to ‘institutional abuse’ being exposed in a Channel 4 Dispatches documentary. The CQC also considered enforcement action, subject to legal proceedings.

2021: An eight year old girl suffered ‘catastrophic injuries’ after being crushed by a falling tree outside a Bupa care home. Bupa were fined over £400,000 following an HSE investigation into safety failures.

2022: A ‘gross failure’ of neglect at Bupa’s Highgate Care Home resulted in a resident choking to death after being fed undercooked cauliflower.

Nor is it only patients who find themselves exposed to dire and life-threatening conditions. Circle Health has faced fines of £160k for exposing employees to potentially deadly chlorine gas, while BMI Healthcare, which was later acquired by Circle, was previously ordered to pay £450k for breaches of the UK Health and Safety Work Act that led to the tragic death by electrocution of one of its workers.

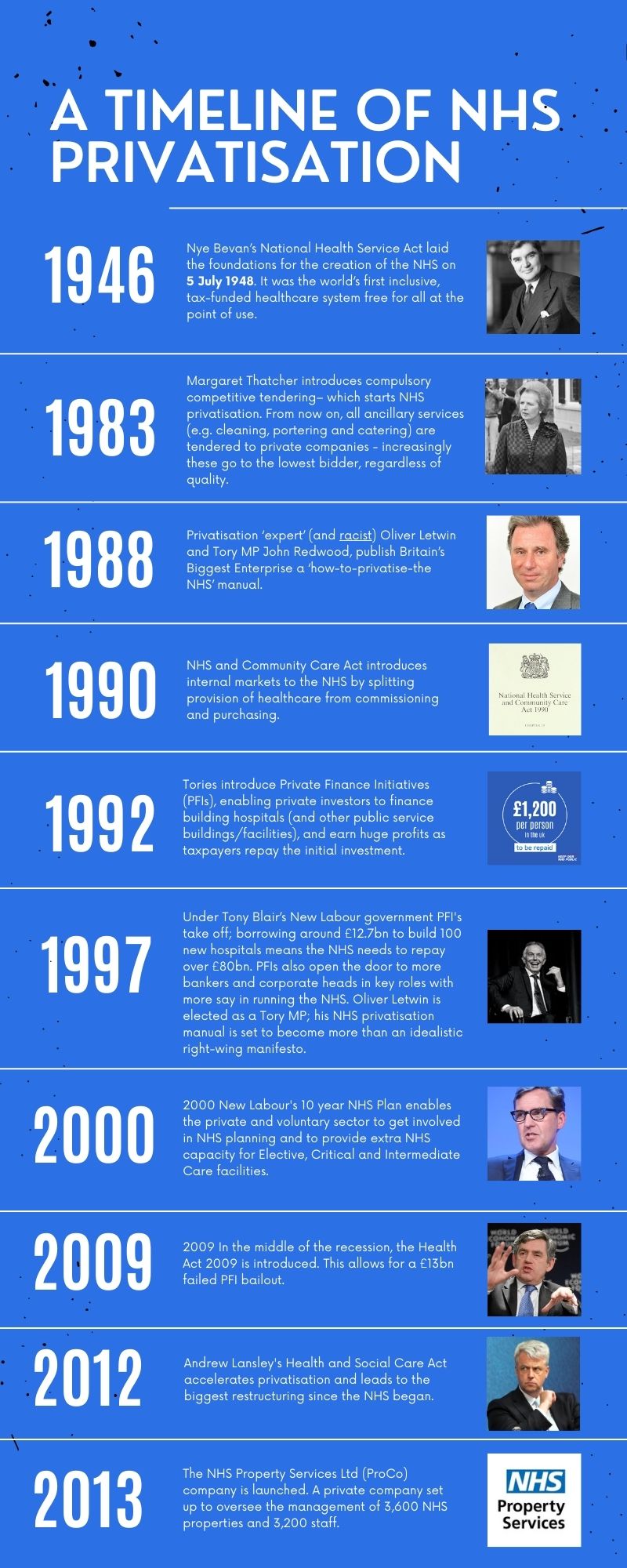

Timeline of betrayal

Although privatisation has gone into overdrive under the current government, successive Tory and Labour governments have been dismantling our NHS for years. Legislation, continual restructuring and policies have made way for global giants and their overpaid bureaucrats to muscle in on our unique healthcare system.

Part three covers the descent in more detail, but here are some key steps of that journey:

Foxes in the hen house

Corporate Watch has revealed how over the past decade, Bridgepoint, Bupa, Centene, Spire and UHG bagged NHS contracts worth tens of billions of pounds. It’s these companies, with their revolving door of corporate and political interests, and many others just like them, to which Rishi Sunak’s government has entrusted the future of our NHS. Our research raises serious questions about the suitability of private companies, like the five we examined, operating public health and social care services in this country.

It’s on the record that some firms have defrauded the US healthcare system. Several have repeatedly violated worker safety standards, resulting in tragic and avoidable deaths. Others, meanwhile, failed to provide even the most basic level of care to some of their most vulnerable patients – abandoning them, quite literally, to rot in their beds. Yet despite this, the government’s priorities align with these companies and their lobbyists whose enduring influence is apparent in the implementation of US-style Integrated Care Boards (ICB) and post-pandemic plans for the NHS. They are represented on the government’s Elective Recovery Taskforce, their priorities apparent in recommendations to utilise the private sector to clear the backlog of patients awaiting treatment in an NHS system already broken by years of underfunding. All this comes amidst increased drive for corporate profit; a drive which is killing people and our NHS.