The National Wealth Service: NHS Privatisation Timeline

This is the third in a series of three articles investigating the accelerated privatisation of our NHS for private healthcare profits. The first detailed our data research into five companies reaping profit from NHS contracts. Part two examines the litany of scandals and the key players in the five companies we researched.

Spiralling waiting times, an exhausted, disillusioned workforce and rising numbers of people unable to access basic services: our NHS is broken.

Although cracks in the system became impossible to ignore during the coalition-led years of brutal austerity policies, dismantling the NHS for profit has been in motion for years. Successive Tory and Labour government policies have pushed through healthcare legislation and restructuring programmes that have given increasing amounts of money and power to private companies for decades. Of course, those on the frontline have been sounding warning bells for years, but it took a global pandemic for many people to start to recognise the extent of healthcare privatisation, and the implications of this.

This timeline documents the most significant points of ideological, legislative and policy shifts.

The road to ruin

1946 – Nye Bevan’s National Health Service Act laid foundations for the creation of the NHS on 5 July 1948. It was the world’s first inclusive, tax-funded healthcare system free for all at the point of use.

1956 – Guillebaud Report. Since its inception, Tories had tried to challenge the NHS and led an inquiry to investigate costs. The findings revealed that the NHS was underfunded and highly cost-effective.

1979 – Margaret Thatcher elected on a right-wing ‘monetarism’ manifesto. This saw the principles of neoliberalism firmly entrenched: increased privatisation with taxes driven lower for corporations and the wealthy. Thatcher’s government made no secret of its wish to cut public services and decimate the welfare system.

1983 – When Thatcher introduced compulsory competitive tendering the move towards NHS privatisation started in earnest and has continued for the next forty years. Ancillary services – such as cleaning, portering and catering facilities – could now be tendered to private companies. These tenders increasingly went to the lowest bidder, regardless of quality, and it’s now widely accepted that this led to the emergence of MRSA in hospitals. NHS provision was reduced for dentists and opticians and charges started to creep in for these services.

1983 – When Thatcher introduced compulsory competitive tendering the move towards NHS privatisation started in earnest and has continued for the next forty years. Ancillary services – such as cleaning, portering and catering facilities – could now be tendered to private companies. These tenders increasingly went to the lowest bidder, regardless of quality, and it’s now widely accepted that this led to the emergence of MRSA in hospitals. NHS provision was reduced for dentists and opticians and charges started to creep in for these services.

Roy Griffiths’ – then director of Sainsbury’s – Griffiths Report recommended changes to NHS management structure and opened up recruitment to administrators from the private sector which cemented the idea of our healthcare system as a business. By 1995, there were 26,000 senior NHS managers – up from 1,000 in 1985 – and administrative spending more than doubled.

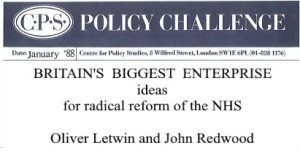

1988 – Concrete moves started (proposed in the Griffiths Report) to shift care for the elderly from the NHS (which provided free care) to local government meaning it would now be means tested. This entrenched the privatisation agenda even further and opened up continued financial attacks on local government spending. Meanwhile, privatisation ‘expert’ and racist Oliver Letwin and Tory MP John Redwood, published Britain’s Biggest Enterprise a ‘how-to-privatise-the NHS’ manual. It proposed that reform “should include as a minimum”:

- Establishment of the NHS as an independent trust.

- Increased use of joint ventures between the NHS and the private sector.

- Extending the principle of charging.

- A system of ‘health credits’.

- A national health insurance scheme.

In the same year, right-wing think tank the Adam Smith Institute (ASI) published similar ideas in The Health of Nations. This proposed dismantling the NHS through a shift to US-style healthcare structures. It identified the risk of opposition from NHS workers and the public in the push for increased privatisation.

1990 – The NHS and Community Care Act forced the NHS into the formation of 57 Trusts. Although ‘sold’ as giving greater freedom towards self-governing NHS areas, these actually pushed back door privatisation initiatives further forward under what was known as the ‘internal market’ policy. Trusts introduced internal NHS markets by splitting the provision of actually providing healthcare from the ability to purchase essential materials (e.g. drugs and equipment) and commission out other services. Because Trusts could generate income and raise their own revenue, managers increasingly started to focus on charging for private care, at the cost of both NHS patients and staff. With the formation of NHS trusts, management structures increased; with more people coming from corporate entities.

1992 – Tories introduced Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs), enabling private investors to finance building hospitals (and other public service buildings/facilities). Under this model, investors could earn huge profits as taxpayers repaid the initial investment through an annual fee or leasing the development back to the government. However, it was the next government that would fully run with this agenda.

1997 – Tony Blair’s New Labour elected to government entrenching Thatcher’s neoliberal policies even further. It funded “100 new NHS hospitals with PFIs” by borrowing around £12.7bn. The true cost of this ‘investment’ was expected to exceed £80bn by 2019, with subsequent rises in inflation hiking it even further. Under PFI government becomes the purchaser of services, not assets. These so-called ‘design, build, finance and operate’ initiatives meant private companies now owned the hospitals, schools and roads ultimately paid for with public money. PFIs opened the door to more bankers and corporate heads with positions of power, and therefore more say in running the NHS. PFI debts continued to soar and eventually, the NHS had little choice but to sell off land – one of its most valuable assets.

Oliver Letwin was elected as a Tory MP. Now, his NHS privatisation manual was set to become more than an idealistic right-wing manifesto.

2000 – New Labour introduced its 10-year NHS Plan. Health secretary Alan Milburn signed a ‘concordat’ with the private sector which enabled it to provide extra NHS capacity for elective, critical and intermediate care facilities. This meant NHS patients in England could be seen by the private and voluntary healthcare sector. These contracts were far more expensive than equivalent NHS provision. In addition, the concordat invited private and voluntary healthcare sectors into local and national NHS planning. PFIs moved to a new funding model which saw them taking huge loans at high interest rates to the detriment of the public purse.

2004 – The first Foundation Trusts (FTs) were granted licenses. FTs had less government oversight and control, less public accountability, were more commercial and further opened up the NHS for back-door privatisation. Private and voluntary health sectors could apply to become an FT, meaning that corporate interests become eligible to win contracts to run public healthcare services.

Health secretary, John Reid extended the commitments of the NHS Plan to include ‘patient choice’ – which included the possibility of publicly funded treatment in private hospitals. This NHS improvement plan intended the private sector to provide up to 15% of NHS services by 2008.

New Labour introduced payment by results. Providers would now get paid per-patient treatment instead of getting funding in block contracts. This gave the private sector the option to cherry-pick more ‘profitable’ and less complex treatments.

The Alternative Provider Medical Services (APMS) were introduced, allowing primary care contracts to go to the private and charity sectors. This enabled private GP companies to operate multiple surgeries, which US healthcare firms (such as United Health Group and Centene) would step in and buy.

2008 – The Transforming Community Services programme was established, setting in motion the separation of commissioning from the provision of community services. This introduced a competitive model in providing community services meaning ‘any willing provider’ could bid for contracts. Companies like Virgin Care stepped in to profit from community hospitals. This is now widely seen to be a failure for NHS, patients and staff.

2009 – In the middle of the recession, amid massive funding cuts for the NHS and bank bailouts, Gordon Brown oversaw the Health Act 2009. This effectively allowed for the bailout of failed PFI schemes to the amount of £13bn that year. Serious questions emerge about the financial viability of PFI hospitals.

2012 – Andrew Lansley’s Health and Social Care Act accelerated privatisation leading to the biggest restructure since the NHS began. 207 Clinical Commissioning Groups(CCGs) were established across England and put in charge of commissioning and competitive tendering of all large NHS contracts. This process enforced competition between the NHS, private and voluntary sectors. It removed the health minister’s legal duty to provide healthcare for all. The NHS Commissioning Board (later NHS England) took responsibility for this, making the government less accountable overall. The amount that NHS Foundation Trusts could earn from private patients was drastically increased, as were administration costs. The Act instigated an immediate and massive increase in the private sector winning contracts.

2013 – The NHS Property Services Ltd (ProCo) company launched. A private company set up to oversee the management of 3,600 NHS properties and 3,200 staff.

Commissioning Support Units (CSUs) were set up as part of the 2012 Acts’ reorganisation. NHS-approved private companies started offering business, healthcare, procurement and commissioning support and intelligence to CCGs. Notorious companies such as Capita and Optum were approved to become CSUs and NHS marketisation pushed forward even more.

2014 – Simon Stevens became CEO of NHS England. Stevens had been laying the foundations for NHS privatisation for years not only in his former government roles but also as a senior executive for the (then) largest American health insurance company, UnitedHealth (UH) Group. While there, his remit included lobbying for the NHS to join the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) potentially opening It up for US deals. Stevens’ career, both in UK government and during his time at UH, was dominated by scandal and ruthlessly corporate-driven.

Stevens was the driving force behind publishing the NHS Five Year Forward View (5YFV) which is a tick-list manifesto for NHS privatisation. Thinly disguised as a plan for NHS ‘transformation’ 5YFV is actually a model to fully embed an American style of healthcare privatisation. As part of the ‘transformation’ came the introduction of new systems for structuring care in England. These were precursors of Accountable Care Organisations (ACOs) – a US healthcare model.

2015 – England was divided into 44 geographical areas (‘Footprints’) designed to implement the five-year plan through local Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STP). They were collectively responsible for the health and care £22bn ‘efficiency savings’ laid out in the 5YFV. This led to cuts, recruitment freezes, the closure of hospitals and the private sector taking more NHS contracts.

STPs advocated the integration of health (NHS) and social care, which further embedded existing problems. The NHS, free at the point of use, is not means tested. But social care is means tested. Since the Tory coalition came to power, austerity policies delivered huge cuts to local government alongside significant cuts to social care funding which left the system in crisis.

2017 – Theresa May’s government commissioned a report by scandal-ridden accounting and consultancy firm Deloitte. The Naylor Report was a new NHS land and property strategy. The report forced Trusts to sell public property to the private sector to make the savings called for in the 5YFV.

2017-2018 – The 44 STP ‘Footprint’ areas morphed into Sustainable and Transformation Partnerships, which then mutated into Accountable Care Systems (ACSs). These were set to change into more complex ACOs over time. But the government decided to distance itself, in name only, from the increasingly controversial ACOs and instead started talking in terms of ‘Integrated Care Organisations’.

2018 – The Health System Support Framework (HSSF) was established. This brought pre-approved, accredited suppliers together who could now fast-track NHS procurement. The suppliers list read like a ‘who’s who’ of healthcare corporations.

2019 – The Long Term Plan (LTP) published, announcing that 44 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) would evolve from the STPs and replace CCGs as the funding and commissioning bodies across England by 2021. It was yet another plan that failed to address some of the biggest issues facing the NHS and set another major restructure in motion. ICSs are ACOs by another name.

A new contract brought groups of GPs together over geographical areas. This opened the doors for the sell-off and closure of practices across the country. It also led to private developers building new, merged, all-purpose health centres and private companies going for integrated health data contracts.

2020 – The Tories used Covid-19 to accelerate NHS privatisation through crisis capitalism and emergency special measures. The pandemic deepened the impacts of austerity and NHS privatisation on the population. Massive contracts were handed to private companies, such as Capita, Palantir and Serco, without the usual legal processes or oversight. Test & Trace, PPE contracts, the buying up of private beds, and the management of Covid data all formed part of these deals. Many of these contracts were total failures as we witnessed 1000s of avoidable deaths. The UK recorded one of the highest Covid-19 death rates in the world.

Billions of pounds in PPE contracts went to Tory donors and friends while frontline NHS staff and their families died because of a lack of appropriate PPE. The government propped up the private sector during the pandemic through public money and massive borrowing.

2022 – Government passed the Health and Care Act. As previous Corporate Watch research highlighted, the legislation ‘re-organised’ the NHS into Integrated Care Systems (ICS). In theory, these give patients easier access to a range of services in their community: merging health, mental health, social care etc. But critics warned that the true remit of ICS was to destroy public capacity to provide NHS services by embedding private companies in their procurement and provision. Over 200 companies are now accredited with NHS England, with many lined up to support ICS dealing with data and digital systems and an array of US-owned giants on the list.

Each ICS has an Integrated Care Board (ICB), a statutory NHS board that manages the health budget, develops a health plan, and arranges provision for the population it serves. Members of the private sector are allowed to sit on this board. The ICB works in partnership with other private and state agencies under the umbrella of Integrated Care Partnerships (ICPs). The private sector is involved in managing budgets and creating strategy for the NHS.

2023 – Tories set up the Elective Recovery Taskforce, claiming it will tackle the increasing surgery backlog and NHS waiting lists. This taskforce includes many private healthcare corporations. So-called elective surgery is non-urgent surgery. It’s here that NHS waiting lists are soaring. Yet, during the pandemic, private hospitals carried out 45% less NHS-funded elective care than in the previous year—the very thing they were supposedly paid to do.

Spy-tech firm Palantir and Accenture secure a £480m contract to run the NHS’s Federated Data Platform (FDP) for the next five years at least – the NHS’s biggest IT contract ever. This creates an NHS software system that spans Trusts and ICSs across the country.

Life support

Most people are familiar with the terms NHS ‘backdoor privatisation’ or ‘privatisation by stealth’. Given the astronomical sums now going to private healthcare giants, and the implications of the current government’s Elective Recovery Taskforce, it seems clearer by the day that the profiteers have abandoned any pretence of using the backdoor to mop up NHS profit. They’ve been invited through the front door by the government, and all illusion of stealth is gone. Even a change of government offers little hope of booting the corporates out since Kier Starmer’s Labour openly supports privatisation.

The biggest, indeed only, challenges are coming from campaign groups and NHS workers. So now, more than ever, they need our solidarity and for us to share information far and wide about the true impact of privatisation and profiteering. Through collective action, it’s time to get our NHS off life support and back to health for us all.

Images via: Wikimedia Commons, NARA, Wikimedia Commons, No 10 Flikr, No 10 Flikr, No 10 Flikr