Ownership and subsidiaries

This post is part of Investigating Companies: A Do-It-Yourself Handbook. Read, download or purchase the whole book here.

[responsivevoice_button]

The fundamentals of company ownership are relatively easy to understand: whoever owns the shares in the company owns the company. But shareholders can be companies as well as people. If one company buys another for example, the buyer may simply run the company it has acquired as its owner and shareholder, rather than changing the direct ownership of all its possessions and operations.

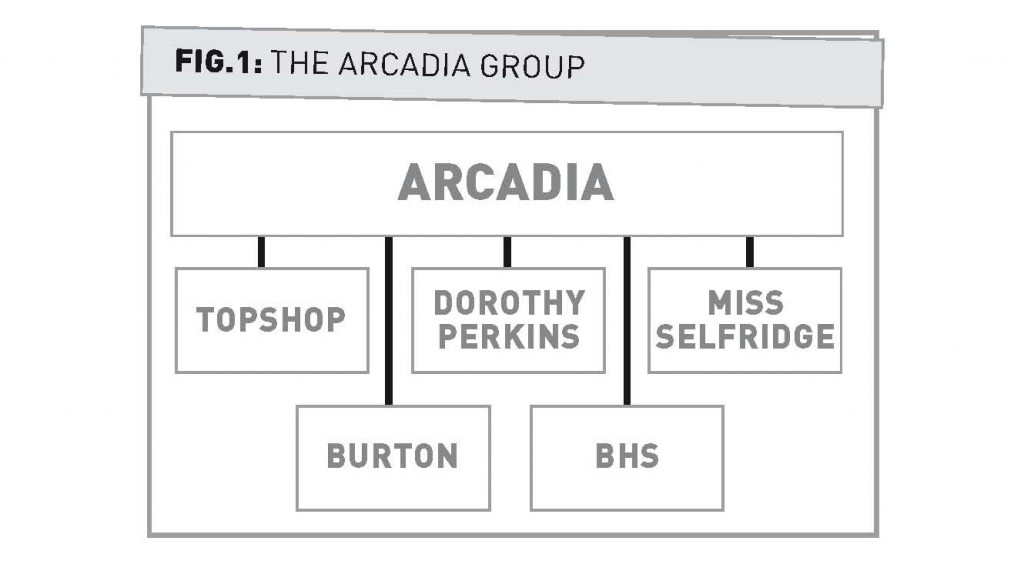

When the retailing company Arcadia bought British Home Stores (BHS) in 2010 for example, it kept BHS going as a separate company that it owned all the shares of, rather than changing the direct ownership of all the possessions and operations. As Figure 1 shows, Arcadia also runs TopShop, Dorothy Perkins, Miss Selfridge, and Burton, among others, as subsidiary companies.

The directors of a company may also decide to create subsidiaries to take care of certain parts of its everyday operations.

If they go to do business in a new country, they may set up a subsidiary that is registered in that country, with its own offices and staff. Marks and Spencer (Ireland) Limited, Marks and Spencer Czech Republic and Marks and Spencer (Asia Pacific) Limited are M&S subsidiaries selling its products in Ireland, Czech Republic and Hong Kong respectively, for example.

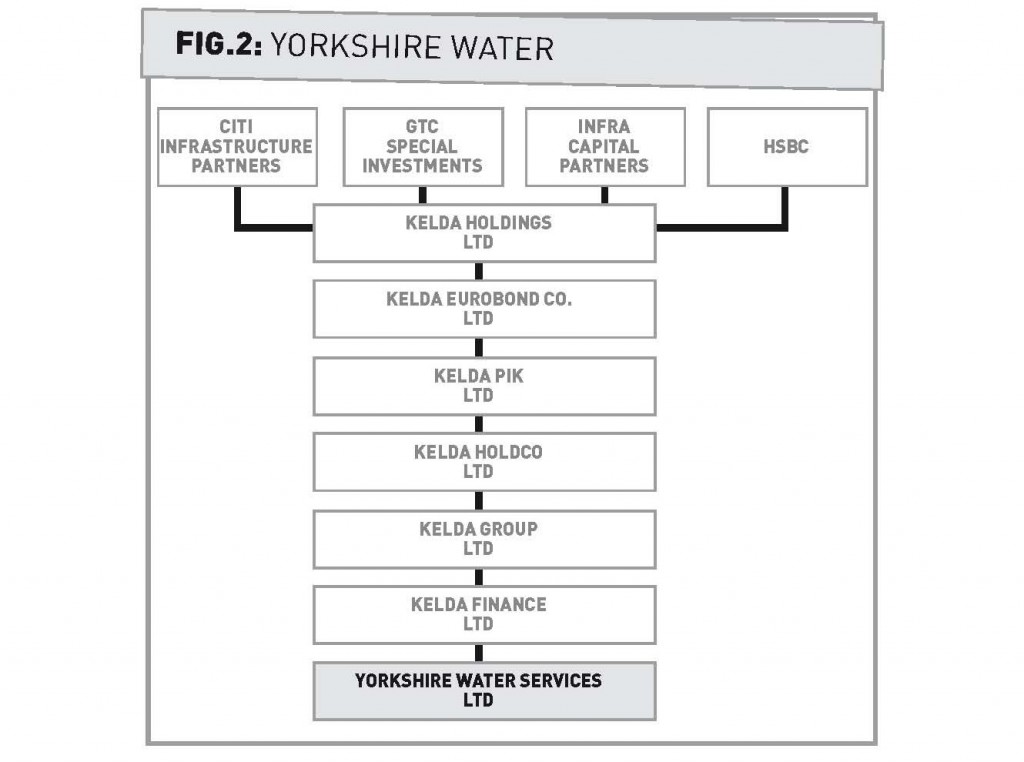

Sometimes, you’ll find there’s a chain of subsidiary companies. Have a look at the structure of the Yorkshire Water group (see figure 2). The ‘operating’ company – i.e. the one that hires the staff and owns the pipes that make water come out of Yorkshire taps – is Yorkshire Water Services Limited.

Its ultimate owners – HSBC bank and British, American and Singaporean investment funds – own it through a string of companies, which each own the shares of the company ‘below’ them in the chain. They each perform various financial or administrative functions, which, for legal or accounting reasons, the Yorkshire Water directors and accountants have decided it is best to do through a separate company. Companies like this are known as ‘non-operating’ companies as they don’t actually produce or sell anything themselves. They are all run from the same office, share directors and employ few – if any – staff.

As a rule, the bigger the company, the more subsidiaries it will have. Marks and Spencer and the Arcadia group both have more than fifty, for example. Some of these may serve certain questionable purposes. Arcadia is owned through Jersey-registered companies by Cristina Green, the wife of Arcadia CEO Philip Green, and a resident of income-tax free Monaco, which helps keep the family’s tax bills down. But most will probably just be playing some kind of administrative purpose. Be aware of the various subsidiaries but don’t worry about understanding exactly why they’ve all been set up – chances are only a few of the company’s accountants really know what they’re all there for.

And don’t be surprised to find companies listed as ‘dormant’, or that don’t appear to do anything at all. They may have long ago performed whatever function they were originally set up for but it takes much more effort to eradicate a company than it does to create one.

In general, you can treat companies as if they are a single entity when they are all owned and controlled from the same source, and treat the owner as responsible for the actions of all the companies in the ownership chain (see section 2.6 for finding out the effect of the subsidiaries on a company’s accounts).

As we saw with the Yorkshire Water example, many companies exist to make money from buying and selling the shares of other companies. Many of the largest shareholders in big companies are so-called institutional investors – banks, pensions and investment funds that pool people’s money together.

This is especially true of publicly-quoted companies. Look at the list of Facebook’s ten biggest shareholders as of the end of 2012:

1. Mark Zuckerberg 64.97%

2. Duston Moskovitz 8.30%

3. Eduardo Saverin 6.30%

4. FMR LLC via its funds 3.23%

5. Vanguard Group Inc via its funds 2.39%

6. Blackrock Inc, via its funds 1.81%

7. T Rowe Price Group Inc, via its funds 1.75%

8. Valiant Capital Management LP, via its funds 1.61%

9. Elevation Partners LP 1.50%

Invesco Ltd, via its funds 1.48%

Mark Zuckerberg has kept hold of 65% of the shares, and two other co-founders of the website are the next two biggest shareholders. But after them it’s all investment funds.

Facebook is relatively new, and the longer companies shares are bought and sold, the more diversified their ownership tends to get. Take the shareholders of notorious outsourcing company G4S for the same date:

1. Invesco Ltd 16.04%

2. Prudential Plc via its funds 6.33%

3. Cevian Capital II GP Ltd 5.11%

4. Vidacos Nominees Ltd 5.11%

5. Affiliated Managers Group Inc via its funds 5.08%

6. Tweedy, Browne Global Value Fund 5.06%

7. M&G Investment Funds (1) 5.04%

8. BPCE SA via its funds 4.98%

9. Harris Associates LP 4.93%

10. Blackrock Inc via its funds 4.72%

All of its biggest shareholders are investment funds – who will each be managing the money of thousands of individuals. Often the people whose money the funds are investing don’t know where it is going. Further down the list of G4S shareholders, for example, are the pension funds of public-sector workers from West Yorkshire and Wisconsin. Many of them were surprised to learn, when told by campaigners protesting against G4S, that their pensions were invested in a company accused of manslaughter, mistreating their workers and cost-cutting in the public services they had taken over.

See section 3.1 for how to find out who a company’s shareholders are.

FUNDS AND VOTING: When institutional investors own shares in a company they have voting rights, just like normal shareholders. However, it is usually the people who manage these funds that exercise the voting rights, not the people whose money is in the fund.

FRANCHISING: When one company or individual uses the business model and brand of another, it is operating as a franchise. Many McDonald’s stores, for example, are run by individuals, who pay a royalty fee for using the McDonald’s brand and management fees to the McDonald’s corporation.