Rough-sleeper raids: how homeless charity deportations carry on rebranded

by Eve Dickson and Benjamin Morgan

In December 2017 the High Court ruled the Home Office’s policy of detaining and deporting EU rough sleepers unlawful. The Gureckis judgment, named after a rough sleeper affected by the policy, was the result of more than a year of research, litigation and campaigning by the Public Interest Law Centre (PILC) and activists from North East London Migrant Action (NELMA).

Earlier that year, a Corporate Watch report had exposed how local councils and homelessness charities were collaborating with the Home Office to arrest, detain and deport European nationals found sleeping rough in London. [1]

As it becomes clear that the border regime has made it impossible for the government to ’bring in’ all rough sleepers during the corona crisis, evidence published here for the first time suggests that the government, still working with its charity and council ‘partners’, is developing new and subtler strategies to remove homeless migrants from the UK.

This report, based on leaked documents and Freedom of Information disclosures, reveals that local authorities and charities are continuing to collaborate with the Home Office to enforce immigration controls.

The Fallout

Since 2017 many of the actors involved in rounding up rough sleepers have distanced themselves, in public at least, from policies that involve locking up or deporting homeless people. Openly attacking ‘vulnerable’ migrants has become less palatable after the Windrush scandal and the success of activists in highlighting the effects of the ‘hostile environment’.

But the bureaucratic and commercial drive to make rough sleepers disappear has not abated. Rather, a period of retrenchment has given way to renewed enforcement efforts.

St. Mungo’s

St. Mungo’s reputation—and fundraising—took a hit after their involvement in deportations was revealed. In November 2019, after previously denying its true role in immigration raids, the charity published the findings of an internal review into its collaboration with Immigration Compliance and Enforcement (ICE) teams between 2010 and 2017.

Buried in the review are a number of grudging admissions: that the charity shared information without consent; that rough sleepers were detained and deported as a result; and that St. Mungo’s misled campaigners about information sharing with the Home Office.

The review reveals that until 2016 working with ICE teams ‘was considered to be good practice in the sector [if] other efforts to engage the individual to find routes off the streets had failed and/or there was a risk of significant harm’. Charity managers saw collaboration with the Home Office as part of an ‘assertive outreach’ approach.

The spurious logic behind this strategy was that being threatened with deportation would ‘encourage’ homeless people to leave the streets.

The St. Mungo’s review shows how, in July 2016, charity managers decided to switch from direct to ‘arms-length’ information sharing: ‘information [to] be provided to the Home Office by local authorities (not St Mungo’s & thus self-safeguarding). The local authority [to] provide the lead in information-sharing.’

The review admits that the change in policy was not communicated to frontline staff, and that at least one outreach team continued to share information directly with the Home Office until 2017.

St Mungo’s collaboration with the Home Office has aggravated the existing grievances of frontline staff, who voted for strike action in January 2020. The striking workers have demanded concrete reassurances that homeless people’s personal data will never again be shared for the purposes of immigration control.

A leaked email recently revealed that St. Mungo’s has been working with the reputation management firm BLJ London in an attempt to recover the charity’s image and weaken union opposition.

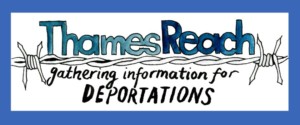

Thames Reach

Thames Reach was the most zealous charity participant in rough-sleeper removals. In one bid for an outreach contract, it marketed itself as having an ‘enforcement approach that cannot be replicated by other organisations’. The same document boasts ‘our links with the Metropolitan Police […] and UKBA [Immigration Enforcement] are excellent, having enabled successful hotspot operations and joint patrols’.[2]

Yet Thames Reach escaped much of the negative publicity around the Gureckis judgment, partly because their then chief executive, Jeremy Swain, adopted a different PR strategy, asserting the alleged necessity of charity collaboration with ICE rather than seeking to deny it. Thames Reach went so far as to invite a BBC journalist along to an ICE raid that led to at least one rough sleeper being ‘sectioned’ under the Mental Health Act.

In 2020 St. Mungo’s and Thames Reach continue to dominate the commissioning landscape for rough sleeping. The bosses who facilitated the Home Office’s unlawful policy have either been promoted or remain in place. Jeremy Swain, CEO of Thames Reach, left to become a government adviser on rough sleeping. Petra Salva, Director of Rough Sleeping, Migrants and Criminal Justice Services at St Mungo’s was given an OBE in 2019.

Petra Salva OBE

The Greater London Authority

The Greater London Authority (GLA), which was instrumental in bringing together ‘stakeholders’ to design rough sleeper removals policies between 2010 and 2017 [3], has cleaned up its act somewhat since the Gureckis judgment.

It has expanded its ‘Social Integration’ team and cultivated links with migrants’ rights organisations. But, as we show below, the GLA’s Housing and Land team has continued to work with central government to develop policies targeting homeless migrants.

Local authorities

Local authorities have been instrumental in sculpting an enforcement-based approach to rough sleeping, with Westminster council providing ideological leadership.

Westminster hosted Operation Adoze, the 2015 pilot project for rough sleeper deportations. The council then ‘intensely lobbied’ for the policy to be rolled out nationwide to send a ‘firm message that rough sleeping is not acceptable to those foreign nationals who […] choose to sleep rough’. [4]

The response of councils to the Gureckis judgment was one of consternation. In 2016 a number of local authorities had successfully bid for money from the government’s Controlling Migration Fund. The fund was designed to ‘mitigate’ the effects of migration on ‘resident populations’. More than £80 million has been paid out to councils through the fund, and many early bids were for money to fund enforcement against migrant rough sleepers.

A Newham council monitoring report from early 2018 shows council managers scrambling to change their approach ‘from enforcement to support’ in light of the High Court ruling.

The monitoring report for another bid, submitted jointly by Islington, Enfield, Haringey and Barnet councils, illustrates the frustration of council officers that outreach teams could no longer work with immigration enforcement. The monitoring questionnaire asks:

‘How is the LA working with ICE on enforcement activity? Have there been any issues with ICE / police being unable to commit resources to the CMF activity, which has affected delivery? Have you been able to undertake the number of raids / inspections? Any case studies you can share?’

The reply, written by an unnamed council officer, states:

‘ICE no longer engaging in any meaningful way. No incentive for elective rough sleepers to find alternative accommodation. There is a possibility that the LA will unable [sic] to meet some of the initial targets set in light of lack of engagement from ICE’ [5]

Housing Ministry

The Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government has been an overlooked but influential actor in policies targeting homeless people for deportation—not least in terms of framing.

The ‘impact summary’ PR kit issued by the ministry to councils in receipt of funding from the Controlling Migration Fund reveals the department’s commitment to playing up the ‘negative effects’ of migration.

‘Trafficking, children going missing, child sexual exploitation’ and ‘radicalisation’ are cited among examples of the ‘consequences of recent migration’ on ‘settled communit[ies]’. [6]

Collaboration Resurrected

The 2017 High Court judgment, combined with a backlash against ‘hostile environment’ policies after Windrush, forced the government and its allies to change strategy on migrant rough sleepers.

In this section we show how, in 2020, the same ‘stakeholders’ are relying on subtler approaches. These include the circumvention of consent-based information sharing and attempts to push removals under the guise of ‘support’.

‘A specific task in the public interest’: the Rough Sleeping Support Service

In August 2018, the government announced a new Rough Sleeping Support Service (RSSS) as part of its Rough Sleeping Strategy. The service sits within the Home Office’s Immigration Enforcement division and was initially overseen by the senior immigration officer who directed enforcement operations against rough sleepers until December 2017.

In public, the Home Office has been careful to frame the RSSS in terms of ‘support’ for migrant rough sleepers:

‘The team will help individuals to regularize their status where they establish a right to remain in the UK, and support them to return home as quickly as possible where this is appropriate.’ [7]

Internally, the scheme is described differently. In an email to officials at Westminster Council, obtained through an FOI request, the Home Office bureaucrat responsible for the scheme described it as a:

‘pipeline for local authorities to establish the immigration status of an individual rough-sleeper and consider whether there is an intervention which could be used to at least make some form of progress towards that individual being removed from the rough-sleeping scenario.’ [8]

In an early hint that the RSSS might have more to do with targeting ‘removable’ migrants than supporting homeless people, the official notes that:

‘practically, the service will have limited value in relation to EEA nationals [i.e. because they are more difficult to deport], excepting those who involved [sic] in criminality.’

Local authorities initially clamoured for involvement in the RSSS. The Home Office was forced to ask Westminster Council to stop telling other councils about the scheme for fear that meetings would be ‘oversubscribed’.

At a ‘roundtable’ meeting in early 2019, the Home Office told its ‘partners’ that rough sleepers would need to give their ‘informed consent’ prior to being referred to the service.

However, at a later meeting it was announced that a system based on consent had been deemed ‘unviable’, partly because of ‘the ability of rough sleepers to be able to withdraw their consent easily’. Instead, the service

‘would involve local authorities and their commissioned service providers, carrying out a specific task in the public interest which is laid down by the law. The task in question would be delivering immigration controls (and carrying out safeguarding responsibilities).’ [9]

The minutes of the April 2019 meeting, where this was proposed, clearly show attendees, including the GLA and St. Mungo’s, agreeing to the proposal: ‘Action: The group agreed the public task proposal would be developed.’ ‘Public task’ or ‘a specific task in the public interest’ refers to a legal basis for information processing under GDPR—in this case, ‘delivering immigration controls’.

Much remains unclear about the operation of the Rough Sleeping Support Service. Despite Freedom of Information requests, the government has refused to confirm data sharing arrangements for the scheme or to say how many rough sleepers have been referred. Among local authorities, only Kensington and Chelsea have admitted referring to the scheme.

‘Friendly officers from the Home Office’: infiltrating charities and faith groups

The Rough Sleeping Support Service, then, looks on close examination less like a ‘service’ for rough sleepers and more like a mechanism to circumvent consent-based data sharing. But the scheme is only one way in which the government is targeting homeless migrants.

For several years the Home Office has also been placing immigration enforcement officers in grassroots charities and places of worship, including temples and gurdwaras.

Religious sites and community centres have traditionally been places of refuge for undocumented migrants. Many are forced to sleep rough because it is illegal for them to work or claim benefits.

One community organisation, the Chinese Information and Advice Centre in Soho, advertises sessions run by ‘friendly officers from the Home Office’, noting that the ‘Home Office assures [sic] there will be no immigration enforcement during the surgery’.

It has also emerged that two Sikh community organisations — the Sikh Council and Sikh Youth and Community Service — have received hefty grants from the Home Office for helping to arrange over 400 ‘voluntary’ departures to India.

The Sikh Council has defended its involvement, saying ‘[there is no] conflict [of interests] in charities accessing government funds to alleviate poverty and suffering of the homeless’. But there is no evidence that any of the people who departed ‘voluntarily’ through these schemes received independent immigration advice about regularising their status in the UK.

The future

With the appointment in March 2020 of a new minister for rough sleeping who believes that ‘the number of rough sleepers has much to do with the very high levels of eastern European immigration over the last few years’, it looks likely that UK homelessness and border policy will continue to develop hand in hand for the foreseeable future.

Thousands of homeless EU citizens are likely to become undocumented after the end of the Brexit transition period. The protections from deportation and removal referenced in the Gureckis judgment will no longer apply to them. The ‘deportability’ of all EU citizens living in the UK will increase markedly from 2021, while the measures taken to clear the streets on ‘public health’ grounds as a result of COVID-19 risk turning rough sleepers into sitting ducks for enforcement once the pandemic is over.

Analysis: Understanding and resisting the deportation of homeless people

A close look at schemes targeting migrant rough sleepers shows how welfare, penal and border policies intertwine with each another in capitalist states. It also reveals the assimilation of charities into neoliberal governance structures, with the logic of ‘technocratic partnership’ undermining resistance to state oppression.

The disciplining of people seen as failing to engage in ‘productive’ work is as old as capitalism. But since the 1990s, social policy in the UK and elsewhere has been geared towards punishing, shaming or forcing into ‘workfare’ those whom the ‘fragmentation of labour’ under neoliberalism has left unable to secure steady waged work.

The same period has also seen a shift in the role of the voluntary sector. Where once charities filled specific gaps in an expanding welfare state, NGOs now compete to fill the gaping hole left by the welfare state in retreat.

Locked into a competitive process of tendering and contracting with government, charities’ autonomy and advocacy function is compromised by the imperative to meet specified ‘outputs’. The logic of commercial expediency has replaced the logic of care.

Legal challenge alone is not enough to resist these policies

Grassroots-led resistance has hindered efforts to deport homeless migrants. The Home Office’s rebranding of enforcement as ‘support’ betrays a recognition of the fact that ‘hostile environment’ policies no longer enjoy broad approval—if they ever did.

NELMA and PILC’s campaign against charity collaboration has influenced the homelessness sector. Where working with the Home Office was once seen as ‘best practice’, charities are now wary of the ‘reputational risk’ involved.

Activists concerned with holding the state to account must continue to pay close attention to the activities of NGOs. Charities should never be beyond scrutiny, especially now that many are forced to define the best interests of their ‘service users’ in terms amenable to their paymasters in government.

Campaigners need to monitor the relationship between charities, government and corporations. They must help homeless people, migrants and others to know which charities they can safely seek support from and which should be avoided. Alternative forms of solidarity must be elaborated.

But ultimately, opposing the deportation of homeless people means opposing the structures that underpin such policies. This means fighting the border regime writ large. Any system that assigns rights—and, implicitly, value—to human beings on the basis of what passport they hold must be resisted.

It also means taking action for housing. Now more than ever, in a time of pandemic, we must drive home the message that it is unacceptable for anyone to be homeless while homes stand empty.

Footnotes

1. In UK immigration law, ‘deportation’ refers to the enforced removal of a person ‘for the public good’, usually because they have committed a criminal offence. The enforced removal of a person solely on the basis that they have no leave to remain is referred to as ‘administrative removal’. Technically speaking, most rough sleepers forced to leave the UK under the ‘abuse of right’ policy were ‘administratively removed’ and not ‘deported’.

2. PDF 1: Agreement for the Provision of an Outreach Service to Rough Sleepers in the Borough of Tower Hamlets

3. Through the Mayor’s Rough Sleeping Group, later renamed the No Nights Sleeping Rough Taskforce. The group, now called the Life Off The Streets Taskforce, continues to direct homelessness policy in London.

4. City of Westminster Audit and Performance Committee Report, 30th June 2016, p. 26

5. PDF 2: NLP Monitoring Report_Redacted

6. PDF 3: 060218 Impact Summary Guide Final

7. PDF 4: Rough Sleeping Strategy Web, p.47

8. PDF 5: RSSS emails redacted

9. These three paragraphs are based on a FOI disclosure obtained by Liberty. The disclosure is not page numbered, but the documents referred to are: (a) ‘Rough Sleeping Support Service Guide and overview of issues for the Roundtable’, circulated by email on January 9th 2019; and (b) ‘Home Office Rough Sleeping Support Service Information sharing proposal’, circulated by email on 10th April 2019.