Stuart Delivery: La Poste’s gig economy gamble

The longest gig economy strike in the UK is today into its 50th day. Couriers organising through the IWGB union have taken strike action against Stuart Delivery in cities and towns including Sheffield, Blackpool, Chesterfield and Huddersfield. The strike has already won two of its demands: paid waiting times and a resolution to an insurance issue that was resulting in wrongful terminations. Couriers are still calling on Stuart Delivery to reverse the pay cut, apply a fairer pay structure and implement a hiring freeze in Sheffield.

According to the IWGB, the strike has now spread to Middlesbrough and is soon to start in Leicester and Dewsbury.

To support the strike, Corporate Watch has produced this profile of Stuart Delivery. In brief:

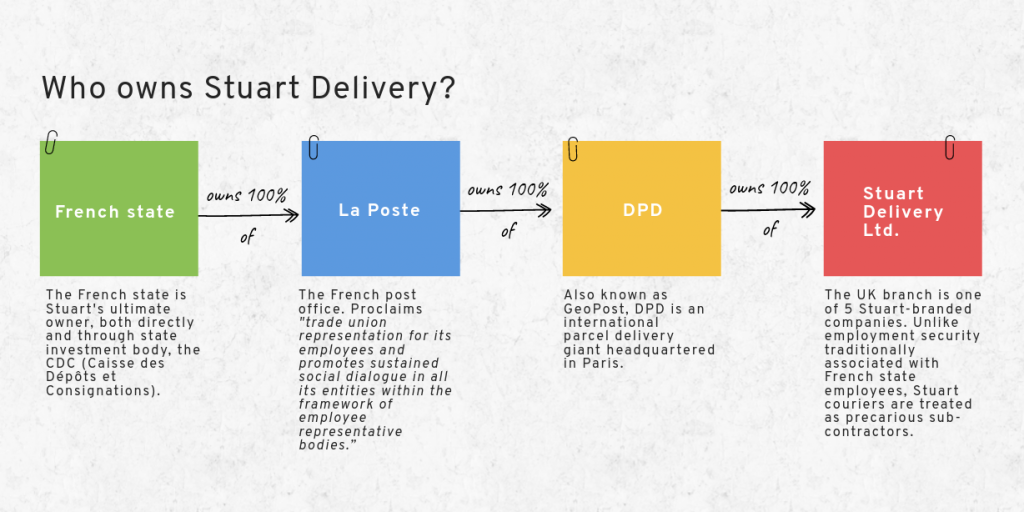

- Stuart Delivery is ultimately owned by the French state. It is a subsidiary of DPD delivery, which is itself a subsidiary of La Poste, the French state-owned postal service.

- La Poste says it guarantees labour rights and trade union representation for its employees – but leaves out Stuart couriers who are treated as precarious sub-contractors.

- Stuart is run by well-connected, ex-Lehman Brothers banker Damien Bon.

- Stuart is loss-making overall, but is making a profit from couriers’ deliveries. It is being bankrolled by DPD and has £7 million in cash in the bank.

Click here to find out more about the strike from the IWGB website.

The business model

Stuart’s pitch is instant delivery for everything. Instant (well, almost) delivery is standard in the food industry. If you live in a major city, you can order a takeaway from Deliveroo and hope to get it still relatively warm. So why not use the same kind of system to deliver other things “instantly” too – maybe a crate of beer from Brewdog, or some soap from Lush, or a dress from the Kooples, or your shopping from Carrefour (all of which are Stuart customers)? As Techcrunch puts it, Stuart’s offer is basically “Amazon Prime Now for local stores and merchants”, though all Stuart does is arrange the “last mile” – hooking up suppliers and customers in cities. It doesn’t have its own consumer-facing app, or arrange the shipping or warehousing itself.

Stuart also works for other delivery firms: in Sheffield, Stuart delivers for JustEat. This is why striking couriers have targeted McDonald’s: it contracts JustEat, which has in turn been contracting couriers through Stuart.

Who runs it?

Stuart was founded by Clement Benoit, Benjamin Chemla and Dominique Leca, but since 2017 its CEO has been Damien Bon. Bon used to work as a banker with US giant Lehman Brothers, infamous for going bankrupt in spectacular fashion during the 2008 financial crash. He then moved on to management consultants Boston Consulting Group before joining Stuart.

Damien’s corporate pedigree extends beyond his MBA from French business school INSEAD – the best in the world according to the Financial Times. The Bon family are well-connected. Xavier Bon has spent two decades running data monitoring firms and is a Foreign Trade Advisor for the Comité National des Conseillers du Commerce Extérieur de la France (CCEF), an association that represents and promotes French business interests abroad. He is a member of the CCEF’s Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur committee, where his role is to mentor budding start-up managers in their first forays into international markets. Advisors are nominated by the government and Xavier Bon has had his post repeatedly renewed over the past 16 years.

Who owns it?

So imagine: you’re a keen member of the gilded youth, out of top private school and the French “Grandes Écoles” elite universities, maybe finished off with an MBA, perhaps a year or two in investment banking. Now you’re ready to make your mark. Hedge fund, perhaps? Civil service fast track? But those are just so 20th century. You really want to be where the action is? Get a mate or two together and do your own tech startup. Know nothing about IT? No worries, you’ll hire a few back-office geeks for that. The thing is the buzz, the funky name. Think Uber, Deliveroo. Think TikTok, Tinder, Airbnb. It’s all about bringing people together – be it with a hamburger or a hot date – and you’re the guys in the middle with the magic algorithm. You’re wild, you’re hot, you’re “disrupting” old business models to actualise instant delivery of every possible human craving. (Actually, it’s the couriers who are out doing the deliveries, but let’s not get bogged down in mundane details).

Small obstacle: there are another thousand MBAs out there with the same idea. They’ve all got a logo, a downtown office and a team of IT geeks. How can you thrust yourself to the front of the pack? For the first five years at least, you’re going to be losing big amounts of money as you try to undercut the competition. And for every Facebook or Amazon, there are a thousand other failed tech companies that no one remembers the names off.

The only hope: attract big capital to back you through those first few years, and take the gamble that your company will sell. So get working those business school connections, get Dad to chat with a few mates in finance.

The classic way is to sell a stake in your start-up to “Private Equity” or “Venture Capital” funds. These are investment firms that specialise in buying chunks of businesses, then look to sell them on in a few years once they have established themselves. Take Deliveroo, for example. Set up in 2013 by William Shu, it’s lost hundreds of millions pushing rapid expansion into new cities and countries. It keeps going because a bunch of US and Hong Kong private equity investors, plus Amazon from 2020, keep sinking in cash. Then in 2021, on the back of the COVID-19 delivery boom, it launched an Initial Public Offering, (“IPO”) – selling shares on the stock market to get its investors back some of their money.

Stuart’s founders followed a similar path. But there’s one stand out point. Whereas most start-ups look for help from private investors, their big daddy backer was the French government.

La Poste, the French postal service that is 100% owned by the French state, put in €22 million of initial funding in 2015, even before Stuart had been officially launched. According to the website Techcrunch, La Poste stuck in the money “largely off the back of an idea and based on the track record of its three founders.” Two years later, La Poste went all in – it bought out Stuart 100%.

So we end up with a situation that some may find contradictory, but just might be the quintessence of 21st century hyper-capitalism. The French state, via its highly-unionised national post office, owns a tech company run by ex-bankers pushing the limits of gig economy precarious employment.

Since 2017, Stuart has been 100% owned by La Poste, which in turn is 100% owned by the French government. La Poste’s accounts describe Stuart as an “uncontrolled subsidiary”. That is, it is run as a separate company with its own independent management. But we shouldn’t let La Poste get away from taking responsibility for what Stuart does – La Poste is still the ultimate legal owner.

To break down the corporate web in a bit more detail: Groupe La Poste has a number of subsidiaries and divisions. These include La Poste itself; and also DPD, the international parcel delivery giant. It is this division that bought Stuart in 2017.

In legal terms, Stuart is in fact a number of companies. Three are registered in France: SRT France, SRT France Logistics, and above them the parent SRT Group. And then there are local companies in the UK (Stuart Delivery Ltd), Spain (Stuart Delivery SL), plus the newest one in Italy (SRT Italy SRL). All of these are 100% subsidiaries of DPD, which itself a subsidiary of La Poste.i

Labour rights for posties, but not couriers

As a national institution, and with a strong history of unionisation, La Poste proclaims its reputation on labour rights and trade union recognition. So what is it doing owning a gig employer like Stuart?

La Poste publishes an annual “Vigilance Plan” which sets out its commitments on “human rights and labour law”, as well as other social and environmental issues.ii This clearly commits that La Poste:

“has trade union representation for its employees and promotes sustained social dialogue in all its entities within the framework of employee representative bodies.”

“All its entities”, it seems, save one – Stuart. Somehow this one subsidiary appears to be exempted. La Poste bosses are clearly concerned to put a positive gloss on this exception because the Vigilance Plan contains a dedicated point on Stuart. This says:

“the Stuart subsidiary, which puts clients in contact with independent couriers, has been a pioneer in its field by developing a responsible social model”iii

Here La Poste is keen to clarify that Stuart couriers are not actually employees, so don’t need the same rights. But they do get a “responsible social model” which includes: “reinforced social protection (financed by Stuart from the first euro of revenue)” and “privileged access to professional or work-linked training”, as well as “easier access to funding for professional equipment and, finally a continuous listening, recognised by the delivery community.”

Sounds nice. In practice, couriers say they are denied basic employment rights by being wrongly classed as self-employed. This is despite both a UK Employment Tribunal and Employment Appeal Tribunal deciding that a Stuart courier should be classed as a worker.

Stuart couriers say they started the current strike after the company enforced a 24% pay cut in December 2021, which saw base pay rates slashed on most deliveries from £4.50 to £3.40.

Photo by Hello I’m Nik on Unsplash

How much money is Stuart making?

Accounts filed at Companies House show Stuart Delivery’s made £41 million in revenue from customers in the UK in 2020, just over double the £20.5 million it had made the year before. Once all its costs were taken into account, the company made a loss of £7.4 million. However, the accounts show its deliveries are profitable: it made a ‘gross’ profit of £12.9 million in 2020, at a ‘margin’ of 31.5%. If it paid its couriers more, then gross profit would decrease, but a 31.5% margin gives the company wiggle room to increase pay while still making money from its deliveries (its margin is significantly better than that of its rival Deliveroo when we profiled that company last year).

So why is Stuart losing £7.4 million overall? Because of the £20.3 million it is spending on ‘administrative expenses’. The accounts do not break these down but they are likely to include money it is spending in its drive to expand aggressively across the UK, plus head office, software and other costs. Staff costs – i.e. people they employ on contract, unlike their couriers – increased to £5.8 million in 2020, up from £1.7 million the year before. At the time of writing, Stuart was advertising for over 40 jobs in management, data analysis, HR and product design in the UK alone.

Stuart can afford to continue because of financial support provided by its owner DPD (and therefore La Poste and the French state), which directors say has left it with a “healthy cash balance”. Stuart Delivery Ltd had £7 million in cash in the bank at the end of 2020, the last date for which accounts are available. Money owed to its parent companies are mounting up (£46 million as of the end of 2020), but directors say support is guaranteed for at least until the end of 2022.

Some people are doing very well from the company even while it is loss-making. The accounts show an unnamed director – presumably Damien Bon – was paid £2.2 million in 2020. So couriers have every reason to demand better pay and conditions: those at the top are already making money from it.

“Stuart CEO Damien Bon, who used to work for Lehman Brothers, is using French taxpayers money to bankroll the exploitation of majority-BAME workers in the UK. Despite £2 million payouts to top execs, huge profit margins on deliveries, and £7 million sitting in the bank, couriers are being forced to work 12 hour days on poverty pay to make up for the 24% cuts handed out by Stuart. That’s why the couriers have been on strike for 50 days now and why the strike is still spreading, because this is a fight for survival. With the cost of living rising to crisis point, couriers cannot go on like this. We will continue to fight until these key workers are given the pay that they deserve.”

La Poste will hope to make good money from its investment too. The endgame is presumably either to cash in from future profits and dividends (made from couriers’ work), or a profitable sale. It is instructive that the company’s ‘key performance indicators’ chosen by management are revenue and gross profit: they are focused on expanding and eking out money from deliveries, not overall losses.

Will it work? Will Stuart ever make money for La Poste? All start-ups spin a good story about how they have a unique model to address a market need – and some do become profitable. But many crash, or fade into obscurity, without ever making a penny. In short – La Poste is taking a big gamble with public money.

Notes

i See Groupe La Poste Annual Report 2020 p444: https://le-groupe-laposte.cdn.prismic.io/le-groupe-laposte/8438b095-1a9a-477a-8a25-9699ee41876a_GLP2020_UDR_EN_mars_2021.pdf

And latest annual accounts for all Stuart Companies. For Stuart Delivery Ltd this is available free from Companies House from this link: https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/09790251/filing-history

Unfortunately French and Spanish company accounts are not available free of charge

ii See Annual Report 2020 Appendix 1

iii Annual Report 2020 Appendix 1 p537

Header image: Stuart courier strikers in Yorkshire. Photo: IWGB