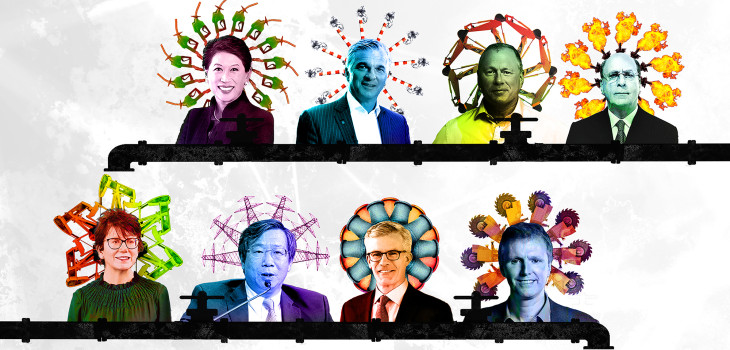

Carbon Cash Machine: meet the investors running – and destroying – our world

As part of our investigation with Queen Mary University’s Centre for Climate Crime and Justice into the mammoth payouts made to BP and Shell’s shareholders, we examined the top eight investors of both oil companies, breaking down these faceless, murky entities as best we can. All eight are hugely powerful corporations, holding shares in many companies listed on the world’s stock exchanges.

We contrast the voluminous quantities of greenwash they spout, often facilitated by the mainstream media, with the stark reality of their profiteering.

Meet the investors running – and destroying – our world.

Contents:

#3. Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM)

#4. Legal & General Investment Management (LGIM)

#6. State Street Global Advisors (SSGA)

Note: For more on our sources, please see the full report here.

#1: BlackRock

#1: BlackRock

BlackRock, Inc. is an asset management company, investing money on behalf of its clients in return for fees. It controls approximately $8.5tn (£6.7tn) in investments, making it the largest asset manager in the world – a position it has held since 2009. It is also the largest index investor, with two thirds of its assets in passive funds. Headquartered in the US, it has around 16,000 employees in over 35 countries servicing a million clients. Its clients are categorised as “retail” – for example individuals saving for retirement – and “institutional”, such as insurance companies and pension funds. Through the assets it manages, BlackRock holds shares and debt in thousands of companies.

BlackRock was founded in 1988 by eight financial services professionals, including chair and chief executive officer (CEO) Laurence ”Larry” Fink. It became a publicly-traded company when it listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1999. The company grew via a series of competitor acquisitions, and cemented its position as the world’s largest asset manager with the purchase of Barclay’s Global Investors (BGI) in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Major shareholders include many of BlackRock’s competitors; the most significant stake is held by Vanguard Group at approximately 9% – its closest (apparent) rival in the asset management space.

The scale of investments controlled by BlackRock affords it massive influence within the financial system and the US state. In 2008, it worked with the US government on the latter’s response to the financial crisis, advising it and helping manage the distressed and toxic assets it acquired in market interventions. It also had extensive involvement in the state response to the market impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The company has made a number of high-profile hires from Barack Obama’s presidential administration. These include Brian Deese, who had helped negotiate the Paris Climate Accords, and was brought on to lead on sustainable investing. Several of these appointees subsequently returned to Washington to work for Joe Biden.

The company’s political lobbying and donations reached a record $3.5m (£2.8m) in 2022.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Claims vs Reality

On the face of it, BlackRock has made prominent commitments on climate change in recent years, promoting “sustainable investing” and a transition to “net zero” by 2050. The concept of “net zero” or “carbon neutral”, means the amount of carbon pumped into the atmosphere is balanced out by what is removed. BlackRock has signed up to industry initiatives including Net Zero Asset Managers (NZAM) and Climate 100+; investor pressure groups aiming to convince major polluters to reduce carbon emissions.

Recent data released by environmental NGO Urgewald indicates that BlackRock has at least $263bn (£208bn) invested in fossil fuels via its funds; indeed, BlackRock and Vanguard together reportedly represent 17% of institutional investments in the fossil fuels industry.

Like Vanguard, BlackRock voted against 80% of climate-related motions at the annual general meetings (AGMs) of FTSE 100 and S&P 500 firms between 2015 and 2019. Meanwhile, BlackRock’s ESG-labelled funds were found to be the worst for deforestation risk in a 2020 analysis.

A series of investigations published by Reclaim Finance have also contrasted BlackRock’s investments with their ESG messaging. They pointed to $85bn (£67bn) in managed assets invested in coal companies in 2020, including $24bn (£19bn) in firms with expansion plans, despite a policy to “exit thermal coal”. Votes against climate resolutions in shareholder meetings had in fact increased to 88% that same year. A 2021 report exposed the $75bn (£59bn) BlackRock had invested in companies engaged in environmentally ruinous tar sands projects, while Reclaim Finance’s 2022 report, “The asset managers fuelling climate chaos”, examined BlackRock’s role in the corporate debt of major carbon emitters. BlackRock was found to be one of the biggest bondholders of coal companies with expansion plans, and one of the top bondholders in an analysis of more than 300 oil and gas companies. It was also ranked amongst the “worst in class” in a recent Share Action analysis of asset managers’ actions to address climate breakdown.

Despite its ESG commitments, BlackRock simultaneously promotes its extensive investments in carbon emitters. In correspondence with US state officials, it has described itself as “perhaps the world’s largest investor in fossil fuel companies”. When faced with an anti-ESG backlash, it emphasised the $170bn (£135bn) it had invested in US energy companies, denying accusations of any boycott or divestment strategy. In the UK, it told the parliamentary environmental audit committee last October that it would not end investments in coal, oil or gas, citing its fiduciary duty to clients over a decarbonisation agenda. Contemporary data from financial databases on shareholdings in major US, European, Chinese and Middle Eastern energy and fossil fuel companies shows that BlackRock controls the largest private share. As BlackRock itself says, its focus on climate is as capitalists, not environmentalists.

UK location: 12 Throgmorton, City of London.

BlackRock CEO: Laurence “Larry” Fink

Laurence “Larry” Fink is the face of BlackRock. He has been chief executive officer (CEO) since he co-founded the company in 1988, and now also serves as chair of the board of directors and the global executive committee. He has been called the “undisputed king of Wall Street” by the Financial Times, and is considered to be worth approximately $1bn (£792m). He was paid $36m (£29m) by BlackRock for 2021, up from nearly $30m (£24m) the year before. He holds $312m (£247m) in company stock at current market rates.

Prior to BlackRock, Fink became the youngest managing director at investment bank First Boston, before a $100m trading loss on an interest rate bet in 1986 ended his career there. He was a pioneer of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the financial product which would go on to be the trigger of the 2008 financial crisis. In 2021, he expressed an ambition to do for sustainability what he had done for mortgage-backed securities.

Fink has been at the forefront of BlackRock’s attempt to frame itself as an environmentally responsible investor. The topic has featured consistently in his most high-profile communications to clients and to the CEOs of major companies. However, he has faced calls to stand down by one investor, Bluebell Capital Partners, over the hypocrisy of the company’s continued fossil fuel investments, and has been named among the “dirty dozen” of climate crisis villains.

Fink and his wife Lori own a number of rural estates in a wealthy enclave of North Salem, New York state, dubbed “Billonaires’ Dirt Road”.

#2: The Vanguard Group

#2: The Vanguard Group

Vanguard’s ethos? In the words of CEO Tim Buckley: “Climate change is a material risk but it is only one factor in an investment decision.”

Vanguard Group, Inc. is an investor-owned, US global asset manager, currently managing approximately $7.7tn (£6.6tn). Second only to BlackRock, Vanguard has over 30 million investors across 400 funds worldwide. The company’s founder Jack Bogle was the originator of the passive index fund in the mid-1970s, and it remains largely an index investor, allocating funds to every major company on the world’s exchanges – including, of course, many of the biggest polluters.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Claims vs Reality

In 2015, the same year the Paris accords were signed, Vanguard overtook competitors to become the second biggest investor in both BP and Shell. Speed forward to 2023 and Vanguard’s stake in these two big polluters has doubled.

Vanguard’s growing investments in the two oil multinationals have paid off nicely: from 2016 to 2022, Shell paid nearly £3.4bn to Vanguard, compared £686m in the previous seven years.

The company currently holds the ignominious title as the largest institutional investor in fossil fuels, slightly ahead of BlackRock,with at least $269bn (£213bn) invested in the industry. Since the 1980s, it has offered specific funds for investors intent on funding the sector. These include the Vanguard Energy ETF, which is 100% comprised of firms involved in the production of fossil fuels, including coal; and Vanguard Energy Fund Investor Shares. Apart from Shell and BP, these funds are also pouring money into companies such as ConocoPhillips, Total, Exxon Mobil and Chevron.

But Vanguard’s investment in climate wreckage is not ring-fenced to these special energy funds. According to the Financial Times, in 2022 only 17% of even Vanguard’s actively-managed funds were in keeping with with aim of net-zero by 2050. Up until the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Vanguard had no qualms about investing in one of the world’s biggest gas producers, Russia’s state-owned Gazprom. Meanwhile, Vanguard had €1bn (£792.5m) invested in German coal giant RWE when the latter the evicted and destroyed Lützerath village for the expansion of the Garzweiler mine this January, despite the resistance mounted by 35,000 protestors, including Greta Thunberg.

Alongside BlackRock, Vanguard is one of the world’s top investors in the coal industry – with over $100bn (£79.3bn) invested in the sector.

As paltry as ESG funds may be, Vanguard offers just seven of them – representing a mere 0.38% of its assets – and trailing behind BlackRock in this respect. These funds invest in companies like Barclays (the UK and Europe’s top fossil fuel financier), JP Morgan, and Bank of America (both in the top four fossil fuel financiers over the last six years).

Vanguard eventually joined – and recently pulled out of – the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative, because its “voice was being drowned out”. Although there was talk of other big investors defecting, so far only Vanguard and Green Century Capital Management have quit, leaving behind well over 500 other competitors. The company’s approach to corporate responsibility is summed up by CEO Tim Buckley:

“We don’t believe that we should dictate company strategy…It would be hubris to presume that we know the right strategy for the thousands of companies that Vanguard invests with…. [Vanguard is] not in the game of politics”.

According to Majority Action, the company scored lowest of all asset managers in shareholder resolutions to disclose lobbying activities – with zero motions supported. This means Vanguard is actively preventing transparency about corporate lobbying activities of companies such as BP and Shell.

UK location: 25 Wallbrook, City of London.

Vanguard CEO: Mortimer J “Tim” Buckley

In 1991, Mortimer J “Tim” Buckley, fresh out of a BA in Economics at Harvard, joined Vanguard as assistant to the company’s founder, Jack Bogle. Buckley steadily rose up the ranks, serving as Chief Investment Officer before becoming the CEO in 2018 and then Chairman in 2019.

On an autumn day last October, Buckley’s Pennsylvanian mansion doorstep was the site of a Quaker-led action. Fifty protestors with red t-shirts emblazoned with “Vanguard Invests in Climate Destruction” delivered a letter to Buckley, unfolded deck chairs, and sat in silence for 30 minutes in front of the house.

Since 2021, Buckley has lent his expertise as an Industry Governor for the US Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). The authority supervises the integrity of financial markets and investors such as Vanguard.

Buckley’s annual pay cheque is unknown (salaries for Vanguard top brass are a closely-guarded secret), but the company reportedly provides “very high compensation levels” for managers. His predecessor’s salary, at the end of his term, was estimated to be $10-15m (£8 -12m) annually.

#3: Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM)

#3: Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM)

Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) is the day-to-day fund manager of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) – one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) The fund was established in the 1990s to protect the revenue made from oil in the North Sea. Norway is now the largest oil-producing state in Western Europe.

In 1998, NBIM was formed to manage and grow the fund, and hedge risks from fluctuating oil prices by investing entirely in international markets. NBIM describes it as “the Norwegian people’s piggybank”. The fund generates income from oil and gas production, although the majority has been acquired through investments in the stock market, government and corporate bonds, and real estate.

NBIM is part of Norway’s central bank, Norges Bank, and the fund is ultimately managed on behalf of the Ministry of Finance. It is therefore an intermediary body owned by the Norwegian government.

Much like the index investors in this list, NBIM’s holdings are truly global, with an average 1.5% share in all the world’s listed companies. Details of current and past countries where the fund is invested can be found (and filtered) here. Its largest holdings by late 2021 were by far in the US (43.3%), followed by Japan (8.4%), and the UK (6.9%).

Although the fund made a negative return on its investments last year of -14%, its market value was still a massive Kr12tn (£917bn), largely due to the soaring price of oil and gas.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Claims vs Reality

NBIM’s portrayal of itself versus its actual role in climate destruction is perhaps best painted through the example of its CEO, Nicolai Tangen, riding an e-scooter to work on his first day managing one of the world’s largest oil funds. The extreme dragging on ESG policies by Republicans in the US, exploited by NBIM’s greenwashing PR exercises, have portrayed the wealth manager and its CEO as climate-saving warriors. Its publications are riddled with all the common markers of greenwash, but a quick glance at NBIM’s accounts and actions exposes little substance behind proposals, commitments, and “engagements”.

NBIM has made huge profits from oil and gas companies, including BP and Shell. As one of the top shareholders of both, between 2016 and 2022 it received nearly £1bn in payouts from BP, and around £2.3bn from Shell. By early 2023, NBIM’s holdings in BP and Shell were valued at £2.7bn and nearly £5.4bn, respectively.

A quick glance at NBIM’s voting history for companies like BP, Shell, Exxon Mobil, and TotalEnergies, inevitably exposes a very different picture to that described in the company’s ESG literature. Despite sensational threats to vote against directors who don’t prioritise climate targets, NBIM has repeatedly voted to re-elect directors of oil companies such as BP and Shell. It will come as no surprise to readers to learn that this oil fund manager has also voted against numerous resolutions by activist shareholders to curb emissions.

Despite its losses on investments, NBIM enjoyed a record injection of cash to the fund in 2022 from the Norwegian state’s oil and gas revenues, thanks to the rise in oil prices globally. This serves as a crucial reminder that for all its tough talk on climate change, the company remains fundamentally reliant on revenues from hydrocarbons.

Norway’s fossil fuel industry continues to expand, and with the country planning to offer energy firms a record 95 oil and gas exploration blocks in the Arctic, we can expect to see the continued growth of the oil fund too.

UK location: 3 Old Burlington Street, Mayfair

NBIM CEO: Nicolai Tangen

NBIM’s CEO, Nicolai Tangen, was recently referred to as the “trillion dollar-man”, and “the most influential person in the world you have probably never heard of”. He made his fortunes as a hedge fund manager, having run his own fund, AKO Capital, for nearly fifteen years. With a net worth of £550m, his wealth had been large enough for him to make The Sunday Times’ “Rich List 2020”. Tangen was a former intelligence officer in the Norwegian military, and currently owns the world’s largest Nordic modernist art collection.

When Tangen was appointed to CEO in 2020, his extravagant lifestyle and background as a hedge fund manager raised suspicions about his fitness for the job looking after the state’s wealth. Eyebrows were raised still higher given that his name hadn’t been put forward in a shortlist of candidates for the role.

The appointment followed a lavish, all-expenses-paid-for event that he had organised for an array of high-powered corporate and government guests – including the outgoing CEO, Yngve Slyngstad. Tangen reportedly “spent millions of pounds flying 120 movers and shakers from across the world”. Guests included the former Conservative leader, William Hague; chef Jamie Oliver; and British Museum director Hartwig Fischer. The exclusive list of invitees attended a diverse range of seminars before being entertained by a one-hour, one-million-dollar live performance by Sting. Think Ed Norton’s tech billionaire’s get-together in The Glass Onion and you get the picture.

Tangen also came under scrutiny for his large personal investments in tax havens and in particular, a case between HMRC and AKO Capital regarding deferred tax payments.

#4: Legal and General Investment Management (LGIM)

#4: Legal and General Investment Management (LGIM)

LGIM is another global asset manager, and Shell’s fourth-largest shareholder. It’s a subsidiary of Legal & General Group PLC, a British multinational financial services firm and one of the country’s largest insurance businesses. Founded in 1836, the Group is a major pension fund manager in itself. But it is perhaps better known for enabling other pension funds to hedge their risks – associated, for example, with market volatility, or people living longer than expected – and acting as a buffer between the market and its pension fund clients.

As part of this, LGIM has become the UK’s largest asset manager, controlling over £1.2tn in investments. The corporate group is made up of hundreds of companies. Headquartered in London, it has approximately 10,000 employees worldwide. It was headed by outgoing CEO, Sir Nigel Wilson since 2012. A Brexiteer, Wilson was part of David Cameron’s business advisory board in the lead-up to the 2016 referendum. He has recently been replaced by António Simões, a former Santander boss.

Legal and General’s top shareholders include BlackRock, Vanguard and Capital Group.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Claims vs Reality

The Group’s current mantra is “Inclusive Capitalism”: of all the asset managers listed in this series, LGIM and its parent company try the hardest to paint themselves as responsible investors. LGIM is a signatory to the Net Zero Asset Managers pledge for a “net zero asset” portfolio by 2050, and has been rated favourably by Majority Action for its climate action in the form of targeted voting and investment sanctions.

In contrast to most of Shell and BP’s other top investors, its stake in both companies has diminished steadily, while its recent voting record on climate targets more generally makes its actions more consistent with its ESG claims than many others. It has even partnered with US NGO Environmental Defense Fund to encourage businesses to “go green”, and its ESG targets became a criterion for awarding bonus shares under the Group’s management performance share plan in 2021. Executives and directors such as Nigel Wilson – who was awarded £2.6m in shares last year under the plan – now therefore stand to directly benefit from hitting ESG targets.

LGIM has reduced its shares in BP by 62% and in Shell by 43% since the Paris Agreement. Nevertheless, of the top investors in this list, only BlackRock has benefited more than LGIM from its investments in the two oil majors: LGIM has received over £2bn in returns on those investments since 2016; and in 2022, LGIM received £405m from these holdings. This is considerably more than in 2016, despite owning fewer shares.

Legal & General as a whole has at least $18bn (£14bn) invested in fossil fuels. Back in 2019, LGIM defended its choice to include Shell in the top ten holdings of its “climate-conscious” Future World fund in the face of criticism from one of its pension fund clients. Two years later, LGIM was apparently on the side of activists, voting at Shell’s AGM to reduce emissions. And yet, today, investing in LGIM’s fund “RAFI Fundamental Global Low Carbon Transition Equity Index”, means investing in companies such as Shell and Exxon Mobil – as well as top fossil fuel banker, JPMorgan Chase.

In spite of being held up by some as an almost exemplary shareholder, besides oil and gas, the company still invests heavily in coal. Latest figures indicate that the company has $6.1bn (£5.3bn) resting in firms associated with coal mining or production, such as Duke Energy and Glencore.

UK location: 1 Coleman Street, City of London

LGIM CEO: Michelle Scrimgeour

In the words of LGIM CEO Michelle Scrimgeour, LGIM’s climate commitments are “not principles before profit”, but “simply good business sense”. Michelle Scrimgeour joined LGIM as CEO in 2019. Her career in the sector began in the late eighties, when she held several senior positions at asset management firms, including BlackRock, one of Legal and General’s top shareholders.

Today, Scrimgeour also sits on the board of directors of the UK’s trade body for investment, the Investment Association. In 2021, she had the chance to put LGIM’s interests at the heart of climate crisis negotiations as the co-chair of the UK Government’s COP 26 Business Leaders Group, alongside COP 26 president Alok Sharma. Laughably, Scrimgeour used her platform to insist on the need for clear rules to guard against greenwashing. Scrimgeour is also a member of the Women in Finance Climate Action Group. Presented as an industry role model, Scrimgeour makes it on the Financial News’ top 100 influential women in finance year on year. Before Scrimgeour stepped down from the group’s executive board in 2020, the company disclosed that she had received a salary of £2.4m.

#5: UBS Asset Management

#5: UBS Asset Management

UBS Asset Management AG is a subsidiary of the Swiss-based bank and financial services firm, UBS Group AG. UBS Asset Management handles investments for corporate and private clients, primarily through actively-managed funds. It also has a relatively small portion ($443m; £351m) invested in passive funds, a figure which is expected to grow significantly since UBS’ recent takeover of Credit Suisse – a company with large investments in passive funds.

The parent company is Switzerland’s biggest bank, and now the world’s fourth largest by asset. Since the Credit Suisse merger, the bank’s assets are in fact now twice the value of Switzerland’s GDP, sparking fears over its power and the Swiss economy’s exposure to a single company. UBS Group has been described as the world’s largest private bank – meaning that through its “wealth management” division, the company services rich individuals with advice on topics such as taxation, wills and trusts, and by managing their investments.

The company’s roots are apparently several centuries old, though its current incarnation is the product of the 1998 merger of the Union Bank of Switzerland and Swiss Bank Corporation. UBS AM has $1.1tn (£872bn) in assets under management; this is expected to grow significantly since the Credit Suisse takeover. The Group as a whole now has $5tn (nearly £4tn) in invested assets ($2.8tn prior to the takeover). Its fortunes were already growing before the merger: in a year with rising commodity prices and inflation triggered notably by the war in Ukraine, last year the Group made a net profit of $7.6bn (£6bn) – an annual increase of around £137m. With the dust of the Credit Suisse affair still settling, we have yet to see quite how much the acquisition will benefit the company.

The top shareholders of UBS Group are Dodge & Cox and Artisan Partners LP – both privately-owned US active fund managers – as well as BlackRock, Vanguard and Norges Bank Investment Management.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Claims vs Reality

The company calls itself “a leader in sustainability”, with UBS AM having been one of the founding signatories of the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative. UBS AM plans to become “net zero” across the whole business – including so-called “Scope 3 emissions” – by 2050. Scope 3 emissions, by UBS’ own definition, refer to:

“…emissions resulting from activities from assets not owned or controlled by the reporting organization, but that the organization indirectly impacts in its value chain”.

These can be interpreted as covering, for example, a bank’s investments. However, UBS’ application of this criteria is ambiguous. While its definition of Scope 3 emissions appears to include financing fossil fuel exploration and production, it does not seem to include their transportation and trade. 2021 has been called the “year of ‘net zero by 2050’ pledges”, with many banks and asset managers making bold public commitments to the goal. The 2050 target was agreed by the IPCC. However, it is now clear that the date is far too late; by that point climate change will be truly irreversible. And research shows that the top fossil fuel companies are – unsurprisingly – nowhere near on target. Net zero, along with “impact investing”, is therefore just another distraction with a catchy name, allowing companies to “burn now, pay later”.

Like other asset managers, UBS AM offers a number of “socially responsible” or “low carbon” funds for investors. But the Group has reported that its so-called “sustainable investments” – for example in energy-efficient properties – currently in fact represent just 6.8% of its overall portfolio. And by its own admission, 7.5% of the Group’s customer lending is still linked to carbon-related assets; in January 2023, it had at least $20.8bn (£16.5bn) invested in fossil fuels in the form of shares and bonds. Among the risks identified by the group in its latest annual report are “concerns about greenwashing, where UBS may be subject to reputational risk if not fully aligned with sustainability-related criteria”. It specifically cited the “new standards and rules” being developed in some countries, and the “increased risk that UBS may not comply with all relevant regulations”. In other words, the company is clearly worried about the impact on its reputation if it fails to put in place adequate sustainability measures.

UBS AM has made over £1bn in dividends and buybacks from its investments in BP and Shell since the Paris Agreement. This will have benefited top management and directors, as well as its own shareholders. Despite its bold declarations, UBS Group also has approximately $5.6bn (£4.45bn) invested in the thermal coal industry through both shares and bonds. UBS AM notably has no coal exclusion policy for its passive funds. Its holdings are unlikely to decline following the acquisition of Credit Suisse, a company which financed the fossil fuel industry to the tune of nearly $91.8bn (£73bn) from 2016-2020.

UK location: 5 Broadgate, City of London.

UBS CEO: Sergio Ermotti

Until April 2023, UBS Group was being steered by “Europe’s best-paid bank boss”, Dutch banker Ralph Hamers. However, he was bumped out of position after less than three years following the surprise return of Sergio Ermotti, who was brought back to oversee UBS’ takeover of Credit Suisse.

Ermotti previously served almost a decade at the helm of UBS until 2020, and is credited with turning the company’s fortunes around during the 2008 financial crisis. He apparently drafted plans to acquire Credit Suisse “three or four times” during his previous tenure, making him an obvious choice to oversee the merger.

Ermotti’s banking career began aged 15. He worked at Citibank, UniCredit Group and Merrill Lynch, before several years leading insurance firm Swiss Re.

You have to wonder whether the change in leadership might have had anything to do with the revival of a criminal investigation into former CEO Ralph Hamers for suspected money-laundering from his stint at his previous bank, ING. The case against Hamers had been already been investigated twice, with ING settling out of court in 2018 for €775m (£673m). The 50% pay rise Hamers received at ING at the time reportedly led to hundreds of ING customers shutting their accounts in protest. In spite of the ongoing investigation, Hamers received a salary of $13m (over £10m) as boss of UBS in 2022 – an annual increase of 11%.

#6: State Street Global Advisors

#6: State Street Global Advisors

State Street Global Advisors (SSGA) is one of the world’s largest asset managers and the smallest of the “Big Three” index fund managers. It is the asset management division of its parent company, the finance giant, State Street Corporation. SSGA’s clients include pension schemes, corporations, investment consultants, endowments and foundations, governments, and other asset managers.

SSGA currently manages approximately $3.8tn (£3.3tn) in assets. The company has over 2000 clients in 58 countries; its largest geographical market is the US, where it is headquartered.

State Street Corporation’s largest shareholders mostly consist of investment management firms. Collectively, these top ten shareholders hold around 40% of the shares. Vanguard holds the largest, at nearly 13%; it is followed by BlackRock, Dodge & Cox, T Rowe Price Associates and Capital International Investors (owned by Capital Group).

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Claims vs Reality

The last decade has seen SSGA write its history as one concerned with matters of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues. It has advertised the launch of an ESG Money Market Fund, as well as an ESG scoring tool called R-Factor. A closer look at SSGA’s policies and ties to the oil and gas industries, however, thoroughly undermines these gestures.

State Street as a whole has at least $133bn (£106bn) invested in fossil fuels. SSGA has no exclusion policy for oil and gas – including for its “passive” assets, which are worth over $3tn (£2.4tn) – and fails to exclude coal from its investments. Since 2016, SSGA has received cash earnings of over £1.1bn from BP, and over £1bn from Shell. And SSGA’s total shares and bonds in 12 major oil and gas companies with the biggest short-term expansion plans – including both BP and Shell – exceed $83bn (over £66bn).

The company’s voting record reveals that despite its feeble attempts at greenwash, SSGA has been significantly obstructing action on climate change. Data from the first six months of 2021 and 2022 shows an actual decrease in SSGA’s support for climate-related proposals – apparently on the grounds of their “prescriptive nature”. And by its own admission, in the first six months of 2022 SSGA voted against all transition to renewable energy proposals, and against “operational changes in response to climate change” in 86% of cases. SSGA explained its opposition to action on climate change with the following:

“we have not been supportive of proposals that request a specific operational change such as phasing out a product or business line within a defined timeframe, decommissioning assets, or requesting a transition to renewable energy…”.

All motions made by oil and gas company shareholders to scale back greenhouse gas emissions in line with targets agreed in the Paris Agreement were either voted against or abstained on by SSGA. It has also voted against so-called dissident CEO candidates, such as those with expertise in renewable energy.

SSGA has rejected calls for divestment, describing it as an inadequate “option for investors” that “is seldom an effective tool”. As shown by Reclaim Finance, pitting exclusion and engagement against each other can serve to paint these strategies as mutually exclusive. More problematic is the front that this framing of “engagement” can serve for investing in companies that continue to expand and profit from oil and gas production, as is the case for SSGA.

UK location: 20 Churchill Place, Canary Wharf.

SSGA CEO: Yie-Hsin Hung

Yie-Hsin Hung has been the President & CEO of SSGA since December 2022. She was previously CEO of New York Life Investment Management (NYLIM), and worked at Bridgewater Associates and Morgan Stanley. Hung has been listed in American Banker’s “25 Most Powerful Women in Finance” for five years, and has recently been re-elected as Chair of the Executive Committee of the Investment Company Institute (ICI). The ICI is an investment association which has members that manage $37.8tn in assets (almost £30tn).

Ronald O’Hanley is Chairman and CEO of SSGA’s parent company, State Street Corporation, and previously occupied Hung’s position at SSGA. Last year, Hanley received a salary of $18m (£14m) – a 93% increase from 2020 to 2022. Putting this into perspective, the pay ratio between his annual compensation and the median compensation of all State Street Corporation’s employees for 2021 was estimated to be a staggering 230 to 1.

#7:SAFE Investment Company

#7:SAFE Investment Company

SAFE Investment Company Ltd. is one of China’s sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). It is the Hong Kong subsidiary of China’s foreign exchange regulator, the catchily-named State Administration of Foreign Exchange. Its ultimate parent is the country’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China.

Established in 1997, last year SAFE controlled nearly $1tn in assets, coming in just behind the China Investment Corporation (CIC), one of the world’s largest SWFs. China’s multiple SWFs were set up in the late nineties and early noughties as the government sought to increase engagement with international markets. Seeing an opportunity, SAFE began buying into major global firms during the 2007-8 financial crisis. Among the companies it began investing in at this time was BP; by 2008 it had upped its share in the company to a potential $2bn (£1.6bn).

Its shares in Shell and BP represent the company’s most valuable holdings, currently amounting to around £1.8bn and £1.2bn respectively. Besides these British oil giants, UK companies feature prominently among SAFE’s top public investments. These include pharmaceutical companies, AstraZeneca and GSK, and mining behemoths Anglo American and Rio Tinto. It invests in Yara, among the world’s largest producer of fertiliser (see Corporate Watch’s profile on Yara and its role in climate chaos here). These holdings are followed by a host of major Western brands, from Tesco and Lloyds Bank, to Burberry, Next, Whitbread and Compass Group.

It owns 0.47% of the UK’s National Grid – a holding currently worth £198m – and even has a stake in the London Stock Exchange.

SAFE’s largest shareholdings betray a particular interest in North Sea oil and gas, China being the world’s biggest importer of oil. It holds millions worth of shares in Subsea 7, an engineering firm servicing the offshore petrochemicals industry, notably North Sea oil. Subsea 7 is in turn is being awarded contracts by Norway’s state oil firm Equinor – which SAFE also has a stake in.

Despite having such a broad array of investments in global companies, like other sovereign wealth funds there is remarkably little publicly available information on SAFE. It does not publish information, at least in English, on any environmental standards.

UK location: Unclear if any.

Governor of the People’s Bank of China: Yi Gang

The management structure of SAFE Investment Co Ltd is not transparent. However, we know that the State Administration of Foreign Exchange is led by Pan Gongsheng, currently also Deputy Governor of its parent, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). He answers to former SAFE administrator, and current head of the PBoC, Yi Gang.

Yi Gang gained a Ph.D in Economics from the University of Illinois and later taught at Indiana University, Indianapolis, which he has referred to as his “second home”. Following his leadership at SAFE, he worked at the PBoC until he was appointed to the role of PBoC governor – the top management position – in 2018. He has just been re-appointed to the post for a second five-year term despite expectations to the contrary. Following an economic slowdown in China owing to strict COVID-19 lockdown measures, a weakening real estate market, and inflation hitting demand for Chinese goods abroad, this decision has been read as a bid by the Chinese state to maintain the appearance of stability.

But even a man described as “the most prominent Chinese figure in global finance”, is to some extent just a figurehead. He reportedly has no role in developing state monetary policy, as is the case in many other countries. Instead he implements the decisions of a “policymaking body whose membership is a secret”.

And as we can expect, any details on his interests, personal life, family connections and property remain well-hidden from public view.

#8: abrdn

#8: abrdn

abrdn plc, pronounced “Aberdeen”, is a multinational asset manager headquartered in Edinburgh. It provides investment services and financial advice to both institutions and individuals. Holding nearly £500bn of investments on behalf of its clients, it has been described as a “generalist” financial services firm, not specialising in any one form of investment.

It is one of the UK’s largest asset managers, and focuses on actively-managed investments, although it manages some passive funds as well. It employs over 5,000 people. abrdn is the rebranded name of Standard Life Aberdeen, which was created by the merger between Standard Life and Aberdeen Asset Management in 2017. The latest name change (“disemvoweling”, as it’s called) took effect in 2021 following the sale of assets and the Standard Life brand to UK-based pension fund Phoenix Group. abrdn and Phoenix have a complex strategic partnership, which includes abrdn managing around £147bn of Phoenix’s pension fund assets, making Phoenix abrdn’s largest client. abrdn and Phoenix Group have been fined over £7m and £35m respectively for investor protection and pension plan violations in the UK since 2010.

Since the merger, the company has been struggling with an identity crisis, declining share price, significant job cuts, and low staff morale which has been compounded by disquiet over the CEO’s “draconian” management style.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Claims vs Reality

abrdn’s environmental, social and governance messaging, which features prominently in company communications, has to win the prize for the most hypocritical and absurd. This is exemplified in its sustainability-themed partnership with the Financial Times, which includes content unironically offering to help spot corporate greenwashing, cautioning:

“As more consumers and investors embrace sustainability, companies are often tempted to exaggerate their social and environmental credentials.” In the same piece, abrdn suggests investors concerned about the environment could avoid selling shares in oil and gas companies, and even buy more of them.”

abrdn currently invests at least $5.7bn (£4.5bn) in oil, gas and thermal coal companies in the form of shares and bonds. Just over half of that total is invested in Shell and BP. abrdn previously rejected the call by “activist” hedge fund Third Point to break up Shell, in an apparent effort to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels. According abrdn’s latest filings, it also manages holdings of around £3.4bn in destructive mining companies, most notably, notorious conglomerates Glencore, Rio Tinto and Anglo American.

abrdn appears to have made urgent climate commitments as a signatory of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative (NZAM). However, the latest annual report reveals that only 30% of assets under management are within the scope of its carbon reduction targets. Reclaim Finance’s “Asset Managers Fuelling Climate Chaos” report offers a damning indictment of abrdn’s climate targets. It found no exclusion policies for investing in coal, oil or gas developers and allotted abrdn one of the worst ratings of the 30 firms under consideration with a score of just 1.3 out of a possible 30. abrdn in fact has significant investments in companies with plans to expand their fossil fuel operations. As of 2022, it held $900m (£713m) in bonds and $4.3bn (£3.4bn) in shares in these major carbon emitters.

In particular, the company is among the biggest bond holders in scandal-hit coal producer Adani. Adani reported to have invested £2.5bn in new coal mines in the last decade, whilst its coal output increased by 58% between 2021-2022. Its appalling track record has been extensively catalogued by campaigners against Adani in efforts to oppose coal mining activities in Australia. Corporate Watch has also reported on the threat to the environment and communities posed by its expansion in Australia’s Galilee Basin with Adani’s Carmichael coal mine. Whilst abrdn has declined to comment about its Adani bonds, it touts its membership of the “Powering Past Coal Alliance” and recognises coal to be the most carbon intensive fossil fuel. Perversely, abrdn selectively cites the potential impact on communities “reliant” on coal as a counter-consideration to the need to phase out its use, declaring its support for a “just transition”.

UK location : 1 George St, Edinburgh.

abrdn CEO: Stephen Bird

A Scot who started his career working in the steel industry, abrdn CEO Stephen Bird went on to enjoy a 20-year stint at Citigroup, most notably his role as CEO of consumer banking between 2015 and 2019. Citigroup have paid out huge fines, £282m and $26.6bn (£223m and £21bn) respectively, for regulatory violations in the UK since 2010 and the US since 2000. This includes nine-figure sums paid during the years that Bird was responsible for global consumer and commercial banking.

Bird joined abrdn’s board in July 2020 before becoming chief executive officer in September of that year, presiding over the much-ridiculed rebranding. More recently he has been the subject of an extensive exposé, based on the testimony of insiders, regarding allegations of aggressive and intimidating behaviour in his leadership of the company. These include him reportedly shouting “Are you a group of delinquent primary school children? This is a f***ing disgrace” at his colleagues during a discussion on voluntary redundancies.

His relationship with some of his co-workers has not been helped by his decision to award himself a £1.8m bonus, while cutting radically back on other staff bonuses. Since joining abrdn, Bird has been paid a total of £5.5m in compensation as chief executive officer and executive director. This is despite a continued decline in funds under management between 2020 and 2022 and the company briefly exiting the FTSE 100.