The corporate plunder of Strefi Hill

Since our interview with members of the Open Assembly for the Defence of Strefi Hill, Athens, the police repression has grown – but so has the resistance.

With a permanent deployment of approximately 150 police on the hill reported for the past half year, the atmosphere is intimidating, to say the least. Since August 2022 up until the time of writing, the assembly to defend the hill has reported constant harassment of those trying to use the park, including of kids coming to play basketball or simply hang out. It has counted over forty arrests in that time, as well as other acts of violence and tear gas used against local residents who refuse to back down in the face of state intimidation. Yet the assembly has sustained resistance in myriad forms – from demos, to intergenerational festivities with traditional dancing and choirs.

Strefi Hill is more than just an inner city park. It’s a precious gathering space at the heart of a spirited neighbourhood that successive governments have sought – but failed – to subdue and assimilate. It’s a haven for anarchists, refugees and other outsiders to organise or socialise, but also a valuable community space with an open theatre, basketball courts and a playground.

And it’s a refuge for wildlife too. Wild tortoises live on the hill, and the animal has become its symbol: ancient, free, and vulnerable – but ultimately tough in its weather-beaten shell.

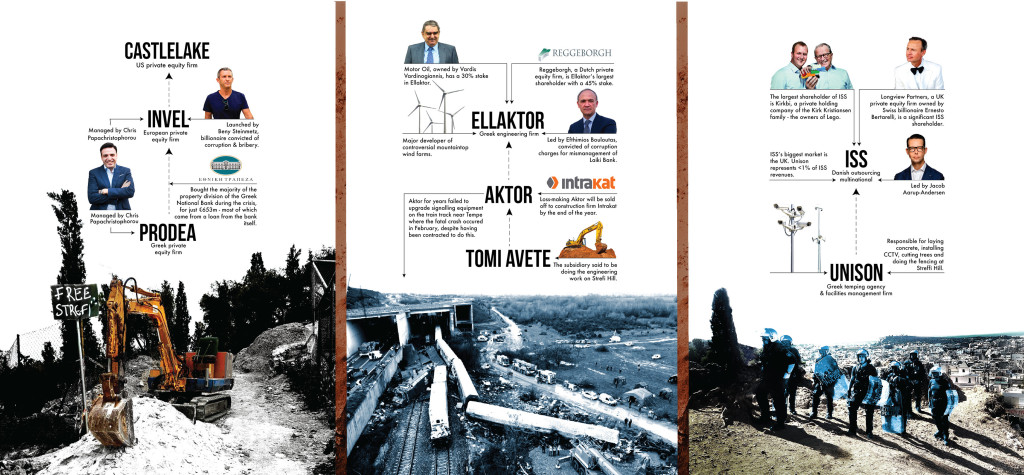

Since our interview, we’ve dug into the companies carving up this precious space for personal gain, hoping to inspire solidarity. We traced the financial interests back to faceless private equity firms in Northern Europe and the US – and found some wealthy Greek dynasties along the way.

The investors: PRODEA

Parent companies: Invel & Castlelake

€1m (£850k) in financing for the Strefi project is provided by Prodea, with €800,000 (£687k) supplied by Athens city council.

Prodea is a property developer listed on the Athens stock exchange. Its owner describes it as “the largest Real Estate Investment Company (“REIC”) in Greece in terms of assets”, and it has at least fifty subsidiaries – mostly based in Greece and Cyprus.

The majority of Prodea’s investments are in commercial property in the form of offices. Over a third of its portfolio is rented out to the National Bank of Greece, while 10% is leased to the Greek supermarket chain Sklavenitis. It is currently in discussions about participation in the controversial Elliniko megaproject on the site of Athens’ former airport, among the world’s biggest urban redevelopment schemes.

According to company accounts, the firm appears to be doing well financially. It made just over €98m (£84m) in profit in 2022, although this was a significant drop from the previous year’s profits of around €128m (£110m).

Prodea’s chairman and president is Christophoros “Chris” Papachristophorou, who is also managing partner of the parent company, Invel. Educated at the London School of Economics, Papachristophorou cut his teeth in the world of property as global head of RREEF Opportunistic Investments, a real estate investment manager then owned by Deutsche Bank. Several other former RREEF and Deutsche Bank real estate personnel populate the Invel and Prodea management teams. This includes Papachristophorou’s wife Marianna, a London Business School graduate who owns a £5m home in Chelsea.

In an indication of the company’s potential proximity to government, another Deutsche Bank alumni and recent Invel Partner, Alexis Pipilis, happens to be Facebook friends with Sofia Mitsotakis – daughter of the current Greek Prime Minister.

Invel

Prodea is owned by Invel, a Jersey-headquartered, multinational property investor and asset manager. The company specialises in “real estate and distressed debt opportunities across Europe”. It invites investment firms to contribute money alongside its own in the purchase of properties that are not considered to be profitable enough, and redevelops them.

Private Equity Explained

Private equity firms partner with wealthy individuals and institutions such as pension funds, and buy up companies to look for ways to make a return on their investment. These acquisitions are often supplemented by debt via loans from financial institutions. Money is made by charging investors a management fee, extracting a percentage of the profits generated by the businesses bought up and eventually, by selling them off.

They present themselves as providing expertise in both investment and corporate management. In reality that often translates into loading the company with debt used to finance its purchase, and 'restructuring': i.e. companies get cannibalised, job cuts are inflicted, workers’ pay and conditions are attacked. Where they become landlords through real estate deals, rents are raised on tenants. Private equity represents a process of ruthless, targeted extraction and exploitation for the benefit of the exclusive clientele able to participate. In short, "greed is good", in the words of the fictional PE corporate raider Gordon Gekko.

However, Invel’s most high-profile investment isn’t a luxury hotel or a chain of supermarkets – it’s the property division of the National Bank of Greece (NBG).

Back in the early 2010s, the institutional response to the Greek debt crisis was to provide loans on the condition of massive structural changes, such as the privatisation of public assets and the implementation of austerity measures. Consequently, the real estate subsidiary of the bailed-out National Bank of Greece, then known as Pangaea, was sold off to a consortium led by Invel—a company that had been in existence for less than a year.

And Invel got a bargain. It purchased a majority share for just €653m (£566m) – however €450m was paid for by a loan provided by the bank itself (at just 2.75% interest), meaning Invel only actually paid €203m (£174m) at the time. The deal initially gave Invel access to nearly €1bn in 252 properties; as the country emerged from the worst days of the crisis, the value has since multiplied to nearly €3bn (£2.6bn) euros in 380 properties. It acquired the remaining stake in the Pangaea in 2019, renaming the business Prodea.

The Steinmetz Connection

Crisis profiteering isn’t the only unsavoury aspect of Invel’s story. It would probably like to distance itself from its most inconvenient bedfellow, disgraced diamond merchant and Israel’s former richest citizen, Beny Steinmetz.

Beny Steinmetz launched Invel back in 2013 with $400m (£343m) start-up capital provided via his firm, BSG Real Estate, part of the convoluted Beny Steinmetz Group (BSG) business empire which spans minerals, fossil fuels, property and private equity. He hired Papachristophorou as Invel’s “man on the ground” in Greece and Cyprus, and was partner at the firm until his legal woes mounted five years later. Papachristophorou remains CEO of another company in that empire, BSG Resources.

In 2020, Steinmetz was convicted of “the creation of an organized criminal group” by a Romanian court, in a case concerning the bribery of public officials for access to real estate. He was sentenced to five years’ prison in absentia.

A year later, Steinmetz was convicted of bribery again – this time in a case involving tens of millions of dollars worth of payments to the wife of Guinea’s then dictator, Lansana Conté, in return for mining rights. The site concerned is one of the world’s largest known deposits of iron ore in Guinea’s Simandou mountain range, home to critically endangered Western chimpanzees. In 2008, Rio Tinto – which had been given exclusive rights to the mine (and still enjoys concessions in the project) – had its license revoked. Permits were instead granted to BSG Resources, a company with no history of iron ore mining.

Steinmetz and his associates spent years trying to shut down the story through aggressive PR and legal tactics, as well as (not having quite caught on the first time) further bribery attempts.

Then in May 2022, a World Bank arbitration panel ruled that the mining rights had indeed been obtained through bribery. Yet in spite of having been sentenced to a total of ten years in prison by courts in two jurisdictions, Steinmetz appears to be walking free while he appeals his second conviction.

Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert described Steinmetz as “the last guy you would want as an enemy”, and it no doubt helps to have family with access to power; his nephew was a partner in Jared Kushner’s property business, Kushner Companies. Steinmetz enjoys such a privileged relationship with Greece that despite the mounting evidence of corruption, a court in Athens rejected a Romanian extradition request in April 2022. He said he was “grateful to Greek justice” for this intervention.

A second figure who has been embroiled in the scandal is Shimon Menahem, another of Steinmetz’s nephews (in this case, by marriage), who invested heavily in Invel. In 2014, a Greek financial regulator noted that Papachristophorou and Menahem jointly controlled numerous companies, including exercising indirect joint control of at least one of Invel’s entities.

This map provides only a snapshot of Steinmetz’ nebulous corporate network, and many of his firms – as well as Invel’s extraordinary list of companies – are based in the tax havens Jersey, Guernsey and Luxembourg. Capitalism thrives on ambiguous corporate structures, and Steinmetz’ ability to evade the criminal justice system so far is testament to that.

Castlelake steps in

Following Steinmetz’s fall from grace, global investment firm Castlelake L.P. came to the rescue, acquiring significant shares in several Invel firms. Castlelake is now therefore the ultimate owner of Prodea, while Invel’s role in the relationship is that of a shell company – basically, a vehicle to run Prodea.

Castlelake is a multinational private equity firm specialising in planes and property. Although based in the US, the firm manages $20bn (£17bn) in assets through various funds – most of which are invested in Europe, according to financial databases.

It is headed by the founders, Rory O’Neill and Evan Carruthers. Both of them previously worked at the agribusiness conglomerate – and world’s largest private company – Cargill.

Engineers: Aktor

Parent company: Ellaktor

The engineering work on the hill is being carried out by Aktor. According to members of the assembly, this is being done via TOMI AVETE, an Aktor subsidiary specialising in urban developments.

Aktor is owned by Ellaktor, a major Greek construction and engineering conglomerate which operates in over thirty countries, notably in Eastern Europe and the Gulf. It works in construction, quarrying and property development, as well as building and running wind farms and wastewater treatment plants. The Group as a whole has benefited significantly from prominent public-private development projects for decades. It was, until a few years ago, led by two warring families, the Kallitsantsis clan, and the powerful Bobolas dynasty – which also owned controlling stakes in leading Greek media outlets. It is now headed by banker and private equity trader, Efthymios Bouloutas, who was convicted of corruption charges in 2018 associated with (mis)management of the now-defunct Laiki Bank. He evaded prison, walking away with a small fine.

Ellaktor has been called Greece’s second-largest producer of wind energy, running a dozen or so such farms, and now branching out into offshore wind power. Wind energy has been particularly controversial in Greece over the past couple of years, with deregulation resulting in farms being plonked on mountain tops in ecologically-sensitive habitats, and communities mobilising against the developments. Aktor also had a 5% stake in the gold mine at Skouries, Northern Greece, until this was bought by Eldorado Gold in 2020. Locals and supporters have mounted a decades-long, historic campaign of resistance to the ecologically-disastrous plan, and the mine is still not yet in production.

Returning to the present day, Aktor is one of several companies implicated in February’s catastrophic train collision near Tempe, Greece’s deadliest rail disaster. In 2014, Aktor was awarded the contract to upgrade the signalling system on approximately 500km of the Athens-Thessaloniki line, in a joint venture with French rail giant Alstom. But a recent report by Reporters United and Investigate Europe found that the two companies repeatedly failed to carry out their duties, and instead spent years bickering and demanding a larger contract. This was eventually approved in 2021 for an extra €13m (£11m). However, despite having been given more money, the companies were apparently still unable to get along. This led to Aktor subcontracting everything to Alstom, which had begun the work by the time of the crash.

Greek Prime Minister Mitsotakis has attributed the disaster, which killed at least 57 people, to “tragic human error”; industry experts have said that an adequate signalling system would have prevented the accident from happening.

Neither trains nor joint ventures seem to be the company’s forte. Aktor was part of another joint venture that was awarded a multi-billion euro contract to extend the Doha metro. The consortium become embroiled in a dispute with a subcontractor, which took it to court resulting in a $98.5m (£79m) fine. Aktor had to pay a substantial share of the damages.

Despite its record, Ellaktor has bid to lead the consortium that would run the new Thessaloniki metro, once completed. It has been involved in the construction of the network, although the work has been hampered by delays for years, and the company again ran into dispute with a contractor.

Protracted construction projects have resulted in a significant backlog and debt for Aktor, and it made losses of €155.5m (£133m) in 2020. Despite it being the Group’s largest company, it is now being sold off to major competitor Intrakat for €100m, in a deal expected to be completed before the end of the year.

Today, Dutch private equity firm Reggeborgh is Ellaktor’s largest shareholder, with a total stake of approximately 45%. Until recently, it also had a large shareholding in another major Greek construction firm, GEK Terna. Reggeborgh has been described as the investment vehicle of the Dutch Wessels family, which is behind the conglomerate VolkerWessels.

The next largest shareholder (with roughly 30%) is Motor Oil, a Greek petrochemicals firm chaired by billionaire shipping tycoon Vardis Vardinogiannis.

The managers: UNISON

Parent company: ISS

According to the Open Assembly for the Defence of Strefi Hill, the installation of the CCTV cameras, tree-cutting, fencing, concreting and cleaning has been contracted to a Greek firm called Unison.

Unison describes itself as Greece’s “market leader in the facility management industry”. Set up in the late seventies as ISS Group Hellas, it was rebranded in 2021.

Unison carries out much of the same work as its parent company, the global outsourcing giant ISS. It also has a human resources subsidiary specialising in temping work, and says that it is the first company in Greece to have received a temping license.

ISS

Danish outsourcer ISS has its roots in the security business in the early 20th century, before it branched out into cleaning, catering, site and equipment maintenance. It is now a facilities management multinational, smaller than the behemoths Sodexho and Compass Group, but larger than the British outsourcing firm Mitie. It is led by CEO Jacob Aarup-Andersen, an investment banker.

Unison represents particularly marginal revenues for ISS, at less than 1% – and isn’t even included in ISS’s list of significant subsidiaries. ISS’s most important market is the UK, where the majority (15%) of its global income is generated. It is headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark.

ISS is a publicly-traded company. Kirkbi A/S, a private holding of the Danish Kirk Kristiansen family (owner of the world’s most profitable toy company, Lego), has a 17% shareholding in the business.

British-based private equity firm Longview Partners has a smaller (7%) shareholding. Ownership of Longview can be traced back to Ernesto Bertarelli, Swiss billionaire and until recently, Switzerland’s richest person. Bertarelli recently bought a £92m home in Belgravia, London using wealth which ultimately derives from his family’s former pharmaceutical business.

Conclusion

Tugging on the threads of Strefi Hill unravels a patchwork of companies and individuals united in self-interest and corporate greed, from faceless US investors and a corrupt Israeli diamond merchant, to an LSE-educated banker and a Swiss billionaire. The cases of Aktor and Steinmetz show how proximity to power means they can keep getting the contracts, no matter how corrupt or incompetent they may be.

These corporate interests can be traced far beyond Athens, with wealth being funnelled back to countries such as the UK, Switzerland, Netherlands, Denmark and the US. The attack on the hill is part of a global struggle against the suppression of dissent, alternative lifestyles and free public spaces. But with collective resistance and solidarity, victory against the devastating forces of gentrification is within reach.

Appendix: Addresses

See the links for more locations

Athens: Chrisospiliotissis 9, 105 60.

- InvelAthens: (same as Prodea) Chrisospiliotissis 9, 105 60.London: 1st Floor, 26 Grosvenor Gardens, London, SW1W 0GT.(See the link for more)

London: 15 Sackville Street, W1S 3DJ.

Athens: Andrea Siggrou 194, Kallithea 176 71.

UK: 1 Brooklands Drive Brooklands, Weybridge, Surrey, KT13 0SL

Athens: Ermou 25, Kifisia 145 64.

Aktor: As Ellaktor