The National Wealth Service: Privatisation Profiteers

This is the first in a series of three articles investigating the accelerated privatisation of our NHS for private healthcare profits. Part two examines the litany of scandals and the key players in the five companies we researched. The third article is a timeline detailing NHS privatisation since its formation in 1948.

For decades, successive Labour and Conservative governments and private healthcare giants have carved up the NHS for profit. Now, it’s on its knees. Acute staff shortages, crumbling infrastructure and outdated equipment have all contributed to a system that currently has more than 7.7 million patients waiting for treatment in England alone. Exhausted and desperate, nurses, ambulance staff, junior doctors and consultants have had no option but to strike in protest against plummeting wages and rock-bottom morale.

The pandemic created a perfect storm for politicians to sell the lie that private healthcare companies help relieve pressure on public services. In December 2022, the government launched its post-pandemic Elective Recovery Taskforce which effectively ‘turbo-charged’ private healthcare capacity to put NHS privatisation on full acceleration.

Knowing that vast profits are coming in for private healthcare, Corporate Watch, in collaboration with Good Jobs First, – a US-based non-profit which maintains databases tracking regulatory violations and penalties in the US and the UK – set out to investigate the extent of contracts awarded to just five profiteers: Bridgepoint, BUPA, Centene Corporation, Spire Healthcare and UnitedHealth Group (UHG). We targeted these companies because all five are members of the Independent Healthcare Providers’ Network, made up of CEOs and leading industry lobbyists. The CEOs of three of them met with Rishi Sunak at the launch of the Elective Recovery Taskforce which appointed the Network CEO.

As it seemed that no one had yet conducted a deep dive into existing contracts for these five companies and their subsidiaries, Corporate Watch wanted to find out what has already been paid. We examined all the health and social care contracts these five companies have won and hope to shed light on how much public money has been awarded despite their regulatory misconduct and scandal-hit records (explored in Part Two of this investigation). In the process of collating records of these public sector contracts, serious questions also emerged about the opacity of reporting contracts, as well as the integrity and reliability of the data made publicly available.

Among other things, we found:

- Over the past ten years, these five companies have won a share of contracts worth at least £70.59bn, though the lack of available data means the exact amount awarded to each firm remains unknown.

- The length of contracts awarded appears to be increasing over time, as the Conservatives have sought to ‘lock in’ privatisation going into the future.

- Though the government may be planning for the long-term, the perspective among these firms appears anything but, with their rapid rate of buying and selling healthcare assets that appears to prize short-term profit over stable and sustainable services.

Billions of pounds in health and social care contracts

Between 2013 and mid-2023, Bridgepoint, BUPA, Centene, Spire and UHG won a share of public health and social care contracts with a minimum reported value of £70.59bn. More shocking still, an enormous £61.87bn of that total has been awarded without a clear breakdown of how much money each of the winning bidders was paid.

Our research revealed that £53bn was concentrated in nine of the 740 contracts that Corporate Watch accessed. £20bn of public money was committed in one single deal (see below). Just over a fifth of contract award notifications we found didn’t even report a total value, meaning the true figures could be far higher. Despite gaps in available data, our research found that Bridgepoint, BUPA, Centene Corporation, Spire Healthcare and UHG have won contracts worth at least £4.6bn.

Alarmingly, the length of contracts can now exceed a decade, and some are set to run for as long as 15 years. This serves to ‘lock in’ the privatisation of NHS services.

The five companies

The key companies and their subsidiaries targeted as part of this investigation are:

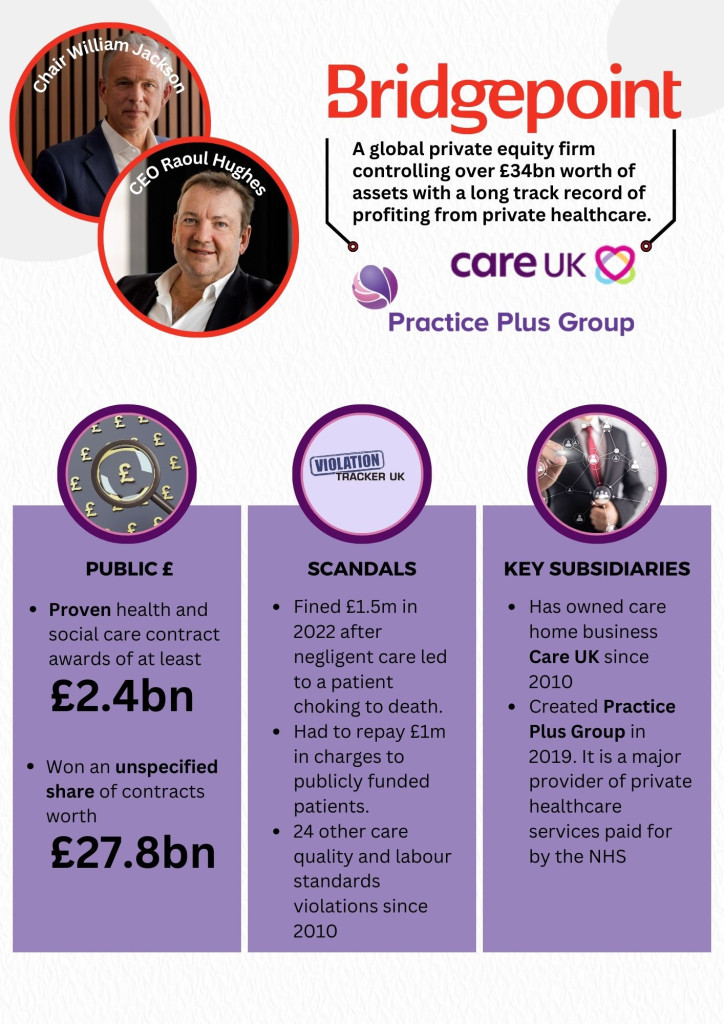

Bridgepoint is a multinational private equity business with over €39.5bn (over £34bn) in assets under management. It has owned Care UK since 2010 and created Practice Plus Group, now the largest private healthcare provider of NHS services when it divided care home and other healthcare interests following a 2019 restructure. Proven worth of healthcare contracts: £2.4bn, in addition to a share of contracts worth £27.8bn.

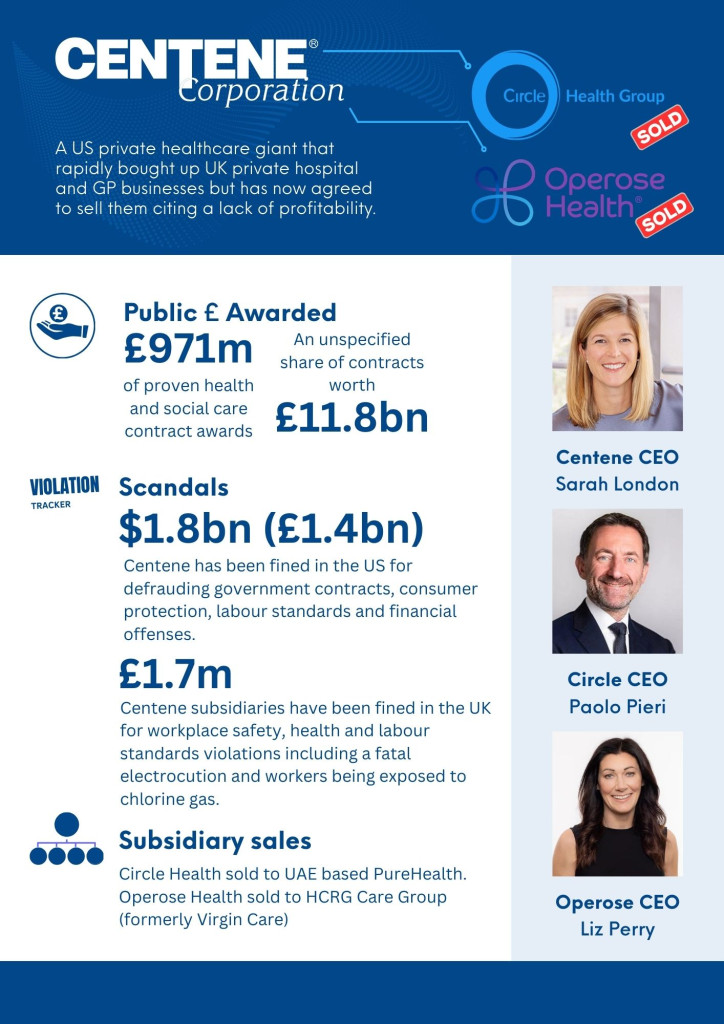

Centene Corporation is a private healthcare behemoth headquartered in the US. In 2023 it was ranked the 25th largest company in the US with revenues of $145.5bn (£114.3bn), driven significantly by US government-contracted health provision like Medicaid and Medicare. It has undertaken rapid expansion in the UK in recent years, owning the largest private hospital network (Circle Health) and provider of primary care (Operose Health). Proven worth of healthcare contracts: £971m, in addition to a share of contracts worth £11.8bn.

Spire Healthcare a publicly traded private company which operates 39 hospitals and eight clinics in the UK. It also owns 23 private GP practices following the purchase of The Doctors Clinic Group in 2022, and is one of the largest private hospital operators in the UK. Proven worth of healthcare contracts: £590m, in addition to a share of contracts worth £10.4bn

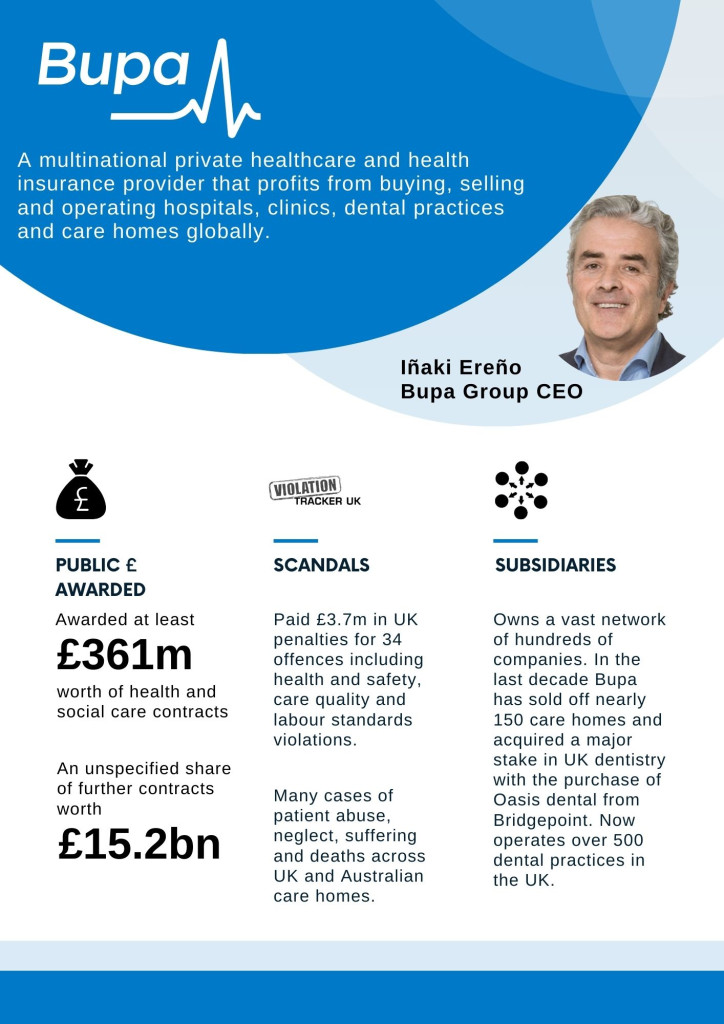

British United Provident Association Limited (BUPA) is a British multinational private healthcare and health insurance provider. It operates hospitals globally, care homes in a number of countries and also profits from its dentistry business in the UK. Proven worth of healthcare contracts: £361m, in addition to a share of contracts worth £15.2bn

UnitedHealth Group Incorporated (UHG) is a US-headquartered multinational managed healthcare and health insurance provider. It earned $324bn (£254.7bn) in 2022 making it the 10th largest company in the US by revenue, and has since focused on NHS commissioning opportunities created by the 2012 reforms via its subsidiary Optum, itself in the process of acquiring UK healthcare data company EMIS Group for £1.24bn. EMIS is a leading company for electronic patient records and software (see below) and will add hundreds of millions of public sector contract revenue to UHG’s tally. Proven worth of healthcare contracts: 309m, in addition to a share of contracts worth: £30.7bn

An acute lack of transparency

Across the data we gathered, Corporate Watch uncovered several glaring irregularities. Of the 740 contracts won by Bridgepoint, BUPA, Centene, Spire, UHG or their subsidiaries, 155 listed no total value (£0), meaning there is no reporting on the value of the actual contract . Some of these contracts list low and high bids from suppliers, but there is no breakdown of or attribution to those bids, nor an indication of which were successful, although they can give an idea of what the contract might be worth.

One of these £0 deals – a 2015 agreement designed to further open up NHS decision making on spending to private sector influence, with a number of suppliers including UHG’s Optum – records low and high bids of between £3bn and £5bn. Such a significant contract surely merits clear and detailed reporting. Contracts for £0.01 appear frequently across the data we analysed, demonstrating just how opaque the company reports of these government-awarded contracts are.

For example, one 2016 agreement which included EMIS Group subsidiaries EMIS Health and Ascribe Ltd for patient record software and other digital services did not report an exact total value but listed bids for individual lots between £0.01 and £130m.

In 2019, the NHS Supply Chain created a framework agreement with an initial list of 34 suppliers, including Bridgepoint’s Care UK and BMI Healthcare (now part of Centene’s Circle Health), for mobile and strategic clinical solutions. While being reported with a £0 value, the contract stated an anticipated cost of between £250m to £600m over its four-year duration, but there are no subsequent documents stating how much was actually paid out and to whom.

There are also contracts listed for what seem to be ‘placeholder’ sums of £1, such as the 2018 agreement struck by the London Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) with 97 providers including Bridgepoint’s Care UK and one of BUPA’s care home subsidiaries for a range of healthcare services in nursing homes. Given this is a pan-London contract and given the size of the capital’s population, what was the actual cost of this agreement?

Another contract involving London CCGs was a £58.6m deal split into two lots for 111 call handling, clinical assessment and out of hours GP services in 2020. The London Ambulance Service was assigned £27.5m as the contractor for the first lot covering 111 call handling with a subcontracting arrangement with Bridgepoint’s Practice Plus Group reported with a £1 placeholder value. Practice Plus Group was one of the contractors for the second lot covering clinical assessments and out of hours GP services. Although the contract references the value of the second lot as £31m, the contractor arrangements were recorded as just £1. This is a convoluted arrangement, and the sums involved seem to open up valid questions about the contracts going out to private healthcare giants.

Many of the contracts without a total value, or where it was recorded as £0/£1, didn’t even detail bidding information so there’s no way to know from the public reports what the estimated, budgeted or agreed costs were. These examples give an indication of just how much spending commitment may be concealed behind this secretive reporting.

Using public money to prop up the private sector during the pandemic

The government’s use of the pandemic to pump public money into private healthcare is exemplified by a £20bn contract for pathology services awarded to a number of companies including UHG’s subsidiary Change Healthcare UK Ltd. The value of an initial deal for £763m made by the NHS Supply Chain with private companies in 2019, had its value dramatically revised upwards the following year. The contract notes this is a “high-end estimation” due to the “pandemic situation.” This enormous contract appears to have received little examination and no further notices detailing how much of the £20bn has been spent have been issued. The government’s “framework agreements” appear to commit vast sums to private healthcare providers with minimal details published for public scrutiny.

Further eye-watering examples in our dataset include two £10bn deals struck by the NHS Commissioning Board during the pandemic. The first of these was agreed in 2020 under the guise of increasing NHS capacity with Bridgepoint’s Practice Plus Group, Centene-owned Circle Health and Operose Health, Spire Healthcare and BUPA’s Medical Services International Limited winning unspecified shares of the contract. The following year a further £10bn was committed to a framework agreement for supplying community diagnostic hubs. Once again, while the names of awarded suppliers, like Bridgepoint’s Practice Plus Group, were published, there was no indication of how much they stood to earn from the contract. These deals include “estimated” spends which can evidently be increased dramatically with little to no oversight.

Whilst huge sums of public money have been committed to the private sector since the pandemic began, evidence shows it has failed to deliver. Research by the Centre for Health in the Public Interest exposed chronic under-utilisation of the private sector capacity block-purchased by the government from March 2020 onwards. It appears the deals benefited private providers, more than the NHS or the patients who rely on it. In the end, only a measly 0.08% of covid patients were treated under the deal with the private sector to undergo routine operations. Financial commitments to the private sector from the public purse served to underwrite their operating costs and provided them with assured income, yet the backlog of NHS waiting lists was never cleared and continues to rise. Without this intervention, would these private companies have survived the pandemic financially? This trend of private sector capacity failure has continued beyond the initial years of the pandemic. NHS statistics show that the vast majority of procedures are carried out by the NHS directly, with the private sector continuing to play a minor role.

The financialisaton of healthcare

Multinational private healthcare providers operate complex webs of subsidiaries and holding companies through mergers, acquisitions, divestments, and restructurings. Global horse-trading of UK private healthcare assets, increasingly dependent on public contracts, seems to be turning into a financial carousel. Companies routinely acquire and offload “assets”. Monopolies emerge in a scramble for prime positions to extract profit and deliver returns to shareholders, which are then sold on for even greater profit. We found numerous examples of this practice in the five companies we investigated.

EMIS Group: a big fish being swallowed by a whale

The marketisation of healthcare was sold as a means to ensure competition between companies that would ensure we, the patients, could access the best treatment. Yet, UHG’s acquisition of the EMIS Group epitomises the sham of this NHS “marketisation” ideology that increasingly leads towards monopolisation by private healthcare companies. A “market leader” in patient records, appointment booking and prescription management software, EMIS Group sells software used by 58% of GP practices (approx. 3,787). Dependence on EMIS was brought into stark relief in May 2023 when GPs couldn’t provide any patient services following a catastrophic IT outage. Such is the extent of reliance on EMIS, contract awards note that practices couldn’t function if they were locked in to this contract and it was not extended or renewed.

The £1.24bn acquisition of EMIS by US healthcare giant UHG has now been waived through by the Competition Markets Authority (CMA). UHG clearly recognises the value of the critical position EMIS Group has established under the privatisation regime. It has won contracts worth at least £241m and was the sole provider awarded on £226m of that total. The largest of these deals was £137m, agreed back in 2014 but was only published in 2018 by the Department of Health. A string of contract awards reveals that EMIS is, unsurprisingly, deemed the only suitable bidder to support and operate its own software. We also observed the farce of EMIS being the sole bidder on open tenders. Several contracts recorded low and high bids from the EMIS group and on one of those contracts the high bid also recorded as the estimated cost of the contract. It has won numerous extensions and was awarded contracts which could run for as long as 10 years. Taken together, this demonstrates the advantages global healthcare giants can reap in the monopolistic model of privatisation that has been imposed on the NHS.

Alongside those contracts with actual information about precise amounts awarded, EMIS won a share of a £5bn contract providing Clinical Digital Solutions (CDS) for the Integrated Health Economy Framework by NHS London Procurement Partnership. Also listed among the successful bidders were its new owners (UHG) via its ominously named subsidiary Change Healthcare UK. There are also serious questions about conflicts of interest arising from the deal because of the role that Optum, UHGs UK subsidiary, plays in NHS commissioning support.

Centene cuts and runs

Between 2019 and 2021 Centene invested in, and finally took full ownership of Circle Health, which became the UK’s largest private hospital operator after also buying up BMI Healthcare. Centene is now cashing in on Circle Health, having agreed to sell it to United Arab Emirates based PureHealth for $1.2bn (£940m). It has also struck a deal for the sale of Operose Health to HCRG Care Group, formerly Virgin Care, for an undisclosed sum. This sudden exit from UK healthcare is apparently due to a lack of profitability. Centene cited a failure to incentivise GPs to refer patients to its Circle hospitals. This is another example of the brazen conflicts of interest that arise from private sector involvement in public healthcare provision. Patients, including the 640,000 who rely on Operose Health’s GP surgeries, now face an uncertain future with no idea what plans the buyers have for the services. The cross-party agenda to direct public spending towards the private healthcare sector heightens concerns about this unreliability. Profiteering and the influence of private equity in healthcare make for an unstable landscape and healthcare services.

Healthcare horsetrading

- Bridgepoint acquired Oasis Dental in 2013 before selling it on for quadruple the price to BUPA just three years later.

- BUPA's hospitals had been bought by private equity group Cinven, one of a number of deals it struck whilst forming Spire Healthcare between 2007-8.

- Spire Healthcare became a publicly traded company when it was listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2014, with Cinven cashing in on its shares by the following year.

- In 2021, Australian private provider Ramsay Healthcare attempted a takeover of Spire. Amongst those opposed to the deal was Toscafund Asset Management, which increased its investment in Spire after selling its controlling stake in Circle Health to Centene Corporation for approximately £900m.

- Toscafund ended the model of employee ownership when it took over Circle Health in 2017. UHG sold its GP surgeries business to what is now Centene’s Operose Health in 2011.

- Centene became the largest primary care provider when Operose Health, itself created from a merger between the Practice Group and Simplify Health, acquired At Medics in 2021.

Locking in privatisation

The awards of increasingly lengthy contracts are a clear sign that the government is locking in privatisation of health and social care services. We found contracts for care services, orthodontics, GP surgeries and healthcare in prisons and immigration removal centres set to run for between seven and 15 years. Here are just a few examples:

- A 2019 contract between North East London (NEL) Commissioning Support Unit and 40 private providers including BUPA’s Oasis Dental worth £335m for the provision of Orthodontics that can run for 10 years (a seven year initial term with an option to extend for a further three).

- A contract agreed in 2019 between NHS England and private providers such as AT Medics, since taken over by Centene’s Operose Health, to run primary medical care services in London for up to 15 years. These contracts were awarded in tranches, with the seventh worth £226m and At Medics being awarded £121m of that total. Previous tranches five and six, agreed in 2017 and 2018 (also awarded to At Medics) were set to run for 10 years.

- Care UK, owned by Bridgepoint, won an unspecified share of a £53m contract securing a block of residential and nursing beds in Cambridgeshire in 2020 which could run for 15 years if all extensions are approved.

- Bridgepoint’s Practice Plus Group was awarded £42m by NHS England from a £278m contract to run for seven years providing health services in prisons in the south west in 2022.

- In 2022 Practice Plus Group won a contract worth £40m to provide healthcare services at Heathrow Immigration Removal Centres for seven years.

This development proves the real motives behind the so-called ‘marketisation’ of the NHS. The prospect of any actual competition between providers stands in stark contrast to the enormous advantages enjoyed by current providers, bolstered by the idea that attempting to replace them would bring huge upheaval. This argument, along with a move toward longer contract periods to supposedly ensure continuity and smooth provision of services, only entrenches a legacy system that prioritises private profit above the needs of publicly owned and operated public services.

Data diving

Collating this data required several research stages:

- We established the corporate structure of each of the target companies, and compiled a list of subsidiaries that operate in the UK.

- We then searched public data sources for contracts looking for the name of the parent company or subsidiaries as an awarded supplier.

- This key contract information was exported into a database.

- We then used this database to establish the value of the contracts – and how much was paid to subsidiaries – to calculate a total (for each parent company) showing how much public money they’ve been awarded.

- We also checked details of each contract award to avoid double counting, particularly for shared contracts.

Public records of contracts awarded to private companies proved at best labyrinthine and at worst unreliable. The contracts themselves are rarely made available, and those few that have been heavily redacted. Instead, a limited template summary of the agreement is posted on one of three data sources: Contracts Finder, Tenders Electronic Daily and Find a Tender, as a contract award notification.

These notifications should inform the public of the nature of the contract, its total value, amounts paid to awarded suppliers, the type of tender process and the length it is due to run including possible extensions and subcontracting arrangements. In practice, establishing the amount of public money paid to private companies for health and social care contracts via these sources was arduous. Even when the frame of reference is narrowed, as in this research project, to entities owned by five major private providers it took our team months of intensive work to build any kind of picture of the sums involved from the available datasets. This opacity seems to be a design feature of the publicly funded privatisation system: publishing contracts gives the appearance of transparency yet meaningful scrutiny is extremely difficult.

We also encountered myriad problems caused by unreliable data including:

- Missing information, with a fifth of contracts (155) recording no total value. In others, contractors are missing between issuances across and within different datasets and there is a lack of start/end dates.

- Missing details relating to the extension of contracts (in these cases the max amounts likely aren’t the max amounts, as we have no way of telling whether they were extended and under what terms).

- Inconsistent figures across different databases, and a lack of uniformity in the way data was presented, both across and within government sources.

Death by a thousand cuts

COVID-19 poured kerosene on a fire at the heart of the NHS, providing a ready-made excuse for the current Tory administration to accelerate a devastating policy of privatisation that stretches back over decades. As demand for private treatments slumped, for-profit healthcare providers effectively cashed in on a publicly funded government bailouts that available evidence suggests actually did little to benefit the NHS or its patients. Massive financial commitments have now been made either through the issuance of new awards or the inflation and extension of existing arrangements, fuelling the churn of acquisitions and divestments, as corporations and private equity firms across the sector build up their monopolies and turn profits in order to deliver their promised returns to their investors.

During this research, Corporate Watch uncovered tens of billions in financial commitments with little clarity as to the true value of awarded contracts. Though we can show how these firms hoovered up at least £4.4 billion via their myriad subsidiaries, the difficulties we encountered in collating the data mean their shares of some £61.87bn worth of government tenders remains unknown. Missing information, a paucity of detail and inconsistent figures and formats, to mention nothing of the lack of a single, centralised record-keeping system, has made tracking government spending in this area a truly monumental task.

The litany of scandals and regulatory violations outlined in Part Two of this investigation, raises serious questions about the government’s decision to entrust these companies with the provision of public health services and social care. These five are themselves just five among hundreds of other firms being awarded, with little competition, contracts across the NHS, as it is systematically sold-off for profit. The current broken state of the NHS is the inevitable result.