UK Border Regime: a brief history of resistance to immigration detention

This is an excerpt from our new book The UK Border Regime, coming soon. Also see our briefing here for background information on the UK detention system and the companies who profit from it.

Detention centres have always been amongst the most active sites of migrant struggle in the UK. Inside, resistance takes numerous forms: small everyday acts of refusal and solidarity, sit-in protests and hunger strikes, escapes, and sometimes major outbreaks of revolt. The most famous of these was the Yarl’s Wood uprising in 2002, which permanently destroyed half of the new centre just a few months after it opened.

On the outside, detainees’ struggles have been supported by numerous visitors’ networks, vital legal and medical support groups such as Bail for Immigration Detainees and Medical Justice, solidarity demos, and more. Recently, political campaigns have particularly focused on the introduction of a time limit. It is hard to assess the impact of reforming campaigns. What we are sure of is that solidarity from the outside plays a vital role in sustaining people struggling individually and collectively inside detention.

Campsfield in the 1990s

Some basic patterns of detention struggle are clear from the first few months of Campsfield’s history, as documented by the Campaign to Close Campsfield. In February 1994, three months after the centre opened, eleven mostly Algerian detainees started a hunger strike which was supported by demonstrations on the outside organised by the Algerian Community Association and others. All eleven won their release.

Then on 11 March 175 detainees started a mass hunger strike, which spread to 400 people in detention centres across the UK. On 12 March, detainees occupied Campsfield’s roof for the first time. The authorities came back hard, transferring nine of the occupiers to prison, and starting a wave of unannounced deportations of hunger strikers and other detainees.

On 4 June, 600 people held a solidarity demonstration outside the centre. Some stayed to form a “camp for human rights” outside the gates. The next day, 5 June, guards grabbed Ali Tamarat, a vocal former hunger striker who had been released then arrested and detained again, and took him to be deported. This sparked the first mass revolt. Detainees set fires and occupied rooftops, and eleven people managed to escape. Riot squads retook the centre, and 22 people were transferred to prison.

Protests, hunger strikes and riots continued at Campsfield throughout the 1990s. A revolt in 1997 led to the first case in which detainees were put on trial for rebelling – nine West African men were charged with “riot”. Supporters organised a significant solidarity campaign, and a solid legal defence team that exposed numerous examples of abuse and false testimony from Group 4 guards – the case was withdrawn by the prosecutor before the end of the trial.ii

The 2002 Yarl’s Wood revolt

As the new rash of centres opened from 2000, resistance grew rapidly as thousands more people were dragged into the detention system. Yarl’s Wood, opened November 2001, was the centrepiece in Labour’s expansion programme. It was designed to hold 900 people, far bigger than any other detention centre before or since. Security was outsourced to Group 4 (now part of G4S). Managers and guards were without experience in running this new kind of experimental facility, and detainees say that guards were particularly brutal and arrogant. Any complaints or protests were ignored and typically led to people being locked in their rooms. Anyone continuing to resist was sent to the segregation unit – this included people who had self-harmed or attempted suicide.

We’ll quote from Harmit Athwal’s summary of how the revolt began on the night of 14 February. This gives a taste of the petty disrespect of everyday life in detention, and of how people’s tolerance gets pushed to the limit.

it was the treatment by Group 4 officers of Eunice Edozieh, a 52-year-old Nigerian detainee called ‘Mama’ by other detainees, that sparked the disturbance. Eunice had been asking that day to see a doctor as she was suffering from haemorrhoids (and has now been diagnosed with an uterine prolapse). She became agitated and this was ‘dealt with’ by a supervisor distracting her by sending her a bogus message implying she had an outside phone call. DCO Suzanne Roadnight hearing one of Eunice’s requests to see a doctor told her to ‘Shut up and get out of my office’.

Later, Group 4 supervisor Gloria Bates and shift manager Alan Hughes decided that Eunice would not be allowed to attend church because of the ‘scene’ she had caused earlier. A notice was put up banning Eunice from church that night. Officers failed to tell Eunice of their decision, but when Eunice tried to attend church, she was refused access. Eunice became angry and upset and at least four Group 4 officers restrained her. […]

When other detainees caught sight of what was happening, they attempted to stop it and disorder broke out. In the ensuing mêlée, Group 4 staff lost control and fires broke out. Eunice and the female asylum seekers with her were then locked into the stairwell of the burning building […]

Group 4 ordered its guards to evacuate the building, leaving detainees locked inside. But not before some detainees had managed to take keys and free other prisoners. Prison service Tornado riot squads re-entered the centre at 2 am. By this time one half of the complex had burnt to the ground. The Home Office had decided not to install sprinklers. Thankfully, no bodies were found in the rubble. 23 people are believed to have escaped.

Eleven men, all asylum seekers, were put on trial for “violent disorder” and “affray”. Four were convicted, including two who pleaded guilty. But three were found not guilty by the jury, and four had their cases dismissed by the judge. In a common Home Office move, many key defence witnesses had been deported before the trial. All the acquitted defendants were re-arrested and put back in detention under immigration powers.

The destroyed half of Yarl’s Wood was never rebuilt. No doubt this was largely due to cost: the damage was estimated at £40 million. The Home Office also paid out to upgrade Harmondsworth and the remaining half of Yarl’s Wood with “millions of pounds worth of remedial investment”, while Colnbrook, which opened in 2004, was built “to a far more robust (concrete) specification”.iii

An official inquiry was commissioned, led by the Prisons Ombudsman Stephen Shaw. His report, published in 2004, recommended many new security procedures, as well as reforms such as improved food and medical care, cheaper phone calls and allowing detainees internet access. But it also found that the centre was simply too big for Group 4 to control. According to Shaw, the “decision to open an institution so much bigger than anything that had gone before” was the result of a rush to meet Jack Straw’s target for 4,000 detention places to facilitate 30,000 deportations (see The UK Border Regime: Chapter 1). As Shaw concluded in 2004, this target was “now accepted to have been unrealistic.”iv By then, too, the tabloid fever around asylum-seekers had died down, and with it the government’s urgency to expand the detention system.

Yarls’s Wood fire 2002

Later revolts

The next few years saw a number of other major revolts including at Harmondsworth in July 2004 and November 2006; and Campsfield in March 2007.

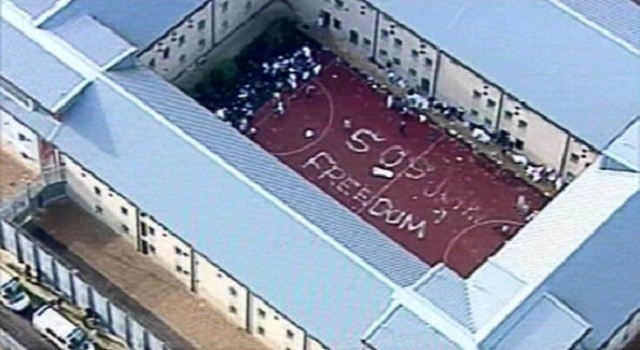

The 2006 Harmondsworth revolt began on the day the Chief Inspector of Prisons published what it called “undoubtedly the poorest report we have issued on an immigration removal centre”. That evening, after word of the report spread, people began breaking cameras and set fires. Kalyx (a subsidiary of Sodexo) security guards withdrew and called in the Tornado riot teams. Detainees gathered in a courtyard used sheets to spell out “SOS” and “Freedom” to the media helicopters buzzing overhead. All of the four people later charged with “violent disorder” were acquitted by the jury. Even the judge commented that “one might feel sympathy” with the detainees.

In the weeks after the Harmondsworth revolt, there were also riots in Oakington and Lindholme. Then in Campsfield, on 14 March 2007, inmates tried to stop “Control and Restraint” teams grabbing an Algerian man for deportation. The prisoner was taken, but riots and fires broke out.

Since 2007, there have certainly been many protests, and occasionally small riots, in UK detention centres. But there have been no revolts on the scale seen in 2002-7, and none have caused enough damage to put centres out of action.

Why is this? On the one hand, there is perhaps not the same level of pressure as in the mid-2000s, when the government’s rush to detain large numbers of people was at its height. On the other, the Home Office and its contractors have learnt lessons. Private sector detention managers and guards were inexperienced newcomers in 2002, but now this is a well-established business. The physical structures of detention centres have become more secure – and more fireproof. Brook House, Colnbrook, and Harmondsworth are effectively now Category B prisons. (This is the second highest of four security categories in the main prison system). As Stephen Shaw writes in his 2016 official review of the detention system:

It is relevant to the physical conditions in which detainees are now held that the early years of the century witnessed a number of serious disturbances, the most significant of which (Yarl’s Wood in 2002, Harmondsworth in 2004 and 2006) resulted in the near total destruction of the buildings.

And Shaw’s 2018 follow-up report adds that for any new detention centres: “what I do not think is in any doubt is that the houseblocks and perimeter security should be to category B standards.”

Harmondsworth 2006

The last ten years

The absence of major revolts does not mean struggle has gone away. Resistance is a constant of life in detention, taking many forms. Some notable recent examples include the struggle by women inside Yarl’s Wood who formed a Movement for Justice group in 2012, resisted deportations inside the centre, and held numerous protests and occupations. These actions were given considerable support by regular demos on the outside – by 2016 these were sometimes thousands strong.

Hunger strikes remain a major tactic of detainee resistance. In 2014 and again in 2015, mass hunger strikes spread through most of the UK’s detention centres. The Detained Voices website, set up in 2015, is an important resource broadcasting stories of resistance and calls for solidarity from inside detention.

It is hard to assess the impact of this continued resistance. Revolts which cause serious damage lead to official enquiries, recommendations and sometimes reforms. Hunger strikes and solidarity demos do not get the same public attention, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t have an impact behind the scenes. (It could be useful to make a thorough study of hunger strikes through the years, and see how and when they have been successful – unfortunately we haven’t had time to do that for this book).

The Home Office’s standard approach is, in public, to ignore all protests. But more experienced managers will try to see off struggles before they grow into a major threat. Sometimes this will mean stamping down hard – but other times quietly meeting people’s demands. (See the concluding chapter of The UK Border Regime for further discussion of the impacts of resistance and how the Home Office responds.)

Harmondsworth solidarity demo 2006

Campaigning on the outside

On the outside, there have been numerous groups and movements since the 1990s campaigning for detention closures and reforms.

Unfortunately, there are no successful examples of outside campaigns closing detention centres. The Campaign to Close Campsfield, started in 1993, has held monthly demos at the centre since it opened. Members say the campaign came close to succeeding in its first few years; it also helped win the acquittal of all nine West African prisoners accused of rioting in 1997.

It seems easier to stop centres being built or expanded than close them once they’re open. In 2015, campaigners stopped plans to expand Campsfield. According to someone involved:

It was a broad-based campaign mixing community organising, legal tactics, planning arguments (but not “Not In My Back Yard” (NIMBY) ones!), lobbying of local politicians and councils, and media-based campaigning. The straw that broke the camel’s back was the threat of legal action against the council for ignoring our argument that they should consider our principled case against detention as part of the planning decision, since the government had argued that the necessity for detention was a factor which made it possible to build on protected greenbelt land. When the council decided not to consider the planning application, the government withdrew it.

In 2017, the Stop Detention Scotland campaign stopped the opening of a new Short Term Holding Facility at Glasgow airport. Although there was an unintended consequence: the government kept Dungavel open instead. One person involved told us:

We did extensive research, consulted with the councillors who were to make the decision, created petitions and had the public submit hundreds of letters of objection to the planning committee. We went door to door around the community generating local resistance to the proposal and held protests at the council meeting and in Glasgow. The plan was unanimously rejected by the council and the Scottish National Party pledged that there would be no more detention centres in Scotland.

Recently, various detention campaign groups have united around the demand for a 28 day time limit. The present government is highly unlikely to budge on this, and a parliamentary amendment calling for a 60 day limit was soundly defeated in 2014.v

Things might change if Labour get elected. In May 2018, shadow home secretary Diane Abbot not only agreed with a 28 day limit, but talked of shutting Brook House and Yarl’s Wood (though not the others), and added that “private firms have no business in detention.”

But so far, it is fair to say that political campaigning against detention has not yet brought significant reverses at a national level. Recent falls in detention numbers have been due to government austerity cuts rather than any political shift.

The power of solidarity

On the other hand, we believe that solidarity campaigns from outside have given considerable strength to people inside, empowering both their personal and collective struggles. We know how much detention managers hate solidarity demos, because they fear how prisoners become fired up by feeling passionate support from without. And there are untold statements from prisoners themselves testifying to the power of solidarity across the walls. (Take a look at the Detained Voices website for some examples.)

It is also worth noting how many of the revolts mentioned above began with acts of solidarity between people inside: for example, other prisoners trying to help Ali Tamarat or Eunice Edozieh when they were attacked by guards. Both inside and outside, solidarity is central to resistance. Struggle comes alive when people feel they are not lone individuals isolated and crushed by the massive power of the system. When an attack on one is felt as an attack on all. These same patterns play out again and again in detention resistance – as they do in all prisons, and in our “prison society” on the outside too.

A manager told me last week that I should concentrate on my case and be more selfish as I might feel better if I stop taking on people’s problems. He might have a point but I can’t help but have empathy and maybe that’s why I could never do a job like his. I empathise with people regardless of the colour of their skin, sexual orientation, religious beliefs, and political beliefs. To me people are people, and we all want the same things on a human level. We want to feel safe, we want to love and be loved, and we want to feel accepted.

Detained Voices, 26 February 2018