The UK Border Regime: book introduction and summary

This is the introduction and summary from our new book The UK Border Regime, coming out very soon …

Throughout history, human beings have migrated. People move for many reasons: to escape war, oppression and poverty, to make a better life, to follow their own dreams. But since the start of the 20th century, modern governments have found ever more vicious ways to stop people moving freely.

The border regime is a name for the overall system that tries to control people’s ability to move and live, depending on our immigration status. That fixes our chances in life depending on what “papers” we have, on where we had the luck to be born, on our wealth or education, on the colour of our skin.

The UK border regime includes the state’s external borders, where people are checked coming through passport control, and patrol boats and sniffer dogs search for those trying to enter unseen. It also works inside the country, through the bureaucratic nightmare of visa and asylum applications, or the open violence of workplace raids, detention and deportation flights.

In recent years it has been creeping into ever more areas of everyday life: for example, “right to work” and “right to rent” rules, immigration checks in NHS hospitals, or the Schools Census collecting immigration data from children. This move has escalated with Theresa May’s “hostile environment” policy, but was already well under way with the previous Labour governments.

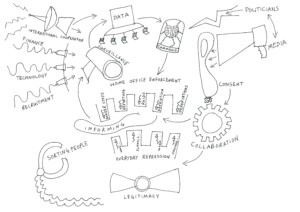

The Home Office is the main government department responsible for immigration control. But there are many other players involved too. For example, private security companies running detention centres, or IT firms developing new surveillance tools. Or the media pumping out anti-migrant propaganda, and ambitious politicians posturing to look “tough on immigration”.

And the border regime also relies on millions of other people collaborating in small ways, sometimes without even knowing. For example, healthcare or council workers, “just doing their jobs”, pass on personal information that may lead to someone being detained and deported. Or any of us who just walk on by when we see someone being stopped or raided. The border regime cannot exist without our consent.

What, and who, is this book for?

The aim of this book is to provide information and ideas to help understand how the border regime works, and to think about how we can fight it effectively.

Our research group, Corporate Watch, has been studying the UK border regime for ten years now. We have produced many articles and reports investigating parts of it, and in particular the private companies that make money from it. We work closely with people fighting the system, and are active in these struggles ourselves. In this book, for the first time, we bring this research together in one place.

The book isn’t about why the border regime is a problem. It says little about the human cost of borders – the deaths in the seas and deserts, the torture camps our government helps fund in Libya, the routine abuse and destitution faced by refugees who make it to the UK.

It is written for people who are angry about these things and want to stop them happening. For people directly affected by immigration controls, or those involved in groups fighting for free movement, or other people who support these struggles.

The book talks a little bit about how border controls are connected to other forms of oppression and exploitation – about the roles they play in capitalism, colonialism, nationalism and racism. We believe that the fight against borders is tied to struggles against all these structures, and more. But there is a lot more to say on this than can fit in this book.

One crucial point. Migrants, and above all people “without papers”, are on the cutting edge of this struggle. But the border regime affects all of us. The rich and powerful use it to spread fear and division, to stop people working together to make a world where everyone can live a decent life. As such, it can only be defeated with solidarity, by people both with and without papers fighting side by side.

What’s in this book (and what isn’t)?

This book contains:

- detailed profiles of different parts of the border regime and how they function, from databases and detention to media propaganda;

- information on border profiteers and their contracts, from security giants like G4S to data gatherers like Experian;

- some thoughts on how the system works together as a whole;

- examples of resistance over the last 20 years, looking at why actions have been effective, with a few thoughts on strategy.

We certainly don’t cover everything. Except for Calais, we don’t look much at the UK’s frontier controls. We don’t say much about how the UK works with the European Union to help build a “Fortress Europe” against Africa and Asia. There is lots more to investigate about how the UK, like other European states, tries to “externalise” its borders by making deals with ex-colonial countries. We barely scratch the surface of the connections between the border regime and the global economy. Also, at this point any comment on how Brexit will affect all this would just be speculation, so we say little about that.

All of these are crucial topics, but this book is pretty big and heavy as it is.

Summary

We have tried to divide the book up into self-contained sections so that you can skip to the parts you need. Here we’ll give a quick run-through of the main points of the book.

In addition, the final Annex to the book contains further information on border profiteers: a list of major Home Office contracts, and then mini-profiles of six companies. These are detention managers G4S, Mitie, Serco and GEO Group; plus deportation contractors Carlson Wagonlit Travel and Titan Airways. You can also find more detailed company profiles, and updates, on the Corporate Watch website.

Part One: Background

We start by looking at the history of the UK border regime. Attacks on migrants go back at least to the Middle Ages, but the idea of systematic border controls really kicked off with newspaper campaigns against Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe, which led to a 1905 law called the Aliens Act. More recently, the border regime has grown in three main phases, each involving both new laws and increased resources such as guards and detention centres. In each case we see a common pattern: media push scare stories targeting new scapegoat groups, politicians respond with clampdowns. In the 1970s, the targets were Black and Asian workers from Britain’s old empire; in the 2000s, asylum seekers from the wars in the Balkans and the Middle East; most recently, so-called “illegals”.

Chapter 2 takes a quick glimpse at the Home Office, its structures and resources. In Chapter 3, we look at how the border regime relies on identifying people and sorting us into categories: citizens vs. migrants, refugees vs. “economic migrants”, “genuine” vs. “bogus” asylum-seekers, “legal” vs. “illegal”. Some of these labels come from official definitions, such as the various “tiers” of the visa system, or the asylum process. Others are more informal. For example, there is actually no legal definition of an “illegal immigrant” – this label is the creation of newspapers and political speeches.

Chapter 4 looks a bit deeper at “what is the border regime”. This is the most theoretical bit of the book, introducing the idea of a system of control. To make the theory more real, we illustrate it with a diagram: a picture of a kind of Frankenstein’s Monster. The border regime is a monster, it has teeth and does real harm to people’s lives. But it is not unstoppable. It is made up of many parts, many of which are weak or rusty, many of which don’t work well together. When we can identify its joints and weak points, we can see where it is vulnerable and can be beaten.

Part Two: Control

This is the biggest part of the book, with nine chapters. The first seven look in detail at different parts of the border regime. These are:

- In limbo: the reporting and asylum dispersal systems.

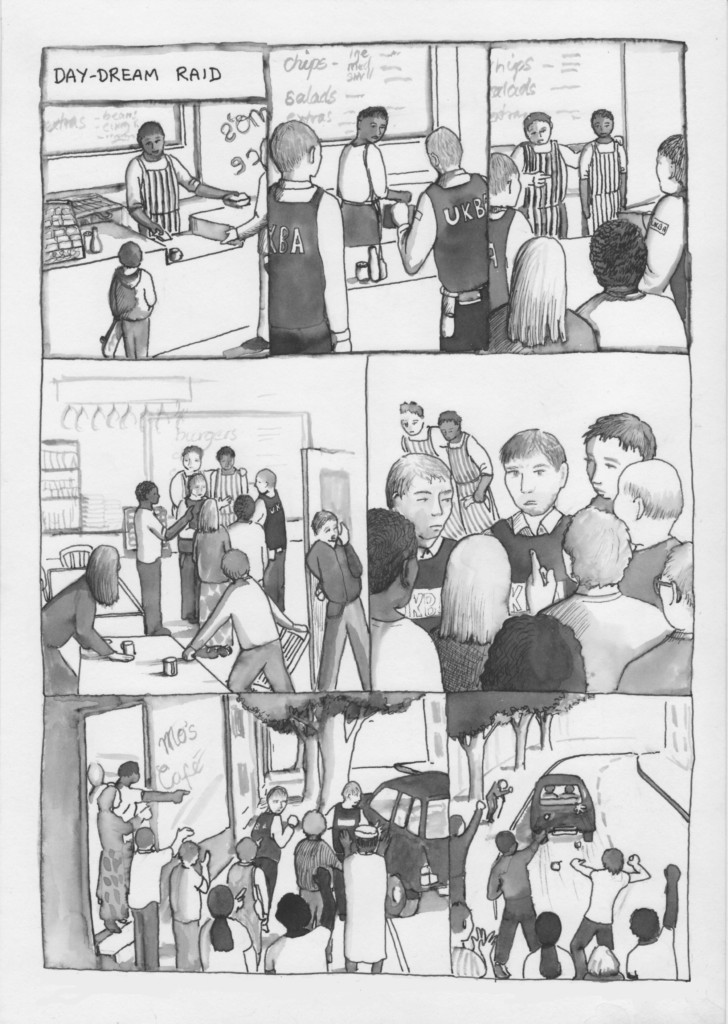

- Raids: the work of the 19 Immigration Enforcement raid squads, looking particularly at workplace raids.

- Detention: an overview of the immigration detention system and the private companies that run most of them.

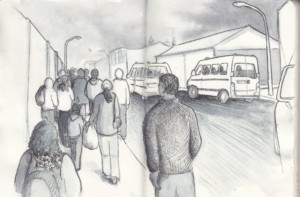

- Deportations: the “removal” system, with a particular focus on mass deportations using charter flights.

- Calais: the ultimate hostile environment on the UK-France border.

- Hostile Environment: a run-through of 12 main anti-migrant measures introduced under Theresa May’s recent hostile environment approach.

- Hostile data: how the Home Office tracks people with its current databases – and how it wants to expand them into One Big Datasphere.

In each chapter, we also look at how people are fighting back – and at the impacts of this resistance. From the revolts that forced the government to scale down its detention plans, and the countless cases of people beating deportations, to the legal and political battles that have ended charter flight routes and blocked or delayed recent hostile environment policies.

Chapter 12 looks deeper at how the border regime relies on the collaboration of many people outside the Home Office, from landlords and banks to nurses and teachers. It investigates the different ways the government tries to persuade people to collaborate. For example, not just threatening fines and prison sentences, but also seeking to shift the culture inside institutions like the NHS.

In Chapter 13 we ask: so what do all these attacks on migrants actually achieve? The border regime certainly makes many people’s lives a misery. But it doesn’t come close to achieving the official goal of “controlling immigration”. Since the 2000s, many policies have been based on the deterrent dogma: the idea that tough measures will persuade people to leave the UK, or not come in the first place. But the evidence suggests this doesn’t work. Indeed, the government’s own figures show “voluntary returns” have been going down since the start of the new hostile environment approach. The one factor that has actually affected immigration numbers is not a Home Office policy, but the Brexit vote scaring off investment and European workers.

In fact, we argue, the border regime will never succeed in effectively controlling immigration. At least, not so long as the UK remains a democratic state with limits on the use of visible violence, and a capitalist economy that demands migrant labour. This leads us to the question: so what are tough immigration policies really for?

Part Three: Consent

This part of the book digs a level deeper, to look at the forces that drive the border regime.

We suggest that hostile policies aren’t really about controlling immigration. They are shows, spectacles that “strike a pose” of control. Whipped up by media campaigns, politicians use new laws and clampdowns to pose at being tough.

Who is the show for? Politicians, from both left and right, often say they have to be tough on immigration to satisfy “public opinion”. But what does that actually mean? There is no one public opinion about migration: there are millions of different people, with very different views.

In Chapter 14, we look at the evidence from polling surveys on British people’s attitudes. In particular, an anxious minority of about 20% of the population say immigration is an important political issue. These are largely older, white people. Some are well-off pensioners living far from any actual immigrants. Others are working class people living in deprived areas, including the dispersal zones where asylum seekers are dumped. Crucially, both these demographic groupings are often key voters chased by politicians in election battles. They are the main target audiences for anti-immigration policies.

These target publics have quite different economic situations and experiences, but they share a sense of alienation and anxiety that is pumped up by media propaganda. Chapter 15 looks at how that works. Summarising several valuable studies, we see how media spread the story of migration as a threat – although specific scapegoats shift over the years. And we ask what motivates journalists and media bosses to do this dirty work.

Chapter 16 turns to politicians. We start with election strategy, seeing how politicians court target voter groups. Next we see how a run of Home Office ministers have built their careers posturing as tough on migrants. Finally, we look at how politicians exist in a closed bubble or “ecology of ideas” with the media – the two feed off each other in a vicious spiralling of bad ideas.

Chapter 17 gets to business. Some capitalists directly profit from the border regime. But most, from farmers to the City banks, rely on a constant supply of migrant labour. All major business lobby groups are pro-migration (in this narrow sense). This is why immigration policies never really try to close the borders to all migrants. Instead, policies target smaller scapegoat groups such as asylum seekers or “illegals”, who are seen as economically “low value”.

Chapter 18 looks at right-wing agitators. Far right parties, more respectable think-tanks like Migration Watch, and the new “alt-right” or “alt-light” internet propagandists, all work to push mainstream politics further against migrants. (Shifting the “Overton window” of what is politically acceptable.) Currently only about 20% of the UK population is strongly anti-migrant. But if these people have their way, the hatred will grow.

Finally, Chapter 19 digs deeper into the nature of anti-migrant propaganda. It is rooted in fear, part of the politics of anxiety that shapes many aspects of our culture today. What does this mean for those who want to fight these ideas?

Part 4: Fighting Back

People are fighting the border regime every day – and winning. Yet there’s no denying we’re swimming against a strong tide. It’s more urgent than ever not just to fight the border regime, but to work out how to fight it effectively.

In Chapter 20 we look back over examples of successful resistance, and think about what makes them successful. Actions and campaigns win when they hit the border regime at its limits: from tight budgets and institutional failings, through legal and political constraints, to the ultimate limits of people’s consent.

We note that political action – that is, campaigning to get politicians to change policies – is rarely successful in UK migration struggles. To shift the politics of the border regime we need to shift the wider culture in which millions of people give it their consent. This requires building active movements from the grassroots up: taking effective action, spreading victories, inspiring each other.

But while migrants are on the front line of this struggle, they cannot win it alone. We really start to threaten the border regime when people with and without papers come together in common struggles.