UK Border Regime: immigration raids briefing October 2018

This briefing updates our 2016 report on immigration raids called “Snitches, Stings and Leaks”, and adds new information including a section on resistance and its impacts. It is also a chapter in our new book The UK Border Regime – which is now available to order, or download for free.

For information on what to do if you see a raid, including legal advice cards and posters to print out in many languages, see the Anti Raids Network website.

Raids are the Home Office’s basic terror tactic against migrants inside the UK. Nineteen raid squads across the country – called Immigration Compliance and Enforcement (ICE) teams – hit dozens of addresses each day.

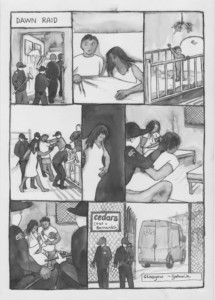

First come dawn raids against residential addresses, to catch people while they’re still sleeping. Later, the squads hit restaurants, shops and factories in “illegal working” raids: there are around 6,000 of these a year, arresting around 5,000 people. Or they join up with police and others in multi-agency operations against public transport, rough sleepers, street markets, and other targets.

Largely based on tip-offs and other “low grade intelligence”, the squads hit easy targets – their great favourite is Indian takeaways. Yet they often come away with few arrests, and many people are released straight away as “not removable”. What the raids do, though, is spread a climate of fear in migrant communities – affecting “legal” as well as “illegal” migrants.

In this briefing first we give a basic snapshot of some main types of raids and who they target. Then we’ll look at a few issues in more depth:

- Informing by “members of the public”. Around 50,000 public tip-offs a year provide the bulk of initial intelligence.

- Employer collaboration. Standard ICE approaches include getting employers to hand over workers’ personal details, including home addresses, or even helping arrange workplace sting operations or “arrests by appointment” – as in the infamous 2016 case of Byron Burgers.

- Entry and interrogation without warrants. Less than half of raids are sanctioned by court warrants. Immigration officers typically claim that businesses give so-called “consent” on the door.

- The impact of resistance. There has been significant resistance to raids in recent years. This has changed the way squads operate, and noticeably dented their arrogance.

Types of raids

The ICE teams carry out various kinds of operations, from crashing wedding ceremonies to linking up with ticket inspectors on buses and at train stations in working class areas. We do not have precise figures, but we know that most raids are of two types: residential raids, and workplace raids.

Until around 2015, high profile “street stops” – stopping and questioning people just walking in the street – were another common tactic. These have decreased in recent years, after provoking controversy as particularly blatant “fishing expeditions” based on racial profiling.

Workplace raids vary from routine corner-shop busts to operations against big factories or multiple premises, possibly involving a number of ICE teams alongside other state agencies. It would be good to do more research on residential raids. But the task is hard: they are highly secretive, happening well away from the public gaze, and with minimal reporting or oversight. And with rare exceptions (e.g. the Glasgow tower blocks that organised against regular dawn raids in the mid 2000s) this means they have faced less coordinated resistance.

There is also a need to investigate raid activities linked to newer hostile environment policies. For example, the “right to rent” introduced in the 2014 Immigration Act requires landlords to check documents of prospective tenants. This may have led to new kinds of residential raids – e.g. ICE teams sourcing “illegal renters’” details from landlords or letting agents.

A snapshot in figures

One statistic the Home Office publishes is the number of arrests made every three months – but only from raids “where the intelligence source type is recorded as information received”. In 2017, 3,034 people were arrested in raids following “information received”. Less than a quarter of them, 697, ended up being deported.i

For workplace raids, a good snapshot comes from a December 2015 report by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI).ii According to this, the Home Office carried out a total of 36,381 illegal working “visits” across the UK in the six years from 2009 to 2014. That is roughly 6,000 workplace raids a year. From those, there were 29,113 arrests, just under 5,000 a year. More than two thirds of visits (24,621, or 68%) didn’t lead to any “illegal workers identified” or arrested, but clearly others ended with multiple arrests. Although we don’t have comparable figures since 2015, we believe the same patterns continue.

The raid squads

There are nineteen ICE teams in the UK. Five of them cover London areas. The Central and North teams are both based at Becket House, next to London Bridge station. The South team is based at the main Home Office headquarters in Lunar House, Croydon. You can see the full list of teams and their bases on the Home Office website.

Each local unit is headed by an Assistant Director. Raid squads on the ground are usually headed by an Inspector or Chief Immigration Officer, and made up of a mix of Immigration Officers (IOs), and Assistant Immigration Officers (AIOs). New officers get just 25 days basic training, plus another three weeks taught by the College of Policing before they are “arrest trained”.

Many recruits come from within the Home Office: junior office workers who take the chance of a more active life with slightly better pay. Others are recruited externally. Quite a few are ex-soldiers, a smaller number are ex-police. On the whole, there is not so much love lost between police and ICE: IOs are paid worse than real cops, and looked down on as ill-trained amateurs.

On the other hand, according to their trade union leader, the ICE team officer who makes the most arrests in a month does get “cake and possibly a box of Roses chocolates”.

Alongside the raid teams themselves, there are much smaller local Operational Intelligence Units (OIUs), staffed by Field Intelligence Officers (FIOs). ICE teams are meant to pass on more serious “organised crime” investigations to the Crime and Financial Investigation (CFI) teams. A separate central unit, called the Civil Penalty Compliance Team (CPCT), is in charge of chasing up penalties for employers found breaking immigration rules.

ICE culture and morale

Some insights into the culture of the ICE teams come from interviews carried out by the Oxford University research project called “Does Immigration Enforcement Matter”.iii The overall impression is of rock bottom morale. Interviewed officers raised many specific complaints, including:

- Confusing internal structures: “the problem is we’ve got so many directorates and strategic, you know, teams, so many little enforcement units around the country” (words of an Immigration Officer); “it’s this obsession with re-branding, even changing the names of units and acronyms” (a Chief Immigration Officer).

- London bias: “a very London-centric organisation” (an IO).

- Stress and overwork: “[we’re told to] keep on nicking people, you just churn, churn, churn” (a former IO).

- Budget cuts and low pay: austerity means smaller teams, intelligence gathering is skipped, staff are moved around the country to deal with crises, and backlogs build up. Above all, officers complained about a ban on overtime: “management said no overtime, seniors said no budget. So what happens, we do unpaid hours” (an IO).

- Outdated IT and an incoherent array of systems. (See The UK Border Regime chapter 11).

- Bullying: “bullying is quite a problem” (a CIO).

- Leading to general low morale: “my incentive to do the job is rock bottom” (an IO), “morale is very, very low” (a former manager).

Who gets raided?

The 2015 ICIBI report gives a snapshot of who is arrested in workplace raids. The number one targets are South Asian men.

Twelve times more men than women were arrested between September 2012 and January 2014. In the same period, 75% of all people arrested in workplace raids were from Bangladesh, Pakistan or India, in that order. The top ten nationalities, in full, were: Bangladesh 27%, Pakistan 27%, India 21%, China 10%, Nigeria 3%, Afghanistan 3%, Sri Lanka 3%, Nepal 2%, Vietnam 2%, Albania 2%.

The gender balance mirrors detention places, but the nationality breakdown is fairly specific to workplace raids. It reflects not just the history of British colonialism, but the types of businesses that offer easy targets. The ICIBI report sampled 184 visit files, and found:

… one hundred and seven of the 184 premises visited were high street restaurants and/or takeaways, mostly Indian Subcontinent or Chinese cuisine, with some fried chicken outlets.iv

The high number of Pakistanis is also connected to the attempt to fill regular charter flight deportations to that country (see The UK Border Regime chapter 8). On the other hand, Chinese people are seen as generally harder to deport – the Chinese government does not co-operate so readily with providing travel documents.

The ICIBI report suggests that Home Office bosses don’t see the obsession with Asian restaurants as ideal: “some ICE managers told us that more attention should be paid to other sectors.” But we still haven’t seen much evidence of change.

In the ICIBI sample, 45% of people arrested were “overstayers”, i.e. people who arrived in the UK on a valid visa but then stayed after it had run out; 20% were “illegal entrants”; 13% were “working in breach” of their visa conditions: e.g. asylum seekers or students working full time.

Timeline: from tip-off to detention

1. Gathering “intelligence”

Intelligence officers sort through tip-offs, add their own leads, and supposedly “research and enrich” them. They then prepare “intelligence packages” on potential targets.

2. Picking targets

Each ICE unit has a weekly “tasking group” meeting to plan operations. This might consider 40 or 50 potential operations, though not all will be approved. It will look at:

- “packages” presented by intelligence officers;

- residential targets sent by case workers and reporting centres, e.g. “absconders” (see The UK Border Regime chapter 5);

- monthly priorities set by national and regional commanders;

- priorities sent by the National Removals Command (NRC), e.g. to fill a charter flight;

- joint working plans with neighbouring ICE teams and with other agencies such as police and local authorities.

In the absence of special instructions, “removability” tops the criteria for deciding targets. Some nationalities are much easier to deport than others: e.g. Albanians and Pakistanis, the biggest charter flight nationalities. At the bottom are Syrians or Palestinians, or nationalities such as Iranians or Russians whose governments don’t readily co-operate in issuing travel documents. The NRC, which is in charge of coordinating all deportations and also authorising detentions, plays a key role here. (See our briefing on deportations.)

3. Planning and legal access

The tasking group will allocate an “officer in charge” for each raid. They should make a plan for the raid and co-ordinate with police or other agencies involved. They may carry out reconnaissance (a “recce”) of the target. However, budget cuts mean nowadays recces are often just a quick look on Google Earth.

In theory, the officer in charge should also prepare a legal means to gain access to the target address. The three main options are: a court warrant; an “Assistant Director’s letter”; or claimed “consent” from the legal occupier of the property. As discussed below, these procedures are systematically abused.

4. The daily grind

ICE teams typically assemble in the early hours (e.g. around 4 to 5 am) for morning briefings, then head out for residential dawn raids. The schedule may change if, e.g. major “joint agency” operations are planned. Raids continue through the day, and into the evening, on workplaces and other targets. Each ICE unit may have two or more teams working simultaneously. They may aim to carry out around five “visits” during the day – although this could also include other duties such as “compliance visits” on employers (see below).

5. The raid

Squads gain entry to the premises, with or without legal “consent”. In theory, they should only question: individuals who have come to their attention through “prior intelligence”; their family members; or other people whose behaviour gives specific grounds to suspect them of “immigration offences”. In practice, though, they just round up anyone who looks or sounds “foreign”. They aggressively question people, and may use mobile fingerprint scanners. They may also search the property, e.g. for documents, money, and driving licenses (in order to prosecute people under the new “driving whilst illegal” law – see The UK Border Regime chapter 10 on Hostile Environment measures).

6. Arrests – “removability”

Arrested people are taken back to the ICE base. This is usually in a building shared with a “reporting centre” (see The UK Border Regime chapter 5) and a cell block called a Short Term Holding Facility. Private Mitie security guards handle custody. But arrests also take one or more immigration officers out of action for several hours to process the prisoners.

That includes calling the National Removals Command, who have to authorise any detentions. This is a source of tension: officers get frustrated if they are instructed to release captives who don’t meet current NRC priorities. Those who are detained will be collected in the evening by a Mitie transport van. Other people may be released with reporting requirements.

7. Aftermath

The proportion of removals following ICE “intelligence led” raids is extremely low. Only 23% of “enforcement visit arrests linked to information received” actually led to anyone being “removed”. Many others will linger in detention for weeks, months, or even years before being let go.

As for the employers, there is the chance of a criminal charge, but the most common outcome is a civil penalty of up to £20,000 per worker (see below). However, the Home Office’s record in actually collecting these fines is poor. According to the 2015 ICIBI report, only “around 31% of debt raised was recovered and […] it took an average of 28.4 months to recover it.”

Allegations: where does “intelligence” come from?

In June 2014, ICE “intelligence” files for a two-week series of nationwide raids called Operation Centurion were leaked to the Anti Raids Network and other campaigners. The files included “intelligence packages” on 225 targets – many of which were then successfully warned. They give a very handy glimpse of how Immigration Enforcement finds its victims. Our 2016 report “Snitches, Stings and Leaks” analysed the files. Here we recap some of the main points.

Debates around immigration raids have sometimes focused on the issue of “racial profiling”. The question hit national media after the Operation Centurion leak, as Labour politician Keith Vaz, then Chair of the House of Commons Home Affairs committee, appeared on TV condemning the way raids appeared to be “fishing expeditions” for particular national groups, rather than being truly “intelligence led”.

And yet there certainly is “intelligence” behind the raids. In theory, all allegations received by Immigration Enforcement are processed onto a central computer system called the Information Management System (IMS).v The Home Office releases some basic statistics on this information. For example, in 2017 IMS had 64,456 information reports. 26,830 were about people with “no permission to stay in the UK”, and 12,538 about “illegal working”. Other tip-offs concerned bogus marriages (6,626), fake or false documents (4,411), lying on applications (3,406), helping other people enter or stay in the country (1,983), smuggling goods (1,718), and human trafficking (985).

Where did the information come from? Another ICIBI inspection report on “The Intelligence Functions of Border Force and Immigration Enforcement”, published in July 2016, helps here. In the twelve months between August 2014 and July 2015, 74,617 allegations were entered into the system. 49,109 came from “the public”, including from calls to the Immigration Enforcement hotline, electronically via a form on the Gov.uk website, and in person to officers. Another 7,540 tip-offs were forwarded from Crimestoppers. 17,818 pieces of information were referred by “other Government departments”. Finally, 150 tip-offs came from MPs – presumably passing on information from constituents.vi

On this basis, it looks like the majority of ICE intelligence consists of snitching from “members of the public”. But how much use does Immigration Enforcement make of these public tip-offs? Many are likely to be “low grade” to say the least. And what proportion of operations come from officers acting on their own initiative, rather than responding to allegations at all?

Public snitching in the Centurion files

The Centurion files give a few hints.vii 30 of the leaked entries offer clues to where the initial lead came from. Eight mention “allegations”. For example, one entry notes an “allegation of 30 illegally working students” at a cleaning company; in an import company an “allegation has been received that they are employing persons illegally”; a manufacturing company is “alleged to be employing [Brazilian] nationals”.

Another seven cases are referrals from other agencies, including three from the police. After a worker contacts the police saying they have been trafficked and forced to work at a meat-packing plant, the police contact IE requesting involvement in a joint operation. In Glasgow, an “Immigration offender [is] encountered by police at Possible House of Multiple Occupancy […] Others possibly residing there.” Elsewhere, police propose a joint op also involving trading standards “during a series of test purchases at off licenses and pubs”. Two cases involve the Security Industry Authority (SIA), which licenses security guards. In one, the SIA passes on a lead on a large security company in Luton; in another, ICE are planning to actually “attend an SIA test and check status of candidates”.

Five cases recycle old targets, including two to firms that haven’t paid old penalties, while another mentions “previous excellent results from enforcement visit”. Two other cases dig up unspecified “old intel”. In two cases, ICE has approached a company to provide information on its cleaning contractors, which then become targets.

If this sample is anything to go by, many ops do seem to start with a tip-off. There is just one mention in the documents of a team “cold calling” to do speculative intelligence gathering, in this case around hotels in South London. Although there is another reference to “markets being scoped/developed”, which might involve teams starting from scratch in a targeted area.

This picture is also supported by the 2015 ICIBI report on Illegal Working. The inspector looked at a sample of 184 cases that had been evaluated according to the National Intelligence Model (NIM) “5x5x5” rating system – a standard model used by the police and other UK law enforcement agencies. In this system a piece of information is classified on three scales: the source is rated from A (always reliable) to E (untested); the particular information is evaluated from 1 (known to be true) to 5 (suspected to be false); and another scale from 1 to 5 indicates who can have access to the information.

In 127 cases, information is said to come from rated “sources”. One fact leaps out: 98 of these are rated as E4: “untested source, information not known personally to source, and cannot be corroborated”. Another eight were rated E3 “untested source, information not known personally to source, but corroborated.” Only 20 were rated as B2 or B3, from “tested” sources, and none as A. In the other 57 cases the source evaluation was “not known, intelligence rating not shown or not clear in file”.

And there is further confirmation from the ICIBI report on “Intelligence Functions” (para 6.11), which adds:

In interviews and focus groups, staff commented that IE was overly reliant on allegations received from members of the public, and did not gather enough intelligence through enforcement teams and Field Intelligence Officers (FIOs). As a result, it was reactive rather than proactive.

In conclusion, there is substantial evidence that Immigration Enforcement “intelligence” does make heavy use of uncorroborated tip-offs from unknown “members of the public”.

However, we should add one last point. Immigration Enforcement has strong political, and indeed legal, reasons to represent itself as “intelligence led”, as not conducting “fishing expeditions”. For this reason, we might expect that available data under-represent operations carried out on the basis of no allegations at all. This would also hold for the Operation Centurion files. If ICE teams are regularly “cold calling” high street takeaways, they are not likely to document this even internally.

So our general conclusion might be: a lot of ICE intelligence comes from uncorroborated public informing; some operations may not be based on any intelligence at all.

Employer collaboration

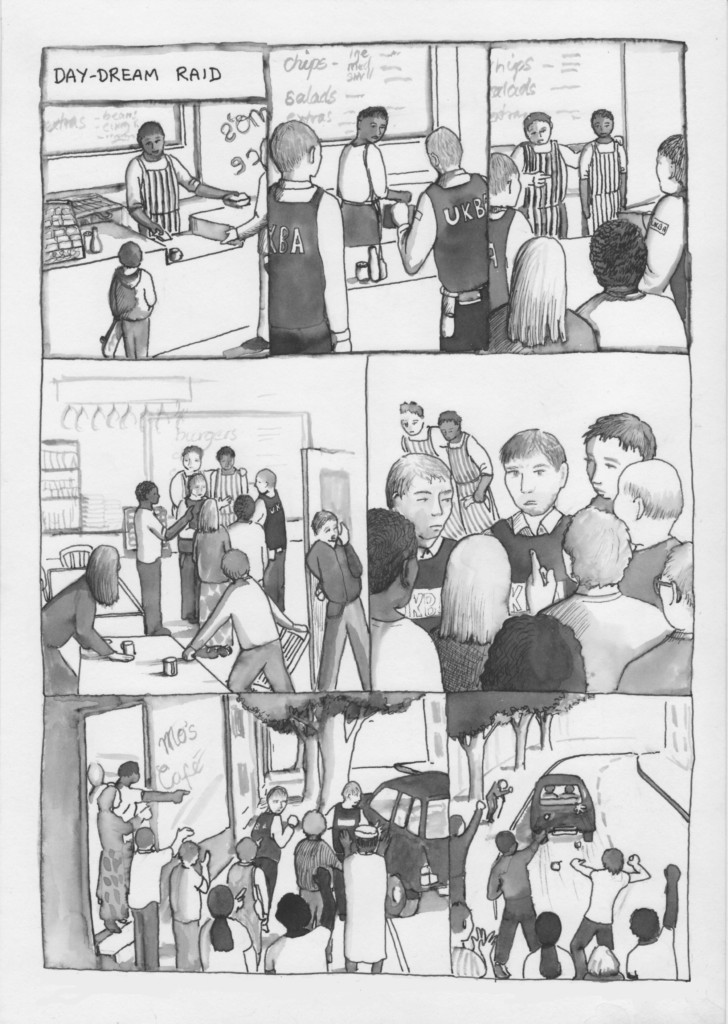

In July 2016 the restaurant chain Byron Hamburgers caused an outcry after setting up a “sting operation” with the Home Office to trap its own workers. Managers called in staff for early morning meetings, described as about “Health & Safety” or “a new kind of hamburger”. When they arrived they were met by ICE officers, who made 35 arrests in different restaurants.

As Byron was hit with pickets, boycott calls and an actual plague of locusts, mainstream and social media debated the morality and legality of its actions. But was the Byron sting an exceptional case, or is this common ICE practice?

Just a few weeks before, on 2 June, ICE had raided the London training centre of Deliveroo, the food delivery courier company, whose workers had been protesting about a cut in wages. The raid was a joint operation with police (focusing on drugs) and the Department of Work and Pensions, and ended with three arrests for immigration offences. Workers present said that Deliveroo management actively assisted the raid and, according to one online report, Immigration Officers arrived with “a list of names with photos of Deliveroo drivers they were looking for”. In a media statement the next day, a Deliveroo spokeswoman confirmed that: “we have worked with the Metropolitan Police to assist in a documentation check at our Angel office yesterday.”

Two earlier high-profile cases occurred in May 2007 and 2009, both involving contract cleaning companies: Amey and ISS. In December 2006, Amey took over the cleaning contract at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Middlessex, and with it a workforce of 36 cleaners. The new contractor moved to “rationalise” staff numbers. The cleaners, who were seeking trade union recognition rights, resisted. Amey’s next move, as told by union rep Julio Mayor, was as follows:

they summoned all the workers to a closed area under the pretext of a training session. 15 minutes after we had assembled, about 60 police and immigration officials arrived and took away six people undocumented in the UK. Part of the policy of Amey was to get rid of the workers who were working there before they won the contract and they used every tool they had. All the workers were Latin American.

In June 2009, ISS, the cleaning contractor for the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, made a very similar move against its largely unionised staff.

Cleaning staff were told to attend an ‘emergency staff meeting’ at 6.30am […] Within minutes the meeting was raided by at least twenty immigration officers. The cleaners were locked in the room and escorted one-by-one into another classroom where they were interrogated.

How common are these kinds of operations? The Amey and ISS cases came to light because some of the workers targeted were active trade unionists and campaigners who raised a public outcry. The case of Byron, too, was initially reported in Spanish speaking media, then raised by Black activist groups on social media, and only picked up by mainstream UK press weeks later after the “#boycottbyron” hashtag went viral on twitter. We can suppose that there are more cases of this kind, which do not receive media attention.

In fact, we can read the following bare statement in the Home Office’s official staff guidance on “Illegal Working Operations”:

The majority of reports about suspected illegal working come from employers.

How does that square with the last section, where we saw that the bulk of information starts with “members of the public”? One possibility is that employers are also counted as “members of the public” in the figures, and so many of the 50,000 tip-offs come straight from bosses. Another is that, even if anonymous tip-offs are often the first lead, ICE teams typically follow up by approaching employers and demanding more information.

Employer collaboration in the Centurion files

This picture is confirmed by the leaked Centurion files. 18 entries explicitly mention discussions between ICE and employers. For example, Midlands ICE teams plan to visit “markets and engage with managers there and do some intelligence gathering there”. In London, “contact to be made with Berkeley Homes over a large construction site in Greenwich”. In another case, “contact made with Holiday Inn […], awaiting return contact from HR”.

In other cases, the entries report that relationships have been established and the company is co-operating. The most common form of cooperation is handing over staff files and other information on workers. E.g.: “Contact made with Coral Bookmakers and William Hill bookmakers for sites across South London, 900+ staff files are being checked and it is conservatively anticipated there will be at least 5 offenders across the sites.” Or in a care home: “staff list of 95 obtained and 8 offenders traced.” One entry mentions the British Horse Racing Association “providing staff details (which we have not yet received)” on stable workers.

Three entries concern recruitment agencies. One case note reads as if the initial approach came from the company: intelligence officers are planning to visit the agency after “they noticed an increase in Africans submitting Italian ID cards and [passports].”

Another interesting entry refers to a visit by Field Intelligence Officers (FIOs) to a recruitment agency where “12 offenders were identified”. It ends: “residential visits to be tasked”. That is, it seems the agency is passing on home addresses of people on its books looking for work, so that ICE can then raid their houses.

As well as passing information on workers, employers may also point the finger at other employers. Two cases are mentioned in the files: in both, Immigration Enforcement is “contacting” or “in communication” with companies – a car auction site and a cinema chain – about their cleaning contractors.

Finally, two entries may indeed refer to Byron-style operations where arrests are set up “by appointment” with bosses. One from the South East team reads: “FIOs are liaising with cleaning companies with a view to arrests by appointment being made.” The other is from the South Central team: “FIO looking at a mid size warehouse […] which is owned by a Chinese national. FIOs are still liaising with cleaning companies with a view to arrests by appointment being made.” Given the very similar wording, these two entries may indeed be talking about the same operation: apparently a large operation against a number of companies, and across at least two local ICE areas.

There is one entry in the documents about an employer, or in fact an employers’ association, not cooperating. Officers contacted the association “to establish information flows however this is looking unlikely due to a reluctance to work with Immigration Enforcement”. This is the only case of non-cooperation noted in the documents. Of course, other potential cases may not have made it into the files for precisely that reason.

The Centurion files suggest that it is very often Immigration Enforcement, acting on a prior tip-off, who initiate contact with employers. This seems to make sense: under most circumstances, why would it be in an employers’ interest to “bring down heat” on themselves? After all, one of the perks of “illegal” labour is that it’s not hard to fire workers.

But we can also think of exceptions. For example, an employer might be unwilling to do their own dirty work of firing workers, perhaps because of social or family connections to workers. Or some employers may be keen to have help in taking on a “difficult” workforce, perhaps where workers are organising. This, of course, is exactly the situation in which Amey, ISS, and possibly Deliveroo, set their stings.

“Educating” employers

In the second half of 2014, the Home Office ran a programme called Operation Skybreaker to pilot a new enforcement approach in the ten areas of highest “known” illegal immigration – all in London. The main change was the introduction of so-called “educational visits” in advance of raids.

Before making an enforcement visit to a business to follow up information received about individuals suspected of working there illegally, IE would first visit the business to encourage them to comply with employment requirements.viii

This scheme has since been rolled out nationwide – although, budget cuts mean teams may not always follow it. “Educational visits” serve a number of objectives. One is public relations, presenting Immigration Enforcement as a friendly service “encouraging” rather than punishing. Another is trying to scare workers into voluntary return, much cheaper than forced deportation. Another is to approach employers about collaboration, whilst gathering more intelligence.ix The Home Office’s evaluation of Operation Skybreaker specifically states that “intelligence generated” from educational visits in the pilot “led to 65 arrests”.x

According to people involved in the Anti Raids Network, this is what typically happens: intelligence officers or ICE teams call into a business, or sometimes telephone. They ask for full staff lists, and may demand further information on specific individuals. The threat, made implicitly or explicitly, is that if firms do not hand over all information requested they will face a hostile raid.

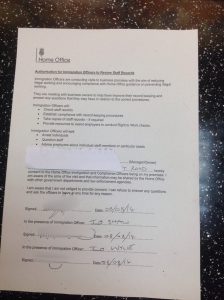

In September 2014, the Anti Raids Network published a copy of a “consent form” Immigration Enforcement had asked a business to sign. This form was headed “Authorisation for Immigration Officers to review Staff Records”. It gives permission to Immigration Enforcement to enter the premises and to check and copy staff records. The gathered “information may be shared by the Home Office with other government departments and law enforcement agencies”.

The form states clearly: “I am aware that I am not obliged to provide consent. I can refuse to answer any questions and ask the officers to leave at any time for any reason”. As this makes clear, ICE are well aware that companies are not legally obliged to hand over personal information on workers. But they don’t make a habit of explaining this to scared shopkeepers.

Anti Raids Network write:

“During our outreach, we have found that a lot of people have been signing consent forms. However, when we’ve told people that there is no obligation to sign, many said that they were unaware that it was voluntary, while others said ‘you can’t do anything to stop them – they do whatever they want’. In practice of course, it is very hard to refuse – regardless of whether this is your legal right.”

Pressuring collaboration

This brings up an important legal question. In the Byron Hamburgers case, the chain’s media defenders argued it was legally obliged to co-operate with Immigration Enforcement in setting a trap for its workers. This is not true. The choice was not legal but financial. Here are the basic points:xi

- The 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts – part of Theresa May’s hostile environment drive – make it a criminal offence to employ someone if the employer “knows or has reasonable cause to believe that the person has no right to do the work in question”.xii For example, an employer could be convicted if the court finds they “deliberately ignored information or circumstances” about the worker’s status.

- In addition, an employer is also liable to pay a civil penalty for employing someone who doesn’t have the legal right to do the work. This is separate from the criminal matter: ICE can impose a civil penalty simply by issuing a notice, without having to go before a court and prove their case.xiii

- But the employer does not have to pay if they can show evidence that they have “correctly carried out the prescribed right to work checks using acceptable documents”. (Legally, this is a “statutory excuse”.) This involves checking the worker’s ID documents, and not accepting these documents if it is “reasonably apparent” that they are false or do not belong to the worker.xiv This would apply if the documents are obvious fakes – but not, for example, if they are clever forgeries the company couldn’t be expected to spot.xv

- If the employer fails to show it has done the checks correctly, it faces a maximum penalty of £20,000 – or £15,000 if it has not been found employing an illegal worker during the last three years.

- But the penalty can be reduced on certain grounds. Crucially, these include: £5,000 off for reporting suspected illegal workers to Immigration Enforcement; another £5,000 off for “actively co-operating”, which involves granting ICE access to premises and answering all questions and document requests.xvi

To sum up: there is no general legal requirement for companies to hand over any documents in advance of a raid. Companies may choose to show documents to prove they have correctly applied right to work checks.

On the other hand, while there is no legal obligation, there are financial incentives – if the company thinks it may get caught hiring “illegal” workers, it can reduce penalties by “co-operating”. For example, in the Byron Burgers case, the company had already been caught in 2015, so less than three years before, employing at least one illegal worker. But it could have got its penalties halved to £10,000 rather than £20,000 by reporting its workers and then “actively co-operating”.

Two tier economy

Immigration Enforcement does not stop people working illegally – but it makes people work fearfully. It helps maintain a segregated “two tier workforce” in which hundreds of thousands of workers have no access to the rights or safeguards available to others. Fear of raids keeps workers in the lower tier scattered, unseen and unheard. The threat of Immigration Enforcement provides the ultimate human resources tool to stop workers becoming “difficult” and organising to demand improved rights or conditions – as seen in the cases of Amey or ISS.

It is important to see that this is not an issue just of a peripheral minority. Illegal workers are at the heart of the UK economy: building workers, office cleaners, food pickers and packers, warehouse lifters, drivers and couriers, the menials in every service industry. The “discount” on illegal workers makes a fundamental contribution to every business model.

But while every blue chip company relies on “illegal” labour this is not illegal – for them – so long as these workers are not directly employed. Only the base level contractors or sub-contractors who immediately hire cleaners or labourers are liable for “right to work checks” and penalties.xvii As we saw, one Immigration Enforcement tactic is to approach higher tier companies for information on contractors. Raids are usually kept at base level, leaving the “respectable” companies unscathed.

Fabricating consent

In many vampire stories, the undead can enter a building only when invited in by the occupiers. ICE teams often work on a similar principle.

There are currently four main ways they can legally gain access to a property. These are:

- Warrant granted by a magistrate’s court

- Assistant Director’s (AD) letter

A Home Office Assistant Director has a special power to authorise entry without a warrant. This is only meant to be used in urgent situations where it would be unreasonable to wait for a warrant.

- “Informed consent”

The legal occupier of the property can grant officers their consent to enter. According to Immigration Enforcement guidance, this means “a person’s agreement to allow something to happen after the person has been informed of all the risks involved and the alternatives”.xviii The ICIBI Illegal Working report clarifies that “the guidance requires ‘fully informed’ consent in writing by a person ‘entitled to grant entry’”.

- Licensed premises exemption

The Immigration Act 2016 gave ICE teams a new power, which came into force in April 2017. They are now legally able to enter businesses if these are “licensed to sell alcohol or late night refreshment”. It does not apply to other kinds of “licensed premises” such as entertainment venues or members’ clubs.xix This will do nothing to halt ICE’s habit of raiding curry houses.

In the 2016 ICIBI report on Illegal Working Operations (so before the new licensing power), the Inspector looked at how raids were carried out for the sample of 184 cases. This included how ICE teams gained entry to targeted premises. In 79 cases, the teams had court warrants. In three cases, the power of entry was not clear in the records. In the large majority, 102 visits, Immigration Officers entered without any warrant – claiming they had informed consent to do so.

An earlier ICIBI inspection from 2014 found widespread abuse of the AD Letter power: letters were used routinely, rather than only in exceptional cases.xx Following that report, the use of letters seems to have gone right down.

As we noted, “informed consent” is meant to be in writing, and only “after the person has been informed of all the risks involved and the alternatives”. According to people involved in the Anti Raids Network, this is what really happens: ICE officers turn up at the door and ask to speak to the manager, while other officers may already have sealed off other exits to prevent people from leaving the building; the officers then ask the manager (or an available worker) for verbal consent to enter the premises, or at best to sign a paper granting written consent on the spot.

As the ICIBI report notes, there is minimal recording of how consent was established. The inspector saw no records of how squads checked the person they spoke to was “entitled to grant entry”. And, “in most premises visited, English was not always the first language of those encountered.” “Files rarely documented how officers confirmed that consent was ‘fully informed’ as required.”xxi There is no requirement for teams to keep signed consent letters on file and available for inspection. So there is no way for consent to later be proved or disproved, or for the officers involved in gaining consent to be held to account.

Questioning

Consent to enter is one issue; another is consent for questioning. The law and Home Office guidance allows Immigration Enforcement to enter premises in pursuit of specific named individuals suspected of immigration offences – again, this is key to the claim of “intelligence led” operations. Officers do not have a general power to question anyone else. They may only “invite” other people to answer “consensual questions” if “they had brought themselves to attention, such as by ‘behaviour (for example an attempt to conceal himself or leave hurriedly)’.”xxii

Once again, the ICIBI Illegal Working report shows that Immigration Officers routinely break the rules:

In the 184 files we sampled there was no record of anyone being ‘invited’ to answer ‘consensual questions’. The files showed that officers typically gathered everyone on the premises together, regardless of the information known or people’s actions.xxiii

Even if raids are initially targeted based on some form of (low grade) “intelligence”, once inside the building they become a general round-up.

Resistance and its impact

There has always been resistance to immigration raids. But in the last five years or so it has become substantially more visible, and this has had significant impacts on ICE tactics.

Here are just a few examples of recent resistance:

- February 2013: demonstration and anti-raids patrol of Old Kent Road, South London, which disrupts raid.

- August 2013: Southall Black Sisters chase raid squad out of Southall, London.

- June 2014: leak of “Operation Centurion” documents, after which nearly 200 targets across the UK are warned.

- May 2015: a large crowd chases raid out of Peckham, South London, video “goes viral”.

- June 2015: over 100 people try to rescue arrested man on East Street, South London.

- July 2015: locals chase major immigration raid out of Shadwell, East London, and sabotage vans – the Daily Mail spreads the story blaming a “Muslim gang”.

- 2016-17: after a wave of raids targeting the fast gentrifying Deptford Market in South London, raids are chased off and vans smashed, local traders organise a network to alert each other and resist raids together.

These are just a few high profile stories that have spread, whether through national media, social media, or at street level through leaflets, posters, and word of mouth. There are many more smaller scale examples.

An initiative called the Anti Raids Network was formed in 2012 to spread information about raids and how to resist them. As its members point out, this is by no means responsible for “organising” the widespread local resistance against raids. It helps circulate raid alerts, and stories of resistance. Local groups involved with the network have also run legal and practical workshops, held local information stalls, and more.

There was a noticeable shift in Immigration Enforcement approaches after the major episodes of Summer 2015. ICE teams were clearly nervous about growing resistance. Stories of “mobs” and smashed windscreens spread from London, and were talked about by anxious officers in Wales and Scotland. Numerous incidents were reported where raid teams now backed down and left after just a few people “stood up” to them. That could mean as little as simply blocking entrances, handing out “know your rights” cards, or just shouting at squads to go away. ICE teams also monitor social media to see if there are call-outs for people to gather and resist raids.

Our understanding is that, after resistance began to spread, ICE orders were as follows:

- If squads anticipate resistance when planning a raid, e.g. in areas known to be “troublesome”, they should ask for police to accompany them.

- If during an operation squads think people are gathering to resist them, they should hold off and call a senior commander back at base.

- Very often, the commander will instruct them to quit the operation (make a “tactical retreat”). Back-up is limited, and senior officers do not want to take responsibility for giving the order if something goes wrong.

On the other hand, we have also heard of more recent cases (since 2017) where ICE commanders have instructed officers to arrest people (including UK citizens) for “obstruction”. This may often backfire. Immigration Officers are not trained in “public order” tactics or law, and in the cases we have heard of, people arrested were later acquitted or charges were dropped as ICE bungled their procedures.

In 2017, we know of at least two people arrested for “obstructing immigration officers” – in both cases, the cases collapsed before or in court. Earlier, the “East Street Three” were people singled out from the resistance on 21 June 2015 and charged with “violent disorder”. Two were acquitted by a jury, charges against the third were later dropped. In 2016, ICE teamed up with a Metropolitan Police “gangs unit” for a “sting operation” where a fake raid was staged off Deptford High Street. Two people were arrested for alleged criminal damage – but again, both were acquitted. Of course, there may well be other people we don’t know of who have suffered repression for resisting raids.

It is important to remember that ICE have neither the powers nor the training of police officers. They are not used to serious resistance, the mainstay of their job is kicking down sleeping peoples’ doors. They rely on police support for more difficult operations – but police commanders rarely see helping ICE as a priority. In addition, as discussed above, immigration raids may often themselves be unlawful due to the routine abuse of warrants or “consent”, so squads may not want to draw attention to their own rule-breaking.

In the last year or two, resistance has been somewhat quieter in London. But, as we write, new local Antiraids groups are forming and holding street stalls in London areas (in Newham and Waltham Forest). In Bristol on 25 October, 100 people blocked a street for five hours to hold off a raid van.

Raid resistance is a very accessible and powerful form of action against the border regime. Raids happen right by us, in our workplaces, on the streets we walk down every day. No special expertise or equipment is needed to take action. And action is very often successful. Stopping a raid has a very direct impact, someone isn’t detained. But also, the experience of standing up to the border regime and winning empowers those involved, and inspires more people to stand up too.

iNB: the deportations figure comes from Home Office data released the quarter after the arrests figure. Thus it only records people deported in the 3-6 months after they were arrested. Some more people may be deported later, after being held for a longer period in detention.

iiICIBI report on Illegal Working operations, December 2015. Hereafter, we will refer to this as “ICIBI Illegal Working” report. http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ICIBI-Report-on-illegal-working-17.12.2015.pdf

iiiThe quotes here come from a presentation given at the COMPAS “Does Immigration Enforcement Matter?” conference held in London on 27 October 2017.

ivFor example, raids targeting rough sleepers have been focused on East Europeans. Residential raids are likely to hit all nationalities deemed “removable”. A Freedom Of Information request to which the Home Office replied in 2013 (after appeal) also confirms that “restaurants and takeaways” are primary targets. In 2011 there were 2,591 visits to these businesses, leading to 1,939 arrests; in 2012 there were 2,514 visits, with 2,320 arrests. Comparing these figures with the ICIBI Illegal Working report, in both years 47% of all raids were to “restaurants and takeaways”. Home Office reply to FOI request submitted by Nadeem Badsha, January 2013. https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/immigration_raids#incoming-351316

vThe Intelligence Management System (IMS) is the main information recording system for Immigration Enforcement, also used by Border Force. See ICIBI: Inspection report on the intelligence management system, October 2014

IE intelligence officers also have access to various other internal or cross-agency computer systems and are supposed to use these to cross-check intelligence on targets. These include the following: CID; CRS (Case Reference System – a HO database containing details of all visa applications); Experian – commercial database holding credit reference information and personal information held by financial institutions; Warnings Index – a HO System used to ascertain whether individuals are of interest to the Home Office; Home Office National Operations Database; Police National Computer. See ICIBI intelligence report 2016.

viICIBI intelligence report 2016

viiThe Operation Centurion files have not been published themselves because they contain personal information naming businesses and sometimes individuals. Here we quote from the files and anonymise where necessary.

viiiICIBI Illegal Working report para 4.13

ixAnti Raids Network analysis of Operation Skybreaker: https://network23.org/antiraids/2014/09/25/operation-skybreaker/

xICIBI Illegal Working report para 4.16

xiThis legal argument was made in more detail in Corporate Watch’s 2016 report “Snitches, Stings and Leaks”. Migrants’ Rights Network then commissioned Dr. Katie Bales, a lecturer in law at Bristol University, to give a professional opinion on the legal obligations of employers, which backs up our conclusions. We should also note that much of the relevant immigration law has never been tested in court – in part because those targeted in raids often disappear into detention or may indeed be deported. See Katie Bales: “Employment and immigration enforcement: The legal limits of what can be required from employers”, Migrants’ Rights Network, September 2016. https://migrantsrights.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Katie-Bales-on-HO-raids-in-businesses.pdf

xiiThe 2016 Immigration Act added “has reasonable cause to believe”, which came into force on 12 July 2016. Prior to that, under the 2006 Act, the prosecution had to prove that the employer knew that the employee was working illegally. See the new issue of the government “Employer’s Guide to Right to Work Checks”: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/536953/An_Employer_s_guide_to_right_to_work_checks_-_July_16.pdf

xiiiMore precisely, the procedure is this: Immigration Enforcement (e.g. an ICE team) issues a “referral notice” to the employer stating that they have found illegal workers and that the case will now be handed to the “Civil Penalty Compliance Team” (CPCT); the employer has a chance to object; if the employer does not object or the objection is unsuccessful, they are issued with a second “Notice of Liability” that demands a payment; the employer can also appeal to a civil court to dispute the penalty. See “Code of Practice on Preventing Illegal Working”. See page 10 of that document for details of what it means to correctly carry out right to work checks. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/311668/Code_of_practice_on_preventing_illegal_working.pdf

xivMore technically: having a statutory excuse is one of three grounds of objection or appeal to the civil penalty. The others are that the employer is not in fact liable (e.g. they weren’t really the illegal worker’s employer), or that the penalty is too high. See “Code of Practice on Preventing Illegal Working” https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/311668/Code_of_practice_on_preventing_illegal_working.pdf

NB: there is a Home Office “statutory excuse checksheet” which states clearly what evidence Immigration Officers should look for when judging whether employers made the checks correctly. Basically this amounts to two things: a clear copy of the relevant pages of the worker’s passport or other acceptable ID document; and a record of the date when it was checked (for example, by dating the ID document copies). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/313369/Statutory_Excuse_Checksheet.pdf

xvFor example, the Independent Chief Inspector specifically discusses a case where the CPCT penalty team: “considered that the identity documents provided by many of those arrested were fraudulent, but determined that this was not ‘readily apparent’ so cancelled all but one civil penalty.” (ICIBI Illegal Working report, figure 18)

As the Inspector puts it,“employers are either negligent in respect of their obligations to check their employees’ ‘right to work’ or complicit in hiding such work from the authorities.” (ICIBI lllegal Working report, forward)

xviFull details are in the Home Office: “Code of practice on preventing illegal working: code of practice for employers” (May 2014) https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/311668/Code_of_practice_on_preventing_illegal_working.pdf

xviiGovernment FAQ for employers on illegal working and civil penalties, Answer 44: “If the employer is contracting out specific jobs or services for individuals (contractors and sub-contractors), there is no need for a right to work check when they are not being employed by the employer.” https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/426972/frequently_asked_Qs_illegal_working_civil__penalty_May_final.pdf

xviii ICIBI Illegal Working report, para 5.18

xixAlthough this power is framed in terms of licensing law, it doesn’t only apply to joint operations with licensing officers. ICE can also enter licensed premises all on their own, “to investigate illegal working following receipt of intelligence on premises they have reason to believe are being used for a licensable activity”.

Home Office: “Guidance to licensing authorities to prevent illegal working in licensed premises in England and Wales”, 6 April 2017 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-powers-to-tackle-illegal-working-in-licensed-premises

Home Office summary statement on the new power from its website: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-powers-to-tackle-illegal-working-in-licensed-premises

The actual law is here (see Part 4 on “rights of entry”):

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/19/schedule/4/enacted

xxICIBI, “An inspection of the use of the power to enter business premises without a search warrant”, March 2014 http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/AD-letters-report-Final-Version-for-Web.pdf

xxiICIBI Illegal Working report, para 5.22

xxiiICIBI Illegal Working report, para 5.27 Another legal justification for questioning someone could be that their immigration status is perceived as dependent on that of someone initially under suspicion, e,g., a spouse or other family member.

xxiii ICIBI Illegal Working report, para 5.28