What to make of COP21?

[responsivevoice_button]

A couple of grassroots activists who are members of the Corporate Watch co-op travelled to Paris for the counter-mobilisation to the UN COP21 climate summit. Here are some of their reflections on the agreement, the mobilisation and the ‘climate movement’ (originally published on Open Democracy 14/01/16)

The Agreement

We won’t spend too much time discussing the agreement itself as plenty of others have done that already (see this excellent summary from ROAR magazine https://roarmag.org/essays/three-reasons-paris-climate-deal-fraud/ and this from climate scientist, Kevin Anderson http://kevinanderson.info/blog/category/quick-comment/). But suffice to say: the agreement is, to a large extent, a pile of crap.

Firstly, the only binding parts of the agreement are for countries to make vague commitments for their emissions reductions and revisit them every five years. Bizarrely the commitments themselves are non-binding, so there is no legal requirement to stick to them. Even if countries do stick to their so-called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) we will be headed for a disastrous 2.7 – 3.7 degrees of warming. As things stand it seems extremely unlikely that they will fulfil their INDCs, considering the now defunct Kyoto protocol, which was legally binding, was ditched or ignored by those who ratified it as soon it became inconvenient. All this shows the emptiness of the stated aim in the agreement to keep temperatures “well below two degrees”, and assurances “to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C” seem ludicrous.

In addition, the agreement does not cover aviation or shipping, both huge emissions sources, and fails to mention oil, coal, gas or fossil fuels anywhere in the text. These omissions would be astonishing in an international agreement on climate, were it not for the obvious and still powerfully pervasive influences of industry lobbying and corporate power.

The agreement also provides absolutely no realistic (or even unrealistic) route to achieving the necessary reductions in greenhouse gas concentrations. It does however rely heavily on green capitalist approaches, technofixes and ‘negative emissions technologies’ such as Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), among other magical ‘solutions’. CCS is a good example of supposed technological solution that, despite its severe limitations and perhaps even non-viability, is continually fallen back upon as a way of reducing greenhouse gas concentrations. It is popular with industry and governments because it deflects attention away from actually reducing emissions at source, or more importantly, challenging the capitalist logic behind our ever increasing consumption of resources (see Corporate Watch’s technofixes report here: https://corporatewatch.org/publications/2008/techno-fixes-critical-guide-climate-change-technologies and our climate capture and storage factsheet here: https://corporatewatch.org/resources/2014/carbon-capture-and-storage-factsheet ).

More radical positions lobbying the negotiations were bought off by including various terms in the ‘preamble’ (which is outside of the agreement and so next to meaningless) or other parts of the text. Some say that the reference to “climate justice”, “just transition” and “indigenous rights”’ in the preamble or the agreement to “pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C” will allow social movements to hold those in power to account. This seems optimistic at best, and it does nothing to address the nature of the power that governments hold and still relies on ‘our leaders’ making the right decisions on our behalf.

Unfortunately many of the civil society organisations involved in the talks are celebrating, using the logic that any agreement is better than none at all. Only a few of the more radical NGOs have denounced it for the farce that it clearly is. In reality it will be impossible to meet even the modest targets of the agreement within a capitalist context of ever expanding economies and ever greater use of resources.

Climate Justice

The term climate justice has been commonly used during climate mobilisations and Paris was no exception, appearing on banners, and in press releases and speeches throughout the summit. However, its use was not restricted to those committed to any meaningful understanding of justice.

‘Climate justice’ has always had varying interpretations, but in the past they were mostly based on politicising the debate around climate change and shifting it towards its root causes, as well as historic and current injustices. However, the term is increasingly being adopted by politically dubious individuals such as the ex-president of Ireland, Mary Robinson (http://www.mrfcj.org/) and even Narendra Modi, the neoliberal, Hindu nationalist prime minister of India. After the Paris agreement was signed, Modi tweeted:

“Outcome of #ParisAgreement has no winners or losers. Climate justice has won & we are all working towards a greener future. @COP21 @COP21en”

He may have been deliberately misusing the term (which was certainly never understood to mean there would be “no winners or losers” from the negotiations), but, along with its inclusion in the agreement preamble, such usage is a clear sign of the extent to which the term is becoming co-opted.

There is a similar situation with the phrase ‘system change’. ‘System change not climate change’ was once a popular slogan with the more radical groups mobilising around climate negotiations, referring to the need to change the economic and political systems causing climate change. Now, due to its use by various reformist organisations, the term seems to have lost its teeth entirely, and is now used to refer to anything from reigning in the worst excesses of neoliberalism, or even just policy reforms.

The co-option and contestation of terms used in mobilising resistance is a common occurrence, and no doubt some will continue to attempt to revert such language to its original intended meaning. However, the vagueness of terms such as ‘climate justice’, ‘just transition’ and ‘system change’ lend themselves to being co-opted. A more explicit analysis of capitalism and the other oppressive and exploitative systems and ideologies behind climate change would perhaps be more powerful and not so easily undermined.

Ultimately of course all these terms and slogans are just words. It is the organisation and orientation of struggles and the forms of action they take that will be relevant in achieving any significant steps in tackling climate change.

The Mobilisation

Many would argue that the days of effective summit mobilisations are long gone, that things have moved on and the securitisation imposed by the state under the guise of the war on terror means that it is no longer a viable tactic. It’s true that previous movements against WTO and trade summits took on something of a summit-hopping character, and that the state became more and more effective at crushing them. But mobilisations can act as rare opportunities for people to come together, not only to learn from one another but also as an experienced realisation of being part of something bigger. The point is that any mobilisation should not not seen as an end in itself, it should spread long before and after and act as way of supporting other forms of grassroots organising not detracting from them.

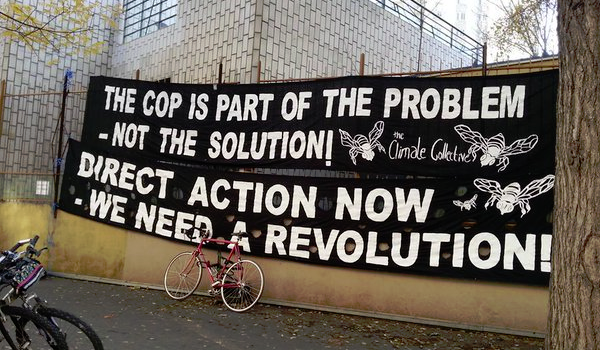

COP21 began with a march and a small but determined riot after French cops enforced the draconian ‘state of emergency’ ban on demonstrations and attacked a protest at Place de la République on 29 November with batons, tear gas and pepper spray. People fought back (see here). The NGO 350 Degrees, who were part of the anti-COP21 coalition, shamefully joined the French president and the mainstream media in denouncing the demonstrators for defending themselves. Others, such as Naomi Klein, while falling short of outright condemnation, certainly distanced themselves from more militant actions (see herehttp://theleap.thischangeseverything.org/shock-resistance-in-paris/ ).

The D12 (December 12) mobilisation was ambitiously billed as the ”largest climate civil disobedience” ever. In the event, it was a long way from being the largest, and it is debatable whether it can really be deemed ‘civil disobedience’ at all. On D12 around 15,000 people held a rally on one of the avenues leading to the Arc de Triomphe and then marched to the Eiffel Tower. The day had a carnival atmosphere, sitting uncomfortably with the self-congratulatory speeches of Hollande and Obama, which were being made as the march was going on. As the pictures of the march were broadcast live, those watching could have been forgiven for thinking demonstrators were celebrating the agreement.

The D12 (December 12) mobilisation was ambitiously billed as the ”largest climate civil disobedience” ever. In the event, it was a long way from being the largest, and it is debatable whether it can really be deemed ‘civil disobedience’ at all. On D12 around 15,000 people held a rally on one of the avenues leading to the Arc de Triomphe and then marched to the Eiffel Tower. The day had a carnival atmosphere, sitting uncomfortably with the self-congratulatory speeches of Hollande and Obama, which were being made as the march was going on. As the pictures of the march were broadcast live, those watching could have been forgiven for thinking demonstrators were celebrating the agreement.

D12 was organised on the basis of an “action consensus” (http://coalitionclimat21.org/en/d12-action-consensus) that committed participants to “only use non-violent and pacifist methods and tactics to show our determination, but won’t contribute to escalation.” At various action briefings and trainings in Paris, participants were told that “breaking police lines” and “property damage” were against this consensus, amounting to a ban on D12 participants defending themselves from the police. This consensus was adhered to by some of the less reformist groups, including Reclaim the Power from the UK.

The French police force have a long and ignoble history of violence. Last year, police killed eco-activist Remi Fraisse at the ‘Zone a Defendre’ in Testet in South-West France (see here http://rabble.org.uk/no-justice-no-peace-for-remi-fraisse-killed-by-the-french-state/). Remi was only one of the countless people who have been killed or brutalised by French cops over the years. French social movements have responded by defending themselves against police violence, often rioting on the streets of French cities in response to police murders. To ask people to accept a consensus that would leave D12 participants defenceless against police violence discounted this culture of resistance and self defence. It is likely to have alienated people from the very social movements in Europe that the anti COP21 mobilisation should have been reaching out to.

Even the more dogmatic adherents to non-violence usually accept that damage to property is not ‘violence’. Why then was damage to property deemed against the “action consensus”? If we are to truly deal with the causes of climate change and challenge capitalism, then the capitalist infrastructure which is destroying the planet will have to be put out of action.

Members of the D12 coalition were involved in protracted negotiations with the police over whether demonstrations could take place and where they would be. Can D12 really be called an act of ‘civil disobedience’ when the majority of demonstrations were approved and sanctioned by the state?

Most of the participants in D12 had not been consulted and had no say over the ‘action consensus’ or the negotiation with the police. They were agreed ahead of time by the coalition, which included NGOs like 350. The involvement of these NGOs, and the decision of social movements to join their coalition rather than organising autonomously appears to have been the main reason that D12 and the Paris mobilisation more generally did not choose to take radical action. The big NGOs who took part in the D12 coalition have a vested interest in ensuring that the demonstrations they are involved in remain law-abiding, and are not too troublesome for the state. They are official organisations that have a lot to lose if they take a confrontational stance. As such, they are not in a position to take the risks necessary to challenge capitalism or the state, and it makes more sense for grassroots social movements to organise independently of them.

Similarly, from what we could see, the talks and events organised by the counter mobilisation had precious few voices from grassroots ecological and anti-capitalist movements in Europe. There were talks and workshops with voices from the Global South, often organised in partnership with the big NGOs, but there were fewer opportunities to hear from, for example, the French ZAD movement (http://zad.nadir.org/?lang=en), the Italian No TAV movement (see www.presidioeurope.net and www.notav.info) or the UK anti-fracking movement (for example Frack Offhttp://frack-off.org.uk/). The inevitable biases in who the NGOs chose to represent the Global South is a serious problem, but not one that we have space to go into here.

The lack of participation of more radical movements from Europe is partly because the mainstream parts of the climate coalition are hesitant to promote those who use real civil disobedience in Europe. Perhaps more importantly, many of those involved in these movements saw the anti-COP21 mobilisation as irrelevant and stayed away. The result was that the NGOs’ messages came through loud and clear, while those of the more radical European grassroots movements were drowned out, or not present at all.

Positives

Despite the inevitable sham agreement and some major issues around the mobilisation and the nature of the ‘climate movement’, there were some positives.

Firstly there was a bit less of the ‘last chance to save the world’ approach seen at COP15 in Copenhagen. Although the radical grassroots mobilisation around Copenhagen always expected the negotiations to fail, the desperate all-or-nothing ‘Hopenhagen’ approach of the mainstream NGOs, followed by many of them subsequently dropping climate as an issue, certainly had an impact on the wider climate ‘movement’. There were other, perhaps more significant factors that are sometimes ignored. One example is the effects of the economic crisis, as austerity began to dominate politics environmental issues received much less attention. But whatever the causes, there was certainly a big dip in movement activity following the summit in 2009.

Things seem different this time, with many in the climate movement focusing on what is to come after after Paris, even some from the more reformist end of the spectrum. The Paris summit had the added benefit of occurring at a moment when the climate movement was already on an ‘up-swing’ and seems to be gaining momentum.

There was also a slightly more politicised framing of climate change in the overall messaging of the mainstream NGOs. Having said that, another positive for us was actually the increasing separation between NGOs and climate-related social movements, with NGOs being increasingly called out for their proximity to the negotiations and acquiescence to government and corporate positions. Some may say that this is a sign of a fractured movement, but we see it as a positive development, where increasingly political differences around the root causes of climate change are leading (rightly) to a waning of NGO control of the climate discourse and a steady deepening of the radical social movements’ analysis of climate change. That said, there still seems to be a degree of hesitation even among the more radical groups in identifying capitalism as a central systemic cause.

Where next?

So where next after Paris? Examples of resistance to fossil fuels, resource extraction and environmentally destructive projects around the world are growing in strength and number. The opposition to tar sands, fracking, open cast coal, mountain top removal, mega-dams, airport expansion and many others are providing powerful sites of struggle and will surely be vital parts of any successful movement to mitigate global climate change.

In Europe, to give just a few examples: No Tav and ZADs mentioned above, Ende Gelände (https://ende-gelände.org/) in Germany, Skouries Gold mine in Greece, are all thriving radical campaigns of resistance uniting locals, environmental activists and anarchists.

There is also a coalition (which perhaps unfortunately includes 350) mobilising for people to take action against fossil fuel projects around the world in May 2016 (see www.breakfree2016.org/ )

However, there is also a need for more connection between ecological movements and struggles against capitalism and social control. We wrote a short text before the summit discussing some of these dynamics (see here: https://corporatewatch.org/news/2015/dec/07/capitalism-or-world), and we include this section to summarise our thoughts:

‘As the world warms, and impacts on scarce vital resources increase, we can expect to see a rise in militarism, securitisation, and repression. But there will also be a rise in disobedience, defiance and resistance. In these turbulent times, possibilities will arise and openings will appear. We need to be bold, and when the time comes, using diversity of tactics and strategies, take action and attack capitalism and oppression in all its myriad forms, all the while imagining and creating alternative ways of living.

‘As the world warms, and impacts on scarce vital resources increase, we can expect to see a rise in militarism, securitisation, and repression. But there will also be a rise in disobedience, defiance and resistance. In these turbulent times, possibilities will arise and openings will appear. We need to be bold, and when the time comes, using diversity of tactics and strategies, take action and attack capitalism and oppression in all its myriad forms, all the while imagining and creating alternative ways of living.

While our struggles are shared, they are not homogeneous, and each is relevant to their individual contexts. But they also need to be interconnected, so we can communicate, learn and develop mutual understanding. If ecological threads can be woven through the many existing struggles around the world we can continue to dissolve the false separation between the social and ecological. Building on the rich history of many generations fighting oppression, this is not the beginning but a continuation. Across the globe struggles are growing, spreading and adapting. If we are to succeed we need all these currents to flow alongside each other, each following their own path, mixing and building until collectively they become unstoppable.

“We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable – but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings..”

Ursula K. Le Guin’