Who is immigration policy for? (Full report)

Download this report as a PDF document.

What really drives the “Hostile Environment”?

For 20 years UK governments have continually introduced new immigration control measures, each more vicious than the last. The Conservatives’ current Hostile Environment approach (see our detailed report on how it works) builds on Blair’s legacy. Labour passed five major immigration acts in 1999-2009, dramatically expanding the detention and deportation system and making swingeing attacks on asylum rights.

The official aim of all these policies is “control”: whether that means simply cutting numbers, or making sure only the “right” kinds of immigrants enter. But, in those terms, none of these clampdowns actually work. Migration figures continue to rise, while the ineffectiveness of vicious Immigration Enforcement measures is an open secret amongst Home Office officials. The level of resources – and violence – required to really seal borders would go well beyond anything yet seen.

This report examines the following key points:

- Immigration policy isn’t really about controlling migration, it’s about making a show of control. It is a spectacle, an emotional performance. In practice, this means attacking a few scapegoats seen as “low value” by business – often, the very weakest migrants, such as refugees, so-called “illegals”, or others without the right documents.

- The primary audiences for the spectacle of immigration control are specific “target publics”: some older white people who are key voters and media consumers, and who have high anxiety about migration – but who only make up around 20% of the population.

- Policies are drawn up by politicians and advisors in close interaction with big media. Political and media elites share a dense “ecology of ideas”, and anti-migrant clampdowns are part of their internal jostling for power – votes, promotions, audience share.

- Migration scares and clampdowns are part of a broader pattern – the anxiety engine that drives much of politics today, fuelled by stories of threat and control.

Some implications

How can we counter the anti-migrant propaganda machine? This analysis calls into question some approaches currently popular in pro-migrant campaigning. Campaigners often aim to get alternative views and voices into the liberal media sphere, trying to influence the “public debate” on migration. But there is no “public debate on immigration”: this idea is a charade that obscures how power really works. There is no one public, but many different people often having quite separate conversations. And it’s not a debate, it’s a propaganda war, fought not with facts and reasons but with emotive stories. As Conservative campaign guru Lynton Crosby says: “when reason and emotion collide, emotion invariably wins”.

Right-wing politicians and propagandists, at least the clever ones, are well aware of these points. They understand who they need to talk to, and how they need to talk to them. This isn’t to say we should copy their strategies, as indeed our aims and values are very different. But to strategise effectively, first we need to understand how the enemy works.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: what is immigration policy for?

2. From Public Opinion to Target Publics

3. Politicians: immigration and elections

4. Politicians: Home Office agendas

5. Media and politicians: a dense ecosystem

6. Media and people: communication power

11. Conclusion: thoughts for resistance

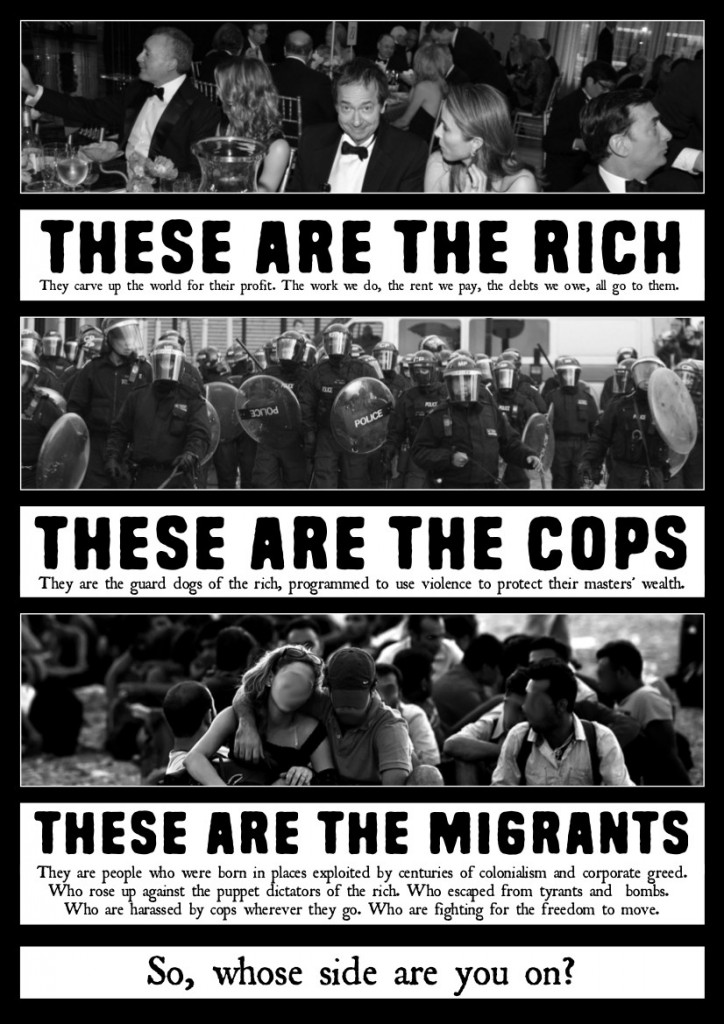

image from antiraids network

1. Introduction: what is immigration policy for?

It doesn’t “work”

UK immigration policy is usually presented by politicians in terms of one objective: “getting control” over the flow of immigrants. But one thing is apparent: if the objective is control, immigration policy doesn’t work.

Most obviously, numbers have not gone down. Net migration to the UK has been positive in every year since 1994, and over the current target of 100,000 in every year since 1997, peaking at over 300,000 in 2014 and 2015. Recent decline has not been caused by Home Office measures but by one big unanticipated factor – Brexit scaring off EU immigrants.

As an example, let’s take a mainstay of Home Office Immigration Enforcement within the UK territory – raids on people working illegally. The Home Office carries out around 6,000 workplace raids each year, and makes around 5,000 arrests, half of which lead to deportations. For obvious reasons, there are no reliable figures on numbers of illegal workers – but reasonable estimates put the figure at least in the hundreds of thousands. Immigration Enforcement thus has little impact on the numbers of “illegal workers”.

This point is widely acknowledged, in private, by Home Office staff from top to bottom. The Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI)’s 2015 report on “Illegal Working” features candid interviews with both frontline officers and senior civil servants. To quote a typical example:

“A senior Home Office manager told us that there was a general awareness within [Immigration Enforcement] that enforcement visits encountered and removed only a small proportion of offenders and that IE would never have the resources to resolve the overall problem. They described it as ‘not a realistic working model’. Another senior manager commented: ‘It’s a business model that hasn’t moved on’.” (para 4.7)

New research from the University of Oxford’s COMPAS unit looks at this issue in greater depth. The “Does Immigration Enforcement Matter?” research project conducted numerous interviews with Home Office staff of different grades. The overwhelming picture is of an institution with extremely low morale, where officials are well aware of their lack of impact.

The current “Hostile Environment” policy, first introduced by Theresa May as home secretary, could be read as a new approach seeking to make immigration enforcement more effective whilst recognising the Home Office’s limited resources. The rationale: if it’s not possible to round up all the illegals, then creating “a really hostile environment for illegal migrants” through limiting “access to services, facilities and employment by reference to immigration status” will help control migration by acting as a deterrent. As they feel the chill, unwelcome people will opt to leave the country independently or through paid “voluntarily return” programmes. Others, hearing what Britain has become, will decide not to come in the first place.

As there are not enough Immigration Enforcers to create sufficient hostility alone, the policy aims to enlist ordinary citizens into a volunteer army of informers and collaborators. School teachers, doctors, nurses and hospital receptionists, charity workers, registry office staff, bank clerks, as well as employers, landlords and letting agents, supply Big Data to better guide enforcement operations. And they also take over enforcement roles themselves by directly policing access to housing, healthcare, education and bank accounts.

The Hostile Environment is dramatically reshaping aspects of Britain’s civil society – but how successful is it really as an immigration deterrent? Despite the rhetoric of “evidence led” policy, there are no official studies evaluating these measures’ effectiveness. The most comprehensive research on the subject so far is the COMPAS project noted above. Researchers also interviewed “irregular” migrants of different nationalities, asking about their experiences and perceptions of immigration enforcement. This research suggests that many migrants are certainly aware of such measures, and are affected by them – above all psychologically, living with high levels of fear and anxiety. But there is little evidence, so far, that this psychic pain actually pushes many people to leave.

Immigration enforcement makes people miserable. But miserable enough to return to situations of still more extreme poverty and insecurity, or war and repression back “home”? Hostility would have to be ramped up to a truly intense level to adequately deter people, in a world where the sub-minimum wages and other conditions of life accessible to many “illegals” in the UK are still preferable than those found in its former colonies or its warzones.

The UK’s ultimate “hostile environment” experiment is on the border in Calais. Here the British and French governments spend millions to make people’s lives a living hell – and still people keep arriving, their other choices being so desperate.

So what is it really for?

Why do Home Office politicians and bureaucrats keep pursuing immigration enforcement policies if they know they don’t work? Here are a few ideas:

- Ineffective policies are “better” than none at all. Policy-makers know that immigration control policies are weak instruments, but think having none at all would lead to an even worse outcome, i.e., even higher immigration. Immigration policy is like continually patching up a leaking building with half-useless tools.

- They just don’t have any better ideas. Home Secretaries and their advisers have to be seen to do something, and the best they can think of is to keep proposing new measures even while knowing they won’t succeed.

- Actually, immigration control policies do work – but the real objective is not what it’s officially said to be.

There may be some truth in all of these, but we’re going to concentrate on the third answer. Immigration policy makes a lot more sense if you judge it against different criteria than cutting numbers. That is: the effective aim is not actually to control immigration, but just to look like you are taking steps to control it. It is a spectacle, a performance, of control. So then we have the question: who is this performance aimed at?

“public opinion”

The immediate answer, if you listen to politicians talk, is “the public”. This is a standard line from policy-makers and civil servants: “we have to respond to public opinion”. This answer is common across the political spectrum. On the Left, it may be prefaced: “we don’t really oppose immigration, but …”

The story is: public opinion is inescapably in favour of strict immigration control, so all policy-makers need to start from this given, or face political suicide. But what, exactly, is public opinion? Who, exactly, is the public?

These terms are thrown around very lightly, but are actually very complex. In fact there are millions of people in the UK, with millions of different opinions. Nor are they all communicating with each other as part of one “public debate”. When politicians talk about “public opinion” they are not talking about this enormous diversity of views, but about those views they consider particularly important. In the next section we will explore the nature of “public opinion” on immigration in depth.

image from antiraids network

2. From Public Opinion to Target Publics

Opinion polls give a crude perspective on the range of views people hold, and are skewed towards certain types of people who participate. More fundamentally still, individuals’ thoughts, feelings, motivations, can hardly be summed up in multiple choice boxes. But still, polls are the only tools we have for trying to understand massive numbers of people’s attitudes. We’ll start with an overview of some key facts from immigration opinion surveys.

2.1. most people say immigration should go down

The polls are consistent on one point: most UK citizens say they want immigration to be reduced.

A recent long-term study of immigration attitudes by major polling firm Ipsos MORI, “Shifting Ground”, finds that “Britons are becoming more positive about immigration”. In March 2015, 43% people said that immigration had a negative impact on Britain, and 33% said a positive impact. But by October 2016, those proportions had reversed: now 43% though immigration was positive, opposed to 32% negative. But despite that, 60% still said it should be reduced – little different from 62% in 2015. In fact, according to Ipsos MORI:

“this is a common feature of immigration attitudes in the UK over many decades: despite significant ups and downs in actual migration figures and how top of mind a concern it is, our review of historical attitudes to immigration shows that there are always 60%+ who want immigration reduced.”

2.2. it matters – but how much?

We need to separate two points: what people feel – or say they feel when asked by an interviewer; and how much it actually matters to them.

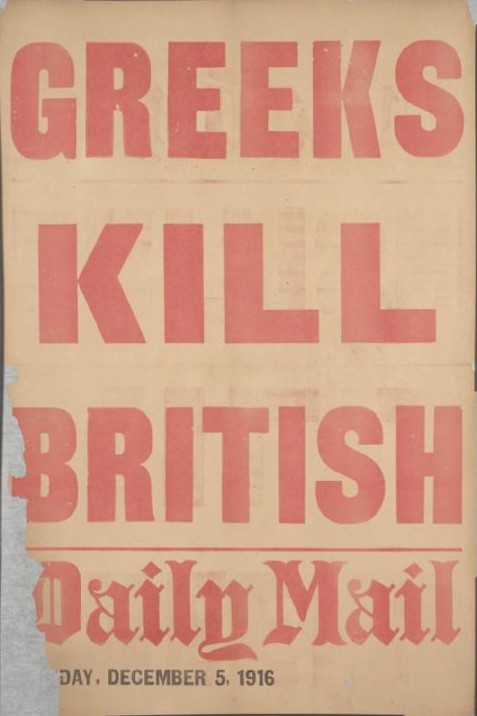

Immigration scares are nothing new to Britain. But the current wave of anxiety over immigration really started around the year 2000. Ipsos MORI has carried out its Issues Index every month since the early 1970s. The survey asks people two questions: “what they believe the biggest single issue facing Britain is” and “other big issues they believe are facing the country.” Another Ipsos MORI report from 2013, called Perceptions and Reality: Shifting Public Attitudes to Immigration, studies the results over almost 40 years.

For most of that time, less than 10% of respondents mentioned immigration as an issue. This changed in the “immigration panic” at the end of the 1970s: over 25% named immigration as important in 1978-9. But that panic didn’t last, and the figure fell back below 10% in 1980, where it stayed for 20 years, apart from a brief spike in 1985. Health, defence, crime, and above all “the economy” remained the traditional political concerns.

In 1999, with more people around the world leaving the countries of their birth, the numbers of people concerned about immigration in Britain started to jump, and since 2001 at least 20% of respondents have named immigration as an important issue in almost every monthly survey. So far, the peak of the new panic was in 2006-2008, where over 40% regularly did so. In 16 months in these three years, immigration was the number one issue named. Then in 2009, with the credit crunch and recession, “the economy” retook its traditional position as top issue. But immigration has stayed up there, with a recent peak of 38% in August 2013. As of December 2017, the figure had dropped to 21%. One reason is that a new issue, Brexit, has taken over as the top concern.

2.3. it’s complicated

So what has caused that jump in immigration anxiety? An obvious explanation might be: because immigration has been going up. And that’s certainly a factor: the polling data indeed shows a clear positive correlation between immigration levels and the “Issues Index”.

But it’s not the only factor. For example, the overall immigration level doesn’t explain why things started to move around 2000, when immigrant numbers were already rising before this. Or why there were previous shorter “panics” in the 1970s and 80s, when immigration was much lower than now. Also, looking at opinion polls across Europe, Ipsos MORI point out that there “is virtually no relationship between levels of net migration and concern across the EU27 countries (and the same is true for every measure of stock or flow of migration or immigration that we examined).”

It’s not just that people are more worried when there is more immigration. There are other important factors at play here.

2.4. a few people are very worried indeed

Another measure of immigration concern is the “MPs’ Survey”, where MPs record the “postbag” of issues brought to them by constituents. This shows an even steeper rise of concerns about immigration. In the mid-80s, less than 10% of issues raised by constituents were about immigration. This began to change in the late 1980s, and in 1992 over 20% of issues were migration related. Since 2002, at least 40% of all constituent contacts with MPs have been about migration. In 2006, at the highest point, just under 80% were about immigration.

We can note two points here: constituent concerns started to escalate some years before the “general” attitudes surveyed in the Issues Index; and then they climbed to much higher levels. While around 20% of the overall population now generally think of immigration as a political issue, a smaller segment have become particularly vocal, including making the effort of going to their MPs.

2.5. who’s worrying?

older people

Concern about immigration is strongly linked to age. All “generations” have become more concerned since the 1990s, but, for example, in 2013, 40% of people born pre-1945 saw immigration as an issue, compared to 38% of “baby boomers” (born 1945-65), 30% of “generation Y” (1966-79), and only 22% of “millennials (1980-2000). It is also extremely relevant here that older people are much more likely to vote – and to contact their MPs.

lower middle

Immigration anxiety is also related to social class, but the effect is less strong than with age. In fact, until 2000, Issues Index surveys saw minimal differences between social classes in migration attitudes. Since then, there is a clear trend of “skilled manual workers” (called “C2”s) being particularly concerned about migration – an extra 5% or more people in this group are likely to name immigration as an issue. Differences amongst other classes are smaller and less consistent, although concern tends to be lowest at the extremes – “professionals” (A) and “unskilled workers” (E). Very roughly speaking, immigration worry is strongest amongst the lower middle and skilled working classes.

geography

77% of the total population agreed, when asked by pollsters in 2013, that immigration should be reduced a little or a lot. This was true of the majority of white British people in all areas of the country – but the proportions varied a lot by area. The lowest agreement was in areas classed by pollsters as “cosmopolitan London” – where 68% agree. This compares to 85% of white British people living in “new, large freestanding and commuter towns”, “migrant worker towns and countryside” and “low migration small towns and rural areas”, and 84% in “industrial and manufacturing towns”. In “asylum dispersal areas” – which are impoverished areas predominantly in the North and Midlands – 83% agree with reduced migration; and 67%, the highest proportion, think it should be reduced “a lot”.

immigrants can also be anti-immigration

Anti-immigration feeling also exists amongst immigrants. It is closely correlated to how long people have lived in the UK. 70% of immigrants who arrived before 1970 also agreed that immigration should be reduced; only 28% of those who arrived after 2006 did.

segmentation analysis

To bring together some of these demographic factors, pollsters use a technique called “segmentation” analysis, which involves identifying loose groupings of people who tend to share both similar characteristics and similar views. We will mention two notable segmentation studies.

In 2013 the Conservative pollster Lord Ashcroft conducted a detailed study on immigration opinion based on a poll of 20,000 people, called “Small Island: public opinion and the politics of immigration”. This broke down interviewees into seven “segments”. At one end of the spectrum is a “universal hostility” segment (16% of respondents); at the other a “militantly multicultural” pro-migration segment (10%).

In between, there are two segments who may not be outspokenly pro-migration, but don’t see it as an important issue. One is the “urban harmony” (9%) grouping, mainly young and ethnically diverse, who frame their issues in terms of the economy, jobs and public services, rather than immigration. The other are the “comfortable pragmatists” (22%), well-educated and well-off people who don’t particularly feel migration either as a threat or a benefit to them.

The other three segments all have concerns about migration, but for different reasons. The “cultural concerns” group (16%) are usually older people, often owner-occupiers, who talk about immigration in terms of social change and a threat to the British way of life. The “fighting for entitlements” group (12%), also generally older than average and with less education, are concerned about pressures on public services. The “competing for jobs” segment makes up 14%.

Ipsos MORI’s analysis in “Shifting Ground” is broadly similar. It identifies four segments:

- A strongly “anti immigration group” (28%), often opposed to migration on numerous grounds, including “immigrants taking away welfare services and jobs”, but also because they are “nostalgic for the past”. “Older, lower levels of education. Social renters. Highest support for UKIP. Voted heavily to Leave.”

- A relatively hostile “Comfortably off and culturally concerned” segment (23%) These “don’t feel personally threatened by immigration” but are worried about its impacts on a changing society. “Oldest group, retired, most likely to own house outright. Highest support for Tories. Split on EU referendum vote.”

- The “Under Pressure” 25% may say that “other people get priority over them for public services and immigrants get priority over jobs”. But immigration isn’t the main thing they blame – their biggest concern is “the economy”. “Youngest age group, highest number of part time workers.” “Politically disparate and highest group of undecided voters. Marginally more Remain than Leave.”

- The “Open to Immigration” segment (24%) is “Well educated, highest group of private renters. Highest group of Labour supporters. Mostly voted Remain.”

image: asylum dispersal areas – G4S accommodation in Sheffield, by John Grayson

2.6. cultural vs. economic concerns

The segmentation analysis suggests three kinds of ways that people worry about immigration:

- Some people have strong anti-immigration feelings in general. They may cite a range of reasons for concern, including both “cultural” and “practical” or economic issues. But their anti-migrant feeling goes deeper than any of these particular reasons.

- Some people’s anti-immigration worry is closely linked to “cultural concerns” – they feel immigration as a threat to an accustomed “way of life”. This is particularly true for older white British people. Many people who fear immigration in this way are comfortably off, and don’t personally feel economically threatened by immigration.

- Some people may worry about economic or practical impacts, e.g., feel they have to compete with immigrants for jobs, housing or benefits, without fearing cultural change from “diversity”. These kinds of concerns may be heard from younger people who live in diverse urban areas, and may come from migrant backgrounds themselves.

One important point, noted by Ipsos MORI, is that “cultural” worries about immigration seem to be stronger than “economic” worries. Many inner city workers who feel themselves directly competing with migrants tend to be less anti-immigration than “comfortably off” suburbanites who worry about migration as a threat to a way of life. When asked, they may agree immigration should be reduced. But they are more likely to think of “the economy” as the main problem.

This point is also argued by Scott Blinder of Oxford University’s Migration Observatory in a 2011 briefing on “UK Public Opinion toward Migration: Determinants of Attitudes”. He writes:

“At least three basic explanations of attitudes toward migration have been researched extensively:

- Contact theory holds that sustained positive contact (i.e. friendships) with members of other ethnic, religious, racial, or national groups produce more positive attitudes toward members of that group.

- Group conflict theory suggests that migrants or minority groups can appear to threaten the interests, identities, or status of the majority (as a group), and that those who feel this sense of threat most acutely will be most likely to oppose migration.

- Economic competition theories suggest that opposition to migration will come from native workers who compete with migrants with similar skill sets, or (conversely) from wealthier natives who feel (or perceive) a financial burden for tax-payers if migrants use public services such as hospitals, schools.”

Reviewing the survey evidence and literature at that point, Blinder concludes that: “Evidence is quite strong for the first two theories, and mixed for the various economic explanations.” In particular:

“Subjective perceptions—of one’s own economic security and of migrants’ impact on jobs, wages, and the costs of maintaining the welfare state—do seem related to anti-migrant attitudes. But these subjective perceptions are only loosely related to actual individual economic position.”

image: middle England – the 1922 Daily Mail model village at Welwyn Garden City, by Steve Cadman CC license

2.7. whose problem?

The Ipsos MORI Perceptions and Reality report makes another very important, and related, point. Most people who think immigration is a problem don’t think it is a problem for them personally, or for their local area.

Surveying by Eurobarometer, cited in the Ipsos MORI report, asks people for their two top issues “nationally” and “personally”. In various surveys over 2008-13, between 18% and 32% of people in the UK named immigration as a national issue; but only between 6% and 10% said it was a personal issue. Similarly, across the EU27 countries, between 7% and 9% named immigration as a national issue, but never more than 4% as a personal issue.

A similar picture emerges from some of Ipsos MORI’s own polling between 2006 and 2010. This asked the question:

“Overall how much of a problem, if at all, do you think immigration is in Britain at the moment? And how much of a problem, if at all, do you think immigration is in your local area at the moment?”

Consistently across this period, they found a dramatic 50% gap between the two answers. At the highest point of concern, in November 2010, 77% said they thought immigration was a problem in Britain. But only 26% thought it was also a problem in their “local area” as well as nationally. (8% thought it was a problem locally but not nationally, and 22% neither.) As the pollsters say, “these types of gaps exist in other policy areas, such as crime and health services – but they are particularly striking with immigration.”

Many people’s worries about immigration do not arise from personal experiences, or from what they see in the areas where they live. For many, we could say, immigration worry is not about concrete problems we experience directly impacting us or those around us. It is something more abstract: a fearful sense of “cultural change”, a narrative of loss and threat, felt to be affecting “the country” as a whole.

2.8 summary

Most British people, when asked by pollsters, say they think immigration should be reduced. But this doesn’t mean that most people think of immigration as a significant problem.

Some people are really concerned about immigration – and their number has been rising, from less than 10% of the population before 2000, to more like 20% now. Some of these people feel very strongly, and are very vocal. Also, they are often people who are likely to vote, and to contact their MPs.

We can think of two main groupings of people who are most likely to worry about immigration – two anti-migrant minorities. Both are typically older and white. But their social circumstances may be quite different:

- Typically older, white, working class people hit hard by poverty and social tension, often living in run-down neighbourhoods in the North or Midlands with large migrant populations, including “asylum dispersal areas”. Excluded from the economic consumer dream, they may feel directly impacted by immigrants, identifying them as a threat to jobs, services, benefits. But they also feel immigration as a “cultural concern” – a feeling reinforced by personal experience of seeing their neighbourhoods changed by new arrivals. Economic and cultural concerns may build together into a deeply felt “universal hostility” towards immigrants.

- Typically older, white, middle class people, often living in suburban or rural areas. They may be more or less comfortably off, and do not perceive immigration as a personal threat – maybe they rarely meet migrants except those serving them a curry. But they feel anxiety about immigration as a cultural concern, a threat to their values and identity.

Some of those who worry about migrants are excluded from mainstream society and blame migrants for their troubles. Others are comfortably included. The common factor across these two groupings is not economics, or personal experience, but a more generalised anxiety about migration as a cultural threat. Where does this anxiety come from?

image: Tony Blair, by World Affairs Council CC license

3. Politicians: immigration and elections

Politicians live off the approval of others. In the next three sections we look at three ways in which the quest for approval shapes immigration policy. First, in this section, we will see parties seeking the support of key “target publics” in election campaigns. When it comes to immigration, we will see that the target voters politicians look to in election campaigns are above all the anti-migrant minorities noted above. At the same time, politicians are also deeply concerned with approval from their own peers, and from the media, as they seek to advance their careers. We will look at these issues in the next two sections.

3.1 Election strategies: target voters

No policy is going to please everyone. But politicians don’t need to please all the people – just those whose support matters for their success. By “target publics” we mean groupings of people whose approval policy-makers are aiming to win, when they make policies.

How aware are politicians of who they are targeting? This is an interesting question, though not one we can tackle here. As a rough thought, we can suppose that much of the time effective politicians have an intuitive idea of the target groups they need to reach. But there is at least one time when politicians need to identify target publics much more precisely: during election campaigning. In modern election campaigns, intuition and unguided prejudices are supplemented by more sophisticated techniques. Understanding election targeting can at least give us a start to understanding “target publics” in general.

Who are the decision-makers?

Here there is no better guide than the (in)famous “wizard of Oz” Lynton Crosby, known in the UK for the 2005 and 2015 Conservative election campaigns, as well as Boris Johnson’s mayoral victory. However, Crosby’s techniques are by no means exceptional, and similar approaches are now the norm across the political spectrum. As Crosby explains in a “campaign masterclass”, the core of any successful campaign is identifying the crucial decision-makers. “Who is the target, who matters? What matters to them? Where are they? How do you get to them?” Most basically, this means identifying three types of voters:

- the base: those you can rely on to support you

- the antis: the opposition’s base

- the swingers: people who could be persuaded either way

Campaigning is all about maximising the use of limited resources: money, activists, and time. None of these should be wasted on trying to persuade committed antis – the best you can hope for is to discourage them. So the campaign consists of, first, “locking in” the base; second, targeting those voters identified as most likely “swingers”. In the UK, those swingers are particularly important in so-called ‘marginal’ constituencies.

For example, in the 2015 UK general election the Conservative “40/40” strategy identified 40 defence seats, the Tory marginals where they needed to lock in existing voters, and 40 attack seats identified as potential swings to the party. The bulk of the party’s “ground” campaign – including thousands of bussed-in canvassers, local advertising and targeted direct mail-outs – was directed at just these 80 seats.

A massive data gathering operation, planned two years before the actual election, involved door-knocking not just to classify every voter as pro or anti-, but using a ten point questionnaire to make a detailed profile of each individual. Unpublished opinion polling continued throughout in the 80 seats, while information collected in-house was supplemented with commercial databases, including from the big credit rating and consumer profiling corporation Experian.2According to one account:

“Behind closed doors, [chief campaign pollster Jim] Messina boasts that he has 1,000 pieces of data on every voter in the U.K., one admiring Tory official revealed. […] Messina knows where every target voter shops, what they buy, how they travel to work — and much more besides.”

All of this data was crunched to provide a highly detailed picture of the key voter “segments” to be targeted. These targets were then hit with precise messages, differentiated both in terms of issues and of delivery (e.g., email, phone, text, hand-signed letter, doorstep visit).

As many noted after the 2015 result, this local propaganda effort went largely unnoticed by London-based media pundits – and by many opinion polls. They saw only the nationwide “public campaign”, or “air war” – the impact of big politicians’ speeches and television appearances, the famous Saatchi billboards and national advertising campaigns. They missed the “ground war” taking place “below the line”. While the public “broadcasting” campaign set the main campaign messages, an equally crucial role was played by “narrowcasting” which didn’t talk to one great “general public”, but to highly targeted segments in specific marginal constituencies.

(Another increasingly important form of “narrowcasting”, much in the news due to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, involves the use of facebook and other social media data. But we shouldn’t forget that this is just one aspect of the political use of Big Data.)

Differentiating issues

Crosby is famous for insisting that parties focus on just a small number of key issues – “scrape the barnacles off the boat”. Although this stripped-down messaging can misfire – as in the 2017 election where Theresa May looked like a vacuous robot endlessly repeating her “strong and stable” mantra. Crosby gives a four point test for identifying issues to campaign on:

Salience: “is it out there and people are talking about it”?

Relevance: “is it personally relevant, [does] it relate to people and their lives”?

Differentiation: can you use it to “set yourself apart from your opponent”?

Actionable: it lead people to want to vote a certain way.

Connecting this to the points above, the issues must be ones that matter to your specific target publics. So the campaign strategy asks: what issues are these target voters talking about, and what issues do they feel emotionally connected to? And it’s important to remember here that “there are lots of things people disagree or agree with but have no influence on people’s vote.” E.g., people may agree immigration is too high, but is this something that will bring them out to vote?

Beyond this, an issue will only work if you can use it to differentiate from the opposition, to say you’re the ones who are on the targets’ side on this – unlike the other lot. The aim is to downplay or “minimise points of differentiation on issues where you are weak”, and “establish differentiation on your terms”, highlighting the issues that make your story stand out.

Of course, a campaign may have a number of different target groups, each with different issues. “These days you will get caught out”, says Crosby, if you try to tell completely different stories to different groups. The trick is to use the public “broadcast” campaign to “set up your overall position” with “messages designed to appeal to everybody”. And then use the targeted “narrowcast” campaign to direct more “fine tuned and relevant messages to particular groups”.

Finally, besides manifestos and campaign literature, there are also more subtle ways parties can flag up their issues and stories. For example, Crosby advises focusing only on “positive” campaigning in official propaganda. Negative attacks on opponents are best done by using “proxies”, i.e., let other actors, such as friendly media outlets, raise the stories and issues that fling mud on the opponents, while your own hands stay looking clean.

Now we can look at some of these strategic basics in action over the last 20 years of immigration politics.

3.2 UK immigration politics 1997-2017

When Blair came to power in 1997, immigration was not an issue on either of the main party’s agendas, nor did it feature in “public opinion” lists of political issues. Labour’s pitch was based on five pledges concerning education, the NHS, crime and punishment, youth employment, and frozen tax rates. In so far as Labour had an immigration narrative, it was to ape Tory rhetoric: then shadow home secretary Jack Straw famously said in 1996 that “not a cigarette paper” should separate the two parties on immigration.

The climate began to shift from 1999, beginning with fevered media reporting of Sangatte and the “asylum crisis”. Polling on immigration as an issue for “public opinion” began to rise. Yet in 2001, Labour effectively ignored immigration as an election issue, focusing again on an updated list of the same five issues. In 2005, for the first time immigration was explicitly added as a sixth election pledge, under the slogan “Your country’s borders protected.”

It made good sense for Labour not to flag up immigration as an electoral issue. It was one of the few policy areas where opinion polls saw the Tories firmly ahead of Blair. The election strategy was thus clearly to “neutralise” on immigration and shift attention onto stronger ground.

However, beyond electioneering, Labour Home Secretaries did make clear efforts to respond to anti-immigration public opinion with a quick succession of tough new laws. These were: the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999; the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (following the 2002 “Secure Borders, Safe Haven” white paper); Asylum and Immigration (treatment of claimants) Act 2004; Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006 and Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009.

This pace of successive anti-migrant laws was unprecedented in UK history. But the most obvious feature was that they focused on a particular category of migrants: asylum-seekers. In essence, they made life ever tougher for refugees by making asylum claims harder, removing support, and expanding the detention regime – funded, of course, by Labour’s favoured PFI schemes. Besides asylum, they also added in headline-grabbing measures against “sham marriages”, “foreign criminals”, or “terrorists” seeking asylum.

The Labour government’s immigration policy might be summed up quite succinctly:

- true to neoliberal principles, Labour remained relatively liberal on immigration seen as economically beneficial: e.g., workers, European free movement, and the booming foreign student business;

- meanwhile, in an attempt to assuage anti-immigration sentiment – that is, to neutralise immigration as an issue for opponents – Labour made spectacular attacks on asylum seekers, who were migrants seen as not of economic value, and so available scapegoats.

This double approach did begin to change towards the very end of the “New Labour” period under Brown. The party began to move away from its more overt immigration neoliberalism with the “Points Based System” for non-asylum entrants, rolled out from 2008.

Conservative opposition: “are you thinking what we’re thinking?”

Despite the attacks on refugees, Labour’s overall immigration policy was still seen as too “soft” by some voters. In the 2001 and 2005 general elections, Conservative challengers William Hague and Michael Howard attempted to capitalise on this by deploying immigration as an election issue.

In 2001, Hague made immigration – and the asylum scare in particular – one of his top three issues, alongside tax cuts and Europe (“saving the pound”). But the attempt was notably unsuccessful in making inroads against the Blair machine.

In 2005, Howard again played the immigration card, alongside crime and hospitals. The campaign was run by Lynton Crosby, hired after a notable run of successes for the Australian right-wing Liberals, which had centralised anti-migration anxiety. The slogans “are you thinking what we’re thinking?”, “it’s not racist to impose limits on immigration”, epitomised the “dog whistle” tactic – framing messages in a way to chime with certain target publics, whilst avoiding open hostility that might offend others.

Polling suggested that the Tories had a strong lead over Labour on immigration. But Labour still beat them on all the other main issues: by a long way on health and education, and even slightly at that point on traditional Tory issues of tax and crime. And immigration was only fourth on the list of “salient” issues. It may well have made sense for the Tories to flag immigration: it was one of very few issues where they clearly stood out from, and beat, Labour at that point. However, many commentators argue that the strategy only really reached the Conservatives’ own base, rather than the swing voters they needed to win over.

Conservatives under Cameron: detoxifying

After 2005 the new leader, David Cameron, tacked back to the centre ground. The plan was to target “small l liberal” swing voters, which required “detoxifying” the “nasty party” by rolling back on the right-wing messages. The 2010 election campaign was fought on the economy, again a winnable issue for the Tories after the 2008 crash. The 2015 campaign continued the economy and austerity story, but became largely a full-on assault on Ed Milliband’s weakness, from his bacon sandwich issues to his potential dependence on a coalition with the SNP.

However, as Tim Bale and co-authors write, Cameron managed to “have his cake and eat it” on immigration in the run-up to 2010. Leaving immigration out of the broadcast campaign package helped reassure the “small l liberals”. But in fact the party could still gain from the immigration issue, largely thanks to “proxies” who would flag it up for them. In the “long campaign” before official electioneering, backbench Tory MPs did the job of making more outspoken anti-migrant comments, which could then be gleefully amplified by right-wing media, without implicating Cameron’s leadership.

In the 2010 campaign itself, the notable example was Bigotgate, when Gordon Brown was unwittingly recorded calling a pensioner who had complained to him about immigration numbers a “bigoted woman”. With the media frenziedly running the issue, there was no need for party leaders to introduce it themselves. Thus the Tories managed to attract anti-migrant voters, whilst at the same time not alienating “liberals”.

In the 2015 election, there were further reasons for the Conservatives not to flag immigration. Key to the Tories’ aim of winning an outright majority was “decapitating” Lib-Dem support, and the main battleground switched to Tory/Lib-Dem marginals – meaning even greater need to attract “small l liberals”. On the other flank, UKIP had become a real electoral problem, and it was now they who “owned” immigration among many target publics. Not only because UKIP would always use tougher rhetoric, but also simply because the Conservatives were now in government, and so faced the inevitable fact that they can’t actually keep migration “under control”.

Labour in opposition: apologies

Labour did not have to worry too much about its immigration weak point so long as it led the Tories on other more salient policy issues, including the economy. After 2010, with its economic reputation smashed, it no longer felt this luxury. Under Milliband, the party took a new approach, symbolised by its infamous “controls on immigration” branded mugs: it would embrace a “tough” stance on overall immigration, which involved apologising for its previous “mistakes”.

In the wake of defeat, Labour strategists were finally waking up to the idea that the party needed to reconnect with working class voters taken for granted by Blairism. Groupings such as Prospect, the Fabian Society, and the Blue Labour tendency, were influential in arguing that the way to do this was to cleave to “socially conservative” and nationalistic values.

This attitude was galvanised by the threat from UKIP, growing in the build-up to the 2015 election. Although so far UKIP had done more damage to the Conservatives, a 2014 Fabian Society report identified five Labour seats as under direct threat from UKIP victories – and, more importantly, a greater number where losing votes to UKIP would let in Conservatives.

the battle for UKIP voters

Throughout recent decades, the mainstream parties have worried about losing votes on immigration to smaller parties emerging from the “far right”. In the 1970s, it was the National Front; in the 1990s, the British National Party; and recently, UKIP. Although UKIP’s official main issue was independence from the EU, their growth in support in 2010-16 largely came from positioning themselves as an anti-immigration protest vote. In the run-up to the June 2016 referendum, immigration was the number one reason people gave for deciding to vote Leave.

Ahead of the 2015 election, losing votes to UKIP was a crucial issue for both Conservatives and Labour. Labour’s strategy guidance on “Campaigning against UKIP”, leaked and published by The Telegraph, makes clear that “Immigration is the issue people most often cite when explaining support for UKIP.” Like the Conservatives, Labour based its “ground war” on the Experian Mosaic database, alongside in-house research, and the document analyses UKIP’s support using Experian categories.

According to this analysis, UKIP’s main target public was “older traditionalist” voters, who make up approximately 23% of the population. This category is broken down into four Mosaic groups: D “small town diversity”, E “active retirement”, L “elderly needs” and M “industrial heritage”. D and E are more affluent segments of older people who usually tend Conservative. That is, they are the key “comfortable but culturally concerned” demographic of anti-migrant “public opinion” we looked at in Section 2.

L and M are older, white working class people, classic Labour targets – that is, the other key anti-migrant demographic we looked at. The absolute model of a UKIP switcher was “White, Male, Aged 47 – 66, Further education – not university educated, Mosaic Type 42 – ‘Worn Out Workers’, Lives in Yorkshire.” In addition, Labour identified two other Mosaic categories – called J “claimant cultures” and I “ex-council communities” – of younger traditionally Labour voters who were also in danger of UKIP’s lure.

These four Mosaic categories became Labour’s main target publics in seats identified as UKIP threats. Campaigners were instructed to “listen to their concerns” and explain Labour’s new hardline policies on immigration, then steer conversation onto “our key policies”. In order not to alienate pro-migrant base voters, a tough line on immigration was not a major part of the “broadcast” message, but only flagged to specific target publics as part of the “ground war”.

To sum up: Labour’s campaigning effort in 2015 was largely directed at the particular demographics we discussed above in Section 2. The “public campaign” was not explicitly fought over immigration, but a large part of the “ground war” was fought over the hearts and minds of those target publics seen as most anti-migrant.

Labour’s 2015 campaign was a notable failure – although, as it turned out, the main problem was not UKIP but the Tories hoovering up Lib Dem seats and the SNP decimating Labour in Scotland. And by the 2017 election, the UKIP bubble had burst, while Corbyn’s Labour managed to make an unexpected comeback. The new tougher line on immigration stayed in the manifesto, which promised to outdo the Tories in hiring 500 extra border guards.

3.3 Summary

Conservative immigration policy in 2010-18 in many ways mirrors Labour policy in 1997-2010. In both cases, it makes sense for the governing party not to explicitly flag immigration as a campaign issue. There are obvious reasons:

- Whatever its rhetoric, no modern government working within the reality of a globalised economy is actually able to get immigration “under control” – certainly not to the satisfaction of anti-migrant media and “public opinion”;

- Both governments are vulnerable to attacks from the right on immigration – Labour from the Tories and UKIP, the Tories from UKIP. This is because both parties have important target publics who fall into the key anti-migrant minority demographics discussed in the last section. For the Tories, these are the “comfortable but culturally concerned”. For Labour, excluded older white working class voters – those who the party rushed to try and win back with its “Blue Labour” turn.

- At the same time, neither party wishes to alienate its more “liberal” target publics by overplaying toughness against vulnerable migrants.

But it can help to neutralise its overall “failing” by taking action between elections. Although the government can’t actually “control” immigration, it can use policy to make spectacular attacks on easy scapegoats. Under Labour, this meant a spiral of ever tougher asylum laws. Under the Conservatives, the “Hostile Environment” policy against “illegals”. Attacks on these marginal groups won’t scare off too many “liberal with a small l” voters, but can – the logic goes – be displayed as signs of toughness to help assuage anti-migrant defectors.

To sum up: these policies are directed not at “the public” as a whole, but at particular “target publics” identified as key electoral demographics. Governments launch vicious attacks on scapegoat groups as a way of trying to assuage these anxious minorities.

image: David Blunkett by Policy Exchange, CC license

4. Politicians: Home Office agendas

The more immigration is a salient political issue, the more immigration policies will be directed by the overriding imperative of winning elections. But there are also other dimensions of immigration policy-making to consider. So long as they fit within the broader electoral baseline, Home Secretaries and their juniors also have scope to pursue their own agendas.

For example, in the high profile Operation Vaken “Go Home van” policy, the Home Office paid for advertising billboard vans to drive around migrant areas with the slogan “In the country illegally? Go home or face arrest.” This was a media-focused strategy headlined by the Immigration Minister (junior to the Home Secretary), then Mike Harper. From what we have heard anecdotally, the idea itself was first thought up by a Home Office civil servant, before being signed off by ministers. According to recent press revelations, Theresa May (then Home Secretary) discussed the plan by email while on holiday in Switzerland, and requested that the wording on the vans be “toughened”.

Junior ranks: “nobody likes us, we don’t care”

Policy formation within the Home Office is harder to study than electioneering: there is less transparency, and also less interest in the subject. Two recent academic research projects, COMPAS’ “Does Immigration Enforcement Matter?”, and the book Go Home, gained access and insights from lower level Home Office staff, but were largely rebuffed at policy level.

The authors of Go Home discuss the performative character of Home Office immigration policies, tracing the current approach back to a communications strategy developed under Labour Home Secretary John Reid in the mid 2000s. They write:

“a rebranding of the UK borders was undertaken in 2006, so as to amplify the sense of a national border, via flags, insignia, uniforms and other symbols. Meanwhile, a communications strategy aimed at getting more images of immigration raids into the media was launched […] this included inviting journalists along to witness raids, so as to divert media attention to the physical ‘toughness’ of the border, and away from the rhetoric and perceived elitism of politicians.”

The best known fruit of this strategy was the UK Border Force Sky TV series sponsored by the Home Office, which ran in eighteen episodes from 2008, and featured star narrators Timothy Spall and Bill Nighy. The series ended in 2009, but the Home Office continues to sporadically run stunts “embedding” TV crews and other journalists in raids.

As Go Home’s authors note, the Home Office faces a dilemma in its immigration PR strategy:

“While some interviewees suggested that keeping migration out of the news altogether was the ideal political scenario for the Home Secretary, the medium-term implausibility of this means that any Home Office needs to pay constant attention to the news cycle. […] On the other hand, given deep levels of mistrust in the government’s ability to manage immigration, even very tough messaging can backfire if it reminds the public of issues (such as illegal immigration) that have otherwise fallen out of the news cycle.”

The writers also point to “the context of the Home Office’s own exceptional status”:

“The ministry has been frequently mired in controversies and media attacks, leading it to be represented as a ‘political graveyard’ […] the department as a whole operates on a relentless communications cycle, which inculcates a sense of paranoia and watching one’s back. In addition to this, there are deep structural reasons why the Home Office encounters regular conflicts with other Whitehall departments, especially where the latter operate according to more liberal economic rationalities. For these reasons, one interviewee joked that the internal philosophy of the Home Office could be summed up by the well-known chant of Millwall football fans, ‘No one likes us, we don’t care’.”

Again, this view comes from further down the hierarchy. At the top, and most of all for the Home Secretary in person, the office is a notable power position. Far from being a “graveyard”, it is one of the senior ministries where politicians who distinguish themselves may go on to challenge for the Prime Minister’s job – as did current premier Theresa May. Other recent party leaders who made their names as home secretaries or shadow home secretaries include Tony Blair and Michael Howard.

tougher than the last

One useful research project on Home Office policy at the top is a 2014 PhD thesis by Lisa Thomas, which involved interviews with four Labour Home Secretaries – Jack Straw (1997-2001), David Blunkett (2001-4), Charles Clark (2004-6) and Jacqui Smith (2007-9) – about their policy-making and their relations with media. Although the research focuses on terror rather than immigration policy, there is clear crossover. At the same time as pushing through an unprecedented succession of new anti-asylum laws in the 2000s, these Home Secretaries pushed through a wave of five major terrorism laws in 2000-2008.

Indeed, it makes sense to see both sets of legislation as part of the same overall “security” agenda. David Blunkett himself makes this clear in his interview, where he discusses the asylum scare and the Oldham race riots of summer 2001 as building a heightened sense of insecurity in the UK ahead of the 9/11 attacks later that year:

“Immigration, subliminal fear of rapid change, threat to the ‘normal’ way of living, the instability that that causes, obviously has implications as to how people receive messages about other aspects of security and of what’s happening in the world. Coupled with the fact that we had just moved into an era of seven days a week, 24-hour news. We were also beginning to see people using the internet and mobile technology. All of those things came together at the same time.”

Blunkett reveals that he believed the Home Office had actually “got on top” of the asylum issue. However, a major concern was the “massive upsurge of the right across Europe”. He says:

“Some of us had been arguing that we needed to be aware of this, and not panic or pander, but actually get a grip to the point where people were secure in their minds that we knew that there was an issue to be addressed. Providing them with that reassurance was as much a part of the security, because it affected their psyche and the way that they saw things, as was the physical security.”

In short, the big motivation of Home Office policy, on both asylum and terror, was to provide a show of “reassurance” through toughness, thus warding off threats from the right. The pattern began at least with Blair himself. As shadow Home Secretary in 1994-7, Blair made his reputation politicising the murder of two-year old Jamie Bulger, as part of positioning himself as a tough guy responding to public anxieties about crime. As he wrote later: “Very effectively I made it into a symbol of a Tory Britain in which, for all the efficiency that Thatcherism had achieved, the bonds of social and community well-being had been loosed, dangerously so.”

Over the Blair years, Home Secretaries were a succession of tough guys taking up the cudgel shadowy ranks of national bogeymen, where asylum-seekers, then terrorists, joined criminals and paedophiles. When Jack Straw wasn’t tough enough to quiet the tabloids – despite policies including removing asylum seeker benefit payments, restricting trial by jury, etc. – he was replaced by Blunkett, who had boasted of making his predecessor look like a “liberal”. Both revelled in provoking outrage from those labelled “woolly-minded Hampstead liberals” or “airy fairy libertarians”.

Since 1997, there has been a rapid increase in the pace of lawmaking on crime, terror, and immigration. First of all, this is demanded by the overall domestic strategy at the heart of government since Blair: demonstrate toughness and control in the face of insecurity and vague threat. But also, it is demanded by the more specific career aims of Home Office ministers. The ministry provides a stage for politicians to make a name for themselves by posing as tough. To do this they need to show action: new even tougher laws, or other new policies such as the continual restructuring of the immigration agencies.3

Summary

As immigration becomes a high-saliency issue, policies must fit with the basic political imperative: win elections. But this leaves scope for Home Secretaries and their assistants to come up with their own ideas. Indeed, the two agendas support each other:

- governments need tough Home Office policies to neutralise electoral threats from the right;

- Home Secretaries want to look tough to grab headlines and make a name for themselves.

So both party electioneering, and Home Office positioning, lead politicians towards “spectacular” anti-migrant policies. At the base of all this, we could say, politicians are led by the need for others’ approval – not just from voters, but from their own colleagues, as they seek to advance their careers. And there is another crucial group whose approval politicians crave. We can’t fully understand immigration policy-making until we look at our next topic – the key relationship between politicians and the media.

5. Media and politicians: a dense ecosystem

In this section and the next we will look at two kinds of media interactions: between media and their “publics”; and between media and politicians. We will start with the various ways in major media contribute to the formation of policy. Much of this section draws on Aeron Davis’ 2007 book The Mediation of Power, which provides a valuable study of the relationship between UK politicians and media, based on interviews with 40 sitting MPs, plus also other ex-ministers and some political journalists.

- direct collaboration

To start with the most blatant cases: sometimes politicians and media collude to organise joint campaigns. This guarantees stories for journalists, and coverage for the politicians. Perhaps the most infamous example of this to become public involves the Blair government’s collaboration with the Sun on its anti-asylum campaigning. According to political journalists Peter Oborne and Simon Walters, the Blair government knew in advance that the Sun was planning an “asylum week” of attack stories in August 2003. An interview with David Blunkett was already scheduled ahead of the week, where he would announce “tough measures to crack down on asylum cheats”.

- heavy exposure

Most politicians are “news junkies”. “On average, MPs consumed four to five different news sources, including three newspapers, each day. Just over two-thirds listened to radio news and the same amount watched television news. A third used online news services.” Many have 24 hour news constantly playing in their offices.

In his interviews, Aeron Davis asked politicians: ‘What are your main sources of information when it comes to informing yourself about, and deciding where you stand on, political issues?’ “News media was the second most mentioned source by all interviewees with four out of every seven listing it.” It was most common source given by back-benchers, who don’t have a staff of civil servants to brief them. To quote one interview, with Sadiq Khan, now mayor of London:

“Obviously the newspapers are very important to me. I read habitually … and I try to keep up with what the latest thinking is. And then, if something’s referred to, I’ll go look up the original source … So those daily and weekly newspapers and magazines signpost me where to go.”

- media campaigns

Davis critiques a popular “stimulus-response” model of media influence – the idea that media raise an issue, then politicians jump – arguing that media influence often takes more subtle forms. This is not to say that it never happens. The most obvious cases of media influence are where several journalists, perhaps across several outlets, mount a concerted steam-rolling “campaign” to highlight an issue or call for a policy. “Most MPs” interviewed could “think of examples of when the weight of a media campaign had been responsible for initiating or altering new legislation and budgetary decisions”. Immigration was one of the issues named here – alongside casinos, dangerous dogs, or funding for schools and hospitals.

But perhaps even more than issues, media campaigns are often directed at individual politicians themselves. “Several [of Davis’ interviewees] also talked about media campaigns being the main driving force behind a ministerial resignation or sacking.” But also, ambitious politicians can get considerable career boost if they can become “favourites” of journalists and outlets who highlight their actions, champion their policies, and laud them with gushing profiles. Blair’s pact with the Murdoch press is the classic recent example, alongside the Daily Mail’s promotion of Thatcher – and, less successfully, Theresa May.

- anticipation effect

One of the more subtle mechanisms, and perhaps more important, is what Davis calls an “anticipatory news media effect”. That is, politicians take account of the likely reactions of media while shaping policies in the first place.

“Former government ministers and shadow ministers explained that discussions of policy were frequently linked to the issue of how the policy would play in the media. For many, in fact, this had bordered on media ‘obsession’. Almost every interviewee who had served in a cabinet or shadow cabinet since the late 1980s, talked in such terms.”

Ann Widdecombe, the 1999-2001 Conservative shadow Home Secretary who led on the asylum scare, says: “We never discussed a policy without discussing the media impact ever.” Labour’s Frank Field describes the Blair government as “obsessed” by media, saying: “It’s the number one priority. The number one priority [in 1998–99] was the media coverage because at all costs we had to win a second time . . . Never mind about getting reforms.” Former Conservative minister John Whittingdale similarly describes Tory leaders John Major and William Hague as media “obsessed”.

Whittingdale also explains how this obsession doesn’t just lead politicians to check or filter their own policy ideas. Rather, the need for media approval can drive policy-making from the outset:

“the concern was always how can we get coverage. And the only way you get coverage is by saying something new. And by saying something new you were having to announce something.”

Former Labour minister Chris Smith similarly talks about a media-driven “‘something must be done’ syndrome”. And Ann Widdecombe specifically talks about Conservative immigration policy in this way:

“Asylum was huge during our time… I don’t think the media actually dictated policy but it did create an atmosphere in which it was felt something had to be addressed. Something had to be done about it.”

- political go-betweens

One reason politicians pay such attention to media is as a main source of information about other politicians. Politicians exist in a viciously competitive micro-world, always wary of attacks from rivals – and keen to find ways to strike first. These rivals may be in their own party, as well as on “the other side”. Big media provide the bulletin board, as it were, where politicians read about each others’ actions and announcements – and get a sense of each others’ plans and positionings.

“A quarter of MPs also stated that news was a way of gauging what others, either in one’s own party or in rival parties, were thinking on issues. Some also recounted that they often attempted to work out who the political sources of stories were and why they were sourcing the story. In effect, news media aided MPs in their attempts to interpret ‘feelings’ or trends in opinion within the parties themselves.”

In addition, as Peter Van Aelst and Stefaan Walgrave argue, the media is not just an information source for politicians to keep track of “the debate”, but also itself a primary arena where the game takes place. Politicians use media to make public announcements, and also more subtle signals – off the record comments, leaks, etc. Some is targeted at “the public”, but much at the other players.

- on the team

The remarks so far present politicians and media as two separate “teams” of independent actors. But in fact the lines are much more blurred, as the Davis study shows. First of all, politicians are in very regular contact with journalists.

“In all, just over two-thirds talked to journalists, on average, at least once a day, and usually several times a day. At busy periods some said they could have between 10 and 20 conversations with journalists in a single day.”

Some MPs present the relationship as a close functional symbiosis: journalists need stories every day, politicians need to get their messages out. So politicians need to keep journalists close because, as Iain Duncan Smith puts it, “you want to be able to feed them with your information.”

Some of the MPs Davis interviewed go further. “Many used terms like ‘friend’ or ‘colleague’ and would meet for social as well as professional reasons. Others referred to relationships as part of ‘alliances’ or ‘coalitions’. In all these cases it seemed clear that journalists were very much part of the policy networks that evolved within parliament”.

The political journalists he interviewed were still more explicit on the nature of this relationship. Politicians don’t just anticipate media responses, but while making policy many actively consult with journalists. They may cultivate a number of close relationships with influential columnists and political commentators, whom they value for their analysis and “inside knowledge”.

For example, Guardian columnist Polly Toynbee who says: “people are very keen to talk [to me] about policy when they’re sitting there all day wondering how to make their particular department work better.” The Telegraph and Daily Mail commentator Simon Heffer says: “People in the last Conservative administration did so [consulted me] all the time”, adding “I had friends who were well known to be sympathetic to the Labour party, who were often consulted by Conservative ministers.”

Politicians and political journalists occupy a shared micro-world based around Westminster. They work on the same issues, share information, share social environments. There is continual crossover between the two professions, and through the in-between category of “special advisors”, press officers, PR gurus, etc. It may often make sense not to think of them as on two opposing teams, but the same one.

- Quid pro quo

Another possible form of media influence is not mentioned by Davis or his interviewees, and it would be hard to gauge its extent. As in other workplaces, gossip swirls in and around the Westminster bubble, and much information is widely known that doesn’t get into print. Sometimes this may be for legal reasons, e.g., in the case of the numerous public figures with “super injunctions”. Other times, due to editors upholding “gentlemen’s agreements” – or purposefully holding back information in order to build and maintain the relationships on which Westminster thrives.

For example, in 2016 Davis’ interviewee Whittingdale was sacked as culture minister, responsible for media regulation, after his relationship with a sex-worker was eventually exposed. The story had previously been investigated by four newspapers, from The Sun to The Independent, but all held off publishing. The Hacked Off campaign group has alleged the newspapers withheld the story whilst Whittingdale was making media-friendly moves on press regulation.

Summary: mediapolitical ecosystem

Politicians pay enormous attention to media. Davis’ research brings out how policies are shaped not just in response to media coverage, but anticipating it. This is not because politicians believe that media “represent public opinion”. If politicians want a picture of “public opinion” they look to polling, or maybe their own far from representative experiences of meeting constituents. Out of Davis’ 40 interviewed MPs: “Only three believed news was an actual reflection of public opinion and looked to it for that purpose. Just under half, without prompting, described political coverage as overly ‘trivial’ and dominated by ‘personalities’ and the ‘dramatic’.”

How does this fit with the point that politicians’ paramount need is for approval from voters? Here are a few partial answers:

- First, politicians know that, while media don’t “reflect” current public opinion, they do have power to shape future public views. Most of all, they know that media have particular power over key target publics – as we will see in the next section.

- But above all, media have power to mobilise their audiences’ feelings around specific campaigns, which often target specific politicians. These include attack campaigns that can destroy a politician’s career – andpositive campaigns that can raise a politician’s profile.

- These strategic considerations aside, politicians are “news junkies” living in a media hothouse where all their thinking and feeling is framed by 24/7 media exposure. However much or little they’re aware of it, they are much more media creatures than most of us.

- Not only are politicians continually exposed to media stories and images, but they work and socialise alongside editors and journalists. They are colleagues and friends, they speak the same language, share the same values. Politicians actively consult journalists as they make policy, or even plan joint campaigns in advance – as in the infamous 2003 “asylum week” planned out by the Sun and the Blair government.In short, it makes sense to think of politicians and media as sharing a dense media-political ecosystem, where they feed off each other in spinning and weaving their stories.

6. Media and people: communication power

What about the rest of us? How much power do media have to shape our minds? There is considerable academic research tackling this issue from different perspectives.4Still, as Scott Blinder at the Migration Observatory observes, it is hard to pin down an “empirical” answer:

“It is extremely difficult to test for media impact on attitudes empirically, because it is virtually impossible to discern whether people learn their political viewpoints from the media sources they rely upon, or if conversely they choose to rely on media sources that reflect their pre-determined political viewpoint. It would seem likely that both processes occur, but research to disentangle one from the other faces formidable challenges and is likely to remain inconclusive.”

Our starting point is that people do not form their attitudes in isolation. Rather, our views are shaped throughout our lives in continuing interaction and communication with many others. For example, I may have personally experienced being turned down for a job, being on a housing waiting list, seeing my neighbourhood change. But also, I have talked about these experiences with friends, family, neighbours, colleagues, and heard their experiences, and these conversations shape how I understand what has happened. They give me new information, and they help me grasp contexts or “frames” that fit events into patterns, making them exemplars of familiar narratives.

All of us are continually receiving ideas from many others, and in the process our own views are continually being influenced and re-shaped. At the same time, we are all transmitting our ideas to others, and helping influence their views. But, clearly, some people and institutions have much greater power to direct these flows of ideas.

We can use the term “the media” as a shorthand to mean: organisations with particular access to major communication channels – and so with concentrated power to spread ideas and influence people.

To be clear, big media are certainly not the only sources of our views. But in a landscape where a few big players dominate major communication channels, this has important effects on our “ecologies of ideas”. We can then ask a few questions:

- just what reach do big media have?

- what ideas do big media spread?

- and why: what agendas or projects drive them?

6.1 media reach

Another 2011 Ipsos MORI survey, cited in the Perceptions and Reality report, asked: “which two sources would you say provides you personally with most of your information about immigration and asylum in Britain?” These were the answers given:

- News programmes on TV or radio: 55%

- National newspapers: 44% (tabloids 20%, broadsheets 18%)

- TV documentaries: 23%

- Personal Experience: 16%

- Internet: 10%

- Radio programmes: 9%

- Word of mouth: 9%

- Local newspapers: 8%

- Friend’s and/or relative’s experience: 7%

Without putting too much weight on this survey, it gives an indication of the importance many people themselves ascribe to the media in their thinking about immigration.

media segments

However, again, we need to see clearly that there is no one “public” in relation to the media, but many different people, reached by different media outlets, in different ways.

As the Ipsos MORI survey indicates, television is still extremely powerful. Although if the survey were carried out now, we could expect a stronger role for online media. According to more recent Yougov / Oxford University sampling, UK use of online news sites overtook TV for the first time in 2016.

Both TV and internet are much widely accessed than newspapers: over 70% of people said they had read news online in the last week, and a similar figure had watched TV news, but less than 40% had read a newspaper. On the other hand, newspapers are often considered to have particular influence in the self-referential media “debate” – what some academics call “intermedia agenda setting”. TV programmes are dedicated to “what the papers say”, and broadcast news often takes the lead from the morning papers. The press, and above all the most influential newspaper commentators, may play an agenda-setting role for the media overall.

There are marked generational differences in media reception. E.g., 84% of people aged 24 and under said online news and social media is their main source, with only 9% for TV. But 54% of people over 55 put TV first, and 15% of this age group relied most on newspapers. This is, of course, particularly relevant for our “target publics” – older white people with immigration anxiety.

Indeed, to go back to the main Ipsos MORI study we discussed in Section 2, here is one interesting fact: people who said they saw immigration as a problem “nationally but not locally” were particularly likely to be newspaper readers. 51% of this group said they read newspapers – as opposed to 41% of those who saw a “national and local” problem, and 43% of those who didn’t see immigration as a problem. And 16% of them read “mid-market” newspapers – i.e., The Daily Mail and Daily Express – as opposed to 9% and 6% in the other two groups.

6.2 immigration stories

There is considerable research on how media cover immigration. We will review a few highlights from four notable studies of UK media coverage:

- “What’s The Story?” Article 19’s study of the original asylum scare in 1999-2001 which led to the closing of the Red Cross refugee centre in Sangatte, near Calais.

- Bad News for Refugees by researchers from the Glasgow Media Group, which includes case studies of coverage during May 2006 and June 2011.

- “Press Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Crisis in the EU” a UNHCR commissioned study by Cardiff School of Journalism, which analyses reports from 2014-15 in five countries: UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden.

- “A Decade of Immigration in the British Press” by David Allen from Oxford University’s Migration Observatory, which studies press coverage over 2006-15.

All of these are essentially “content analyses”. They categorise and analyse the use of language, key words, different sources, narrative patterns, “frames”, and other elements. Most focus on newspaper reports – perhaps largely because they are particularly easy to search and categorise, but Bad News and UNHCR also look at TV reporting.

To start with the obvious point, the UNHCR study notes that: “coverage in the United Kingdom was the most negative, and the most polarised. Amongst those countries surveyed, Britain’s right-wing media was uniquely aggressive in its campaigns against refugees and migrants.”