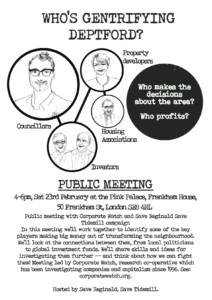

Who’s gentrifying Deptford? Identifying the profiteers, making strategies

[responsivevoice_button]

On Saturday 23 February Corporate Watch ran a meeting called “Who’s gentrifying Deptford?”, hosted by the Save Reginald Save Tidemill campaign. The meeting was packed out – 50 or so people squeezed into the Frankham Street “Pink Palace”, or listened outside through the open doorway. People came from estates facing demolition and development in Deptford and New Cross, from other parts of Lewisham, and from as far away as Brent.

Our aim for the meeting was to think through how gentrification works in a neighbourhood like Deptford and so help people develop strategies to fight it effectively. We started by flagging up two big questions: Who decides? And who profits?

Click here for a working list of 15 current development schemes in Deptford.

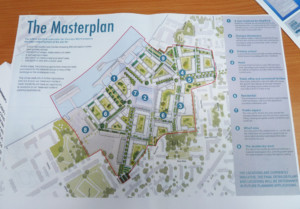

Picture: It often starts with a “Masterplan”, here for the Convoys Wharf development in north Deptford.

Who Decides?

It’s often very clear who doesn’t decide. In the Tidemill development, for example, the residents of Reginald House strongly oppose demolition of their homes but have been refused any say in the matter. More generally, most people living in gentrifying neighbourhoods have very little control over the changes taking place.

So who does cook up gentrification projects? The local council is often the first suspect. People at the meeting recalled how the Tidemill development started with council officers drawing up a “Masterplan” for the area, working with corporate consultants and other “experts”. They made a show of consulting local people through public meetings with “patronising” architects and PR wonks.

Behind the scenes, actual decisions are made in closed meetings between council executives, senior councillors – and property developers. At best, residents are allowed a say on small details, or get to haggle over a few dozen “affordable” flats.

The typical outcome? Developers get approval to cram yet more luxury flats and hipster markets into the area; working class residents are told they should be grateful for even a small number of so-called “affordable” homes. In Deptford and New Cross, over 5,000 new homes are currently being planned in what is already the densest part of Lewisham. Just a tiny handful of these will be for “social rent”.

Picture: Lewisham mayor Damien Egan with fans.

Meet the investors

So the most obvious decision-makers are council bosses – both elected councillors and professional officers – and the property developers they work hand in glove with. But there is another, deeper, level of power behind these. The property development companies are funded by – and ultimately answerable to – investors who make big profits out of sky-high property prices.

In the meeting, we looked at some of the main investors behind developments in Deptford. There are billionaires like Li Ka Shing, whose Hong Kong based family empire is behind the enormous 3,500 home development at Convoys Wharf – the old Royal Dockyard and now London’s biggest empty building site. There are massive global investment funds like BlackRock – which owns chunks of Lendlease, Grainger, and quite probably other development companies active in the area.

There are also specialist private equity investors like M3 Capital and Oaktree – one of the infamous “vulture funds” known for buying up debts of countries like Greece, but also behind the Anthology company which owns the Deptford Foundry skyscraper. And smaller figures like businessmen Tom Mulligan and James Gant, who own Bluecroft, the company developing No 1 Creekside.

Click here for an in depth look at these investors.

All for charity?

But what about the line, pushed by Lewisham councillors, that schemes like Tidemill are different, because the developers involved are “non profit” housing associations like Peabody?

As we have previously reported, the truth is that Peabody is “non profit” only in a technical sense. Nowadays only one third of its new buildings are for “social rent”, with most of its effort going into building homes for sale and rent at market levels. It’s true that it doesn’t have “shareholders” who get a share of profits (in payments called dividends). But it does have a chief executive on £300,000 a year, and 50 other managers earning over £100,000.

And it certainly does have powerful investors. Instead of selling shares, Peabody and other big housing associations sell corporate bonds. Many bond investors are likely to be just the same big investment funds, the likes of BlackRock, who invest in other developers. But as the bond market is much less regulated than the share market, it’s much harder to find out who they are.

Picture: Bob Kerslake, Peabody chairman

Who profits?

So the second big question we looked at was: who profits, who gains, from these schemes?

Obviously, the investors who buy shares or bonds in the development companies get paid dividends or interest in return for their investments. And also the managers who rake in often huge salaries and bonuses. But we also looked at other kinds of “gains” beyond the obviously financial. For example, what motivates councillors to push development schemes?

Certainly, there can be financial benefits. For example, it’s well known how some politicians like Southwark’s council leader Peter John collect dozens of reported gifts from developers like Lendlease.

But another issue is probably much bigger than obvious gifts: the culture of “revolving doors” between councils and developers. Councillors and council managers spend a lot of time meeting and networking with developers. Later, many get jobs as well-paid corporate executives or “consultants”. So in the long run, they certainly profit from their connections in the development world. When there’s a few years of delay between service rendered and payment returned, it’s somehow no longer considered “corruption”.

Still, not all cuddling up with developers is driven by money. For example, many ambitious politicians use council seats as part of their climb up the greasy ladder towards parliament. They may use schemes to build a reputation for “getting things done” and for being friendly to business. These characters may be chasing power and status rather than just financial gain.

Finally, many councillors and managers no doubt genuinely believe they are doing the best they can. They have swallowed whole the line that there is “no alternative” to this kind of development. And it’s much easier to maintain this story because they don’t directly feel the pain of gentrification themselves. Its notable that the councillors pushing Tidemill are all home-owners on comfortable salaries. None of them face having their own homes demolished or being priced out of their local shops. As people said at the meeting, they are part of the “political class” – which is tightly interconnected with the business class, and shares similar values and assumptions.

Picture: Councillor Joe Dromey, “red prince” of New Cross

Identifying the decision-makers

In the second part of the meeting, we zoomed in on a concrete example. We made a “mind map” of the key players making decisions about, and making money from, the Tidemill scheme.

At the top of most people’s list were two: Peabody Homes, and Lewisham Council – including particular councillors and senior officials who have been active in driving the scheme. Another “for profit” developer, Sherrygreen Homes, is also involved alongside Peabody. Although Lewisham councillors have recently been downplaying the role of Sherrygreen, it is believed to still be very much part of the scheme. We also discussed the investors funding Peabody and Sherrygreen.

But as well as the council and its “developer partner”, a host of other players are also necessary to make the scheme happen. These include the building contractor, Mulalley, and the architects Pollard Thomas Evans (buildings) and BDP (landscape).

Other contractors include consultancies and demolition companies. In recent months, a lot of focus has been on two contractors playing a vital role at the current early stage: security guards, and tree surgeons. The council paid well over £1 million to its original security contractor, County Enforcement, who we profiled in November.

After Corporate Watch exposed County’s union-busting history, councillor Paul Bell, Lewisham’s cabinet member for housing, promised to replace them with a different firm (while their anti-union history bothered him, he had nothing to say about their recent assaults at Tidemill). This appeared to finally happen on 18 February. The new security guards have been instructed to tell people that they are directly employed by the council. When asked, they refused to give their manager’s name, or to identify any contracting firm.

A tree surgeon firm called Artemis began cutting trees back in November 2018. After many people asked them to stop – at the site, and also by email and on social media – they pulled out of the contract after the first day. (At the time of writing in March 2019, Lewisham has been able to go ahead with tree cutting after bringing in another company from Gloucestershire.)

Picture: Larry Fink (right), CEO of BlackRock, with other big property investors.

Weak points

Fighting gentrification is a David and Goliath battle against the massed power of finance capital and politics. On the front line, that comes down to the armies of police and private security guards used to push through developments like Tidemill when people resist.

To have any chance of beating them, people may need to think strategically, and deploy cunning and creativity against their brute force. After identifying the gentrification players, we started to think about strategies: now we know who is doing this, how can we fight them? Does it make sense to target some players in particular? What actions might lead different ones to drop or pull out of the scheme? What “leverage” can campaigners find to influence them? What are their weak points?

For example, take BlackRock, which finances and profits from various Deptford developments. It is one of the world’s greatest financial empires, based in the US. What could the 50 odd campaigners sitting in the Deptford pink palace do to stop BlackRock stop gentrifying the neighbourhood? The likely answer: sweet nothing.

On the other hand, the Tidemill campaign had already had two small victories: getting County Security’s contract cancelled, and persuading Artemis Trees to pull out themselves.

There was no doubt in the room that Lewisham Council, too, has been feeling pressure from the campaign. Its “socialist” mask slips badly when it sends an army of security guards to destroy a community project and people’s homes, revealing the brutal arrogance of the careerists at the top. We also discussed how the campaign is linking up with Peabody tenants across London, who are increasingly challenging neglect and profiteering by their landlord.

We won’t go into more detail here on the strategic ideas discussed. We’ll just say there was a really strong positive energy in the room. The battle for Tidemill is still far from over. But also, it’s an example of impassioned resistance, and its spreading. On Saturday people from across Deptford, Lewisham, and beyond, were sharing ideas and strategising together about how to fight off new developments.

iPeople in the meeting raised the example of local New Cross councillor Joe Dromey, son of senior Labour politicians Harriet Harman and Jack Dromey. He has already tried once to be selected as MP candidate for Lewisham East, even despite an all female shortlist, and is widely expected to try again soon.