Who’s in control? A short guide to investigating corporate power

Download a pdf version of our new guide to investigating corporate ownership and control here. Company information accurate as of October 2024.

If you’re planning a campaign against a company, it’s helpful to know exactly who you’re up against. By understanding who makes the decisions, you’re better placed to devise a campaign strategy that really works.

Is the power behind the throne a well-known brand with a squeaky-clean image? Or someone with important political connections? Are they a patron of a homelessness charity? Knowing exactly who we’re up against allows us to develop strategies that force the company to pay attention, and better still, to act on our demands. Having the right info also opens up avenues for further research, for example looking into the correct company accounts, or investigating bosses’ other shareholdings.

It can be easy to assume that all important decisions are made by the smiling suits on the ‘About’ page of the company website, but this is by no means always the case. In this guide, we set out the fundamentals for groups looking to put names and addresses to faceless corporate foes.

THREE CENTRES OF POWER

A useful starting point is to understand the three main power bases in a medium-large sized business:

Executive Committee: These are usually the people that you’ll find on the company webpage: the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Managing Director, and so on. The executives not only earn the highest salaries but usually have benefit “packages” which include share dividends, giving them even more power. They’re responsible for the day-to-day management of the company, but not major strategic decisions (for example, whether to divest from fossil fuels). The executives are appointed by and answerable to the board of directors.

Board of Directors: The board has principal responsibility for the organisation’s strategic choices and policy decisions. It has the power to appoint the executive committee and set their salaries. It tends to be composed of a few members of the executive committee, alongside a handful of “independent” or “non-executive” directors (NEDs). Among NEDs, it’s not uncommon to find politicians and directors of other companies. The board is elected by the shareholders.

Shareholders: A company listed on a stock exchange (a ‘plc.’ in the UK) will usually have a large array of shareholders, including major banks, and omnipresent asset managers like BlackRock and Vanguard. Shares represent to a fraction of ownership in a company, and the number of shares held by a shareholder corresponds to their voting rights in major company decisions.

SHAREHOLDER POWER

Since shareholders have the power to appoint the directors, the largest among them hold significant sway in a company, as they can ‘out-vote’ smaller ones. A company or individual with over 50% shareholding (a ‘controlling interest’), will dominate policy discussions.

Shareholders can be both companies and individuals: for example, a company’s shareholders could include JP Morgan, and your neighbour whose day job is as a teacher. But the likelihood is that JP Morgan’s share – and therefore voting rights - will significantly outnumber your neighbour’s.

A private (usually, ‘Ltd.’) company will often have a far smaller number of shares and shareholders, with the latter often just the company bosses. This is the form commonly found among small businesses, however, these companies are by no means always small.

A ‘plc.’ on the other hand, stands for public limited company, which means that shares are generally sold to the public via stock exchanges. Public companies are required to disclose more information, which can be useful for research purposes. Like Ltd. companies, if the business goes bust, a shareholder’s financial risks are limited to the value of their shares. They are also largely protected from legal responsibility for corporate malpractice.

You’ll often find cases with a few people who fall under all three categories: people who are both directors and members of the executive committee, as well as major shareholders. These individuals therefore hold significant power.

However, in large companies, it is common to have complex chains of subsidiaries, holding companies, and shell companies. So, establishing where the power lies in these scenarios requires further digging.

Who owns the company?

In the case of UK companies, those that have a greater than 25% shareholding – directly or indirectly – are generally defined as ‘persons of significant control’, otherwise known as a ‘beneficial owner’. In the case of more than 50% voting shares, a shareholder clearly has a majority voice in a company and would be considered to have a ‘controlling interest’.

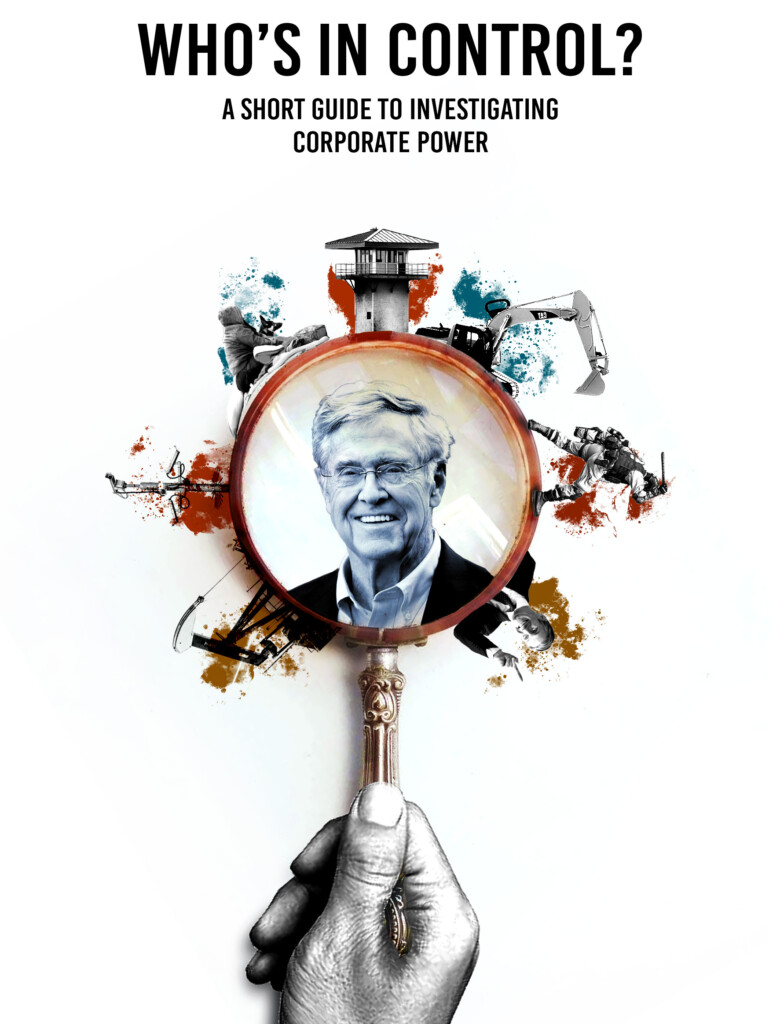

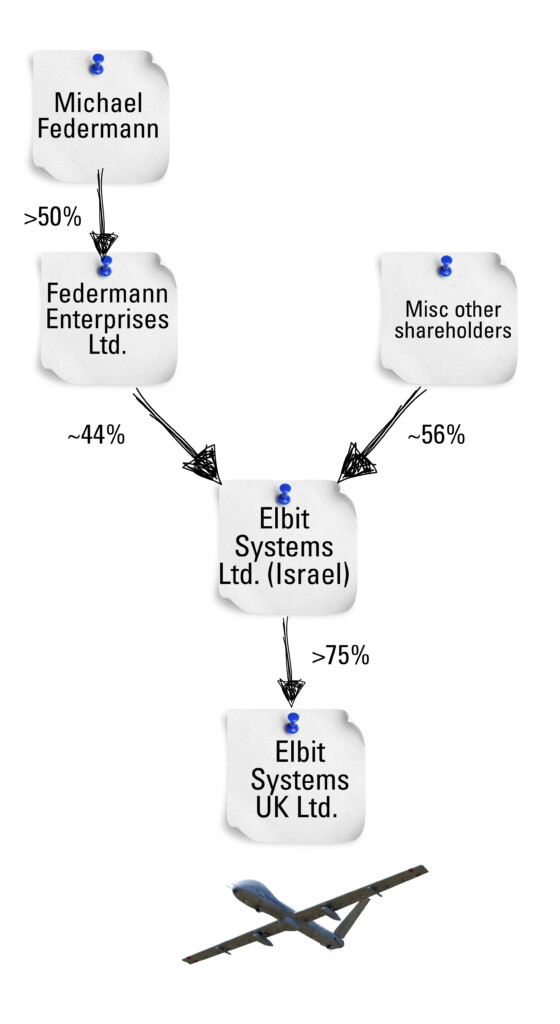

It’s important to be aware that this power can be exercised indirectly through subsidiaries, companies more than 50% owned (and therefore controlled) by another. Sometimes, the chain of ownership is relatively straightforward. For example, let’s say you’re organising against Elbit Systems UK Ltd., and you want to find out who owns it:

We can see that the Israeli company has more than 50% shareholding of the UK one, and therefore has a ‘controlling interest’. But with a bit more digging, you can see that the beneficial owner is Michael Federmann, as his firm is a person of significant control in Elbit’s parent company (in reality, his share of Federmann Enterprises is exercised through some additional companies, but we have simplified the chain for clarity):

We can see that the Israeli company has more than 50% shareholding of the UK one, and therefore has a ‘controlling interest’. But with a bit more digging, you can see that the beneficial owner is Michael Federmann, as his firm is a person of significant control in Elbit’s parent company (in reality, his share of Federmann Enterprises is exercised through some additional companies, but we have simplified the chain for clarity): Tracing beneficial ownership can sometimes be a complex task which requires thinking about the bigger picture. Consider this example, which shows the largest shareholders of each fictional company:

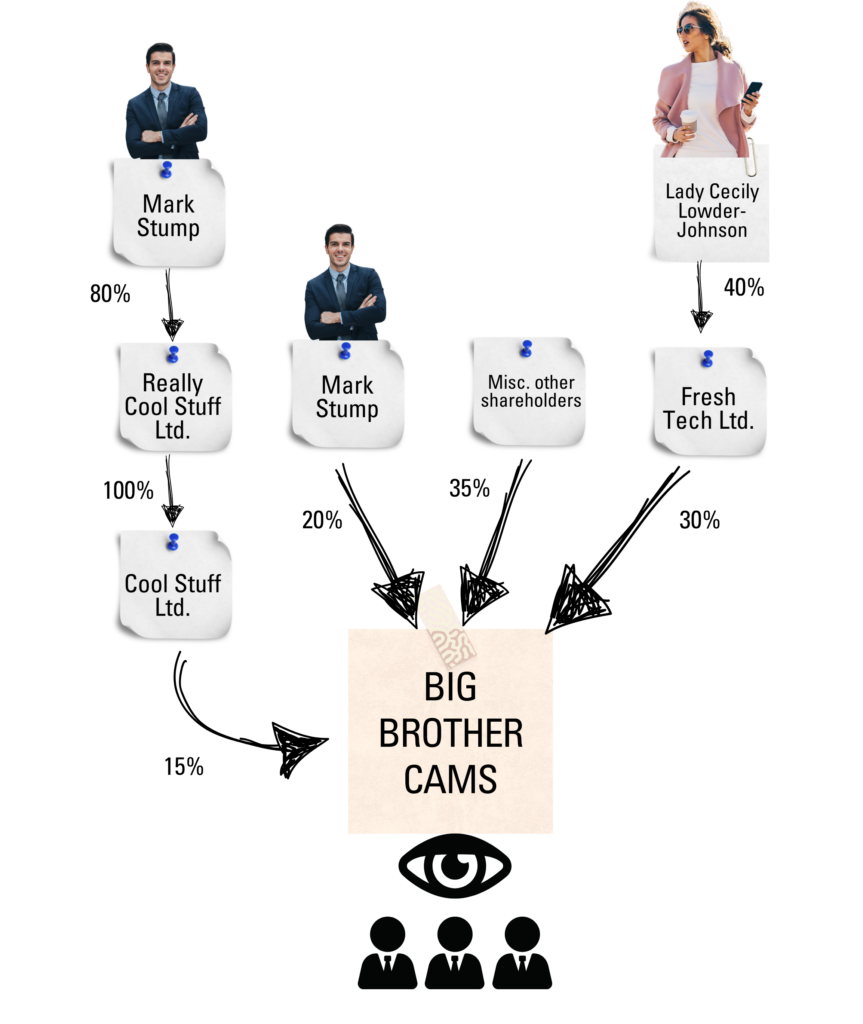

Tracing beneficial ownership can sometimes be a complex task which requires thinking about the bigger picture. Consider this example, which shows the largest shareholders of each fictional company: At first glance, it might look like FreshTech Ltd. controls Big Brother Cams. On closer inspection, you’ll see that Mark Stump not only has an outright stake of 20% in the company, but he has an indirect share via his ultimate controlling interest in Cool Stuff Ltd.; CoolStuff and Stump’s direct shareholding together outnumbers FreshTech’s.

At first glance, it might look like FreshTech Ltd. controls Big Brother Cams. On closer inspection, you’ll see that Mark Stump not only has an outright stake of 20% in the company, but he has an indirect share via his ultimate controlling interest in Cool Stuff Ltd.; CoolStuff and Stump’s direct shareholding together outnumbers FreshTech’s.

Therefore, we can say that Mark Stump is a person of significant control in Big Brother cams, and holds sway in company decisions.

It’s also important to note that when it comes to large companies, a 25% shareholding can represent an enormous amount of money. So even an investor with a 2% holding in the company may be making significant sums in dividends (payouts to shareholders associated with company profits), even if they do not hold much influence.

Another reason it’s useful to understand ownership is because a company that markets itself as ethical may have been sold to a multinational with very different environmental and human rights standards. Take a look at this ownership chart of some well-known ‘green’ brands. How might this information influence a campaign strategy against the subsidiary?

JARGON BUSTER

As you track the chains of ownership and control, at some point you’ll come across the following types of company:

Subsidiaries: The general term for a company controlled by another (parent) company. Large companies usually have many subsidiaries, which with their parent are collectively referred to as the ‘corporate group’. Subsidiaries are often set up with the aim of operating a business in another country, or to minimise financial and legal risk and reduce tax payments by moving assets around the corporate group.

Wholly-owned company: If a person or company owns 100% of the shares, it means it’s ‘wholly-owned’ by that shareholder, and they have exclusive decision-making power.

Holding company: A form of parent company that doesn’t produce or sell any goods or services itself, and has been set up purely to hold shares/stock in its subsidiaries. Aside from potential tax perks, one benefit of this arrangement is to avoid liability: a group’s assets in the hands of a holding company may be protected if a subsidiary goes under, or if the subsidiary is sued. This has historically presented a problem for groups seeking accountability for the impact of multinationals in the Global South – from sweatshop labour, to environmental devastation.

Shell company: A business that exists purely to hold assets rather than to carry out any business. Shell companies are usually set up to dodge taxes and regulations, and may be registered in tax havens like the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg or Cyprus, making it challenging to identify the beneficial owners.

Tracing ownership: a step-by-step guide

Step 1: Make sure you have the correct company name

It might sound obvious, but there are over 4 million companies registered in the UK. It’s important to understand the difference between a brand name (eg. Innocent Smoothie), and its legal name (Innocent Limited). A single brand might also have dozens of legal entities to its name.

So the first step is to make sure you’re looking at the correct legal entity: Are you looking for CoolStuff Ltd., or CoolStuff plc.? You can usually confirm a company’s legal name quickly by looking at the small print on its website: it should be included in the footer, or in legal notices such as its cookies policy or privacy notice.

Occasionally, this information is not available, so you may need to find ways to get your hands on legal documents (such as court cases involving the company), where the full legal title is stated. If this is not possible, it’s going to be a process of elimination involving various elements, including a search on Companies House using the registered address, and cross-referencing with databases (more on this later).

2. Run a search in Companies House

Once you have the legal name you’re looking for, you can run it through Companies House. Companies House is the official register of UK companies and includes the UK branches of foreign firms as well as the UK parents of foreign subsidiaries. You can run a search for a company here. If the business you’re looking for isn’t based in the UK, you’ll need to use an overseas register.

Overseas registries vary significantly in the degree of information available, and many charge to see search results. A free alternative is OpenCorporates, a database which draws on information from over 140 registries globally and can provide useful initial info for your search. A similar database is Open Ownership: after running a company search and selecting the correct entity, if you click the ‘view as graph’ tab, it’ll show you a visual map of the companies in the group. This includes subsidiaries of the business you’re looking at (which is less easy to find through Companies House). In the earlier case of Elbit, you’ll be able to see at a glance that the UK branch has subsidiaries of its own, which presents other potential focal points for campaigning.

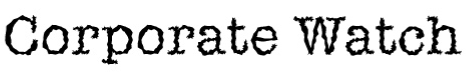

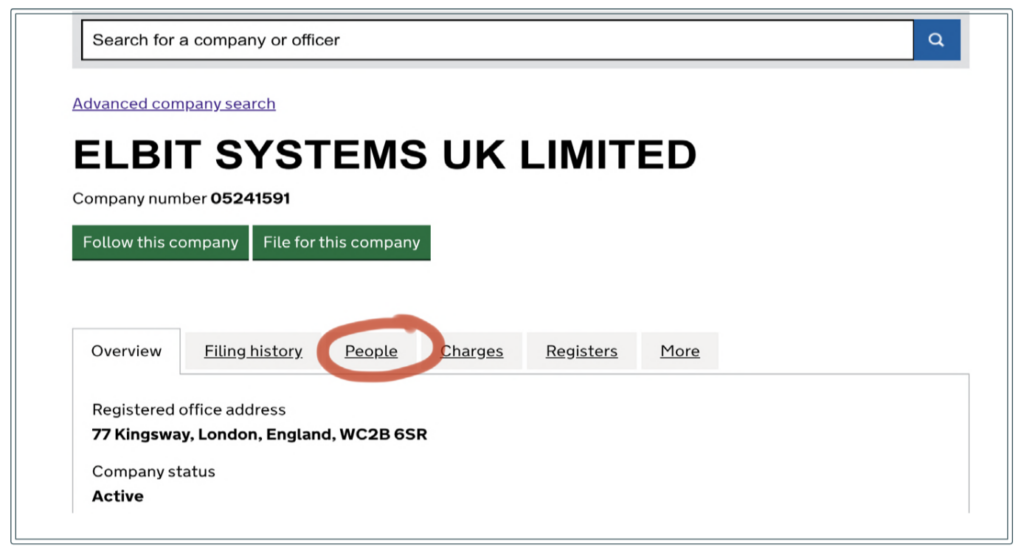

Back to Companies House. Once you click on the correct company, you’ll see a series of tabs. Click the ‘people’ one – this will give you the former and current directors of the business:

Click on ‘persons with significant control’ to reveal the dominant shareholder as well as the approximate percentage of shares they hold (described as the ‘nature of control’):

Click on ‘persons with significant control’ to reveal the dominant shareholder as well as the approximate percentage of shares they hold (described as the ‘nature of control’):

It’s rare to find the page showing percentage of shares when you first look, more often than not, you’ll find the name of another company, or person, so you’ll need to follow the stages set out below. If there are no persons of significant control, it means exactly that – there’s no single legal entity (an individual or company) that holds major sway over the business.

If the results reveal a foreign company, you’ll need to follow up using an overseas registry, OpenCorporates, Open Ownership, or global subscription database if you have access to one (more below).

3. Follow the chain of ownership

Sometimes, one search will produce the beneficial owner’s name, and it’ll end there. This is often the case with very small companies. However, for larger businesses, you’ll have to start following the chain of ownership up to potentially a dozen levels or more.

- To do so, take the name of the individual or company with significant control, and paste it again in the search bar of Companies House.

- Click ‘people’> ‘persons of significant control’, and run another search.

- Do this multiple times until you can go no further: your search might take you to the Emirate of Abu Dhabi; a Guernsey-based shell company; or some bloke in Essex.

Once you start seeing ridiculous names like Bidco, Midco and Topco; Bidco 2, Topco 2 etc., you haven’t gone mad, you’ve merely entered the murky world of private equity firms.

Now have a go with this example: Look up Goram Homes Ltd., a Bristol developer involved in evicting Travellers. What’s the power behind this company?

The limitations of Companies House

The UK has one of the world’s most accessible company registries, and the owners of many businesses can be found if you know how to use it. However, complex structures and offshore parents can make investigating certain companies particularly difficult. In such cases, subscription databases such as Orbis or Capital IQ – available via some universities – and cross-referencing different sources, can help fill the gaps. These databases contain detailed data of shareholders of listed companies, for example.

If you think you’ve hit a brick wall, feel free to get in touch with us and we will see if we can get any further. Investigating offshore shell companies is a very niche and complex area, which organisations such as the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICRJ) specialise in.

Palestine Action occupation of an Elbit subsidiary’s Tamworth factory. The site was shut down for good after a sustained campaign of direct action.