Will the Supreme Court give police the ‘right’ to mass surveillance?

[responsivevoice_button]

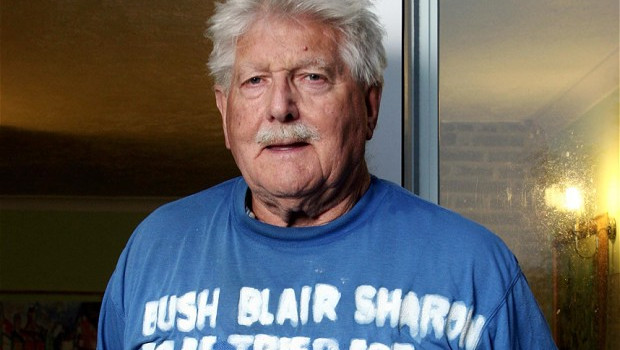

Pictured above – John Catt, who took a case against the police for storing data on his attendance at protests

The Metropolitan Police and the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), with the backing of the Secretary of State, have been fighting a case in the Supreme Court, defending their ‘right’ to store data on protesters. They are appealing against a 2013 judgement, which said that they were obliged to destroy data about an anti-war protester called John Catt. The ruling has implications for the police’s right to store data on everyone. The court has now heard legal arguments and a judgement is expected soon.

John Catt had been put under surveillance while attending demonstrations and public meetings against Brighton arms dealers, EDO MBM (Exelis). John made a subject access request under the Data Protection Act, which showed that the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU) had stored details of his appearance, his vehicle and the demonstrations he had attended (the NPOIU is now called the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit)

The campaign against EDO MBM has lasted since 2004. A diverse range of tactics have been used against the company ranging from regular noisy demonstrations outside the factory, mass demonstrations in Brighton, acts of night-time sabotage and blockades of the road where the factory is situated. In 2009, during the murderous Israeli assault on the Gaza strip known as Operation Cast Lead, six people broke into the factory and caused hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of damage to the production line, stopping the factory from producing weapons which could be used against people in Gaza.

The campaign as a whole was costing the factory and the police money. The constant demonstrations had spooked the company and, in 2006, they had embarked on a costly and ultimately fruitless legal case in the High Court, aimed at creating a protest free zone around their premises (to find out more see SchNEWS’ On the Verge). Campaigners defended themselves in court and won, the factory was left with a legal bill to the tune of a million dollars, some of which they had to pay to the protesters themselves. The company was forced to erect a new fence around the premises, employ security guards with dogs and heighten security measures.

The police, whose job is to protect private business from public anger, were keen to stamp out the campaign. At the time when John was put under surveillance, Sussex Police had no proof of who was responsible for the acts of sabotage against the factory. Their only option was to target the visible face of the campaign, the weekly protests against the factory. John, then in his early eighties, was a regular presence at the demonstrations, often sitting and sketching the lines of cops, police camera units and hired security guards that assembled. The police repeatedly noted down information about him, who he was with and his car number plate. Later, when he was driving through London, his car was flagged by the police’s Automatic Number Plate Recognition System (ANPR) as “Of interest to Public Order Unit, Sussex police” and he was pulled over. He was targeted for arrest on two occasions and treated violently by police in the process. Charges were placed against him, which were dropped months down the line, and he was given bail conditions restricting his right to protest. John and his daughter were photographed, followed and harassed by police evidence gatherers at the demonstrations he attended.

By this time the police had dubbed campaigners against EDO as ‘domestic extremists’, a term that was usually used to describe the animal rights movement but was beginning to be bandied around as a catch all term for campaigns that used direct action against the powerful; from anti-g8 activists to climate campaigners. They had been vilified in the right wing press and the police campaign against them was in full swing.

Of course the harassment experienced by John and his daughter is by no means unique. It will be a familiar story to anyone involved in effective campaigns against corporate power. Ruling in favour of John in 2013, Lord Justice Moore-Bick commented that “Having seen copies of various reports in which Mr Catt is mentioned and the information provided in response to his subject access request, we are left with the clear impression that police officers who attend protests organised by Smash EDO for the purpose of gathering intelligence record the names of any persons whom they can identify, regardless of the particular nature of their participation.” Moore-Bick considered that the retention of John’s data breached his right to a private life.

It is interesting to look at the targeting of John by Sussex Police in the light of the political trials of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) activists. Animal rights activists have been waging a militant campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences, one of the world’s largest animal testing laboratories for over fifteen years. The resistance has included acts of sabotage and arson. Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty was a public campaign aimed at promoting lawful acts of protest against HLS, its customers, investors and suppliers. The police and government acted to silence dissent against the company and new laws were created (for example sections 144 and 145 of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act) to protect the pharmaceutical industry against the animal rights movement. As was the case with Smash EDO in Brighton, the police acted to criminalise those publicly identified with SHAC, whether or not what they were doing was against the law. In 2009 and 2014, lengthy sentences were doled out to campaigners for conspiracy to blackmail. The evidence against many of them was simply that they were guilty of being involved in a protest campaign against the company at the same time as illegal acts of direct action were going on. Similarly, Sean Kirtley was jailed for 4 and a half years under SOCPA in 2008 for simply running a website against Sequani, another contract testing laboratory, and attending demonstrations outside the premises. He successfully appealed his conviction in 2009.

During last week’s three day hearing at the Supreme Court, lawyers for the police and Theresa May made the following arguments appealing the ruling that they must destroy John’s data (as summarised here by NETPOL):

– Protesters have ‘no reasonable expectation of privacy’ when they take part in public demonstrations;

– In taking notes and photographs of demonstrations where there may be criminality or disorder, the police are doing only what they are expected to do.

– There is no support in case law for the idea that data retention alone could be an interference with Article 8 rights to privacy.

– Individuals are entitled to control over their personal information – but people voluntarily give up some of those rights when they take part in public demonstrations.

– That even if the retention of data was an interference with private life, this was justified by the need for the police to retain whatever data they consider necessary for police purposes.

John’s lawyers disputed the above arguments and argued that, despite police statements to the contrary, John had been consistently targeted as a ‘known individual’ and had been subjected to sustained and systematic surveillance. This systematic collection and retention of personal information amounted to an interference with his right to a private life.

Beyond the high-flown legalistic language, what the police are really fighting for at the Supreme Court, backed up by the Secretary of State, is the right to continue to criminalise people voicing dissent against the powerful, even if there is no proof that they have been involved in illegal acts. Because John Catt was involved in public acts of protest at a time when other people were carrying out illegal acts of direct action he was deemed a subject fit for police surveillance and harassment, even though there was no suggestion of any suspicion that he ever intended to break the law.

The case is reminiscent of cases in the US where the state is fighting tooth and nail in the courts for the right to harvest people’s internet and phone records. For example, last year a judge in the US ordered the government to stop collecting data on two people who had brought a private case against data gathering. The US government is currently appealing the case.

Of course, the police don’t necessarily respect a legal framework in order to carry out surveillance. Undercover police officers were planted in protest movements for years without any legal basis. The wholesale state surveillance of the internet had existed for years, long before the Snowden revelations proved the extent to which it existed and people had a new foothold to challenge it in court. What the case today, and other cases such as the civil claim being brought against the Metropolitan Police by people whose lives have been affected by undercover officers, are about is whether the state and police have a ‘right’ to carry out mass spying and surveillance with the blessings of the court system.

To read more about the campaign against EDO MBM (Exelis) see www.smashedo.org.uk

To read a detailed run down about the police’s appeal against the judgement ordering them to destroy data held on John Catt see these reports from Netpol: day one, day two, day three

To read more about how the state acts illegally when the law does not meet its need for repression and control see this chapter of Corporate Watch’s recent book, Managing Democracy, Managing Dissent